In the summer of 2008, Stephen McLaren was living in Bethnal Green, East London, and occasionally wandering westwards into the financial heartland of the City of London to take photographs. By this time, the Federal Reserve (the central bank of the USA) had already been

scrambling for months to save a crippled American housing market, and the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September was looming. In the introduction to his 2018 photo book, The Crash, McLaren looks back on the period with a calm before the storm-type prescience: “Whispers of an impending financial meltdown carry in the wind,” he writes, almost poetically.

The reality was more of a hurricane. But instead of venturing further afield to document the austerity, homelessness and sharp rise in payday loan and food bank usage that the 2008 financial crisis wrought, McLaren remained at the epicentre for a further four years, tracing the effects of the recession on London’s most powerful businesspeople. They too faced redundancy, uncertainty and professional meltdown, but the story McLaren tells in The Crash is one imbued with disdain: it’s a portrait of the City of London as a place of excess, greed and selfishness—stubbornly resistant to self-examination and destined to repeat the mistakes of the past.

“The Crash is unforgiving and pessimistic; this is a world to be dismantled, not reformed”

Economically, we are in a similar moment today. But the iconography of McLaren’s London—the expensive suits on awkward, exhausted bodies, the rooftop drinks receptions, cigars lit at lunchtime outside dark wooded city pubs—has now all but disappeared. In 2020, newspaper front pages bear the same plummeting graphs as in 2008 (garish front pages of the Evening Standard are a recurrent motif in the book), but the streets and offices are now empty in the wake of coronavirus.

As well as providing a historical snapshot, McLaren is concerned with the circular nature of the attitudes which led to the crash, of what he calls “a delinquent mindset at the heart of London’s financial industry.” If the same psychology is motivating the current crisis, whereby those in power value commerce over the health and welfare of their citizens, then McLaren’s exposition of this powerful elite suddenly feels like a valuable relic. It offers a reminder of governing forces which are now even less visible than before.

The Crash is split into six sections, which each focus on a particular moment or aspect of life in the City from 2008-2012. Following the opening chapter, The City in Meltdown, is a series of images showcasing the ceremonial aspects of the City of London corporation, the oldest continuous democratic commune in the world. McLaren captures robed men parading the streets around the Guildhall while judges stand lined up on a fountain. In one shot, a gold mace is laid ornamentally on the backseat of a Rolls Royce; turning the page reveals a man covering himself in a sleeping bag in front of the Bank of England’s facade, also the site of the 2009 G20 conference protests shown later in the book.

In another photograph, three suited men walk past an empty storefront, with dismembered naked mannequins stacked horizontally in the window. McLaren’s skill is to capture the natural contrasts of life in the City, not to choreograph for shock factor. One shot of a man carrying a crate of champagne, McLaren writes, was taken on the day in March 2012 that then-chancellor George Osborne announced he would lower the top rate of tax. Women and people of colour barely feature in these streets. The place is laden with symbolism, vulgarity and incoherence; McLaren’s is a project of assembly and arrangement, allowing the book’s impact to extend far beyond just the events of 2008.

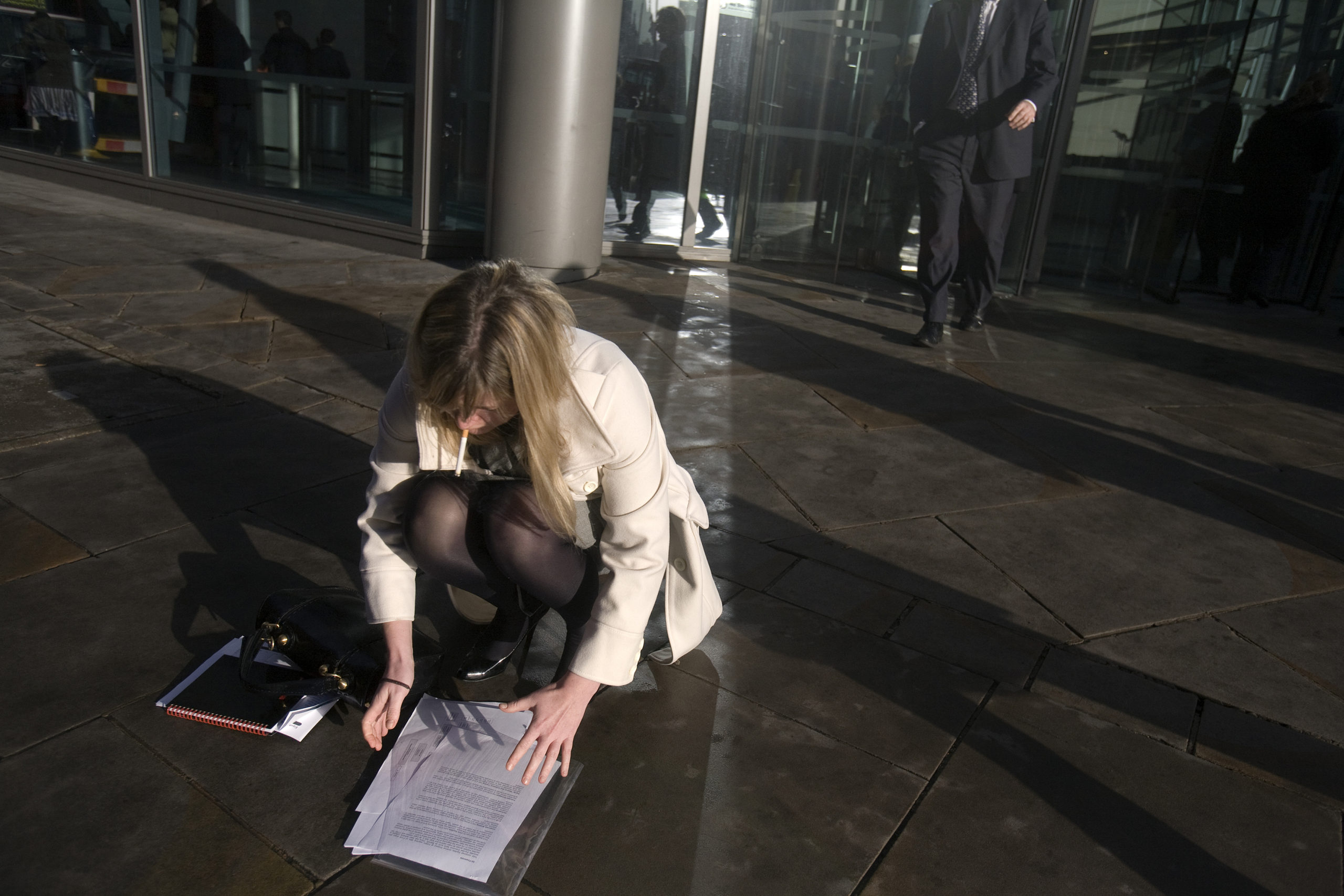

‘Leaving RBS HQ a woman fumbles Fourth Quarter earnings reports’, from The Crash (Hoxton Mini Press, 2018). Courtesy of the artist

“The detritus of overwork is everywhere, though sympathy is in short supply”

Death in the City is the most affronting section; the preface emphasises that 34 people chose to end their lives in the City of London between 2009 and 2014. What follows is a selection of men looking ominously upwards; hazard tape is stretched across the pavement as workers stream past, demarcating a newly initiated site of loss. Front pages chronicle detail head-on where the images can only hint at their edges: “City Woman Dies in Horror Plunge”.

The Crash’s subjects look increasingly dishevelled as the book’s trajectory goes on: water bottles, swipe cards, cigars and cigarettes are the chosen objects clasped in mouths as men maraud around the streets. The detritus of overwork is everywhere, though sympathy is in short supply: Starbucks espresso cups, Marlboro Gold cigarette packs and discarded chewing gum feature heavily throughout. McLaren’s lasting message, however, is a warning of recurrence and lessons unlearnt.

The Crash is unforgiving and pessimistic; this is a world to be dismantled, not reformed. One of the book’s closing shots shows a suited man sunbathing on a small stretch of beach just west of Southwark bridge. His yellow tie snakes over his torso towards the ground; behind him, the Shard is being constructed against the pale blue sky. It is a shot of relative serenity, but one tarnished with alienation in the context of what has gone before. An inscription in the book asks the question, “How has East London changed since the crash?” McLaren’s reply is bombastic—a rallying carry for our times: “The financial barbarians are at the gates of East London and only community spirit can turn them back.”