Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

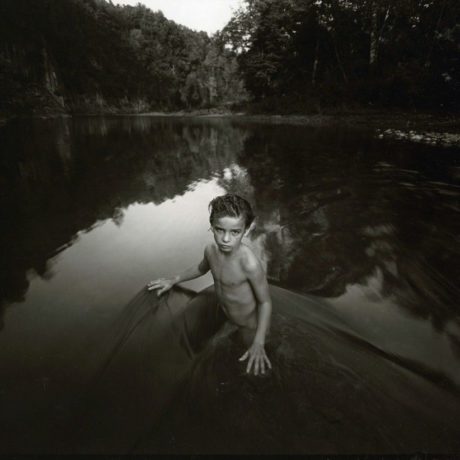

Out today on Artsy is Matt Williams on Sally Mann’s Immediate Family.

I’ve always found it difficult to stay long in one place, and have moved frequently in my life. Last month, I came across a quote from Alex Niven’s recently released book New Model Island. It explains, with great accuracy, the difference in experiences between those hailing from Northern corners of the UK and those who come from London and the South East. Niven writes that Northerners are more likely to lead lives “full of migration from place to place” and that “they will have to find a way of dealing with the profound emotional and practical difficulties that come with being uprooted from successive locales”.

As a woman from Yorkshire, raised in Leeds, who has lived in several cities around the world—notably London and, more recently, Berlin—Niven’s observation struck a chord with my own relentless reality. It triggered a sudden jolt of awareness in my mind, and I found myself reflecting on the powerful role that art has played in my life amidst my many relocations. In particular, I remembered how one artist aided me when seeking my own personal peace with what will likely

be my lifelong nomadism.

Barbara Hepworth, born in Wakefield in 1903, is one of Yorkshire’s most culturally significant figures. Her radical, tender work redefined what it meant to be a sculptor. She rejected and reshaped the processes and principles that came before her, and even acted as a friendly rival for fellow icon of twentieth-century art history Henry Moore. To my eyes, her pioneering abstraction of the human form far surpassed where even Moore dared to reach.

For many, Hepworth will always be most closely associated with St Ives, where she lived and worked from 1939 until her tragic death by an accidental fire at her home. To me, Hepworth is Yorkshire. She represents home, familiarity and the embodiment of what it means to be a proud Northerner. As someone who finds relocation thrust upon them as an occupational necessity, that notion of home has never felt more important.

“The scale and majesty of the piece is often lost amidst the lofty bustle and clamour of the capital’s busiest shopping street”

When I first moved to London, looking for my place in the creative industry, I found myself working just behind Oxford Circus. My first role was as a social media intern at a well-known design brand; I expected to remain with the company for six months but ended up staying almost two years. It was like existing within a postcard sent from a fantasy world that, back in my bedroom in Leeds, I never dreamed possible.

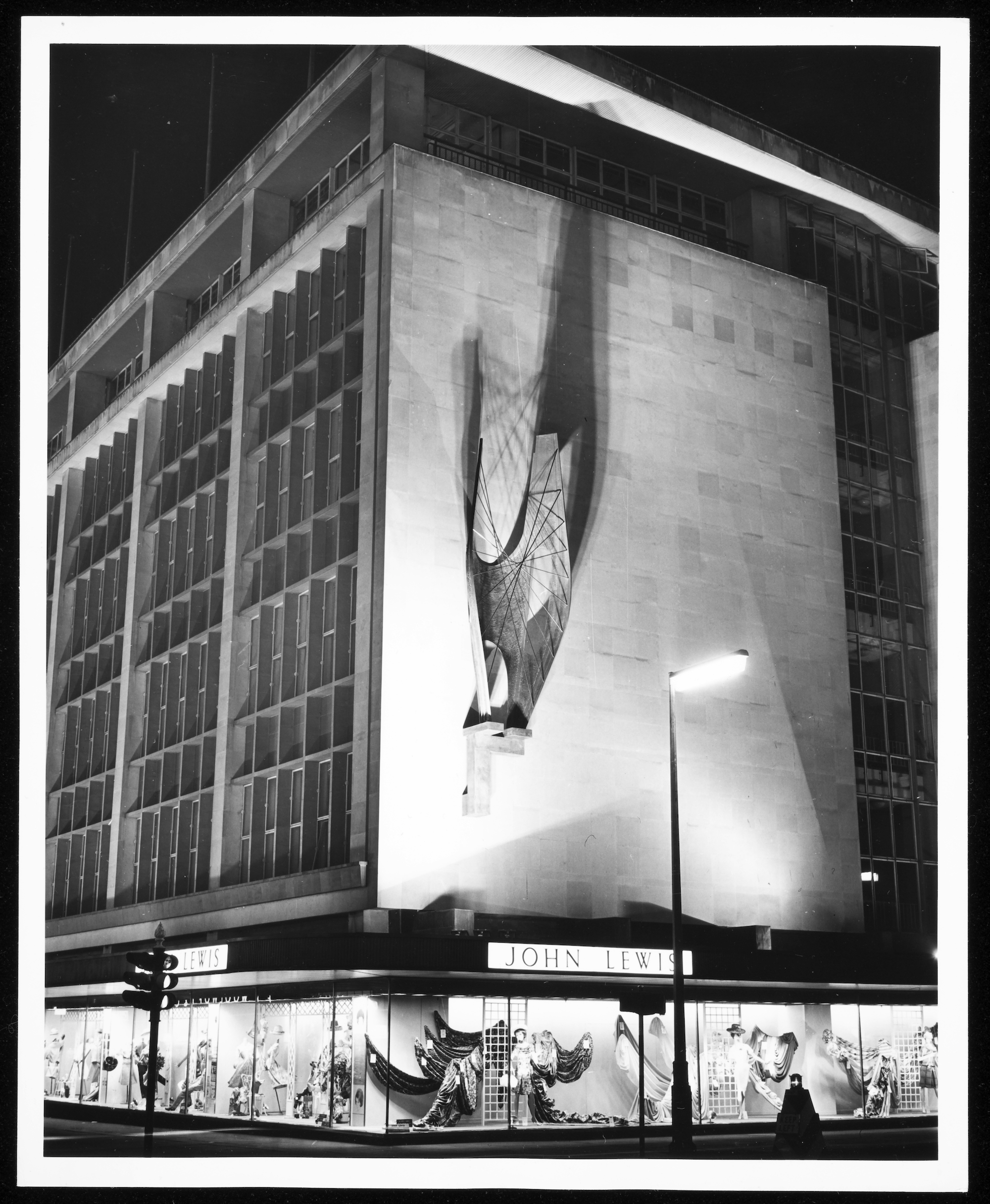

My first serious boyfriend worked in nearby Soho and we would relish the short walk between the two, hand-in-hand, ogling the bright lights of the capital at night. It was on one of these walks that I began to observe a sculpture, mounted high-up on the east side of the flagship John Lewis department store—that beacon of the British middle classes. The sculpture was Hepworth’s 1963 Winged Figure. While the scale and majesty of the piece is often lost amidst the lofty bustle and clamour of the capital’s busiest shopping street, it in fact measures almost twenty feet in height.

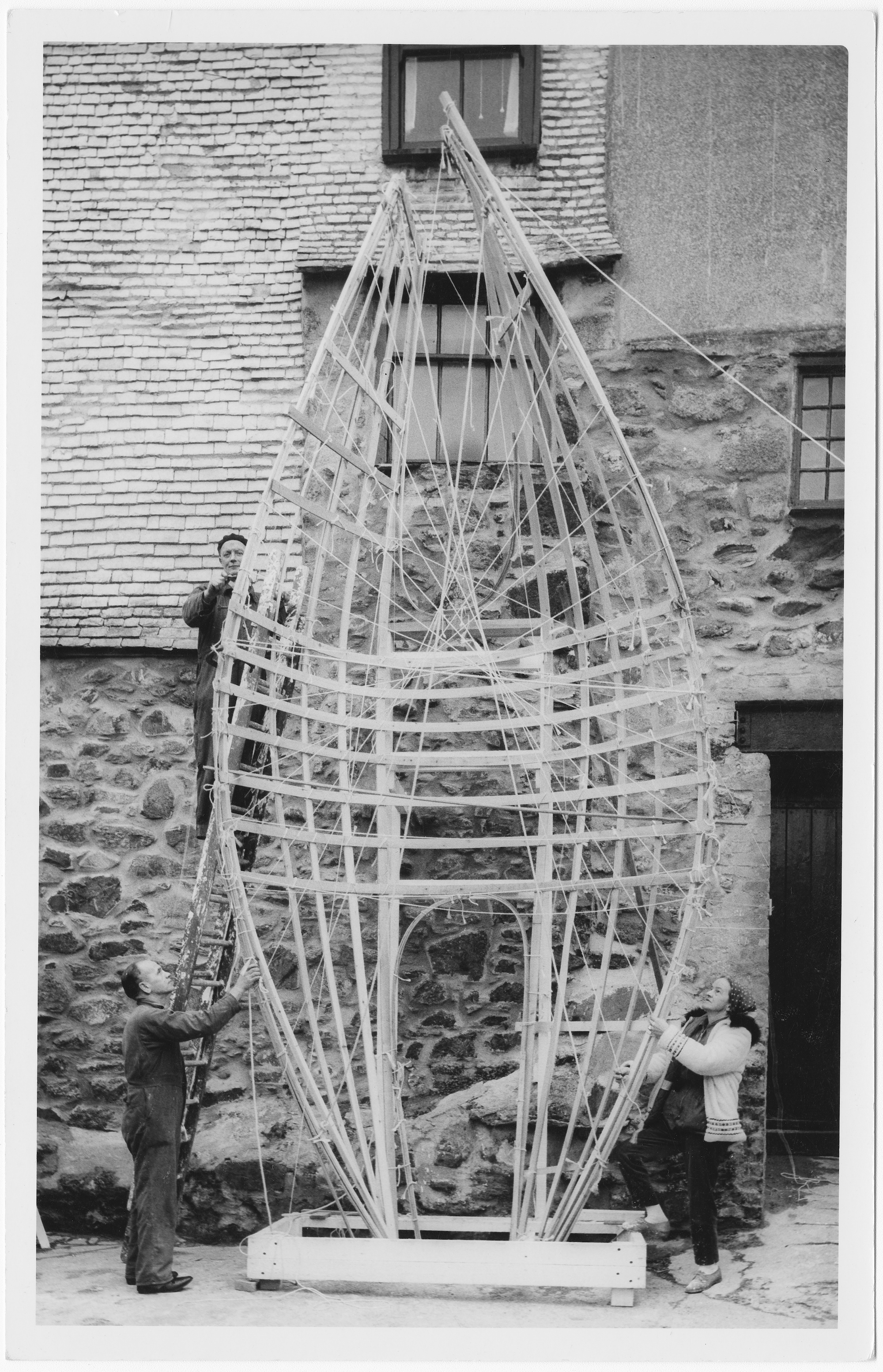

Although I was familiar with Hepworth’s work at the time, it wasn’t until I came face-to-face with a towering prototype of the Winged Figure at the Hepworth Gallery (which opened in 2011 in her hometown of Wakefield) that I fully understood what it means to be overwhelmed by the all-consuming presence of her work. Years later, walking the same few paces between Oxford Circus and Bond Street over and over and over again, the profundity of having stood in such close proximity to this work of art stayed with me. I remembered how reassuringly small I had felt before it, as if nothing else mattered in the world.

When, nearly five years later, my first romantic relationship came to an end, Winged Figure was still there. I walked past it every single day, and each day I processed a new set of feelings. Amidst the heartbreak, grief, anger, despair, guilt and loneliness, a sculpture, created decades before I was even conceived, was just mine. It was a reminder of home, of naivety and of life before the loss of love. Even now, when I return to London for work or to see friends, I am reminded of the fact that I, like Hepworth, am first and foremost a woman from Yorkshire. I, like Hepworth, am a woman with ambition and drive independent of my relationships with anyone or anywhere else.

“Amidst the heartbreak, grief, anger, despair, guilt and loneliness, a sculpture, created decades before I was even conceived, was just mine”

In June 2015, the largest retrospective of Barbara Hepworth’s work to date opened at Tate Britain, titled Sculpture for a Modern World. It couldn’t have come at a more poignant time. That summer, unbeknown to any of my close friends or family, I was beginning to struggle with my identity as a young, frequently disempowered woman. I wasn’t sure I wanted to be another man’s employee or girlfriend. After two years in London, I was detached from my family and former life, but wasn’t entirely comfortable in the world that I’d invited to surround me.

During this time I struck up an unlikely friendship with an older male curator, who made a deep impression on me with his unconventional views and knowledge. We would talk endlessly, as though we might at some point stumble across the secret to enlightenment. We never did, but he did answer all of my questions without reserve. We visited the Tate exhibition together, and it was there that he did something that I never expected. He asked my

opinion on the curation of the retrospective. It was a rare occurrence in my life at that time. In that moment, for a fleeting second, I felt like the most important person in the world.

While the exhibition undoubtedly moved me, the high ticket price for entry felt like a blow to all that I had loved about Hepworth in those first days and months after my arrival in London. Meanwhile, many of these works came from private collections and could only be viewed through glass. It undermined what had always connected me so viscerally to Winged Figure. I had come to view Hepworth’s works as articles for public consumption, available to visit at any time of the day or night. As someone with no formal art education and a working class upbringing, my first encounters with art were at free art galleries or public installations; my father had always told me that art is for everyone and should be accessible to everyone.

Winged Figure has been on show to the public, on the side of a department store, since 1963. To look back now is to realise just how much that principle of openness means to me, and how much it has shaped my outlook in both my professional and personal life. Hepworth’s sculpture reminds me of the path that I have taken to become who I am today. Even from its place above one of London’s busiest streets, Winged Figure takes me back to my roots.

All images courtesy Hepworth Wakefield

Did an Artwork Change Your Life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to office@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life”.

Head to Artsy to read their latest story in the series, a piece on Sally Mann’s Immediate Family by Matt Williams

READ NOW