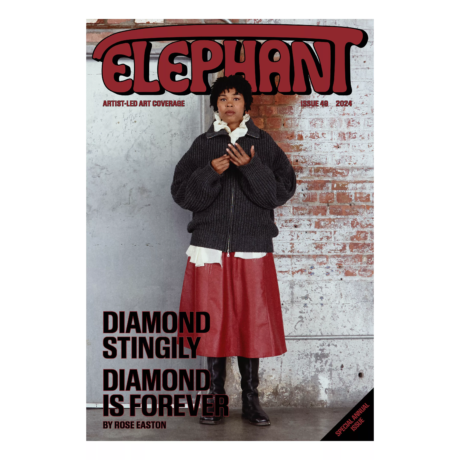

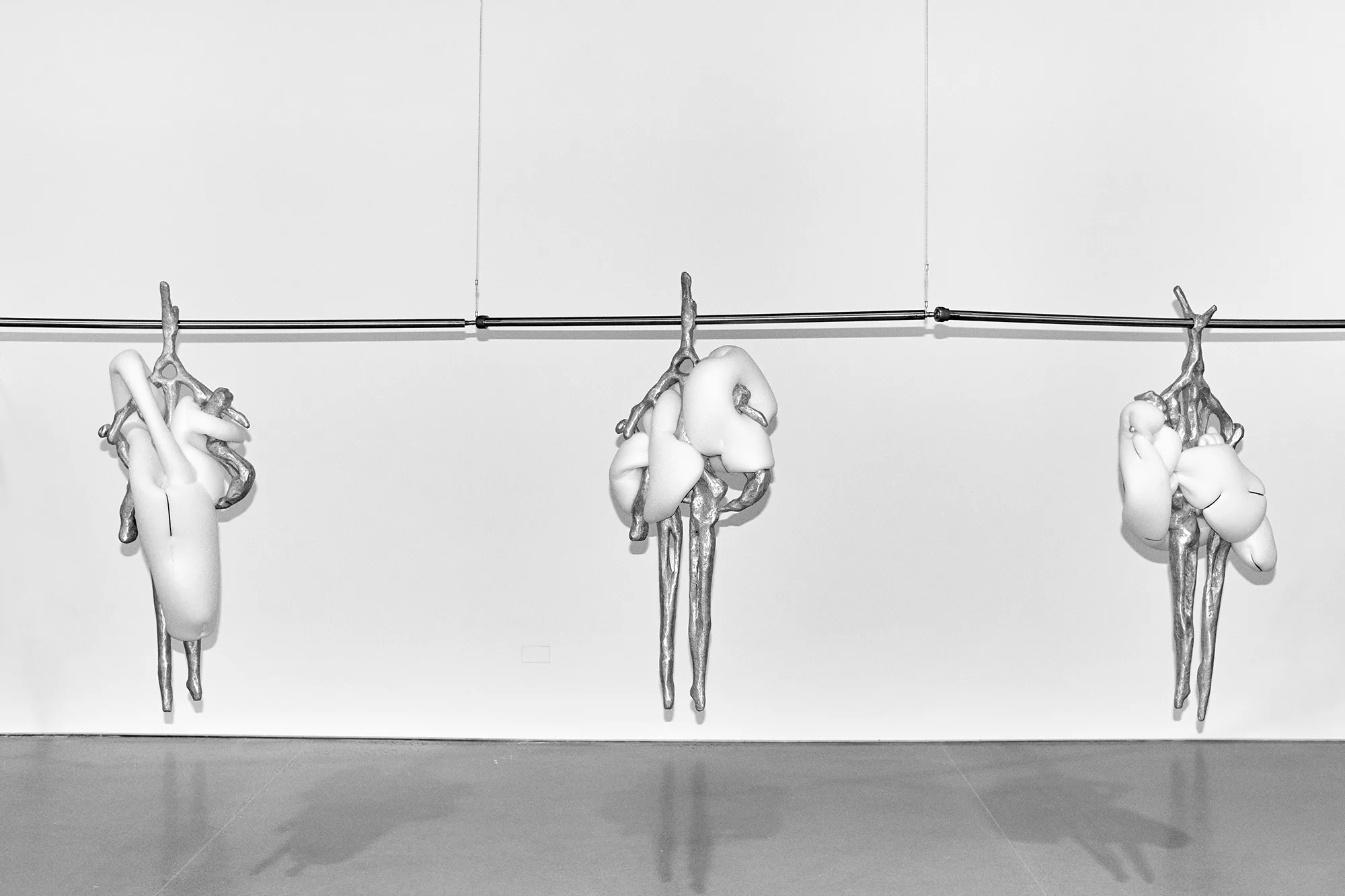

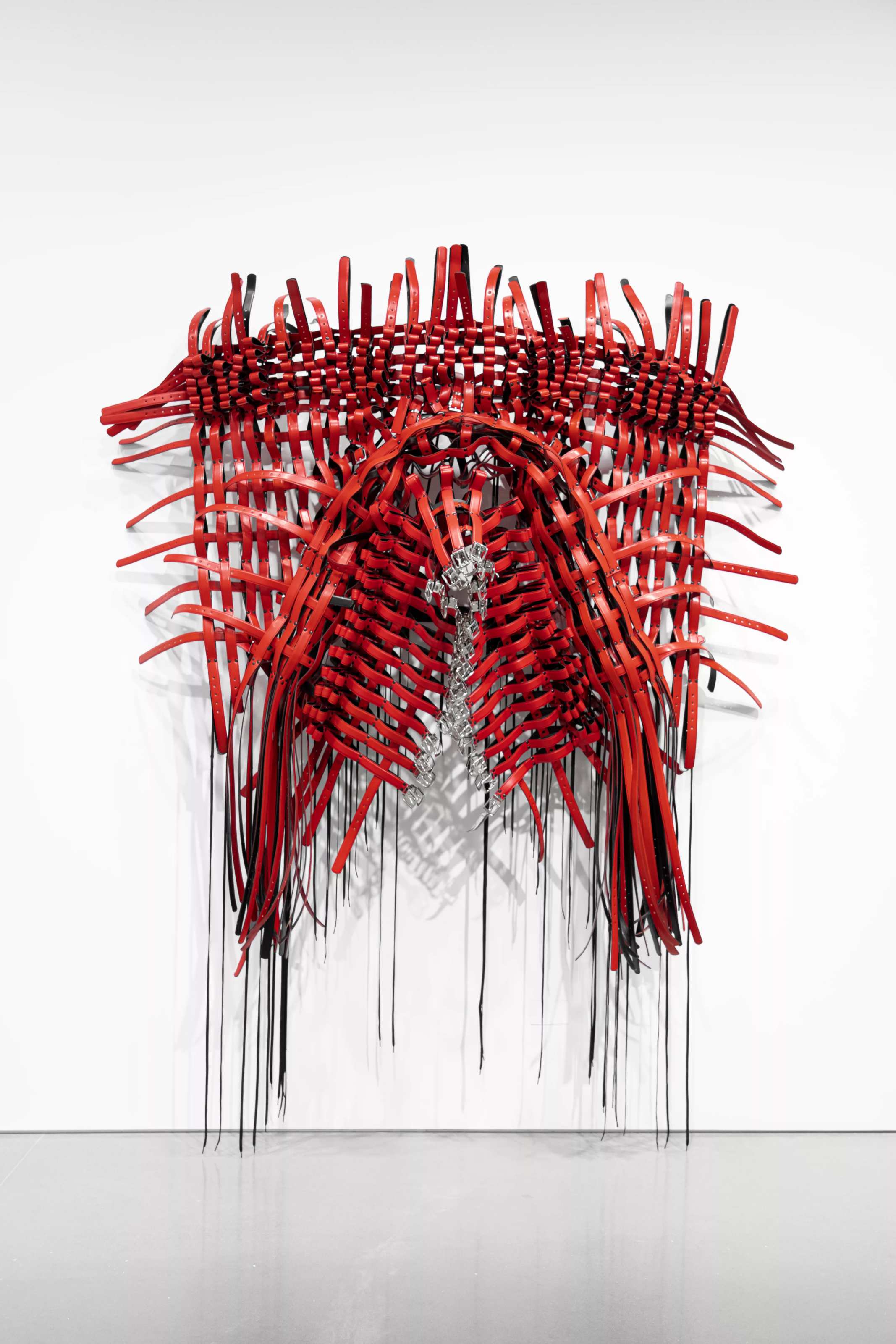

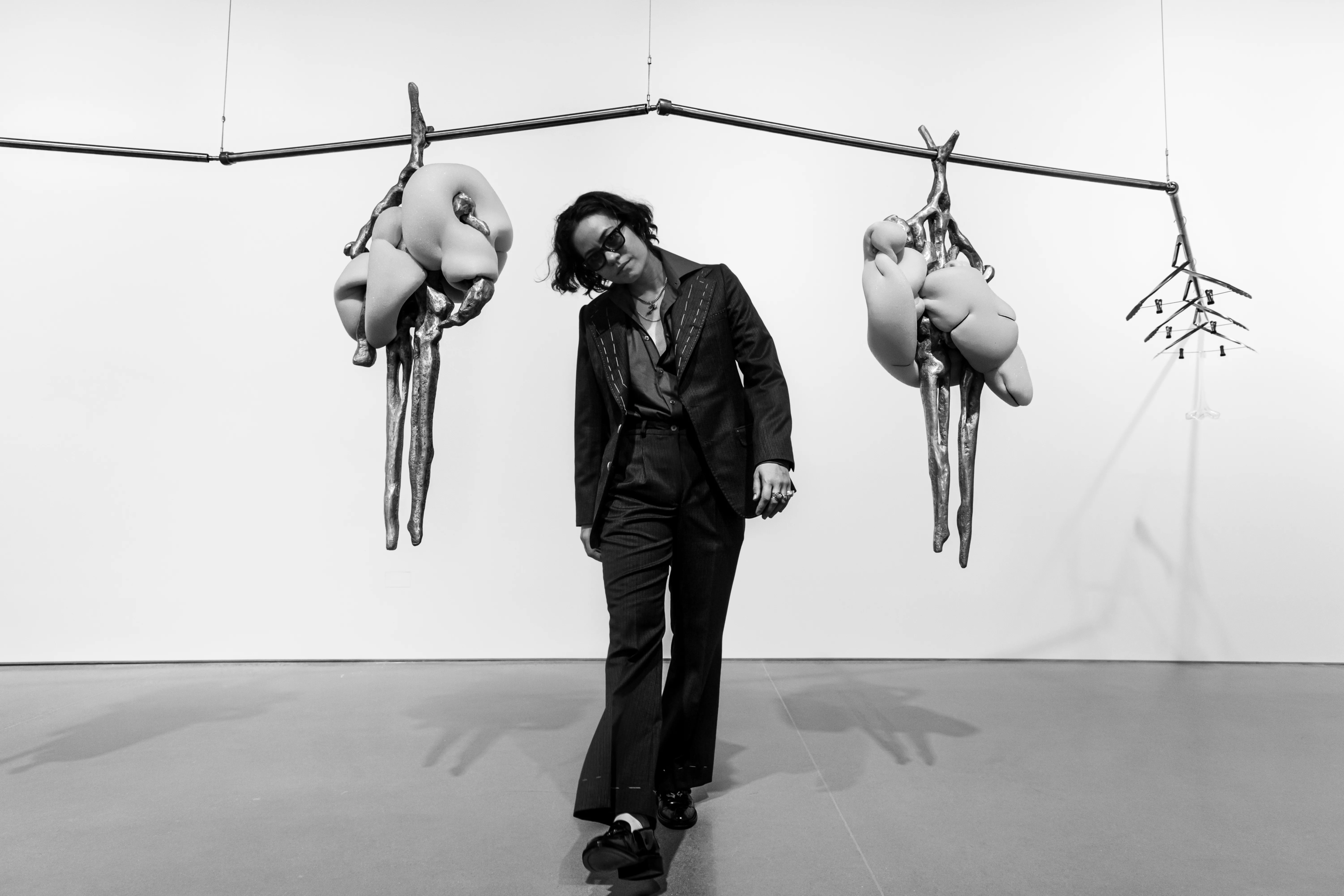

Bárbara Sánchez-Kane, whose work was recently included in Foreigners Everywhere the 60th Venice Biennale Art Exhibition, launched her eponymous brand in 2016 and soon got recognition for fluid and boundary-pushing creations existing between art and fashion, often ridiculing power trough bold gestures: a strap-on with a measuring tape instead of a dildo, a sexy corset made of boxing gloves or three mannequins in military suits with open backs, revealing flirty red lace lingerie, stacked on each other like a human centipede. Increasingly, Bárbara has moved away from fashion, not because of a lack of attraction to clothes and the way the work relates to the body, but because of the fast pace of the industry, making it impossible to rest in exploration. When we get on the phone, she had just opened her show new lexicons for embodiment at Kurimanzutto in New York. It’s her second exhibition with the gallery and the artist’s first solo show in New York. While the objects still reference the craft in which she’s trained, the wearable sculptures have been abstracted to the point of losing their function. The impossible fashion, Sánchez-Kane says, might introduce new ways for the body to act and be in the world. Perhaps it can slow us down in a world moving all too fast.

Nora Hagdahl: You just opened the show new lexicons for embodiment at Kurimanzutto in New York. What’s next?

Bárbara Sánchez-Kane: Well… I just got back and now I’m cleaning my studio. I have to throw everything out. I’m rehanging all my art. I need a fresh start to be able to invite new things in. I’ve been working towards this exhibition for a year. It’s good to have this cleansing ritual before starting something fresh. I feel a need to start over.

Nora: Like a clean slate?

Bárbara: I’m not sure what it’s going to be yet, but next year I would like to present a ballet. I’m still just exploring this, making sketches of images I see playing in my head, of bodies and movements. I think that will be my next step.

Nora: Why dancing?

Bárbara: In dancing you put your body on the line, it’s a fragile expression, always balancing between disaster and brilliance. Dancing is difficult, while watching you get this feeling that something could always go wrong. I’m very attracted to that feeling. In the exhibition I used silver nitrate to chrome rawhides – that process, like dancing, is very much about balancing on a thin line, one little mistake and it’s all ruined. In a chroming lab you find all these faulty pieces, like testimonies to tiny missteps.

Nora: Tell me about the show in Kurimanzutto, what’s it about?

Bárbara: With my practice, I’m always interested in exploring how sculpture can become body or the body become sculpture. I’m fascinated by this symbiosis between the body and what it’s wearing. Whatever you put on, it says something about who you are. In my work, I look into the act of getting dressed and how we create and transform identity through what we put on. Sometimes it’s hard to say who’s the host and who’s the parasite in that relationship – who’s really wearing who?

I aim to corrupt the way we normally treat objects in the gallery. Sculptures are thought of as these pristine objects; we’re not allowed to touch them and they have to be conserved a certain way. My work has a direct relationship to the body which is important to me. When you enter the show, you’re given a newspaper where you see all the sculptures being worn by a model. In that sense, it’s also a reconstruction of a fashion show.

Nora: The show is very much giving “deconstructed store”. There are shoes on pedestals made of shoeboxes and a rack with some hangers, but nothing is really what is seems; as you get closer to the shoes, they turn out to be two little resting Jesus figurines in brass, the hangers are bent kitchen tongs.

Bárbara: I was outside the gallery having a smoke just after we opened and saw this very confused man tapping in “kurimanzutto” in Maps. It really looks like a department store. I like when people think of my sculptures as wearables, it makes the work be more about a relationship you have with the world, with the body, with the streets, lovers and friends. I like that people think they can make my work their own. When making the show, I got really into this book about how to decorate a shop window to attract flaneurs with still-life and how to direct the gaze of desire. The show was somehow a way to merge the aspects of the shop window: to make the scene, the pedestal and the object of desire one. I like to make the arty guy feel like he ended up in the wrong place, instead attracting some fashion victim, looking for new vintage shops, to the gallery.

Nora: You started your career as a fashion designer after finishing fashion studies in Florence. In 2016 you launched your own brand, but then you moved further and further away from the world of fashion, into art. What’s the relationship between art and fashion?

Bárbara: Fashion and art have always been related. In the beginning of brands like McQueen or Margiela there was no clear way to tell if it was art or fashion. But because of the fast pace of the industry, it all became very dissolute. Fashion has always played a part in painting, sculpture and performance. But imagine doing a solo show for an art gallery every six months. The rhythm is impossible to sustain, it reflects in the work. In art there is time for failure and fragility which I feel comfortable with, it’s allowed to be a process of discovery. I think it’s interesting to meet halfway.

Nora: What’s your view on genres? Your work has generally been about blurring boundaries.

Bárbara: All the sculptures in the show, the belts for example, can expand and contract. You know these mannequins whose size you can change by turning a wheel? I bought one. My work became a way of exploring and questioning the size of the body in the industry and making objects that can morph and change. I like the idea of a sculpture not having a definite form, I guess that relates to how I view boundaries.

Nora: Your practice is always coming back to the body or lending its shapes from fashion. How come you started making clothes and use fashion as your medium?

Bárbara: I started studying fashion when I was 22, after finishing a degree in engineering. I grew up in an environment that wasn’t very creative. I never really knew what I wanted to do with my life, but I loved getting dressed up and I’ve always designed my own clothes – so I thought, why not study fashion? The transition from Florence to Merida was easy, both cities are small so it felt more familiar than if I’d moved to London or something. Italy was a time for discovery, before that I’d just followed in my parents’ footsteps. I met a lot of artists and we had a great community in the city, but I never planned or expected to be represented by a gallery. During the pandemic, I moved back to Meriden to be with my parents. I had just made a collection, but there was no way of selling it. That’s when I started approaching making clothes more as art. I started making stuff from what I had around me. But the brand is still up and running, for me it’s the same practice. It’s about the in-betweenness and experimenting with materiality.

Nora: In one interview you asked the question: “Do clothes change how we perceive the world, or the other way around?” I wonder if you could answer this? What’s the power of clothes, style and identity performance though signifiers?

Bárbara: It’s the first confrontation you have with other people. I think the act of getting dressed, or even window-shopping things you can’t afford, is about imagining yourself wearing something – being someone – even if you can’t touch it. It’sabout creating who you are. What I like about it is that it’s a fluid way of performing identity, you can always change the way you are. Someone asked me if you could wear the small Jesus shoes featured in the show, and I said of course, just find a belt and strap them to your feet. What it will do is that it will slow you down, but maybe that’s what you need. Society moves so fast anyways. Perhaps the impossible fashion can distract us and shift our focus. Today I really didn’t bother dressing and I’m sitting here in my pajamas.

Nora: Even you sitting here in your pajamas is some kind of performance.

Bárbara: I’m also really interested in how people add to already designed clothes to make them fit their needs and the way they are, say you add a pocket to something you bought downtown because you need it. Clothes can also hold so many memories. It’s really like a second skin. For me, tailoring is really important. Around the chest area is usually where you have the most inner lining, it makes a jacket almost like armor. I often make cut-outs in that area in my designs, it becomes a way of breaking the thing that gives you stability. It’s kind of the same thing as the belt sculptures, it’s about exposing certain areas.

Nora: It’s a beautiful analogy for looking behind the mask. Do you want to tell me about your concept of the “sentimental macho?” What does that mean to you?

Bárbara: It’s gone, I killed it.

Nora: Gender roles and feminism are themes you’ve worked with a lot over the years. How do you feel the discourse around feminism and gender has changed? What’s the state of feminism today? Do you not feel it’s still relevant?

Bárbara: Of course it is. But in the market we’re in, everything becomes a target, people always try to pin you down and put you in a category. Feminism has become a marketing tool. My work is about a lot of things, and I feel like people have been wanting to put me in a box as an artist only working with those questions, which is also the reason I quit the“sentimental macho” project.

Nora: I guess as a female artist, it’s quite easy to get trapped in categories such as the “feminist artist” or the “artist talking about disrupting gender roles,” also because people tend to find these explanations really easy to grasp. Especially a couple of years ago, it was the way to make a headline, right?

Bárbara: Exactly. It started to get really absurd in my opinion. I feel like my work is running on more existential levels, beyond identity. It’s about being this Trojan horse, entering people’s minds or touching their skin. It’s intimate. Feminism is there, even if you’re not talking about it directly, it’s in the act of provocation.

Nora: You often work with deconstructing an object, obscuring a form or making ridicule of something familiar. What happens in that process of deconstructing in your opinion?

Bárbara: By transforming recognizable objects, I feel like you neutralize their charge. It becomes a new thing: a little monster or parasite or whatever. I started making clothing patterns by analyzing toys and imagining objects that don’t exist, and maybe don’t even have a function. The process was to then design that object, and give it yet another function that it didn’t have from the beginning, in my mind, or just to design the cover or shadow of that object. It’s always important for me to work with objects that surround me, and try to make them something else.

Nora: What’s humor to you? I feel like your work is infused with a lot of humor.

Bárbara: Sometimes the work even makes fun of me. But humor is hard, it has a short expiration date. What felt really funny two years ago just feels like a dad joke today. In Mexico City people use humor a lot to resolve conflicts, humor is everywhere here.

Nora: I was reading the copy on your website, and found it really hilarious. ”Calzón Tank Top is the perfect addition to your summer wardrobe. Upgrade your fashion game with this versatile tank top today.” – for me, it reads like you’re making fun of the fact that you have a brand and sell things; humor becomes a way of fetishizing the whole situation.

Bárbara: My head of studio used to write that copy, and she thought it was very corporate professional. I just let it pass, I thought it was fun.

Nora: Oh, I really thought it was intentional. How do you reflect on still having one foot in fashion? You still sell clothes.

Bárbara: I don’t think I will ever leave it; I really adore it when people write me an email, come by the studio and try on my clothes and I can show them how to put things on. Maybe I used to have these goals of showrooms in Paris and so on, but I don’t have a huge production, and I like it that way, I like the intimacy.

Nora: Does it change the way you view your own work when it has to exist in other value hierarchies, such as the art market or in the gallery? Do you feel you lose something when doing that, as you remove yourself from the everyday aspects that fashion has? Even if fashion’s commercial aspects can be problematic, it’s still a way to really insert your work into people’s lives, it’s really accessible and available in contrast to the object on a pedestal in a museum.

Bárbara: I always wished I would find a piece of mine in a second-hand kilo shop.

Nora: If someone buys something from you for 200$ they will use it, they will make it theirs. But if they buy something from your gallery, they might just put it somewhere.

Bárbara: Haha, yes, and then they call you and ask you how to conserve it. Have you ever been to these people’s houses where they have a thing they don’t show to a lot of people, that they bring out for special occasions? You’re not allowed to touch it or play with it… The idea is that my sculptures should be worn and torn, and maybe they change color and break because you do. My dad always wears his shirts until they break on the elbows and then takes them to get repaired – the scars become part of a new landscape, they add to the objects and create new points of view.

Written by Nora Hagdahl

This feature originally appeared in Elephant #49

buy it here