New York- I met Liao Wen on the Tuesday morning after Frieze New York in an airy, sun-lit coffee shop attached to Legacy Records in Hudson Yards, a short walk from where the Chinese sculptor was staying, fresh from winning the art fair’s 2023 Focus Stand Prize for her solo show Naked with Capsule Shanghai, featuring wood figures holding poses so impossible that they might bend or buckle from their own weight, but they don’t. Liao’s androids are perfect; they embody human aspirations and limitations.

Outside our enclave, the hustle and bustle of Midtown trickles over: a steady flurry of businessmen, tourists, and construction workers. Nearby, galleries are opening their doors in Chelsea to pick up the final wave of art-world out-of-towners still in the city after Frieze.

It is the 29-year-old artist’s first time in New York and, in fact, America full stop. She is from Chengdu and currently lives in Hong Kong. Still, she seems to have already settled into the pace of the city, bouncing from galleries to museums to studio visits (some arranged by her gallery, some meet-ups with internet artist friends). Also on her itinerary are visits to The Here and There Collective, a nonprofit that supports Asian artists; the Sculpture Center; and the Noguchi Museum.

By the end of the week, Liao will have managed to catch an impressive roundup of major museum surveys in the city: Wangechi Mutu at the New Museum — a show that nearly brought her to tears — Cecily Brown at the Met, and Sarah Sze (“a genius”) at the Guggenheim. These artists are a North Star for Liao, who is excited to see the representation of mid-career female artists in major museum spaces, something that their Chinese contemporaries of the same generation are rarely afforded, she tells me.

With only a few days of free time under her belt, she has already visited the studios of numerous New York-based artists, including Sarah Faux, Vincent Cy Chen, and Douglas Reiger. The latter (a sculptor who, like Liao, is represented by Capsule Shanghai and works with wood) exchanged tips and tools with the young artist, who herself has an extensive collection of woodworking devices. “I was so curious,” she says of Reiger’s studio, pulling up an image of one of his tall, abstract sculptures before swiping to a close-up photo of a smorgasbord of sharp instruments and miscellaneous objects. “This is a kind of glue to fix the crevices of the surface on wood,” she points to a small white tube on her phone.

“Recently, I’m thinking, maybe I will show some crevices,” she muses. “I don’t want to fix everything anymore because making the surface perfect is so exhausting. But I need to think about it more because it’s not just the surface; it’s a whole idea.”

And for Liao, ideas are the lifeline for her one-of-a-kind, human-like androids. Thankfully, she has many. She is at the exciting stage of a promising career: her work is getting noticed internationally. “The response at Frieze was beyond my expectation,” she tells me over an egg tart and black coffee. “I learned how to carve wood from making puppets, so I didn’t come with any ideas or stereotypes about making sculptures,” she says. “My sculptures are different. At Frieze, many people who saw my work were quite surprised. Maybe it doesn’t mean I’m good, just different,” she humbly offers, adding that the fixation on her work as robot-like wasn’t entirely expected: she set out to evoke the human body, after all. Although, the connection between man and machine is not lost on her.

“Puppets were the precursors to robots,” she posits. “Before we invented robots, we used puppets to perform — as a substitute for human beings. If we ask ourselves: how do we deal with the relationship between human beings and the robots we invented? We should also ask, why did we invent them? Why do we invent human-shaped things? How do we recognize ourselves?”

These questions reverberate in Liao’s work. “For me, puppetry is a way we project ourselves into puppets, just like we project ourselves, our desire, our incapacity, or so many things we cannot achieve, onto robots, onto AI,” she adds. “We actually expect them to surpass our abilities. But on the contrary, once they exceed us, we feel horrified. So this is very contradictory.”

It is here in this contradiction that Liao finds inspiration. Her sculptures are practising an endurance test with no end in sight. Their smooth wooden bodies contort until they reach their limit, frozen on the precipice of release. They bend until they almost snap, bearing their weight on their toes, holding in fluids.

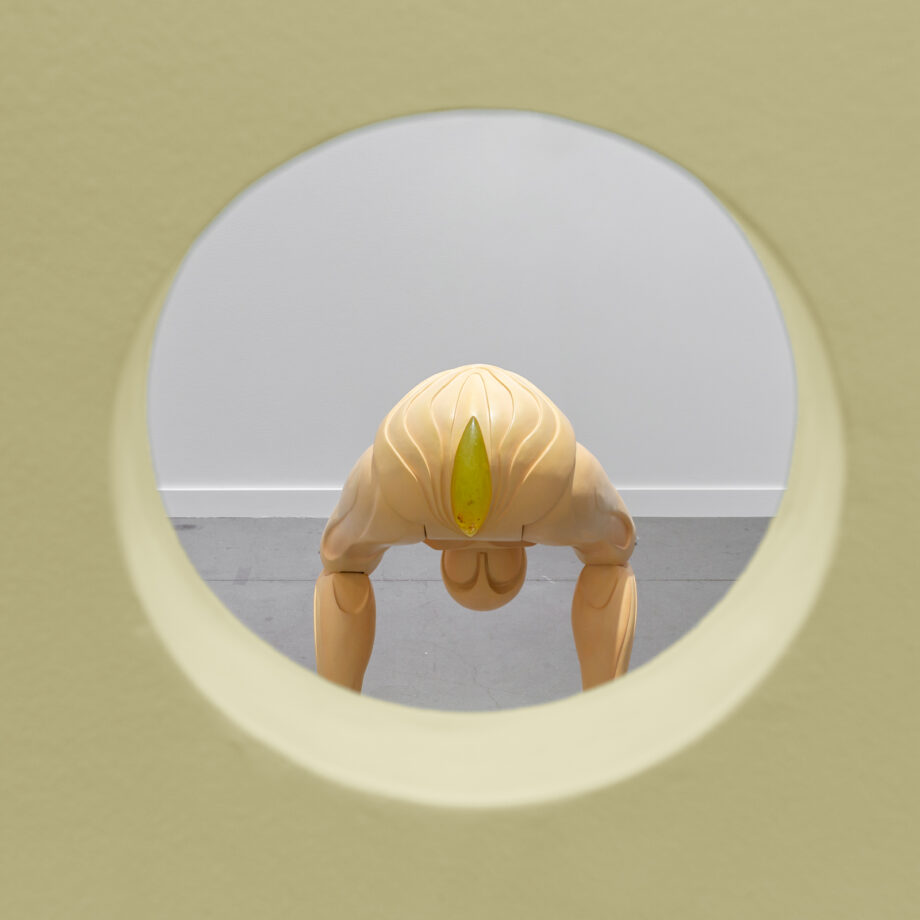

At Frieze, a pale yellow wall with a peephole frames Stare, 2022: a large, smooth hand-coloured nude limewood figure. Two large eyes peek out from behind her vagina, which is aglow with urine-yellow resin and specks of what looks like blood. Where some might see eroticism, Liao sees introspection. The sculpture’s naked body bends over, away from the wall, precariously leaning forward, balancing on the balls of her feet to inspect her hole. A human could hold this pose for seconds; a trained dancer or acrobat might fare longer before buckling from their weight; Liao’s sculpture can hold it forever.

“The sculptures are my androids; they are my puppets; they can endure it. They are perfect actors. They are much better than human beings,” she says. She kicks down her black Z-Coil sneakers, stands up, and stretches out her arm towards me. She extends her elbow as straight as possible, securely resting her phone on her open palm. It is at the limit, she explains, that her arm is best supporting her hand, bearing some gravity so that it can hold the phone without falling limp.

While her arm would get tired and eventually drop to her side, her sculptures are crafted not to fail — human in the pursuit of perfection, android in their achievement. “They are also an extension of you… you’re pulling the strings,” I posit. “The string is invisible: it is my design, the way I manufacture the joints,” she agrees.

Their limber bodies have joints that move. Liao tries out different positions for each work before settling on a pose. For every large-scale work, there are miniature models and studies that push the form to its limit before it expands in size. It is a physical feat, says Liao. The wood is heavy, as are some of the tools.

Her technique harkens back to the artist’s days studying puppetry in Prague in 2017 through a study abroad program at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where she earned a Master of Fine Arts. During the month-long program, she learned how to carve puppets and stage plays. On her off time, she would watch the dance troupes that immersed the town in the summer. Eventually, after her training ended, she found herself gravitating to the more conceptual, open-ended world of sculpture where she could stretch her ideas.

In Her Room in the Dream, 2018–19, which debuted as her graduation project at the CAFA, Liao placed a marionette version of herself amidst a room filled with personal ephemera: a television, manuscripts, anatomical models. She performed as the puppet master before cutting the puppet’s strings. Later, the installation travelled to group shows with a filmed version of the performance.

The next year, for her series Birds of Passage, 2019, she turned her gaze outward to reflect the identities of displacement of migrant workers in Shenzhen. She invited workers to create dolls in their likeness and then asked them to place their puppets in meaningful places, as well as places they hoped could have meaning one day.

In her installation Poisons or Antidotes, 2021, Liao’s wooden figures emerged, larger and more android-like, shedding personal identity for shared stories of the body. Their taut wood limbs were displayed across a gallery-turned-garden-bed floor planted in the soil. In Wind Passing through Our Bodies, 2021, she replicated the roof of her home, where her family would grow medicinal herbs like mugwort.

As I look at her current work, I suggest that maybe she never stopped creating puppet shows. If we look long enough, might we catch her wooden figures readjust their footing, stretch out, and collapse, signalling the end of the play? As long as Liao’s puppets can hold their composition, the play goes on. There is no final curtain in sight. These perfect cyborg-like beings can only point at our own thresholds: theirs is limitless.

However, unlike theatre, where narrative rules, Liao’s installations invite the audience to project their own stories, she discerns. “With sculpture, you have to make room for emptiness for the viewer.”

And Liao’s work is pregnant with an emptiness that leads the viewer into uncharted territory: bodily functions often overlooked or repressed. One work, titled Hesitation, 2020, is pregnant. A nod to Louise Bourgeois’s Maman, 1999, a spider sculpture that recalled the complicated protective qualities of motherhood, Liao’s work is teetering on the brink of its predecessor. “It’s about abortion. It’s about deciding between being a mother or not,” she explains for the first time. “It’s about your own future. It’s about your own body. It’s all about the possibility of a small tiny life. It’s about an intrusion in your body. It’s very complicated.”

Hesitation captures all of the contradictory emotions that arise when a woman first finds out she is pregnant — the emotions she might be too afraid to share, the long, laborious, and thoughtful pause that comes before a decision. Previously, she had left the meaning shrouded in the title, hidden for the viewer to unravel in the figure’s contorted body that curls inward against the weight of some omnipresent force. Upon closer inspection, a bloody ruby glistens from a spindly, hook-like appendage tucked underneath her body; it cradles (or probes?) an exposed silicone sack.

“How do you depict something you cannot see but you can feel?” she asks. “We barely notice the existence of our body except when..” she pauses to lightly pinch my leg. “Now you feel your leg.”

I suggest that in Western medicine, there is a disconnect between the body and the mind. In China, there still must be a holistic approach to the body, right? “No, it has also become Westernized, more modern,” she says. The robot-like detachment is universal. “Why do we neglect our daily body feelings? We only pay attention when we feel sick or injured,” she adds.

On a mission to find humanity in overlooked bodily rituals, Liao zeroed in on everyday occurrences: salivating, inhaling, sneezing, and nausea. In Throw up, 2023, one of Liao’s more recent works shown at Frieze, a flesh-toned torso captures the feeling of nausea: three translucent, crystal-like eggs made from epoxy resin and jesmonite bubble up from the esophagus as two thin bands of metal wire hold the stones down.

When Liao isn’t carefully contouring her bodies, and labouring over the cracks, she is diving into research. Bourgeois’s spiders, Francis Bacon, Eadweard Muybridge, the Roman votives, Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World, images of women urinating, and pornographic images blend together. Her references, filtered through the artist’s idiosyncratic lens, only become apparent after studied observation.

As she prepares to return to Hong Kong, Liao ruminates on the way bodies are cramped and condensed in tight, metropolitan spaces. With her studio now in one of the most densely populated places in the world, an island with over 7 million residents, bodies packed in elevators, on streets, and in high-rise buildings, Liao is curious about urban planning — the relationship between city spaces and the people that inhabit them. What does this mean for the young artist’s next project? Lots of looking: looking at the bodies and spaces around her, looking back at art history, looking online, looking into herself, and as always, looking forward to a near future where robots are not so different from us.

Words by Meka Boyle