Creation and discovery are common tropes used to establish an origin myth. While it’s hard today to consider anything other than islands rising from the sea and skyscrapers coming out of barren sand, the extraordinary urban landscape of Dubai wasn’t always quite as loud, vertical, elastic and boundless.

In his new book, Off Centre/On Stage, curator, architect and writer Todd Reisz excavates an untold Dubai through unpublished photographic vignettes from the 1970s. It complements an eponymous exhibition at the Jameel Arts Center, running until 21 March 2022.

The book’s release and the exhibition coincide with the Dubai World Expo 2020 (postponed by a year because of the pandemic). Until March 2022, it will host more than 190 country pavilions under the auspices of “Connecting Minds and Creating the Future”, a first for a country of the Middle East, Africa and South Asia region.

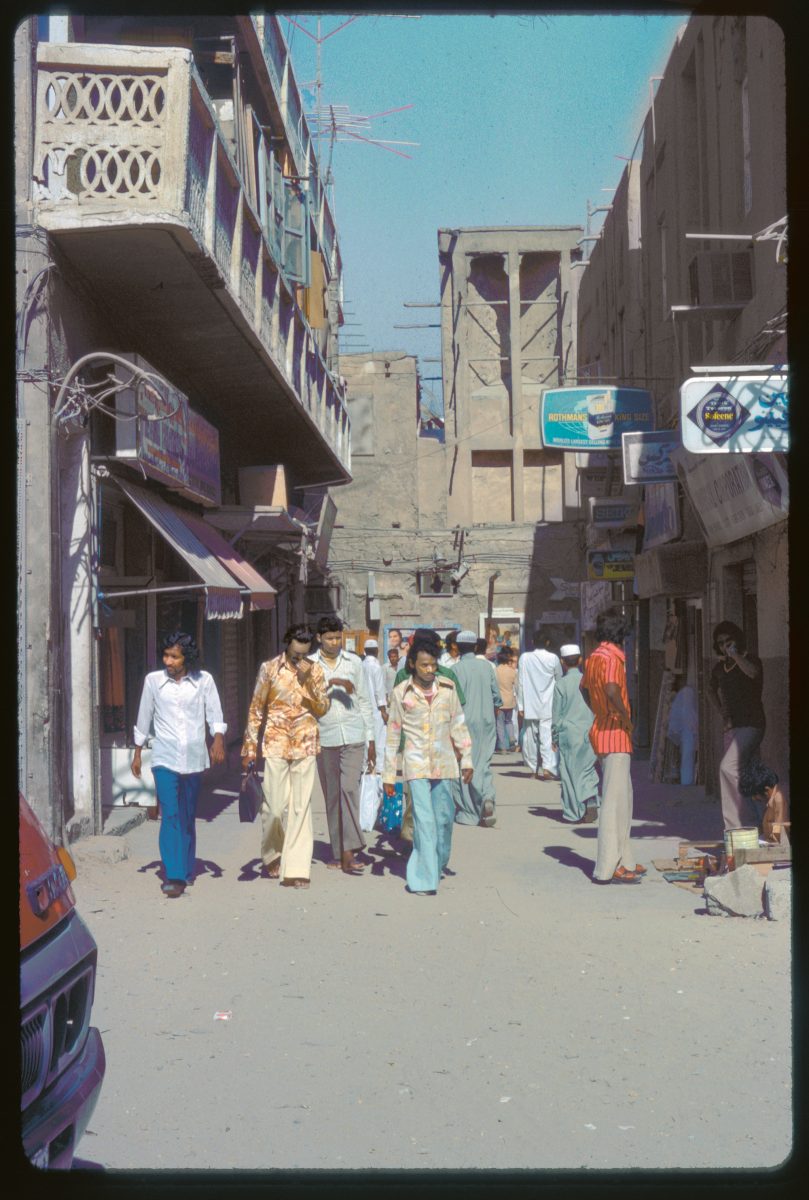

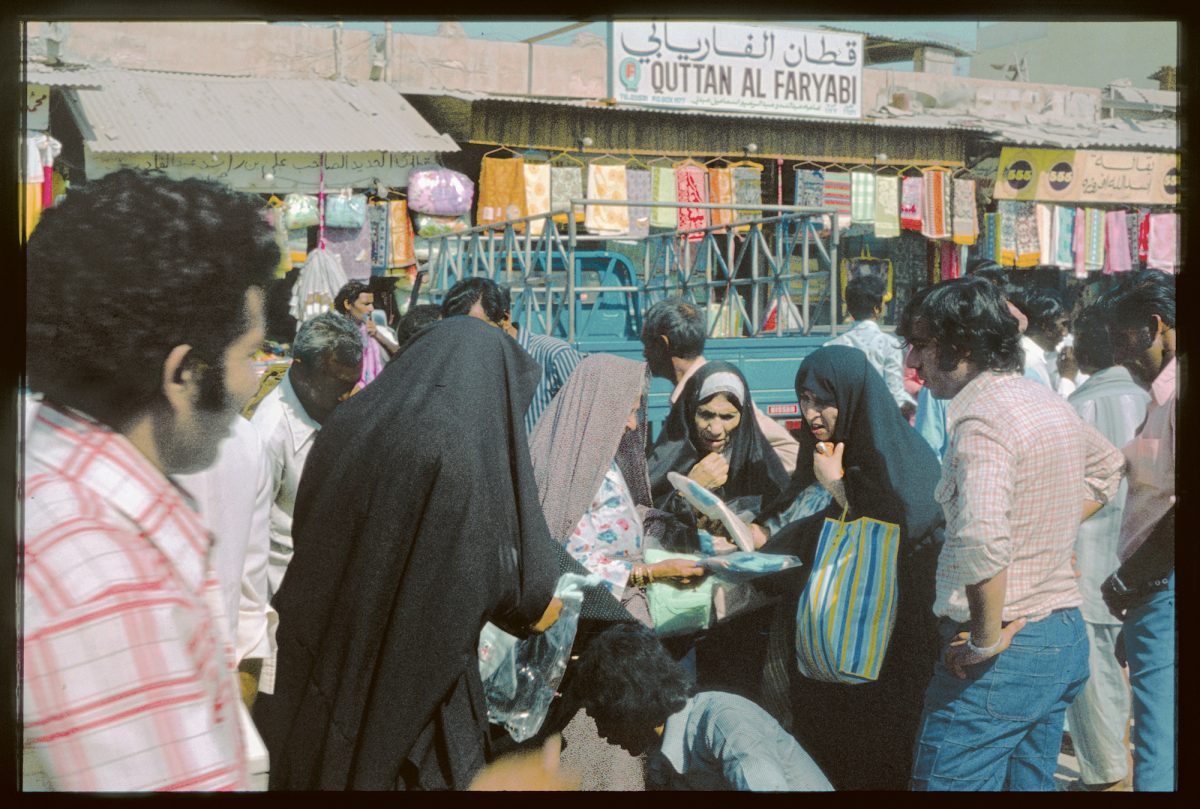

Curating 100 unseen photographs, the book is a time capsule of bulldozed, forgotten realities, the everyday of a city’s past crushed by a determined future. While filled with the saturated hues of the period, they also convey the shadow of modern development and transport the reader in a spatial voyage through overlooked before-times.

“The book is a time capsule of bulldozed, forgotten realities, the everyday of a city’s past crushed by a determined future”

The photos are not “are not commercial, documentary, or art photography,” Reisz writes, but rather “visual notes” from British architects Stephen Finch and Mark Harris, both affiliated with the firm John R Harris & Partners, who directly contributed to Dubai’s urban transformation between 1976-1979.

In 1960, Harris completed Dubai’s first town plan, redrawing lines to elevate structures and connect the port city (which still had unpaved streets) to hospitals, commercial banks and more, all of which was commensurate with the ambition of Dubai’s Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum. Oil would be discovered in 1966.

Reisz previously retraced the role of British experts in selling the “political potential of infrastructure” to Dubai’s rulers at a time when the city opened to global markets and trade routes (Showpiece City: How Architecture Made Dubai, 2020). The ostentatious ease of “doing business”, via honour-based contracts and supportive authorities, encouraged a large array of foreign experts to join Dubai’s great design experiment and claim that their work was detached from politics and interference.

“There is a tendency to look up towards Dubai’s ever-growing heights. Off Centre/On Stage refreshingly conveys the view from the ground”

Yet myth-building is by essence political. As Reisz reminds us, it’s essential to historicise the city as a living, breathing space of past, present and future. The 1970s were a decade of significant change, not just in the city but also regionally, with initial tensions between Dubai and Abu Dhabi over the latter’s centralising role prior to the independence of the United Arab Emirates (previously under an informal British protectorate).

In those days, Dubai sought to project a new image. The country’s future became a collateral for investment which served to attract goods, people, commodities, and leverage other assets. Publicly accessible archives from this period remain scarce and reconstituting Dubai’s urban history involves piecing together disparate fragments of personal memory, anecdotes and fleeting records.

With Dubai, there is a tendency to look up towards its ever-growing heights. Off Centre/On Stage, which is beautifully designed by Huda Smitshuijzen AbiFarès, refreshingly conveys the view from the ground. In this visual stroll and through the non-neutral gaze of the two British architects, one encounters people, presumed to be local, and wonders about their agency. They appear at times as bystanders, spectators, dust in the concrete cloud of emerging shapes and sometimes as ghosts.

The city we see is an open-space construction site. In several photos, one can notice Dubai’s maritime history and its connection with seafaring and fishing. For instance, in a photo dated from 1977, men in their dhows turn their backs to the camera. They lean on their forearms and elbow in a restive posture, on a hot, long day. In front of them, on the opposite bank of Dubai’s Creek is the skeleton of the new Municipal Building. A symbolic past looks at the future and we wonder what they would say to one another.

Farah Abdessamad is a New York City-based writer and essayist, originally from France and Tunisia