“She didn’t just paint flowers,” French novelist Marie Darrieussecq writes in her biography of long-forgotten German expressionist artist Paula Modersohn-Becker, whose career unfolded at the dawn of the twentieth century when many still thought flowers the only proper subject for a female artist. Modersohn-Becker, who died at thirty-one of a postpartum embolism, with so much potential for work still ahead of her and an eighteen-day-old baby, sold only three paintings in her lifetime. She did paint flowers but also luscious proto-cubist fruit, goldfish (before Matisse) and astonishing female nudes, all radiant colour and simplified, expressive form, their surfaces “rough and alive”. Paula’s short life was “a bubble between two centuries”. How did this profoundly original artistic sensibility emerge against the odds? Who was Modersohn-Becker?

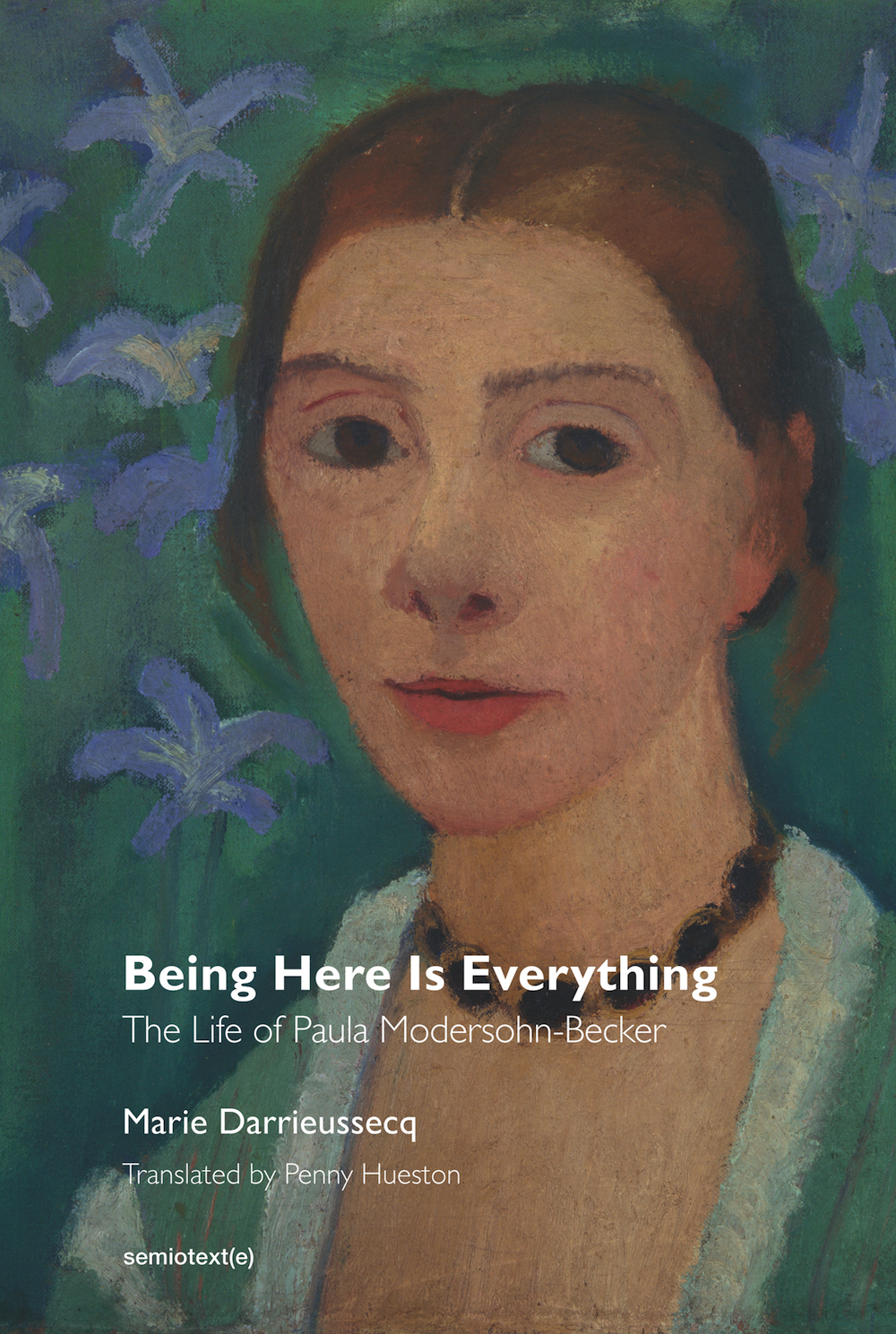

As a writer, Darrieussecq, who came to fame in her twenties with Truismes (Pig Tales, 1996), a surreal fable about a woman metamorphosing into a pig, is deeply interested in the female body and its representations. An arresting, highly unusual breastfeeding nude used to illustrate a conference on psychoanalysis was her first glimpse of Modersohn-Becker’s art. This started a passionate enquiry which took Darrieussecq to Germany, rooting out some of the artist’s paintings from behind television sets in the basement of a museum along the way. The result, this short expressionist biography nourished by photographs, correspondence and journals, acknowledges gaps and contradictions: it is impossible to paint a complete picture of Modersohn-Becker’s life. But what this vivid and thoughtful book achieves brilliantly is a gradual summoning of the artist’s presence: “Paula is here, with her pictures. We are going to see her.”

“How did this profoundly original artistic sensibility emerge against the odds?”

“I am becoming somebody”, rather than Modersohn (her married name) or Becker (just herself), the artist wrote about her hunger for painting. This sent her wandering through “the huge personality of Paris”: “Filth everywhere, and the stink of absinthe, and faces like onions.” She enrolled in 1900 at the Académie Colarossi where she won first prize, and also had anatomy lessons—drawing cadavers—at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts which had just opened its doors to girls. Modersohn-Becker painted what she saw, Darrieussecq writes, “with a naked eye”, yet also included in her gaze Rodin, Gauguin, Monet and Cézanne, especially, who affected her “like a thunderstorm”. Her expressionist use of form and colour repelled her husband Otto, also a painter, who wrote about her “mouths like wounds, faces like cretins”, but she persisted in her search, writing: “There is something almost tactile for me in the application of paint.”

Most remarkable are Darrieussecq’s evocations of Modersohn-Becker’s portraits of young girls and women, nudes in particular, as “worlds of thought” utterly stripped of the masculine gaze, especially her tranquil, mischievous nude self-portraits—an entirely ground-breaking thing for a female artist to attempt—all expressive of a new way of seeing and of representing things previously unrepresented: “Not sentimental, or pious, or erotic: another sort of sensuality. Boundless. Another sort of power.”

Being Here Is Everything: The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker

Out now with Semiotext(e ) / Native Agents

VISIT WEBSITE