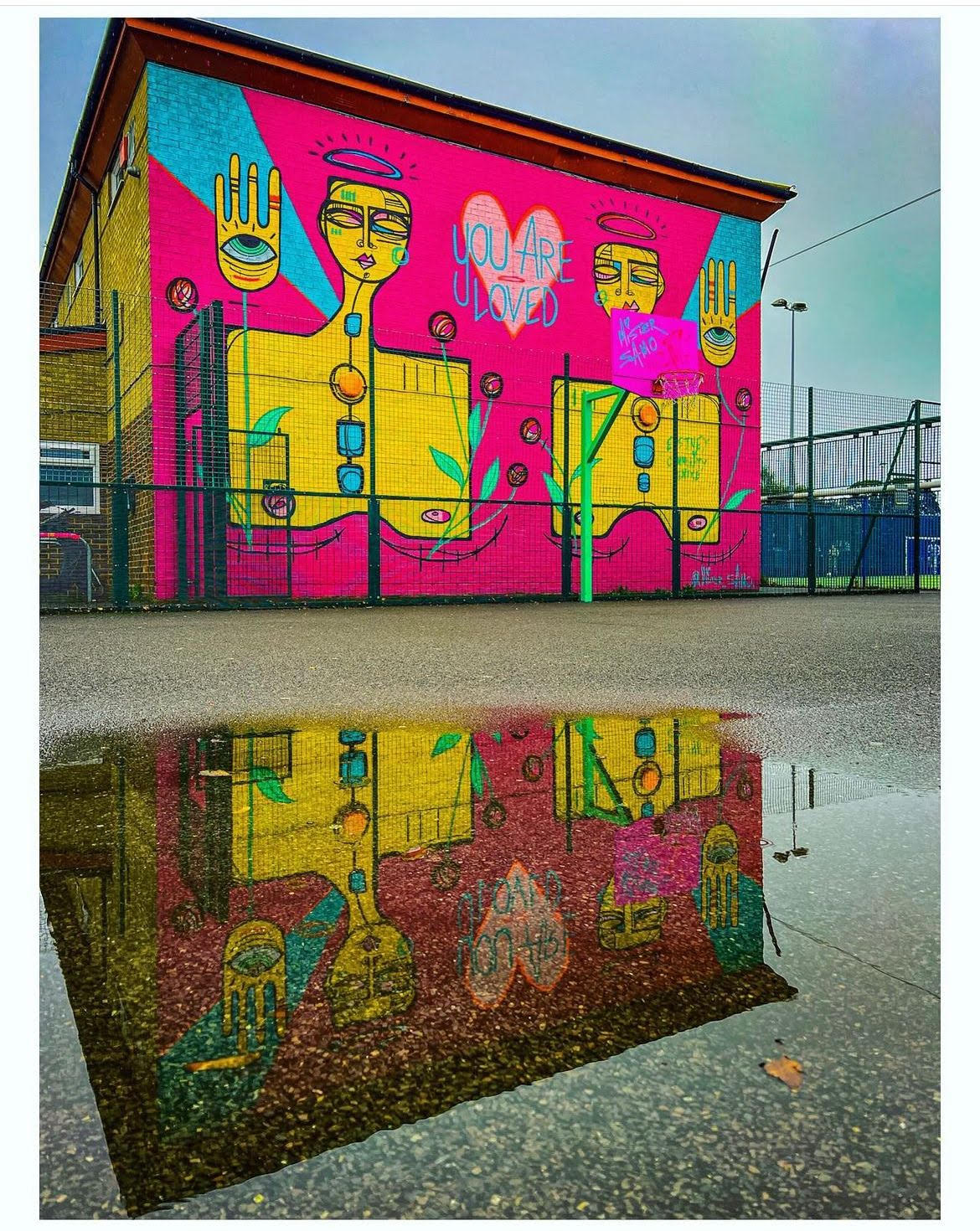

At precisely 2 pm on a Tuesday, I find myself being given a crash course on the rumination of graffiti art by Lady Pink, whose studio could, more or less, serve as a place of worship for it with its congregation of innumerable aerosol canisters. “The streets give us two-story buildings and more; it’s about scale”, she declares. “We like it bigger, and it needs to be outdoors for everybody to enjoy. Museums and galleries are for the cultural elite, and most working stiffs barely have a moment to do their grocery shopping and laundry on the weekend before they roll back to work, and they don’t have time to visit many of these places. So we come to their streets; we’re right around the corner, which makes us part of the fabric of everyday lives. The money for the arts, in most cities, is kept for the better-looking parts of town. They have the sculptures, along with the fountains— not so much the common people, so we look after our own. We’re from the outer boroughs, Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx, and they never see money for the arts, so we beautify our own neighbourhoods and why not?”

If you were to consider it through the perspective of graffiti being one of the singular mediums of expression which were openly turned to by the poverty-stricken and oppressed, her question would seem more satirical as opposed to rhetorical, particularly given that the research undertaken by the Analysis of Office for National Statistics found that whilst 16.4% of creative originators born between 1953 and 1962 had a working-class background, this number has decreased to an insubstantial 7.9% for those born four decades after. In retaliation, the purpose of graffiti is increasingly coming across as being not only to knock down walls but also to challenge the very foundations upon which those same barriers had been built, with voices such as Professor Jeff Ferrell’s “in tagging and piecing for one another, writers also construct alternative systems of status and identity” rising from the rubble in a blur of spray paint, paint markers and stencils. “Both for those kids increasingly shut out of traditional channels of achievement and for those who, through ethnicity or education, retain some modicum of choice, graffiti writing provides a powerful alternative process for shaping personal identity and gaining social status”, he continues. “Black, Latino, and Anglo boys in the Southern California graffiti crew TIKs, for example, have quit high school chess teams and spurned advanced placement classes to devote as much time as possible to graffiti.” Such a vivaciousness has grown through time as much as its instigators have inevitably grown up with the passing of it, particular milestones being young artists political transformation of the Berlin Wall by the time of its toppling and the resistance to Soviet authority through graffiti envisaged on the part of urban-youth cultures.

Meanwhile, in London, animal rights campaigners, feminists, and other provocateurs took to those of the capital’s billboards, which they deemed offensive, whilst, in Northern Ireland, young Catholics rendered murals that immortalised and invigorated defiance to British rule before protestants and the British military struck back with works of their own. In the same manner, Nicaraguan youth groups have continuously painted street portrayals of Sardino as an expression of political resistance and discourse, which post-Sandinista bureaucrats responded to with “mural death squads.” Toronto street artists also envisaged projects that railed against colonialism and stirred up governmental disobedience, whilst young Palestinian militants who were prevented from using radios and newspapers in the occupied provinces turned to wall painting as their chief form of transmission and rebellion against Israeli authority. So, as put by Professor Ferrell, “Why do graffiti artists resist?” In the same way that graffiti is used by gangs to create status and identity, graffiti writers who most commonly consists of youth, use graffiti to create identity and change the flaws of the society,” he reasons. “By resisting the urban control made by the institutions against graffiti, they make it possible to “reclaim public space for at least some of those systematically excluded from it, and thus resist the confinement of kids and others within structures of social and spatial control” (Ferrell 35). The cultural resistance demonstrated by graffiti is a way “to resist and/or change the dominant political, economic and/or social structure” (Duncombe 5).

“When I started in 1981, there was a form of protest and rebellion in graffiti”, points out Blek le Rat. “Moreover, the term street art did not exist. We talked about graffiti but never about urban art or street art. It proves in a certain way that the word graffiti that induced rebellion has changed the concept of art and is an accepted behaviour by some people. In general, the idea of going out in the streets of a city at night when we know the risk we can encounter, I mean police, graffiti haters, accidents, or whatever, is the same real act of rebellion for every street artist. I used to say all street artists go to the same restaurant but don’t eat the same food.”

“Graffiti, like all art, can be the creative voice, face, and instinct of democracy”, adds Karma Khazi. “In my teens, I was fascinated by most things art-related but felt intimidated walking in through the majority of gallery doors. The confines of gallery spaces don’t accommodate every individual, but they can be inspirational places. It is important, therefore, that prospective visionaries have the opportunity to encounter and engage with these works one way or another. If that means seeing ’em on the side of an otherwise uninspiring blank wall—that’s a result! Art made outdoors in the public arena ensures that future generations, whose families don’t visit galleries or have a masterpiece hanging over the sofa, aren’t deprived of the chance to encounter great art.”

So far, this battlefield has spanned from Margate, a British seaside enclave, to the facets of Afghanistan’s desolate infrastructure, with originators such as Banksy, whose Valentines Day Mascara, which inhabits one of the former’s numerous brick walls and Shamsia Hassani, along with her various artworks portraying Afghanistan’s country women in a patriarchal society, leading the charge in a fight that’s less about reclamation and more so for provocation; it’s from this perspective that American conservative political commentator Heather Mac Donald declared graffiti, in the New York Times, as something which is “always vandalism.” “By definition, it is committed without permission on another person’s property, in an adolescent display of entitlement,” she said. “Whether particular viewers find any given piece of graffiti artistically compelling is irrelevant. Graffiti’s most salient characteristic is that it is a crime.” Simultaneously, Rishi Sunak is also erecting barricades; the British prime minister has developed a battle plan to combat antisocial behaviour, which would see people who vandalise public spaces having to repair the damage they’ve effected within two days of being given an order. “Graffiti as its core is illegal”, points out Roger Gastman. “I am not going to argue with someone that this is art and should be legal anywhere it is or give us ten walls in the city to do it. That takes away from what it is. The nature of how it’s done and the energy of the streets is part of what adds to its magic. People have and always will associate graffiti with vandalism. But hey, some of the best art I ever saw was vandalism. How about you?”

“Engaging in graffiti art usually requires supportive criminality that assists the artist in painting. The most lucrative and convenient crimes include theft and drug trafficking. Spray paint, markers, and other accessories utilised to paint graffiti are expensive,” pointed out Camille Lannert in her research paper, The Perpetuation of Graffiti Art Subculture. “By stealing what they need or earning money from trafficking drugs to purchase what they need, graffiti artists can paint frequently and independently. The deviant lifestyles graffiti artists lead help perpetuate and support their art.”

Unintentional or not, it’s Gastman’s perspective that jumps into the crux of conversations which argue anonymity as this art form’s raison d’etre — by not being chalked up to an individual, it becomes not only associated with but the voice for many, with these, whether they belong to gardeners or accountants, store-clerks or engineers, bellowing at somebody who may be sitting on the toilet, as concentrated on in Karma Khazi’s upcoming SH!T SHOW retrospective which is gearing up to present observers with approximately 63 pieces of graffiti pulled from the messages scrawled across various toilet cubicles that he came across during a 250-pub crawl. To put it bluntly, the louder, wilder and thus more obnoxious, the better. “Graffiti is generally made from a place of true passion and integrity where the artist isn’t trying to make a few quid” points out Karma. “That’s special – in a world where we’re relentlessly sold to at every given opportunity. I’ve often referred to the back of toilet doors as ‘the final frontier of free speech,’ and I’d say the same goes for graffiti. SH!T SHOW is a physical demonstration that captures and connects these elements. Another artist, with an idea they love, going all out (compelled) to wholeheartedly represent a concept/identity. I’m not trying to make money off you. This is naturally connected to graffiti – as it’s all the same beautiful shit.”

“Through this project, I have learned that the impulse to express ourselves is just as present now as it’s ever been,” he continues. “I’ve also learned that our nation is far more optimistic than the global perception awards us. It’s a remarkable human instinct that has been around long before the considered ‘prominent originators.’ As long as people continue to live authentically, progress will continue to be made.”

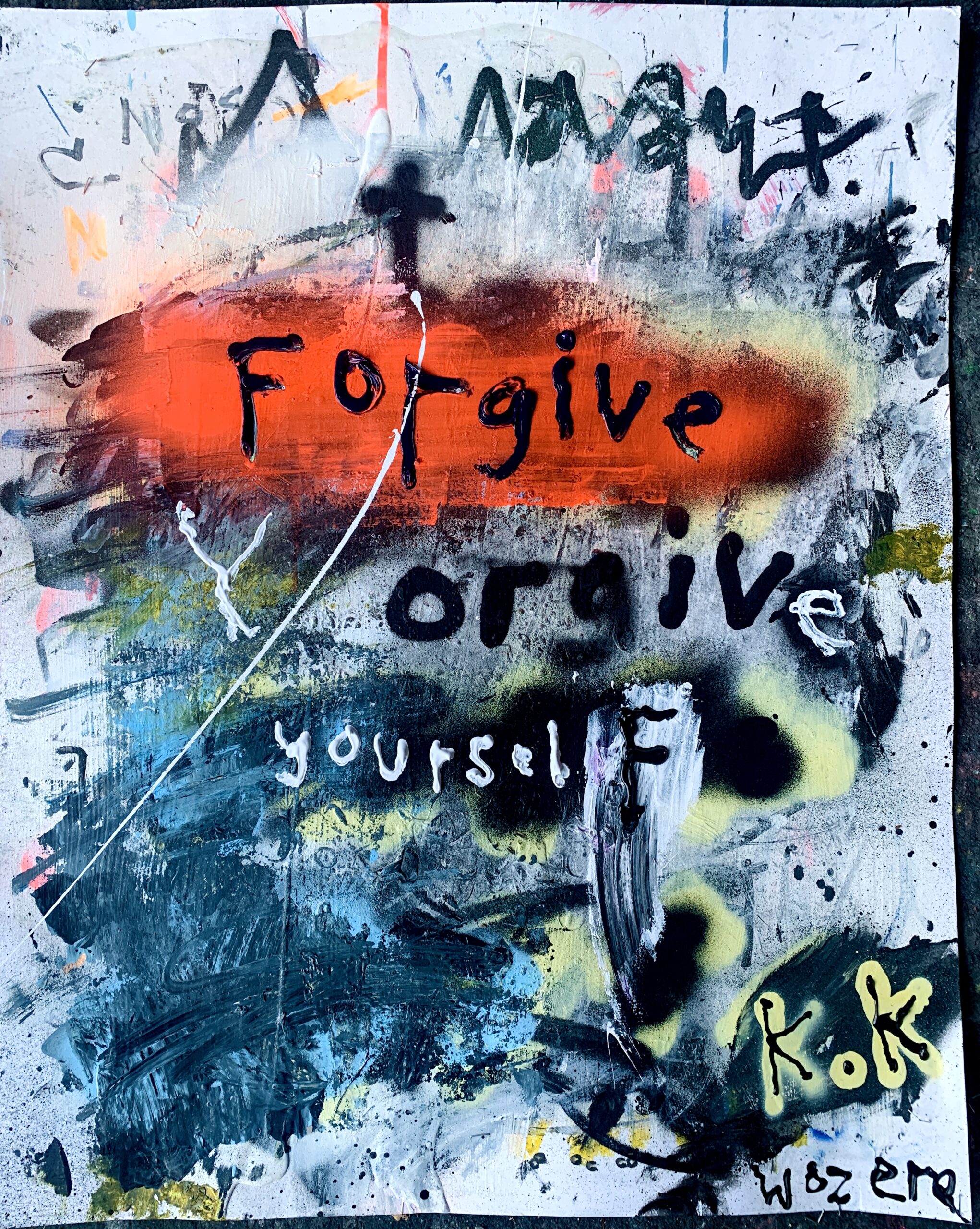

“For me, the best works are always about challenging our own belief systems whilst still visually offering some comfort. We like that as humans,” adds Samo White.

That’s where places such as Leake Street Arches come into the fray; this particular location, nestled underneath Waterloo, has served as a playground to originators including Swoon, Logan Hicks and now Marc Craig, who is doing a residency programme until April 2024. Needless to say, the street artist has a thought or two about the space — “Either end of the tunnel, there is this apparent line where you can’t go beyond. There’s a wall on the north end of the tunnel where, socially, it’s acceptable until the left as you go in, but it’s unacceptable as you go right when you come out, and there’s this constant battle between the energy that is Leake Street and the energy that is law and order, That for me, is one of the most interesting parts of the tunnel because the wall is completely covered and then a person comes along and paints it grey. When Banksy came in 2008 and created The Cans Festival, what he did wasn’t put the lid back on the box — once you open the box, you can try to put the lid back on. I spoke to the LCR official and said, ‘Have you ever given permission? Because everybody calls it the legal graffiti spot’ — they never gave permission, and nobody has given any permission.”

Written by Sabrina Roman