Belgian artist Berlinde De Bruyckere returns to Venice this year to present “City of Refuge III” at Abbazia di San Giorgio Maggiore. The exhibition is an official collateral event for the 60th Venice Biennale and runs until 24 November 2024.

This is the third iteration of her “City of Refuge” series, which originated last year with a show at La Commanderie de Peyrassol in Provence, France, followed by a second edition at the Diocesan Museum in Freising, Germany. While De Bruyckere hadn’t planned to do another exhibition in such quick succession, when she received an invite last year from Carmelo A Grasso – the director of the Benedicti Claustra Onlus monastery – she felt it was an offer she couldn’t refuse. “I’ve been coming to San Giorgio Maggiore Abbey for years. It’s packed with masterpieces of all times, and it’s always been a dream of mine to have an exhibition there to bring something that is relevant today into this long-standing dialogue between art and spirituality.”

The exhibition is shaped around the idea of art as a place of sanctuary and shelter, themes that feel especially relevant given current global issues. De Bruyckere expands: “I am heavily influenced by the world around me – the brutal images of war, the devastating consequences of climate change, the destruction of natural resources, the consequences of the pandemic. These human and natural catastrophes we encounter in newspapers every day are etched in my mind. I am a witness to society with a strong need to translate what I see into my work, to raise questions, open a discourse, ignite hope, perhaps, or provide some consolation. I try to capture both the brutality and the fragility of man and nature in my work. The current context determines how we read the work, but violence is of all times.”

The name of the show comes from a Nick Cave song. De Bruyckere explains: “The title ‘City of Refuge’ resonates with everything we’ve experienced on a global scale in the last years. The pounding repetition of the phrase ‘You better run’ is terrifyingly accurate and applicable to all of the catastrophic events we’ve been confronted with. But for me, it’s also the reference to the biblical cities of refuge; the duality that lies in the concept of these cities, how they encompass both the search for shelter and the danger, human cruelty and human kindness, something I think is as crucial for my work as for that of Nick Cave. His work has been an inspiration for me since the very start and has undoubtedly influenced my experience in art. Though we work in different fields, I think we both try to address the personal through the universal, taking inspiration from the classic stories, mythology, religion, and confronting those elements with the seemingly mundane, but equally intense shreds of everyday life.”

The show opens in the main church space, where three archangels are shrouded in blankets and installed on raised plinths, towering above visitors. Mirrors are placed behind the figures, connecting the works to each other through sightlines. These sculptures further develop the themes explored in her 2019 “Marsyas” works: “The casts of animal skins, unlike with the earlier ‘Marsyas’, are here fluidly draped over the human figure below, so that its head and shoulders stand out clearly, with pointed extensions that strengthen the suggestion of wings. The Arcangeli also recall the blanket figures I made in the nineties where the head and upper body of slightly hunched female figures are covered by a pile of blankets, simultaneously suggesting a scene of warmth and protection as well as deprivation and concealment. I added the mirror screens to the sculptural clusters of the Arcangeli to amplify and diffuse the experience of these angels. I didn’t want to present them as a single statue on a pedestal but as a presence lingering through space, appearing and dissolving as you walk along.”

In the sacristy, tree trunks cast in wax sit upon metal welding tables. This installation references De Bruyckere’s 2013 work for the Belgian pavilion, where a 17-meter-long tree trunk cast in wax was placed on pillows and bandaged with rags and blankets, suggesting the nurturing of a wounded body. She explains how this version differs: “Now eleven years later, in a growingly dystopian context, I chose to leave out the element of care, of human interaction. The tree installation in the sacristy is a post-apocalyptic setting, an image of ruin and ravage, gaining its element of rejuvenation, of life force, only from the power of the trees. This element of hope, despite the awareness of the horrors of the world and the understanding that we don’t seem to learn from our mistakes, is crucial to me. Just like the Salviati painting in the sacristy: the presentation of Jesus in the temple depicted as a gesture of great promise and hope and at the same time with the awareness of the painter of what Christ’s fate would be.”

Over the years, each artist who has been invited to exhibit at the church has been asked to create their own version of the choral manuscript used by the monks. De Bruyckere was apprehensive about this part of the commission, acknowledging, “I have probably made around 17 drawings in the past three years!” For her interpretation, she worked with thick blue paper that had been used as folders to store drawings and sewed these pages together with gold thread to create her own version of an illuminated manuscript.

In the galleries located behind the church, De Bruyckere presents wall vitrines containing casts of legs with flayed flesh, inspired by the story of St Benedict throwing himself into brambles to overcome his carnal temptations. She also presents floor sculptures of wax casts of animal skins piled on top of each other.

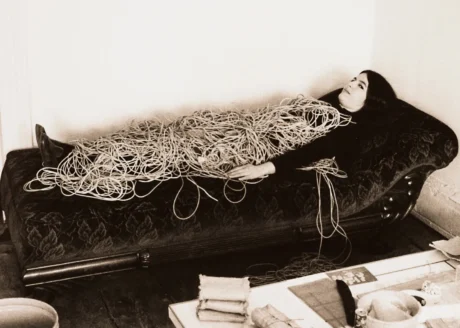

Despite being a well-known, respected, and revered contemporary artist, De Bruyckere is incredibly humble and acknowledges that some of the visitors to the space may be tourists who are simply coming to see the church and will be unaware of the exhibition taking place or familiar with her work. In order for these visitors to gain a better understanding of her process, she presents two vitrines with an assortment of source materials for her work in the final room of the exhibition. She also includes another archangel sculpture – “Liggende Arcangelo I” – which is lying down and is at eye-level height, allowing people to explore the work and the materials she uses up close.

De Bruyckere is reflective about returning to Venice to exhibit new work: “It’s always a special experience, and to have this opportunity after eleven years is extraordinary. A lot has happened in these eleven years; the world has changed, the art world has changed, and my experience as an artist has developed. I asked myself the same question when I started this project; what is different in what I want to achieve or convey.”

“I think my work for the Belgian pavilion was still a hopeful one; the fallen tree was surrounded with gestures of kindness, soft pillows, bandages made from old blankets in soft pink hues, and the light coming in from the cupola was filtered. There was an atmosphere of serenity, of quiet healing. Looking at the City of Refuge installation in the sacristy now, I think there we have a much more urgent situation, almost a catastrophe that is captured in a certain moment. Where is the hope in that image? I’m not sure it’s there. It’s a frozen image. I think of something that happened and wants our attention. It’s the sudden shock of the moment when we no longer know how to deal with the situation. Perhaps there is hope in the title City of Refuge: art as a refuge, a haven. Not a safe place in the sense that we need to soften the blow, be careful or restrict ourselves in any way, quite the opposite.”

Written by Holly Howe