Susan Meiselas, Dee and Lisa, Matt Street, Little Italy, New York 1976. Prince Street Girls, 1975-1990

At sixty-nine years old this is Susan Meiselas’s first institutional show. Her predilection for newsworthy subjects has seen her work more frequently categorized under the umbrella of photojournalism, however her process—developing bodies of work over long spans of time and integrating other archival documents into her presentation—allow her to adapt comfortably to an exhibition format.

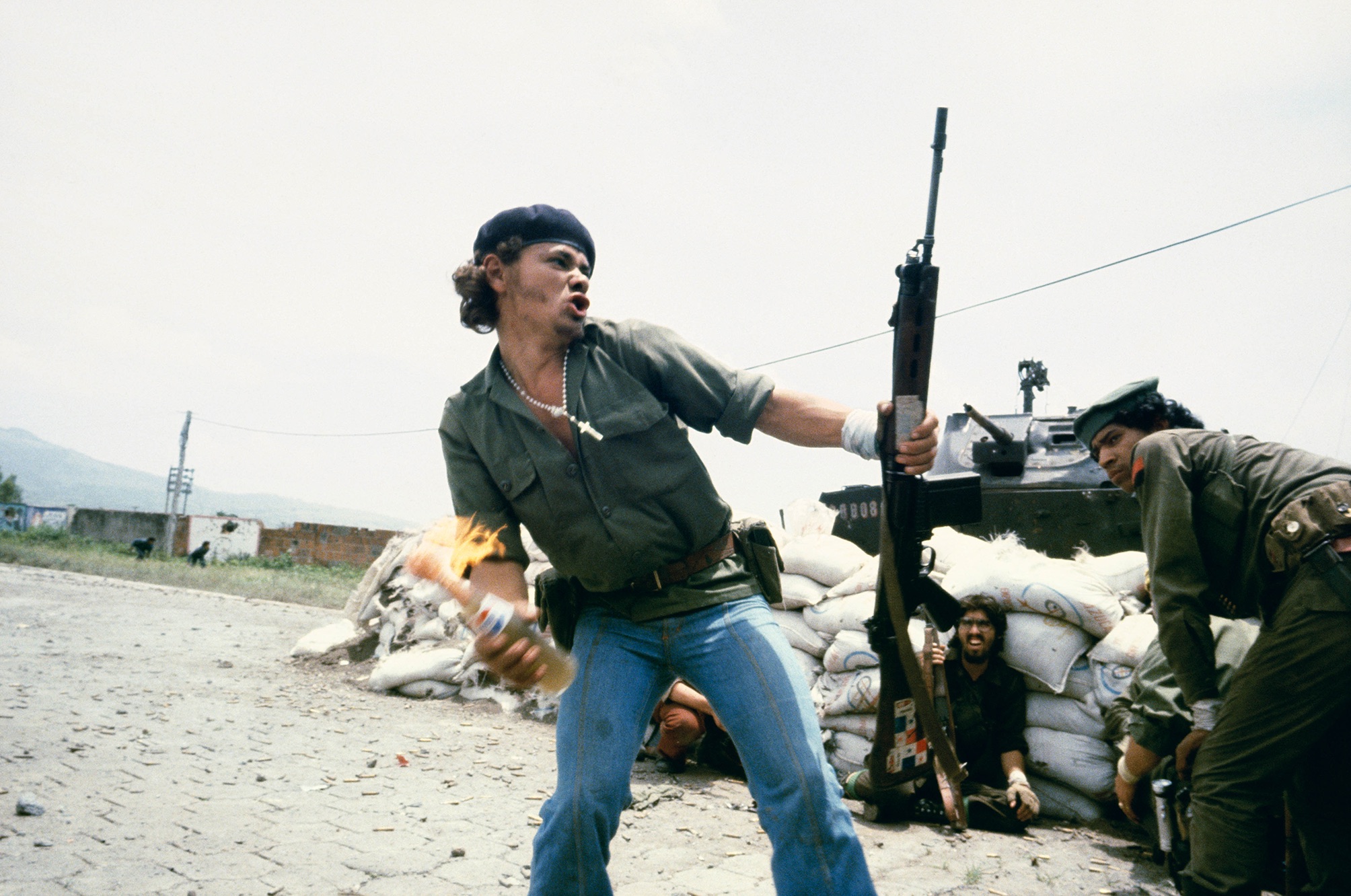

“We didn’t want to frame her as a photojournalist because the artistic process is so important in her work,” curator Pia Viewing tells me. Meiselas has been a Magnum photographer since 1976. Her first series modestly documented her surroundings: 44 Irving Street (1971) is a set of simple black and white photographs, portraits of those who lived in her boarding house. Yet even very early on, a methodology was in place: the subsequent Prince Street Girls (1975–1990) would unfold over a period of fifteen years, establishing an enduring relationship with its subjects, and bending the boundaries of the limited temporal frame captured by a single photographic snapshot. She went on to travel to Nicaragua and El Salvador mostly of her own volition without specific commissions, documenting the bloody wars that took place; she captured what was left in the wake of the genocidal waves of destruction in Kurdistan and at punctual moments took stock of the rapidly evolving sex industry.

She was warier than most, however, of the grave de-contextualization that could take place in photojournalism. The role of the reporter is one that implicates a conflicted ethical code. The exploitation of vulnerability, in the name of bringing light to some of the darkest social issues across the globe, is often justified in the voice it provides for those who would otherwise suffer in silence. Meiselas nonetheless appears to have a heightened sensibility to her nuanced role as documenter of people’s lives and histories; the audio and written testimonies that accompany each piece, the general release forms that are presented alongside the works and the sustained relationships that she establishes with her subjects attest to an overwhelming desire for the most profound transparency.

Each of her series starts off as a photo book, not least because of the difficulty of diffusion in the pre-internet age, but also as a means of maintaining a degree of agency in the way in which her images are presented, anchoring them firmly to a sprawling and detailed context that may otherwise be eroded when translated into press clippings. The room playing host to her series on the destruction of Kurdistan reads almost like a furiously detailed school project with a surprisingly crude Powerpoint presentation alongside maps, letters, photographs, tickets, diaries and short films, all sprawled across the space with an almost childlike appeal for recognition of the due diligence that went into this body of work.

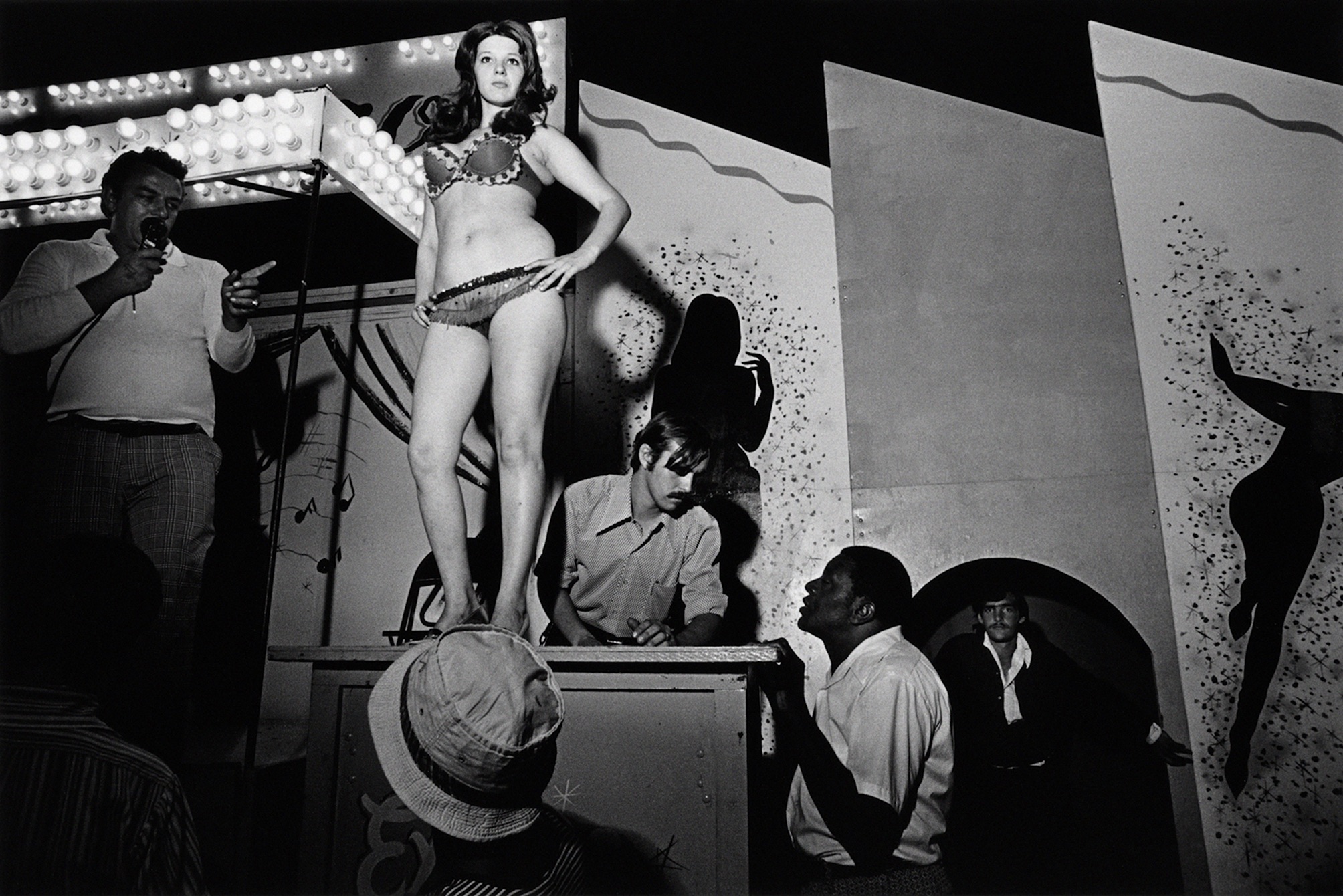

This transparency is a fundamental tenet of Meiselas’ political project, if it can be called that. That is to say, her means of working is to expose a subject matter in its plainest form. Without naïvely celebrating the perceived agency of the carnival strippers that she photographed, the eponymous series, spanning three summers from 1972-5, challenged the dogma of the prevailing brand of second-wave feminism. It did so simply by letting these women speak for themselves, alongside their bosses and their punters. If a photograph can communicate only one fragment of a single perspective, Meiselas works tirelessly to broaden the frame.

The passage of time is felt keenly across Meiselas’s oeuvre, highlighted maybe most presciently by the two series on sex workers that bookend the portion of her career on display in this show. In the first, a great furl of black pubic hair unfolds down the stomach of one of the carnival strippers in a New England fair, while another stands with her bikini bottoms bunched up between her legs, an unsightly scar sat above the top seam; girls loop their arms around one another as men and teenagers jeers and leer from a distance. The power balance nonetheless feels somewhat close to equilibrium, the women fragile in their nudity yet literally elevated by the wooden platform and crates that separate them from the rubbernecking crowd, bound as one by their sweat and their gaze. Fast-forward to 1995 New York, where the slick-bodied mistresses of Pandora’s Box sex club slide across a video screen, clad in buckled leather and spiky shoes. Here, the professionalization and the compartmentalization of the sex industry is felt acutely in the juxtaposition of both sets of images.

Meiselas again passes no judgement, adopting instead an ethnographic stance as she wonders what psychological therapy such practices respond to. This theme of violence navigates a precarious path in this exhibition. It isn’t immediately obvious; the venerating impulse of the retrospective format often uneasily eclipses the complex reflections on violence that are woven across her oeuvre.

Yet this precarity lies in the curatorial contortions that must be arranged so as to build a mosaic of her work which draws a tacit line between the violence of war, so prevalent in her photographs of the 80s and 90s, and the depth and complexity of the sadomasochistic relationships documented in the Pandora’s Box sex club around the same time. This takes place all the while avoiding any conflation of such consenting sexual partnerships with one particularly sparse series centred on female refuges.

There is much that makes Meiselas’s oeuvre cohesive, not least her sense of social responsibility that underpins not only her subject matter but also her careful methodology. However, the most complex question that runs through this exhibition may be articulated as such: how we can take stock of the transference of violence in different global contexts? It is a nuanced if not contentious gesture, yet the question is left open. What links consensual violence, solicited as a means of feeling intimacy, with the rabid violence of warfare that looks to raze, abase and divide?

All images © Susan Meiselas Magnum Photos