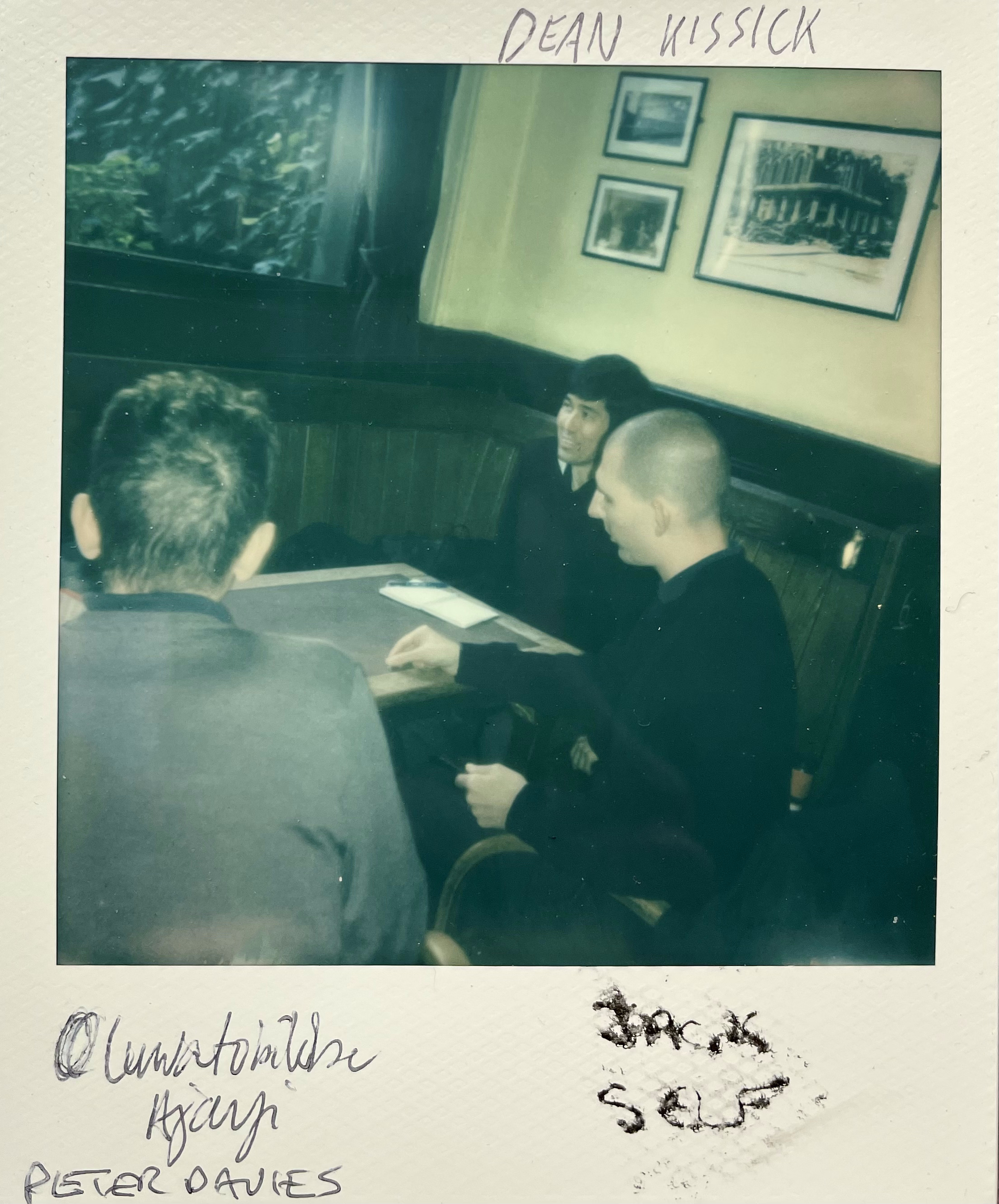

The context of this conversation reads like a bad joke. An architect, an artist, and a critic walk into a bar. On a sunny morning in January, Jack Self, Peter Davies, and Dean Kissick met at The Approach Tavern to discuss, not Kissick’s now infamous Harper’s cover story: ‘The Painted Protest: How politics destroyed contemporary art,’ but the state of contemporary art in London.

But why bring Jack, Peter, and Dean together? Peter is a painter and lecturer at Slade School of Fine Art and a stalwart supporter of London’s young gallery circuit. Jack is an architect and Editor-in-Chief of the Real Review—a London-based magazine about “what it means to live today”—skilled in tracking and naming patterns of cultural production. Dean, an art critic, cultural writer, and author of the piece that inspired the gathering, has recently returned to London after a decade in New York.

As far as Dean’s article goes, I’m generally weary about a critique levelled at the margins. Especially when the blow seems to come from outside. There seems an infinite pool of patience afforded to the canonisation of whiteness that evaporates when those on the margins attempt to enter the fore. However, my intention was not to stage a rebuttal against Kissick’s polemic, but to speak to the cultural context of London, grounding his concerns in our observations of the city we all share. What occurred was a delightfully meandering conversation that ranged from the emerging gallery scene to Luigi Mangione.

Oluwatobiloba Ajayi: I wanted to start by talking about London more broadly, how do you see the current role of London as a center for contemporary art? How has that shifted over the years?

Jack Self: The way I think about everything is always an exchange between the macro, impersonal, long-term, strategic, and data-driven, and how that matches up with lived experience or what you see in the streets around you. I think the immediate effect of Brexit was to reorient London away from Europe. It used to be a metropolitan capital filled with Europeans and was a centre for cultural production in Europe. Post-Brexit, that’s not at all the case. London has reoriented towards what I would describe as the African diaspora, and so the medium-term effect of Brexit has been for London to start to engage more with its history as an imperial capital and its legacy of Empire and colonization.

The statistics bear this out. In about fifteen years, London will become a non-white majority city. The demographic projections are 36% Black, 30% White, 30% Asian. That will be the first time it has been a non-white majority city, but it’s not just that the Black population is increasing, the diversity of Black communities is also increasing. Historically, London’s Black communities have been almost entirely Caribbean, Ghanaian, and Nigerian, but for many reasons, including climate change, we’re seeing those populations diversify across the Sahel, so Mali, Niger, Chad, Ethiopia, Sudan, and so on. I think that’s an amazing direction that the city is going in. You already feel that.

I was just thinking about the institutional shows that I really liked last year, and all of my top five were by Black artists. It’s not that they were being selected on the basis of their identity. It was on the basis of the work that they were doing, and they’re all very different. Last year I liked Aria Dean at the ICA, Rhea Dillon and Alvaro Barrington at the Tate, Hew Locke at the British Museum, and John Akomfrah in Venice was also great. I think I would argue that London is the global capital of Black excellence.

Dean Kissick: That is a good interpretation because it’s not one I’ve heard before. I think the general take on London—and I’m talking more in a commercial sense here, than an institutional sense—would be that Britain has pivoted away from Europe, and that London has lost its place at the centre of the art world. That’s said all the time. But I haven’t heard the second part of the argument, which kind of suggests it is a positive thing, suggests that this has been an exciting turn, it’s opened up space for something new, something different.

The general take is that London used to be the centre of the European art world. It certainly was when I left around a decade ago, and that now, it’s Paris. There has been a shift in power from London to Paris in art over the past decade. I went to Paris a month or two ago, and I went to see the Bourse. It was the first time I’ve ever been there, and I saw the new financial art world powerhouse that has been built in Paris, and it’s very impressive. A friend who was on the circuit said that the Paris fair is now where you have the real glamour and power. That whole week is spectacular now. Those institutions in Paris have a lot more money, there are more privately funded institutions, which didn’t used to be the case. London has always been a part of the African diaspora, but I like the thought of it as a new powerhouse, a new kind of mega-hub.

JS: Maybe I would add one more thing to that, which is that London is the only city in Europe, as far as I’m aware, that is getting younger over time. So, the mean age in London at the moment is about 32, and the mean age in 2040, when it becomes a non-white majority, will be 27. Weirdly, the reason why that’s occurring is because it’s too expensive to live in London once you reach an age at which you would like to have a family. So, there’s a kind of demographic exodus of everyone over 32. But the effect of that is the youth culture in London at the moment is extremely vibrant and extremely rich, but, at least in my experience of living here for quite some time, it’s never been harder to be young in London. So, the sacrifices and the difficulty of being involved in the cultural sector as a young person are extreme today. It’s a very mixed picture. I think all the things we’re saying are true, it’s a total collapse of our economic and cultural capital. It’s a complete pivot away into an entirely different history of Britain, which is producing a focus on a completely different type of art, which I think is great. And it’s super vibrant if you’re young, but it’s also extremely shitty to be here if you’re young.

Peter Davies: It is so interesting for me listening to both of you because the position from which you’re looking is so different to mine. You’ve both got different overviews of things or views from elsewhere, but I feel kind of embedded within a situation here. So perhaps I haven’t got a sense of objectivity. I’ve got a more perceptual notion. I think I’m more involved with a sector of the art world which isn’t generating huge amounts of money, and also isn’t being represented within institutions on the whole. My perspective is, much more coming from—I’m an artist, I’m in my 50s, I’ve taught in an art school for more than twenty years.

Through teaching, lots of former students started to exhibit, and this was around the time that the lockdown was lifted. I think we’re in a historic moment in London right now for emerging contemporary art. It has always existed, but it’s not quite in the same way that it does now. After the pandemic, quite a number of significant new emerging art galleries, all commercial galleries, opened. It sort of defies belief in the face of what you’ve just explained. It almost doesn’t make sense. How can this be, with the cost of living? These galleries like Ginny on Frederick, Brunette Coleman, Rose Easton, a. SQUIRE, Ilenia, Hot Wheels, some of whom were included in Frieze this year. They’re creating a kind of moment and a community. The only comparable thing I’ve experienced was the YBA period, but the YBA period was very different in numerous ways. It wasn’t a sense of community; it was a clique, and it wasn’t a friendly, welcoming, and inclusive environment. It was very elitist and competitive in a particular way, and I feel that the community now—there is a lot of competition, but there’s much more of a sense of mutual support, which is something I find really inspiring and hopeful. I think that, in watching this community grow over the last two or three years, and seeing the things which people are beginning to achieve, I can only see it being looked back upon as an important moment within contemporary fine art in London.

When I look at this younger generation, who will frequently put on a show for a night, you know they’ll do a proper group show with all the logistics of organizing that and it would just be open for the private view and that’s not weird. So, for them like four or five days in a temporary space with a huge number of people seeing the work is something that they take very seriously. I think they’re reimagining the possibility of an art space in a way that my generation and maybe the generation in between didn’t.

OA: I guess there’s kind of two things happening here. There’s the institutional shows and the scene around these emerging galleries. I’m suspicious of these institutional shows about race and figuration. I think that’s why the first time I read Dean’s article, probably when I was reading most generously, I shared the frustration with a kind of lazy identity-based curatorial impulse. It reminded me of shows like Entangled Pasts at the RA, where I was moving through the exhibition in awe of these works by Frank Bowling, Betye Saar, and Ellen Gallagher, works I’d never had the chance to see before, but the curatorial framework, or the packaging, felt flattening.

Alternatively, when I saw your show this summer Peter, On Feeling at The Approach Gallery. It felt like a rally against the idea that identity has to be foregrounded curatorially and intellectualised through a theoretical lens. It was very much about an intuitive emotional response to these works in relation to themselves. This feels related to Dean’s polemic. I’m curious to hear how you interpret the stakes Dean raised in his article, and how these might resonate in the London context?

JS: When I read Dean’s text, it resonated with me, and it also clarified a sort of subliminal emotion that I’ve had a lot when I go and see shows. In order to understand this, perhaps I would give two different definitions of diversity and inclusivity. Diversity, to me, is about box ticking: is there someone in the room who’s queer? Is there someone in the room who’s indigenous? Inclusivity is to say, “Well, what were the structural conditions which might have prevented there being a diverse group of people in the room to begin with?” And certainly, I think you can feel the difference in some way. So, I think your point about the RA is spot on. It felt somehow—I don’t want to say cynical or opportunistic, but I hate to be this way, but you can just feel it.

It is the case that many of these big institutions, commercial galleries, and large institutions have been guilty of this appropriation and expropriation of all forms of work. Not just by people who are not white, but across the board. One thing I would say about London, in London’s defence, is that—if I think about the people I know who are a part of the senior leadership at the ICA, or Tate, or increasingly also the board of the British Museum—the makeup has changed. I think of the work of someone like Ekow Eshun and the role that he plays across so many institutions in London. I think the structural reforms, in terms of who makes the decisions within institutions, have been changing really slowly over probably twenty years. I don’t think it’s like a George Floyd knee-jerk reaction which I think is often what you feel in those types of shows that you’re describing.

DK: You mentioned packaging. I think that’s the key thing—that’s what I was writing about a lot in this essay, and thinking about as well. Really, most of what we’re talking about is curation. It’s decisions made by curators on how to package and frame and come up with themes for shows, for the biggest exhibitions in the world. And likewise, it’s decisions made by gallerists for how they frame their shows but also how they sell work. It’s a lot about packaging; how people curate shows and how people write press releases, and it comes back to critics, how they review shows and what people talk about. And I think a lot of that is very cynical. It’s interesting, you know, I think the five shows you mentioned at the beginning, Jack, I haven’t seen one of these shows. But I think they’re all solo shows, although perhaps Hew’s show is kind of a curatorial project led by Hew Locke.

So, you’re talking about individual projects by Black artists, which is a different thing from group shows of underrepresented artists and how those things are framed. And from the response I’ve had to this piece, much of which is very critical of me, of course, I also don’t feel a great deal of warmth or support for institutional curating at the moment. There’s kind of a pretty widespread contempt or frustration with a lot of what’s happening at the high level of institutional curating.

It’s interesting when you talk about galleries, because you’re talking about something that’s happening in London, which I don’t think is really happening in New York, an exciting development which is really being led by galleries working closely with artists, or with their wider community.

PD: I mean, I remember talking to someone about 15 years ago, who’d done the curating course at the Royal College and said “He wanted to be a curator, but he couldn’t get a curating job, so it was easier to start a small gallery.” It didn’t really work out, but I remember that stuck in my mind, and in a way, the thing I found interesting about these new galleries in London has been their curatorial approach.

I feel on the one hand always frustrated at institutions, but on the other hand I’m not even that bothered by what they’re doing because there’s other stuff going on. I think when I curated the show [at The Approach], I was very conscious that I’m a middle-aged, white, heterosexual man. I’m the patriarchy. So, I was not the person to curate a show of emerging young artists, except that the relationship I had to this particular gallery meant that I felt I could welcome people who hadn’t had the opportunity to show here before. I remember standing in the main space—there were seven people in that space, two of whom had been born in the UK, one of whom is Iranian and Turkish and had grown up in Turkey, and the other is Black British who grew up in Essex, and that just seemed so exciting. The fact that not everyone in that show had been to art school, but most of these people had come to London to study art, or be an artist, and people still want to do that. That’s something that continues to amaze me. In reading your article Dean, I had this real sense of frustration on your part, at something. Because of the art I’m excited by, I don’t share that frustration, I have a much greater kind of optimism.

OA: What makes a good show?

PD: How do we judge art when it’s so subjective? When we’re talking about institutions, they’ve always been frustrating and disappointing for as long as I can remember. They always seem like they’re not listening; they all seem like they haven’t looked.

JS: Personally, I prefer single artist shows because I like to see the perspective of the artist. And that’s because my definition of good art is both something which resonates with me personally, but also has a kind of transcendent or sublime quality, right? So, I’m very suspicious of group shows in which, as we know from the history of Harald Szeemann, there’s a kind of automatic appropriation and categorization of artists in any group show, which is forced.

It is unquestionably the case that that art was the centre of cultural production in most western societies in the year 2000 and if you look at what was occurring at that time, it was people like Damien Hirst, Olafur Eliasson, Jeff Koons, and so on. They, in some ways, represented the centre of cultural discourse. My argument would be that throughout the 2000s and early 2010s the art world became financialized, and it became very commercialized, which led to a de-risking process in order to sell works to people who were from a non-western European perspective. I’m thinking particularly of the rise of Russian and Chinese investors, who are mainly —I don’t mean to be derogatory about this— many of the new collectors which arose during the 2000s and 2010s as a product of capital controls within other countries. So, they were looking for places to move their money outside, and that involved the acquisition, as they say in the City of London, of S.W.A.G: silver, wine, art and gold.

So you have this kind of hyper-production of capital which is looking for somewhere to go. And of course, it cannot be politically contentious. It needs to be like a kind of Antony Gormley, right? And ideally, it should be reproducible, like an Antony Gormley where, you know, you’ve got your Maserati, and your neighbour’s got the Maserati, and you’ve both got your Anthony Gormleys, and everyone’s happy, right? The problem with that is it de-risks the art process at the high level, because you can’t take risks, so you have to produce commodities. And that meant that, over time, the trickle-down effect weakened art as the centre of cultural production.

PD: Your perception of structure is fascinating.

DK: I think about this a lot, and I agree with this materialist analysis. I think over-financialization of art has been a disaster for the art world. That’s been far more of a disaster than the cynical use of political gestures.

JS: There is certainly a strong spirit in all of the reactions that I’ve seen to your piece, but it’s not controversial to say that we live in a time in which the status quo is being rejected broadly. You see it in the rejection of the political status quo, you see it across the board. People are pissed off about how things have ended up. The last time that I felt such a strong social desire for real meaningful change was in 2011. And that kick-started a chain of civil movements. Living in London in 2011, I was caught up in the August riots, I was involved in the Occupy Movement at the London stock exchange. Then, you know, after Occupy, you have BLM, one, two, and three, Extinction Rebellion, #Time’s Up, and Me Too. So, you have this series of rolling civil rights movements. Certainly, post-pandemic, it’s only now, really, since 2023, that I started to feel that there’s a real extreme desire again to explore quite a different direction in society.

DK: Yeah, I think so. It feels like a moment of change. There was a period which I’d date from 2016 to present or so, Brexit, Trump’s election, and it does feel to me like we entered a new era. Who knows what it will be, but I was in New York for the U.S. election, and the lack of reaction to it was so palpably different from 2016 and 2020.

JS: The moment of change for me was when the Titan sub imploded and killed all those rich people, and I saw the incredible, extreme vindictiveness in the response, the malevolence of that. And then you look at something like the alleged murder by Luigi Mangione, and the kind of cult of Luigi which has come out of this. The tolerance for, you know, the things I highlighted last year, in terms of tipping us into a new era of normalized ultra-violence, are the genocide in Gaza, the [attempted] assassination of Trump and Luigi Mangione’s alleged murder of the United Healthcare. The different responses to all of those, and the way those are taken collectively, suggests to me that, not only are we entering quite a different relationship with contemporary culture, but that this dissatisfaction with the status quo, which I think for the last ten years has been, like, “Let’s knit pink hats with ears on them.” I think this idea of peaceful violence protest as achieving social change might be at the brink of changing quite radically. I see that as being an important trend. I don’t know how that will play out within the art world, but I expect to see more violence generally in culture in coming years.

OA: My last question was an attempt to end on a note of optimism. Is there anything that you’re excited about and looking forward to in the coming year?

PD: Yeah, I’m really excited. [Laughter] I hope that the London emerging gallery scene starts to get more internationally recognized. I hope more galleries open, we need more collectors in London. There’s some shows I’m really looking forward to Alex Margo Arden at Auto Italia, which is just around the corner. Kiki Xuebing Wang and Raque Ford at Ginny on Frederick, Mohammed Z. Rahman at Peer, Christina Kimeze at South London Gallery, Jake Grewal at Studio Voltaire, and Condo, which happens next weekend. I love Condo.

DK: Great, I want to see those shows. I’m not familiar with any of those artists you just named, which is exciting.

JS: 2025 feels to me like the first year in half a decade that I can plan, and I know that God laughs at our plans, but I’m a Godless man. So, I have made some plans, and I’m now going to try and execute against them. That feeling of new beginnings and of new opportunities obviously stands very much at odds with a general environment which is more precarious and there are greater levels of danger and threat and risk to everything we do. But, nonetheless, I feel quite hopeful and positive about the future in general.

Thank you to The Approach Tavern for hosting us, and thank you to The Approach Gallery for facilitating with the venue.

Words by Oluwatobiloba Ajayi