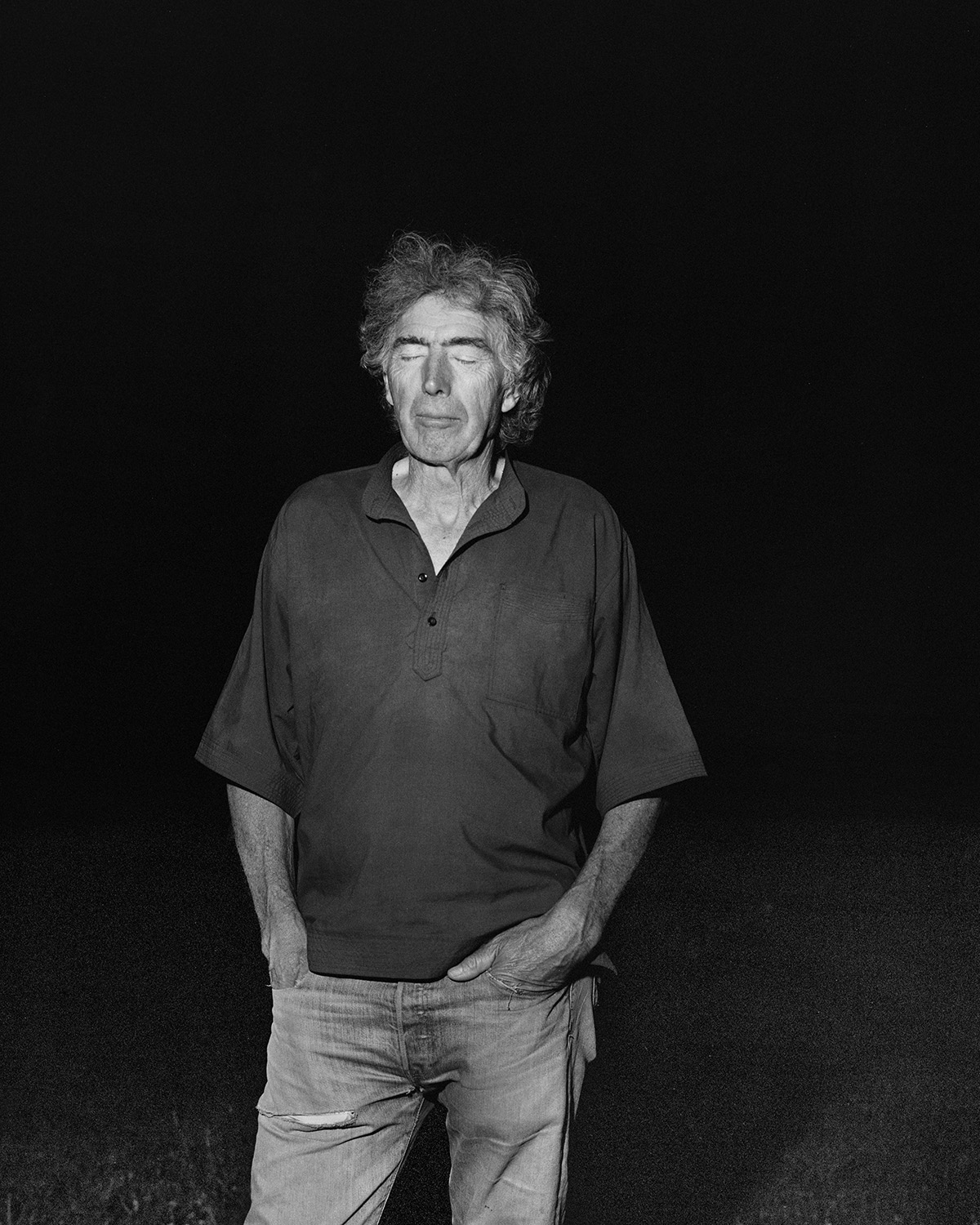

Yvan, Paris, France, 2017

On the night of 23 April 1993, somewhere in France, writer and puzzle maker Régis Hauser buried a bronze copy of la chouette d’or (“The Golden Owl”), a 25cm-tall statuette of an owl, made of gold and silver with a diamond encrusted on its head.

The same year (under the pseudonym Max Valentin) Hauser published On The Trail Of The Golden Owl, a book of 11 riddles, each presented with a matching painting by the owl’s sculptor, Michel Becker. A quarter of a century has come and gone since the burial, with no sign of the owl. Whoever finds the bronze copy wins the gold original, currently guarded by Becker. But with Hauser’s passing in 2009, the secret whereabouts of the prize died with him.

It’s a compelling tale, one which drew British photographer Emily Graham to the crisscrossed trails of the Golden Owl. The Blindest Man is her first monograph, the product of three years spent focussing not the prize itself, but those still pursuing it, hunters referred to as “chouetteurs.”

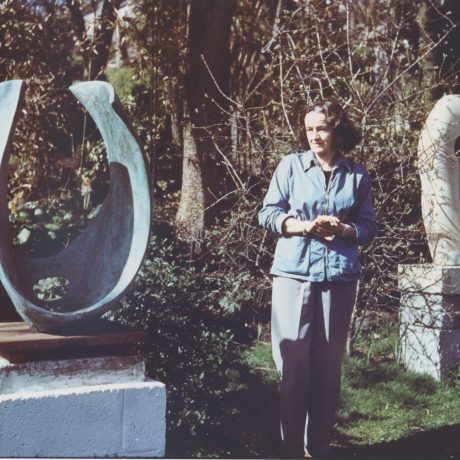

Disguise, 2017

The cold trail still calls out to sleuths, hobbyists, and eccentrics, all set on ending one of the world’s longest-running treasure hunts. In Graham’s book the images teeter between anthropological documentary and enigmatic tableau, as she follows unsuccessful trails and the chouetteurs who chase them.

She presents an eerie, awry world, one in which Hauser created something deeply enigmatic: a rural oddity reminiscent of the 1973 film The Wicker Man or the 1967 series The Prisoner. Something is amiss in the French countryside. Staircases lead to nowhere, a dismantled plane sits above old tires, a lone peacock looks out from a hill.

The Blindest Man

makes the reader search for signs where there may be none, interpreting each mark, object, symbol and subject as a possible lead. It becomes a game in the ways of seeing, the reader scrambling for any hint of logic or instruction. One becomes a temporary chouetteur, squinting eyes, hoping to strike gold. Graham makes you question everything: split up and look for clues.

Graham’s portraits of hunters living life by the golden trail reflect the abstract curiosity of her landscapes. There is a determination behind these chouetteurs. Wrapped up in secrecy and esotericism, their gaze rarely meets the camera. They seem to have other, more pressing issues on their minds, living in an increasingly complex web of debate, interpretations, and theories. Maps are drawn and redrawn, arrows lead to nothing. X doesn’t mark the spot.

“A quarter of a century has come and gone since the burial, with no sign of the owl. Whoever finds the bronze copy wins the gold original”

Each of the 11 riddles and paintings in On The Trail Of The Golden Owl have been dissected into oblivion, with fresh theories still arising. It reminds one of tight-knit internet communities, networks of like-minded people separated by continents, glued together by a singular, essential commonality. It feels like a collective mania, reminiscent of the social explosion that was the 2016 summer of Pokémon Go, or the communal buzz of a long-anticipated concert. Internet sleuthing, chatrooms, and specialist forums were all in their infancy when the owl was buried, but now this treasure hunt can be seen as a blueprint for the collective obsessions found in online communities.

Competition, collaboration, isolation and intrigue are all at play in The Blindest Man. The high value of the owl (estimated at €150,000 when it was buried in 1993, and worth much much more now) encourages isolation and independence among its pursuers, yet many in the community share notes freely, and argue endlessly. They become one collective, one entity on the hunt.

“The high value of the owl encourages isolation and independence among its pursuers, yet many in the community share notes freely, and argue endlessly”

In a twisted way, you find yourself hoping that they never find the owl. What happens once it is found? Somebody will get rich, and this community of chouetteurs, which has grown into something sprawling, far larger than Hauser ever imagined, will cease to exist. The hunt exists on the spectrum between hobby and obsession, like allotments, bird watching, knitting clubs and dominoes in the park.

Franck at Chouette Fete, Carignan, France, 2017

The act of a hobby, or more accurately its pursuit, outweighs the final product, the prize of the win. It is about the journey, the connection, the solving of the puzzle and the spark of a new lead. It’s easy to imagine the people who have met along these mysterious circuits; the inside jokes, the inflated stories, crackpot theories told over campfires and dinner tables.

“Each of the 11 riddles and paintings in On The Trail Of The Golden Owl online pharmacy zovirax buy with best prices today in the USA have been dissected into oblivion, with fresh theories still arising”

Graham’s work explores the elusive nature of the search, the indomitable human need to know. The Blindest Man is an apt title when imagining this nebulous community of chouetteurs, close to three decades in and not a hint of gold to be seen. What if the whole hunt is nothing but the blind leading the blind? What keeps the search going? The need to know, the need to be first, or the need to not give up?

In a 1996 interview, owl mastermind Hauser said that “If all the searchers put all their knowledge together, the owl would be found in… two hours.” This echoes through Graham’s images, the almost tragic thought that maybe the underlying competitive nature of the hunt, the desire to retreat and not to share, will keep the owl buried. Regardless, the chouetteurs persist. As long as the owl remains hidden, this world, this community, will still be right there, wandering across the nation. Looking, searching, sharing.

Isaac Huxtable is a writer and works as programme assistant at The Photographers’ Gallery, London

The Blindest Man by Emily Graham is available to pre-order now (Void)