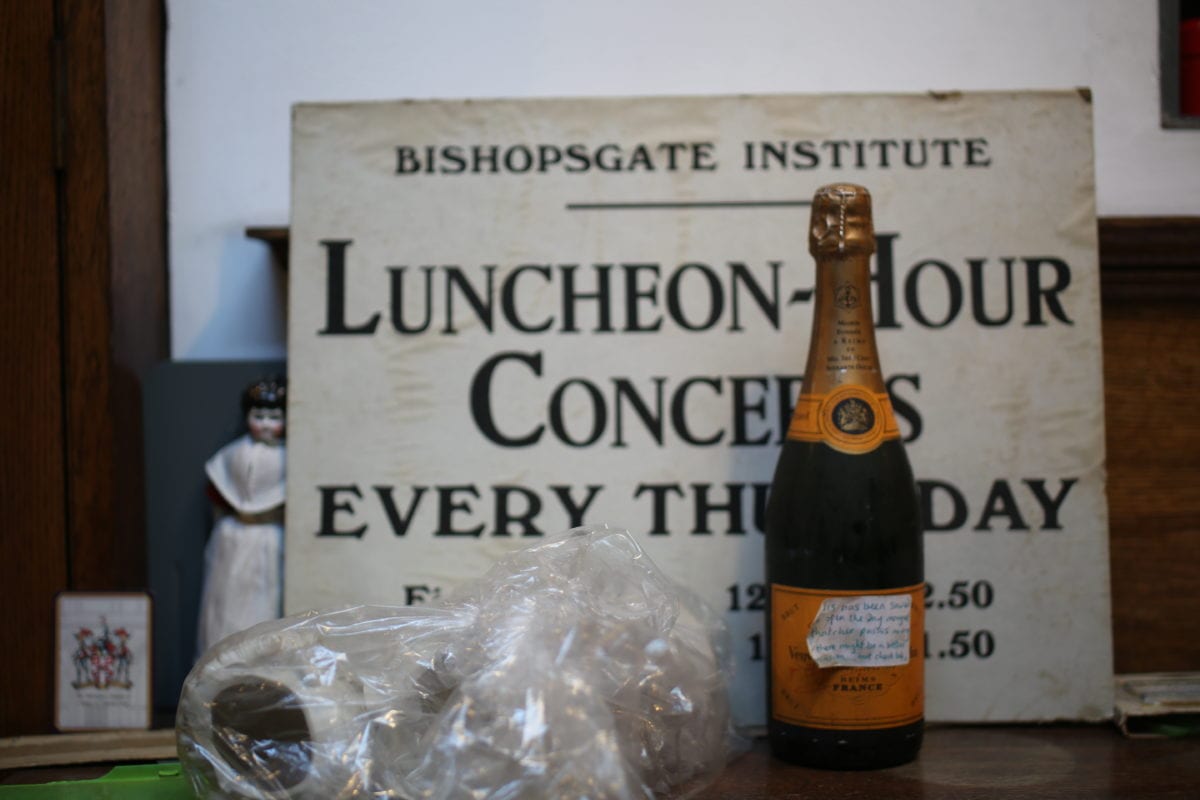

Unless you’re in the know—and notwithstanding the rainbow flag that adorns the building’s exterior—there’s little to indicate what strange and brilliant treasures lay in the archives of the Bishopsgate Institute Library and Archive collections. The building, a stone’s throw from Liverpool Street Station in east London, opened in 1895, and until fairly recently was best known for its collections archiving the history of London and the “labour, co-operative, freethought and humanist movement.”

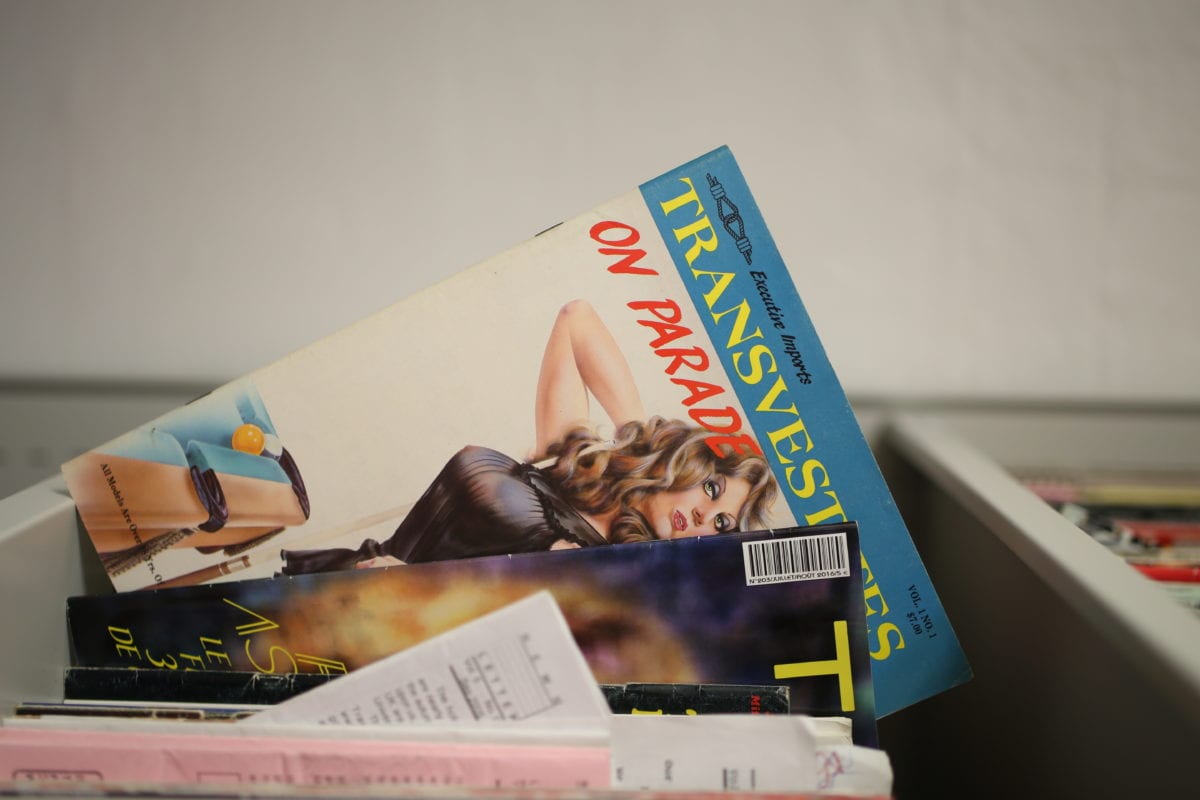

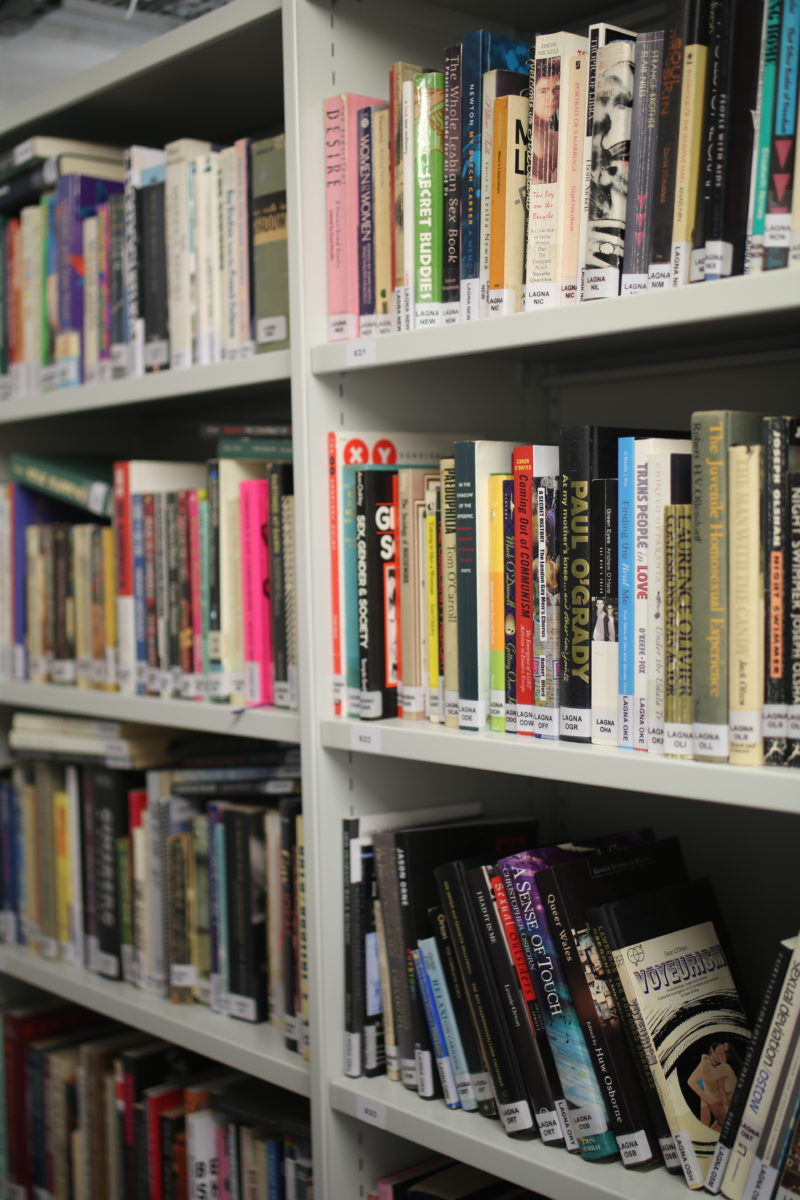

In recent years, however, things have taken a deliciously racier turn, thanks in no small part to library and archives manager Stefan Dickers—a brilliantly dynamic, passionate and inquisitive chap who has gently shifted the focus toward the archiving of queer histories, gay culture, the leather and rubber scenes, and “alternative sexualities such as BDSM, kink and transvestism.”

The fact that Bishopsgate Institute is a completely independent charitable foundation (it was founded from money left by a church) means it can be “a bit edgier,” says Dickers. “They’re very supportive of creating an identity for the institute, so we can take a few more risks. That’s why there’s a big fuck-off rainbow flag outside.”

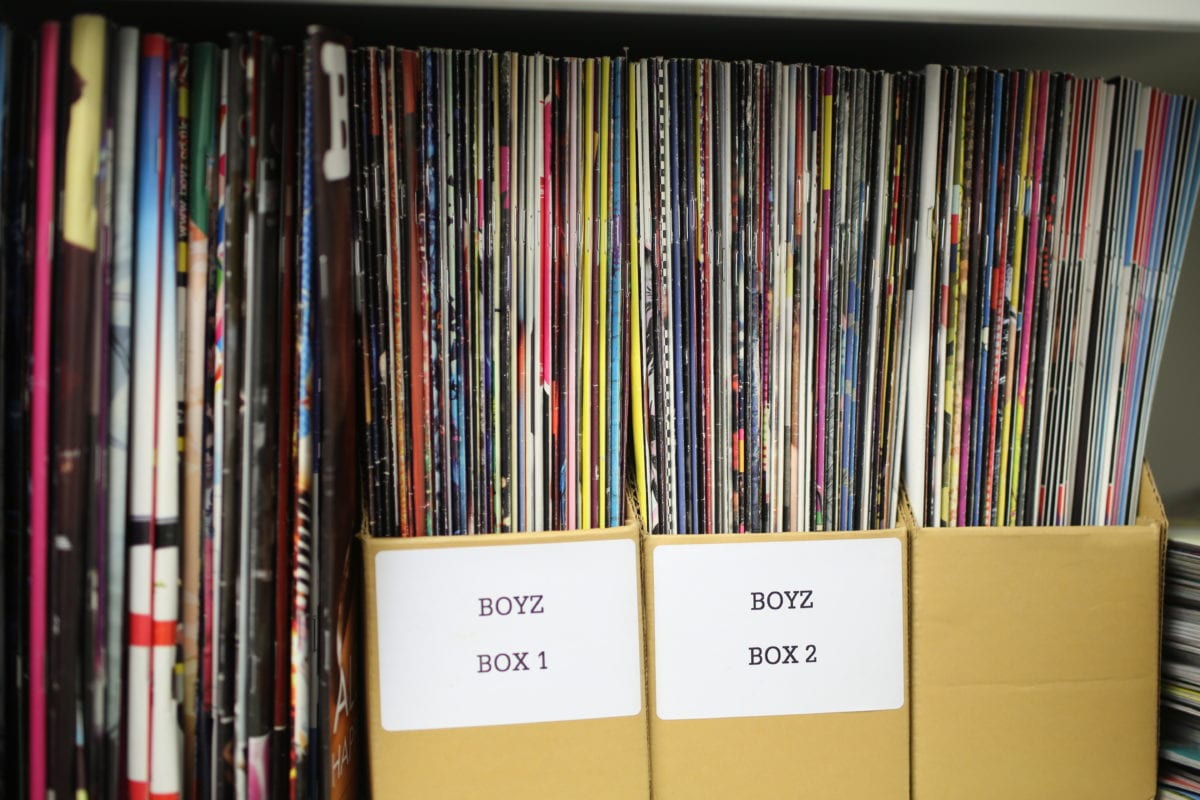

Dickers says the collection as it is now started to take shape in 2011, and it was in 2016 that the sexuality side of things really took off. “It’s been very much a learning experience,” he says, in terms of what to collect and record. With the LGBT artefacts and print materials, people often approach the archive directly, although Dickers will on occasion seek out those he knows to have particularly relevant collections.

“We do as much as we can to get it out there and make it alive and let it inspire people”

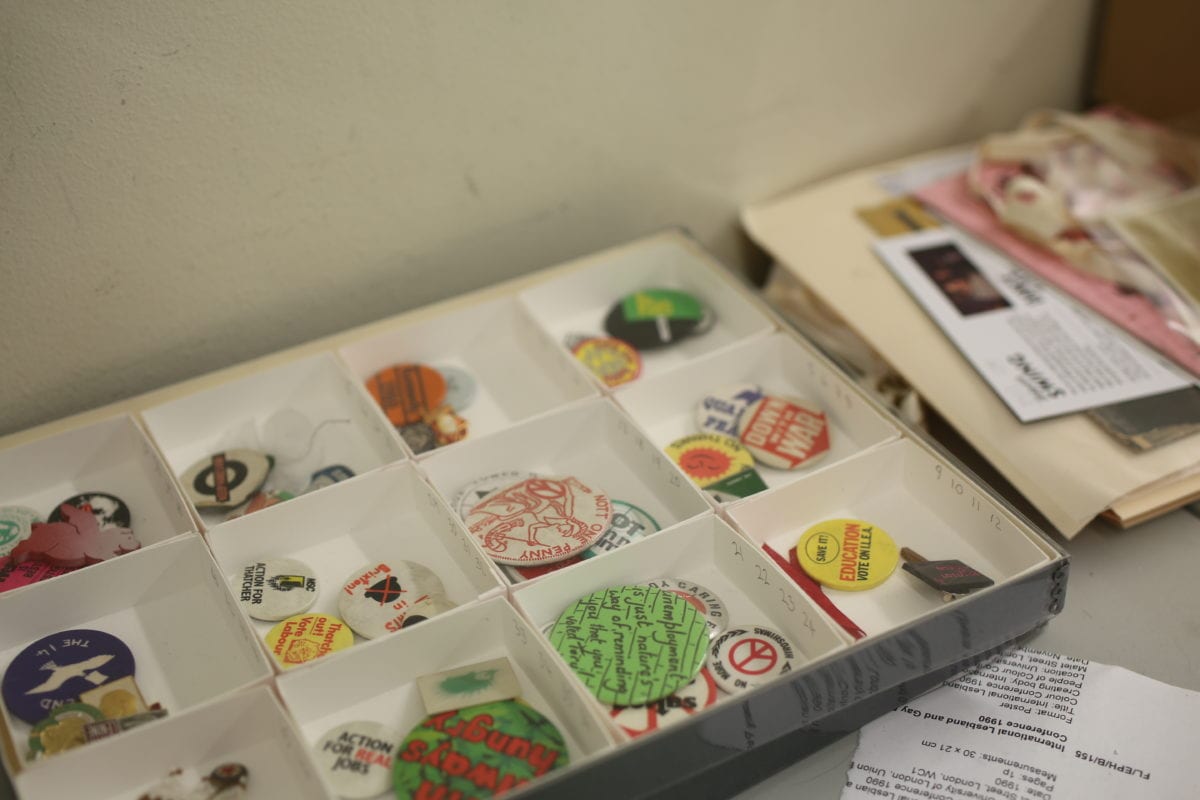

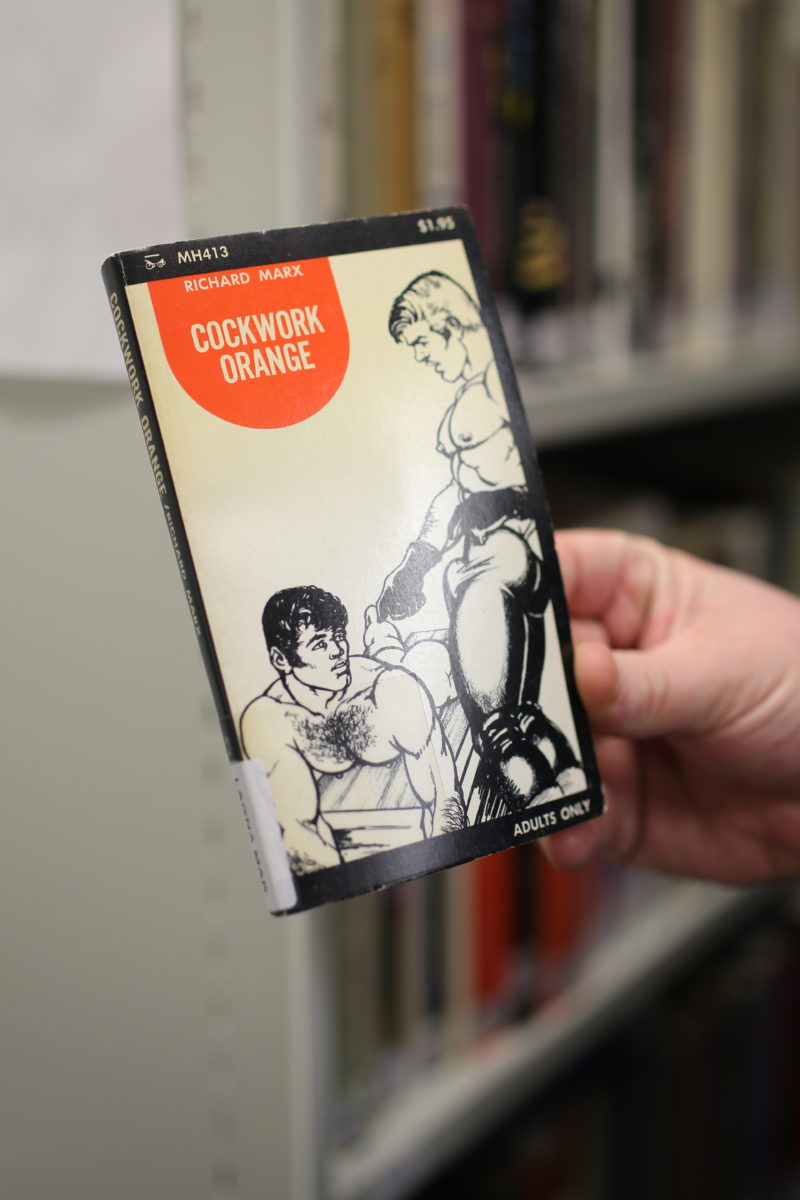

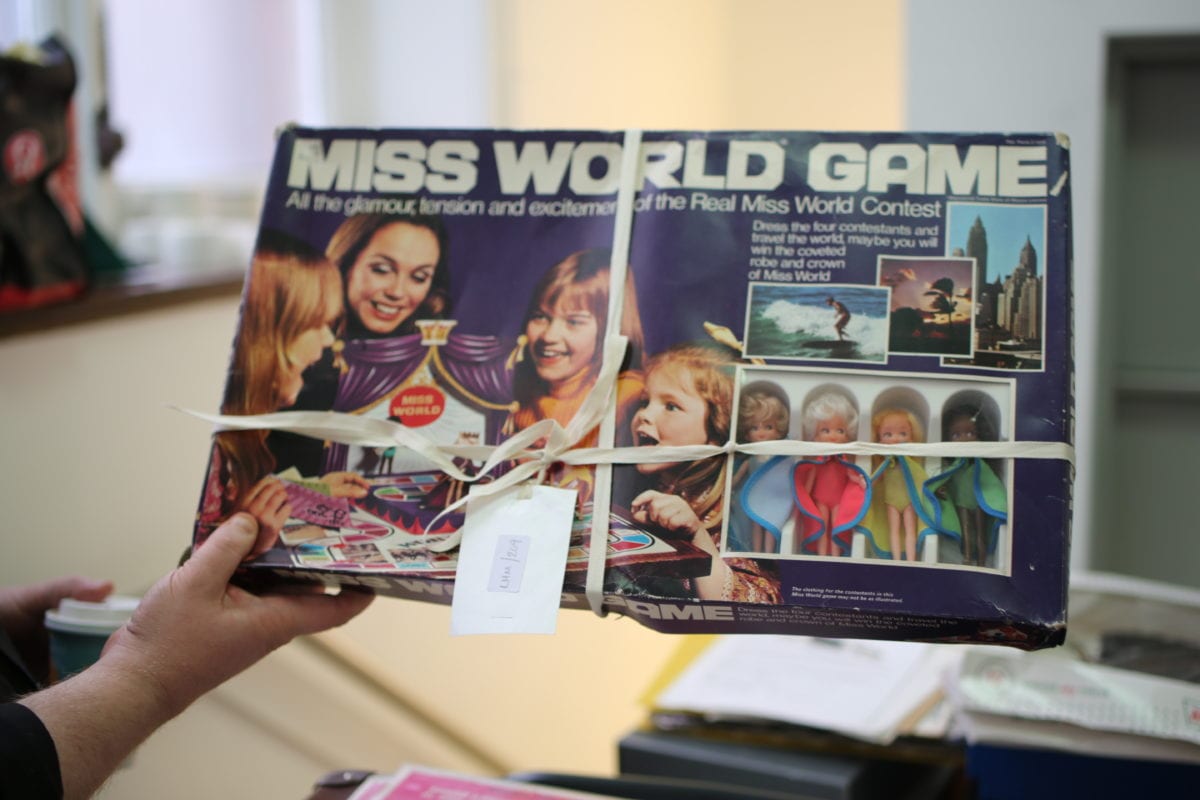

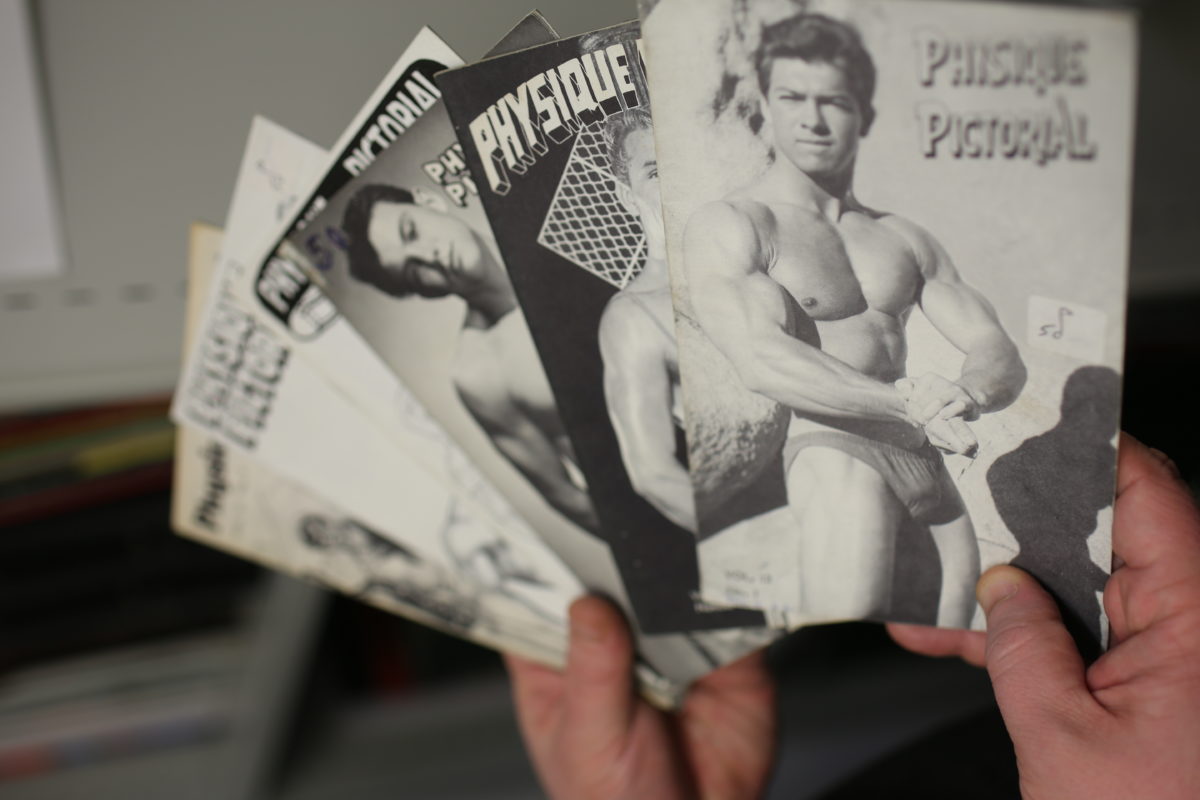

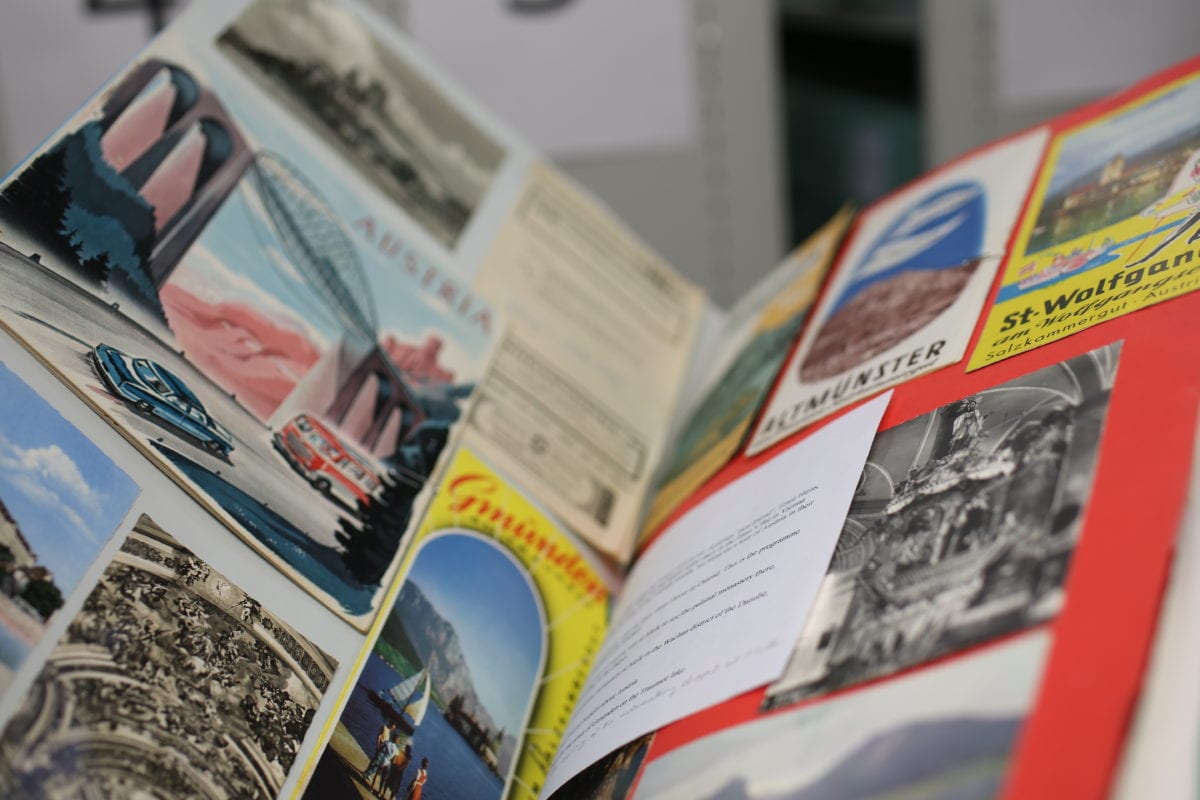

“One thing we’re particularly keen on here is everyone been important—not just the big figures and the big campaigners,” he says. “We’ll take anything from anyone, because history is more about us than it is about people we’ve all heard of.” What this means is that the archives house a gloriously strange and broad selection of ephemera, ranging from scrapbooks to magazines, badges to wizard outfits from queer protest and performance group Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, t-shirts, people’s personal diaries to a large silver cock(erel) donated by a rubber leather fetish club in East Anglia.

Said cock was one of the presents given among members of the group, who perhaps surpassingly, also kept incredibly intricate minutes of their meetings. “People think that because it’s leather it must all be filthy, but oh no,” says Dickers. “It’s more about the vol-au-vents, and which subcommittee will be looking after the entertainment.” Bishopsgate also houses the LGBT charity Stonewall’s collection; and that of Switchboard, the LGBT+ Helpline.

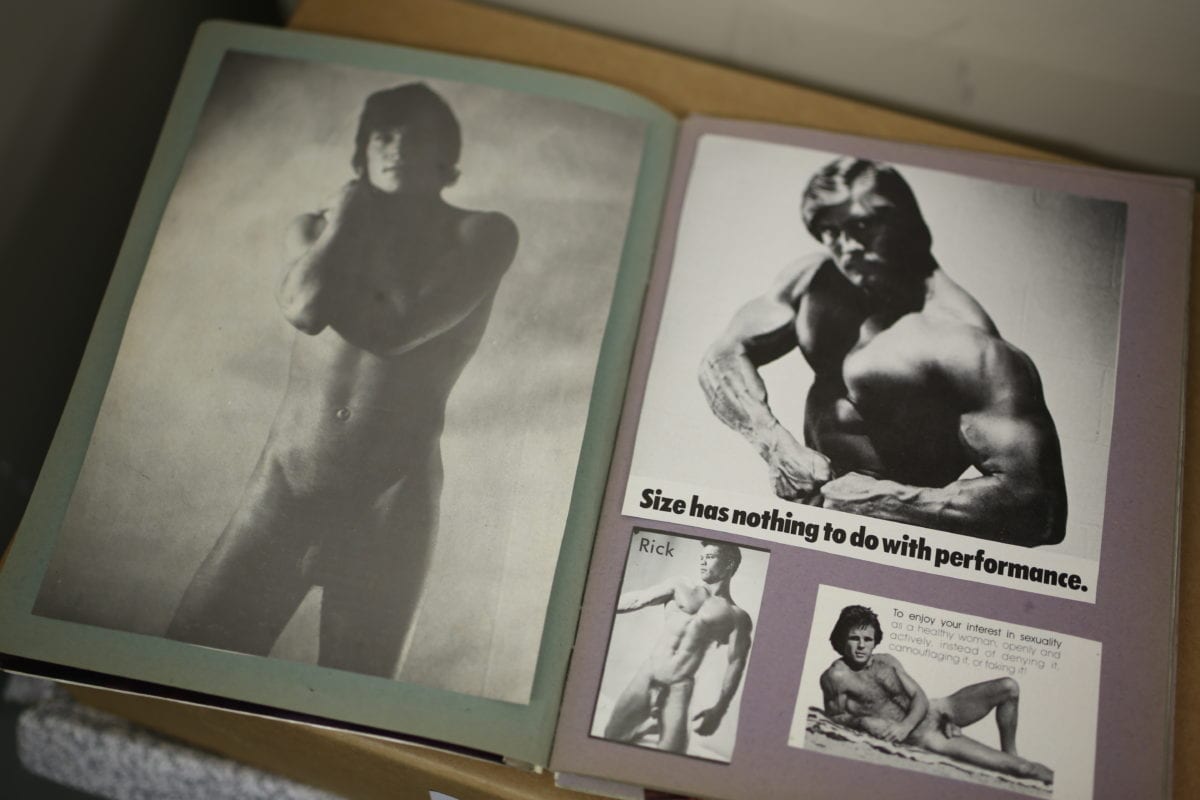

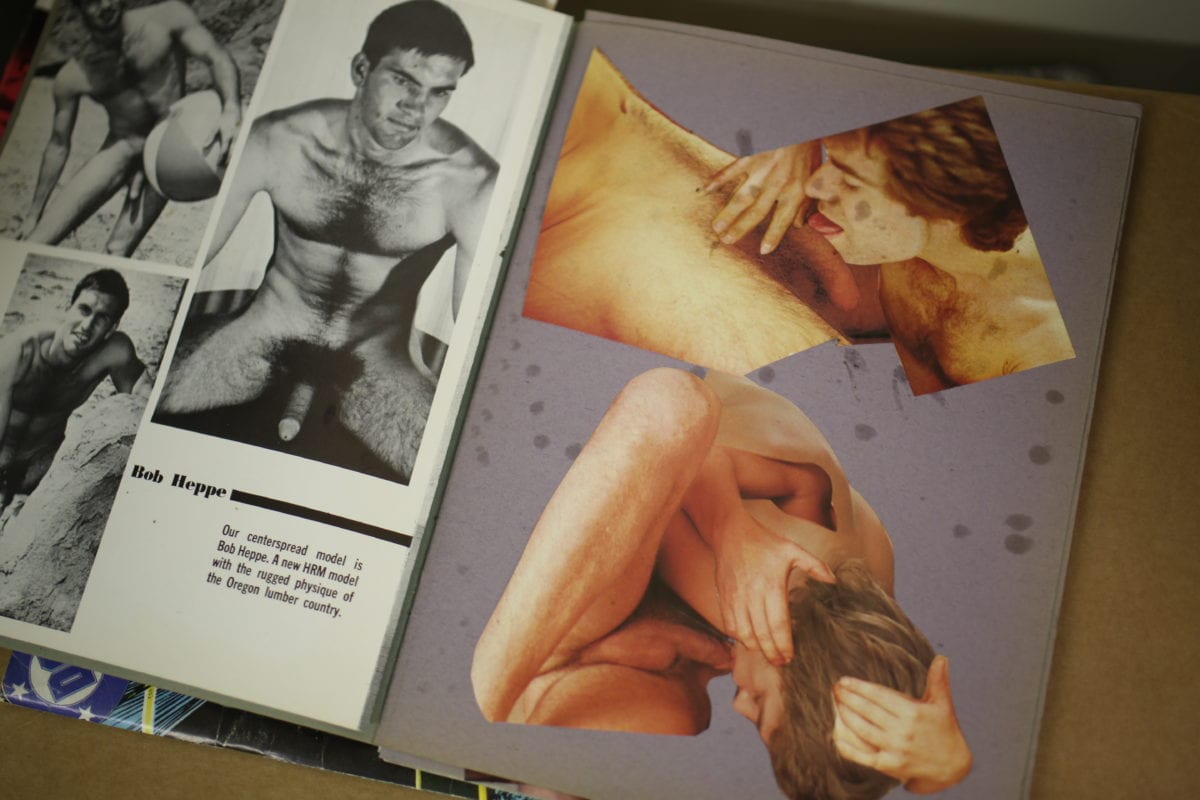

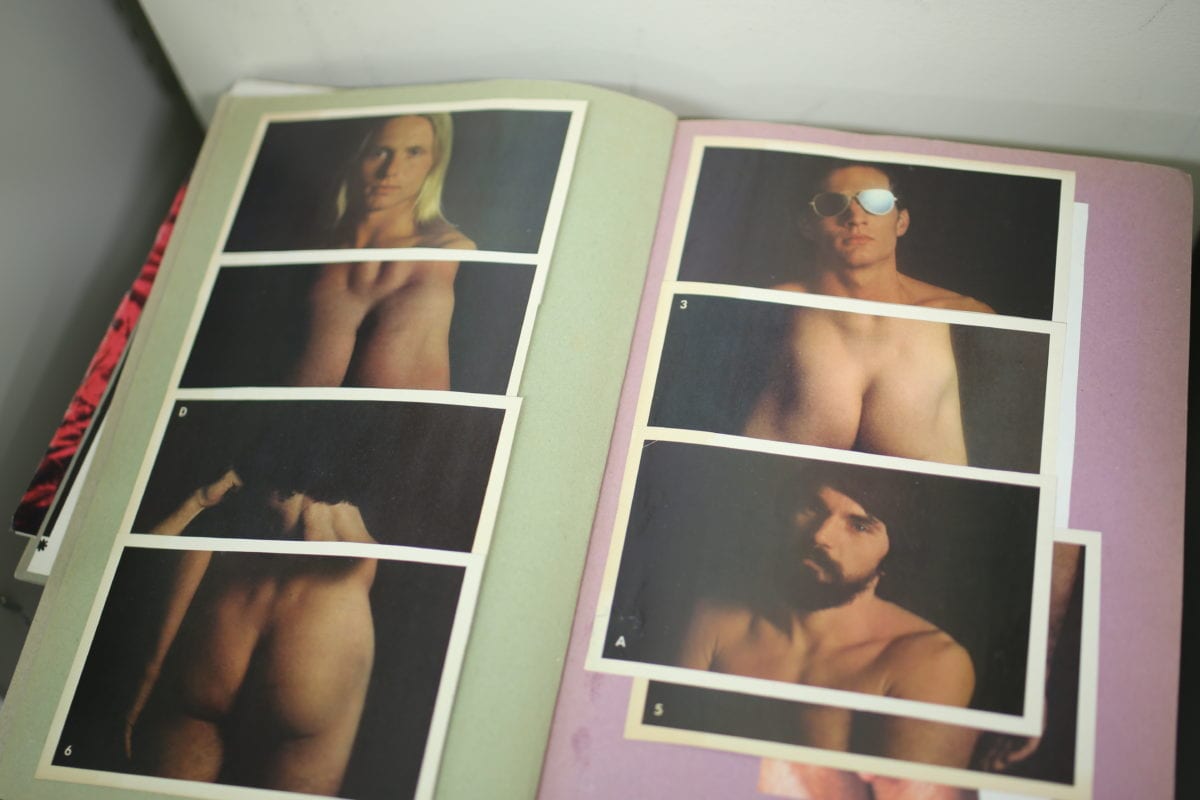

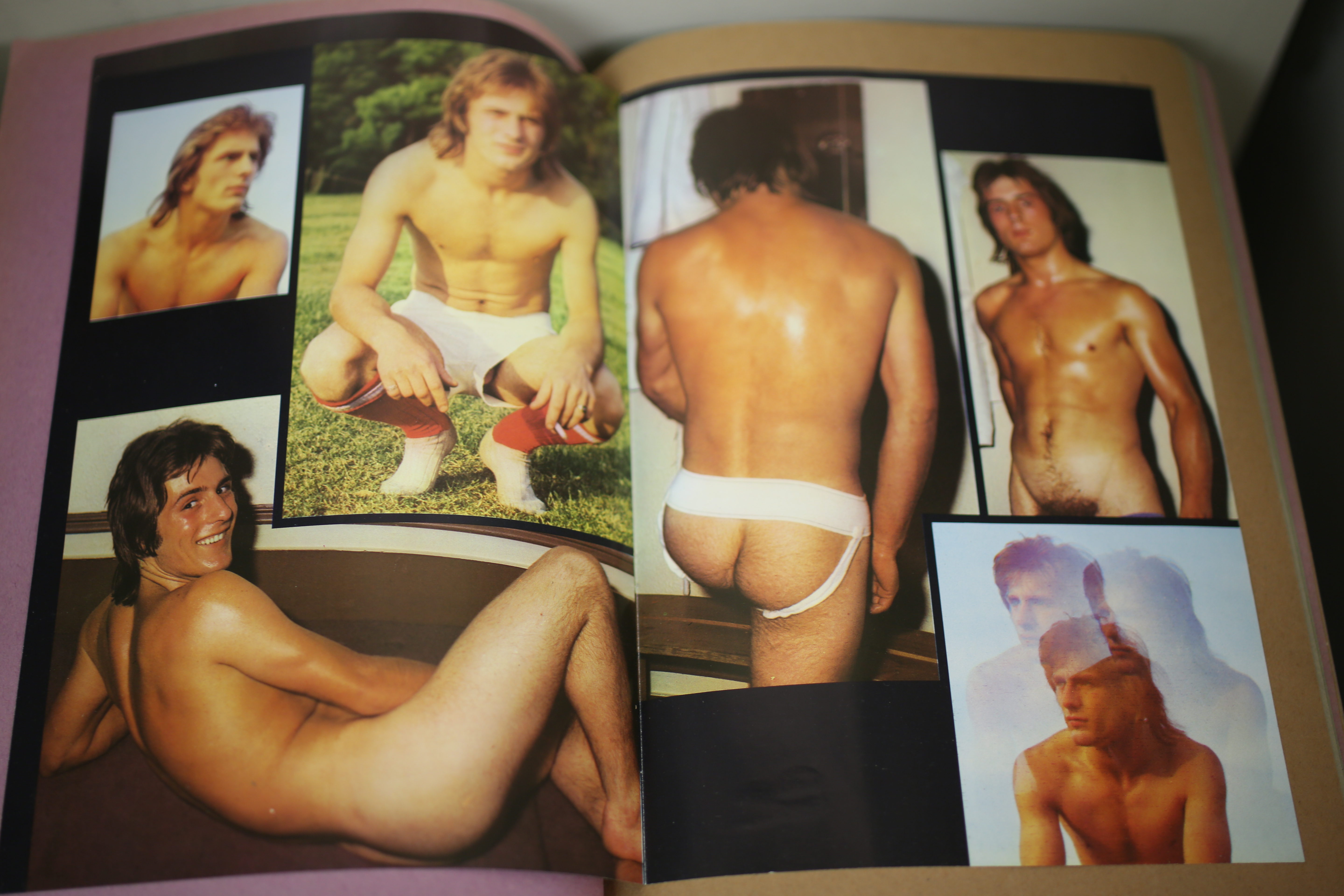

Among the most compelling items Dickers shows us is a series of scrapbooks, which arrived through a lawyer looking after the estate of a vicar who, during his lifetime, was said to have been vocally homophobic. The images in the book are mostly of soft(ish) male gay pornography; sometimes lovingly collaged together and hidden within twee, floral covers that appear oh-so innocent from the outside.

Another highlight is a collection of around 250 polaroid images—again, discovered after their creator died—showing the faces, torsos and penises of the photographer’s lovers. “Some of it is absolute filth!” says Dickers. “Good on him.”

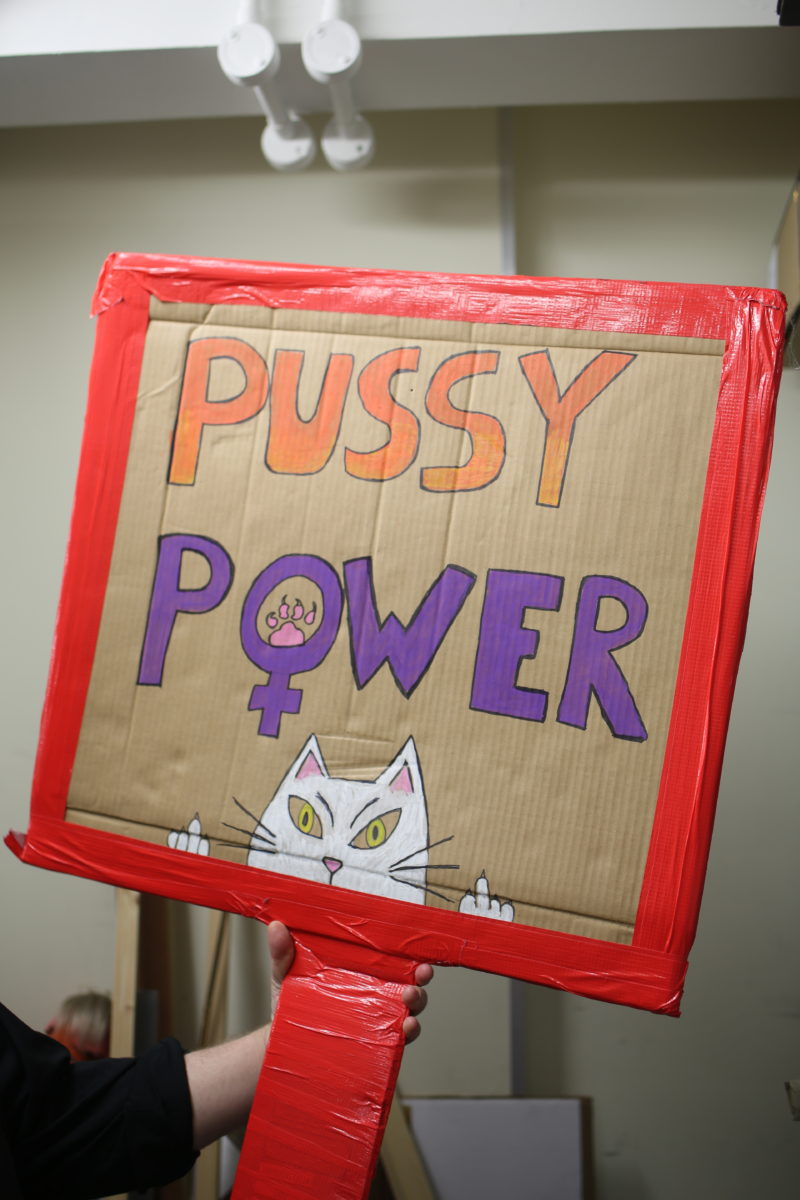

Away from such glorious filth, the archive also houses some adorable artefacts: badges and T shirts from the short-lived 1970s group Gay Vegetarians, for instance. There’s also a wealth of weird and wonderful items and placards from protest campaigns: a talking Trump in a cage (squeeze his finger, and out pour farting noises and ludicrous mutterings) sits next to Women’s March banners. “We’ve got one of the biggest collections of east London takeaway pizza menus,” says Dickers. “In twenty years, someone will will come in from Oxbridge going, ‘I’m doing my PhD on late twentieth century pizza delivery,’ and we’ll have all the gear.”

Is there anything, then, that the archive wouldn’t take? “If it fits into the collection areas we collect, we’ll take it,” says Dickers. “Who are we to say what history’s going to be important? I try to make sure it’s very broad, so we collect a lot of protest material, campaigning materials and so on, as well as a lot of LGBTQ+ material. But I also want to make sure everything we collect about queer history is not just about being pissed off and campaigning. And, not everything is about sex.”

“Who are we to say what history’s going to be important? I try to make sure it’s very broad”

The archive staff (four full-time and three part-time, helped by some volunteers) have come to be pretty unshockable in what they see coming in—“It’s just another cock, we’re so used to seeing willies,” as Dickers puts it. However, the archive doesn’t collect actively right-wing political items, and some of the most shocking pieces Dickers has seen are things including National Front election addresses outlining beliefs that black and white children shouldn’t be taught together. “I find that more offensive than any body parts, or anyone doing something to somebody else consensually,” he says.

Though the collection is described online, at the heart of Bishopsgate’s approach is their open invitation to visitors to come in and see the objects and printed materials for themselves. “That’s quite different to most archives, we don’t have a lot of forms and things to get in,” says Dickers. “A lot of archives tend not to want you to come in—things are hidden away for the future. But what future are they waiting for? We do as much as we can to get it out there and make it alive and let it inspire people. If you just put something in a box downstairs, you might as well burn it—it’s dead really.”

Dickers is clearly a man who loves his work—augmented by his curious (nosey, by his own admission) fascination with the lives of others—and this archive feels like not just a job, but a passion for him. Having studied for a history degree, he’s been with the Bishopsgate Institute for the past fourteen years. It was under him that the collection diverted from one more focused on family history and London history, “to be more of a radical, queer one,” he says. “I always say archiving is the most political job you can do. You’re deciding what’s kept and what isn’t. Even how you describe something in the catalogue dictates how someone’s going to be able to find it. Unfortunately with Trump, I can’t just say ‘horrible bastard in a wig.’”

“The whole job is about how you provide access to stuff: we are a very, very open archive that lets anyone in. We collect archives about communities and groups that maybe don’t feel that they’re represented in archives; like the trans community, the non binary community… You have to be open and welcoming.” He adds: “People know that if they donate stuff to us it’s going to be looked after and treasured, but also that it’s going to be alive and looked at and enjoyed.”

Words: Emily Gosling

Photographs: Louise Benson