The financial and academic resources needed for accessing art history texts are significant. University libraries are rarely open to the public for borrowing, and exhibition catalogues can often cost up to $100 when sold as standalone items. This leaves a gaping hole in arts education—putting significant limits on who can participate in, absorb and advance the discipline. When coupled with a long tradition of white canonicity and racialised academic gatekeeping, the picture appears increasingly bleak for Black and other ethnic minority communities wanting to access texts.

View this post on Instagram

Projects like Detroit’s Black Art Library seek to redress this imbalance via a simple process of knowledge accumulation and sharing. With a background in arts education, including fellowships at the Toledo Museum of Art and St. Louis Art Museum, founder Asmaa Walton began collecting Black art texts in late 2019 as a way of creating a resource for community education. “The lenses that we are used to consuming art history through have to be refocused,” she tells me.

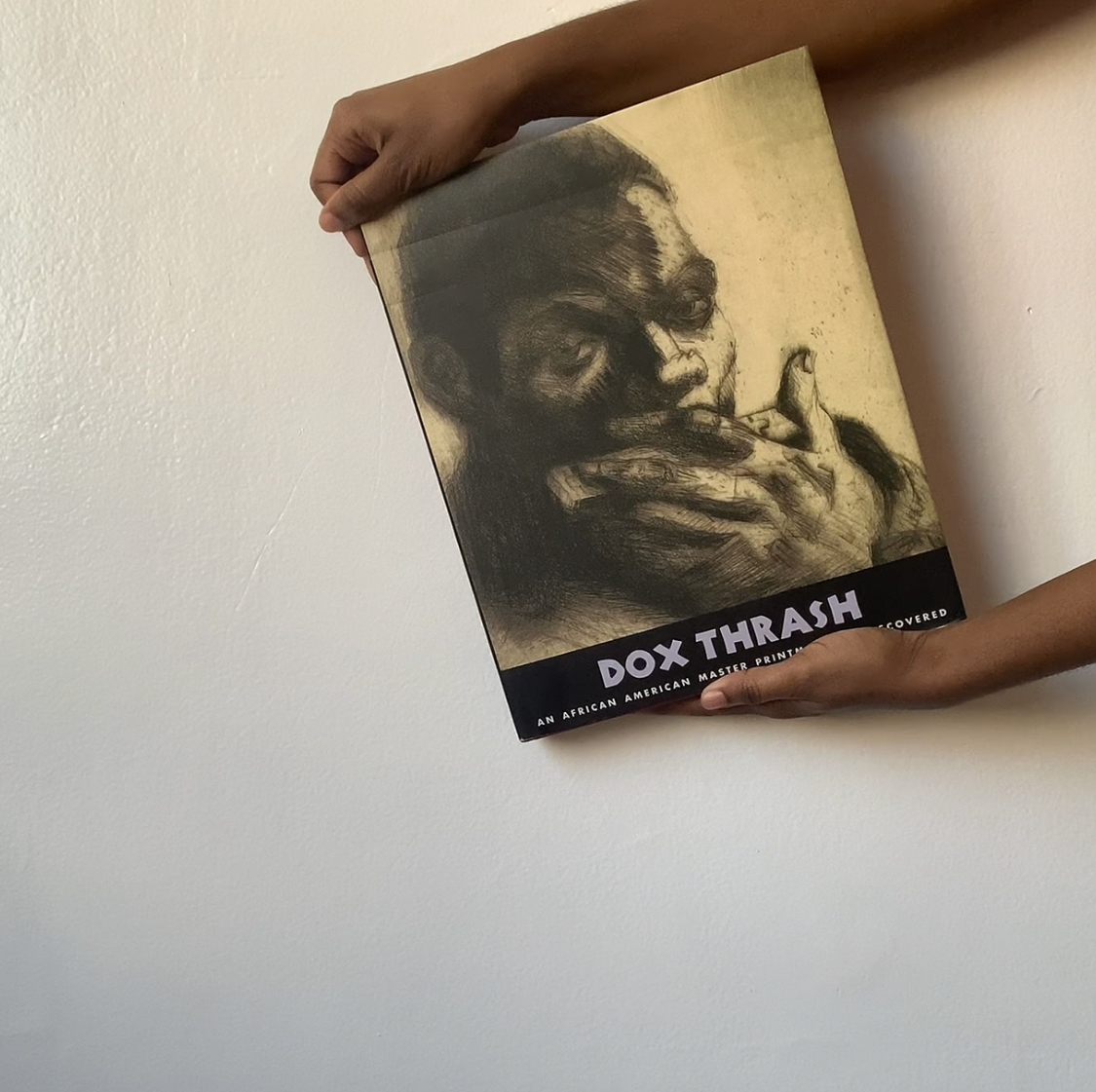

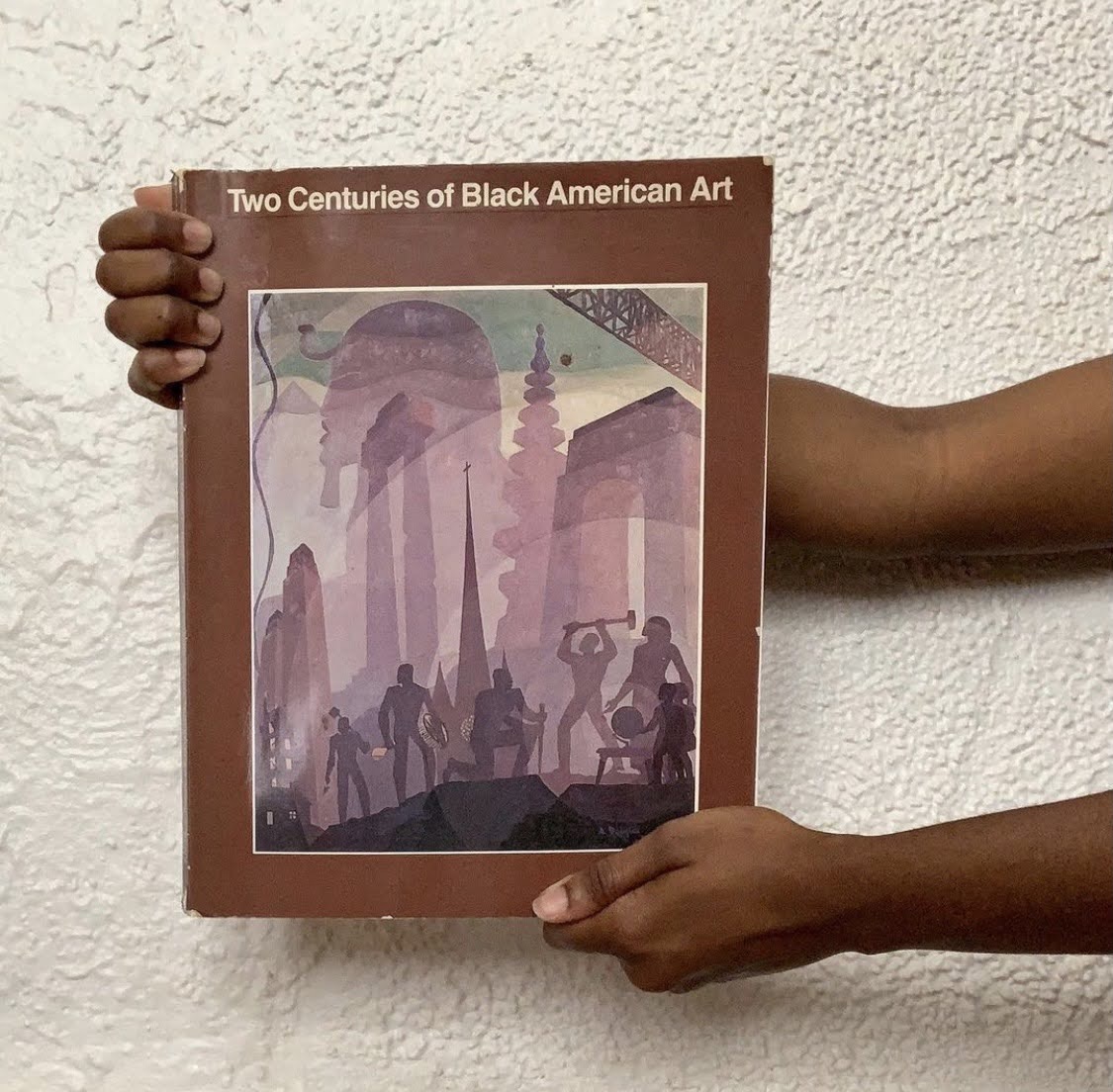

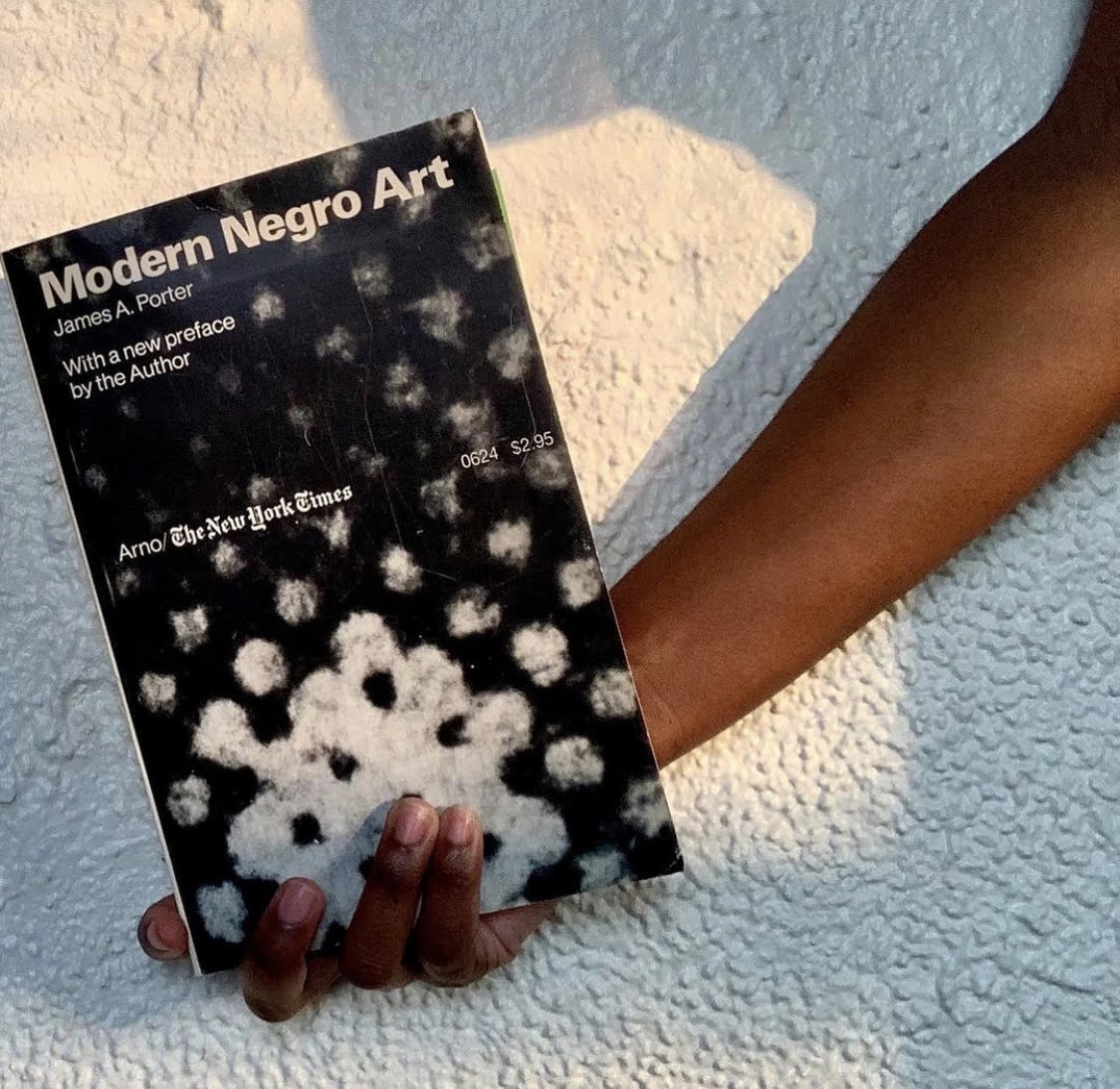

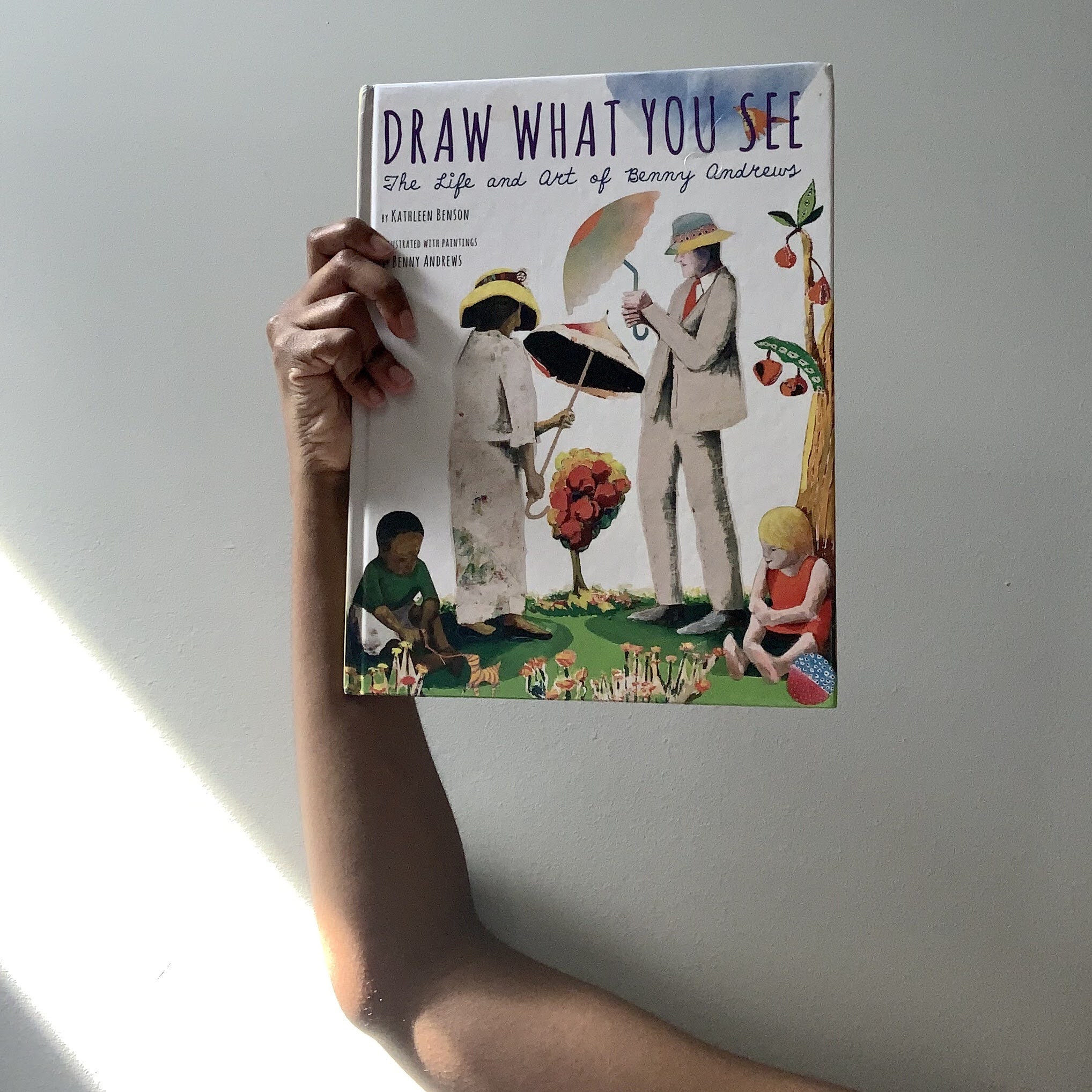

Now fundraising for its second year expansion, the library is a prominent feature of the Detroit Black arts scene, and is currently installed at Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. Texts range from seminal works like Modern Negro Art by James A. Porter to Faith Ringgold’s illustrated children’s stories—a diversity that encourages a collective history to be drawn across genres, rather than viewing groups of texts in isolation.

Walton’s role therefore sits somewhere between researcher, curator, educator and facilitator. In offering a list of texts that best capture the project’s essence, its range and scope become clear. Among them are inventory-style works like Ten Negro Artists From the United States: First World Festival of Negro Arts, Dakar, Senegal, 1966 by Hale Woodruff (1966); Explorations in the City of Light: African-American Artists in Paris, 1945–1965 by Audreen Buffalo (1996); and Six Black Masters of American Art by Harry Brinton Henderson and Romare Bearden (1972). These sit alongside single-artist monographs and thematic studies, including Mary Schmidt Cambell’s Tradition and Conflict: Images of a Turbulent Decade 1963-1973 (1985) and Charles Ethan Porter: African American Master of Still Life by Hildegard Cummings (2008). All are a potential gateway for readers of different levels of arts education.

“The lenses that we are used to consuming art history through have to be refocused”

This historicist approach also involves rediscovering the relevance of former standalone art exhibitions which, typically staged for brief runs of only a few weeks, dramatically increased the visibility of Black artists like Beauford Delaney, Horace Pippin and Augusta Savage, and are often housed in spaces with strong African-American ties such as the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York City. Following the exhibition’s public run, they are frequently consigned to archival or private collections. The accompanying exhibition catalogues are an important subset of the Black Arts Library, which will further grow this year with exhibitions like the New Museum’s Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, currently showing in New York City.

“I always tried to use my personal social media as a way to educate my peers on things I find cool about Black Art,” Walton explains. “This project was just a combination of all of the things I loved and all of my interests (art books, Black art, and arts education). I wasn’t sure where I could go with this project, but I just decided I would start and see where it would lead me.” It has led to a modest but influential following for the virtual library on Instagram (artists Jordan Casteel and Tony Cokes are fans), where Walton showcases new acquisitions with disarming, DIY-style photoshoots. Recent additions include Passages, the exhibition catalogue to a 2014 retrospective of printmaker Robert Blackburn at the University of Maryland’s David C. Driskell Center, and Chicago curator Grace Deveney’s monograph on the acclaimed abstract painter Christina Quarles.

View this post on Instagram

Walton names the AfriCOBRA collective, Emma Amos and Nick Cave as just a small portion of artists and authors whose works she hopes to add to the collection in the future. The library now includes over 400 books and 100 other items, including clothing and photographic slides of works by Black artists. “I just think we’re in a space that has to move away from these types of canons,” she says. “We have established that they erase and rewrite many histories within the arts. This project has a goal of finding as many of those lost histories as possible so I can share them with others.”