Nearly three decades have passed since Marc Quinn presented the first iteration of his sculpture series Self (1991-ongoing), for which he has been drawing ten pints of blood from his veins every five years to mould his updated self-portraits. The busts depend on electricity to survive and remain frozen; however, the works radiate life through changes traceable on Quinn’s face. In each version, his face transforms, yet his medium remains strictly stable. In fact, blood is of the most resourceful materials artists can attain, which has been proven by the prevalence of bodily fluids used in lieu of paint or clay throughout art history.

During his imprisonment for obscenity charges, Marquis de Sade looked no further than his own excrement and blood to write onto his cell’s walls. Viennese Actionist Otto Mühl urinated into his fellow artist Günter Brus’s mouth in their performance collaboration Piss Aktion (1969). Necessity was the urge for De Sade, while for the Viennese Actionists or Quinn, utilizing bodily fluids to create art echoed shocking statements on mortality, indulgence and vice. Quinn’s current project, Our Blood, exemplifies the transition from subliminal manifestations about the self towards sociopolitical urgencies in response to systematic threats towards human rights during tumultuous times.

Slated to unveil in 2021 in front of New York Public Library’s Stephen A Schwarzman Building, two minimalist cube sculptures will be filled with blood donated by 10,000 resettled refugees and volunteers, including global figures such as Bono, Naomi Campbell, Kate Moss and Anna Wintour. Maintained at below zero temperature similar to his busts, these sleek geometric forms will not reveal which cube contains blood from refugees or others, underlining the biological unity humans share regardless of differences outside. “Blood was charged with politics back then, but in a way different way through HIV and Aids,” explains Quinn about working with the medium in the nineties and the present. “Everyone was scared of others’ blood.”

Brooklyn-based artist Jordan Eagles’s investment in emphasizing the stigma around blood started twenty years ago and culminated into a series of blood and resin works, among which is Blood Mirror (2015 to present), a sculpture and multimedia collaborative project to protest US FDA’s discriminatory blood donation policy for “men who have sex with men”. The haunting sculpture includes blood collected from fifty-nine gay, bisexual and transgender men, some of which include advocates and users of preventive HIV medication PrEP. Eagles’s most recent work, Jesus, Christie’s (2018), pairs a sale catalogue of Da Vinci’s recently-auctioned Salvator Mundi painting laser-cut to contain twelve medical tubes filled with blood from HIV+ undetectable long-term survivors and activists.

Bridging art history and medicine, Eagles taps into the discrepancy between astronomical figures (such as the $450 million the subject painting fetched) paid to acquire art and the growing need for funding for medical causes, such as cancer or HIV/Aids research. In Pissed (2017), Canadian artist Cassils collected their urine for 200 days into a minimalist sculpture, starting with the day the Trump administration revoked a bill allowing transgender students to use the bathroom of their gender identity.

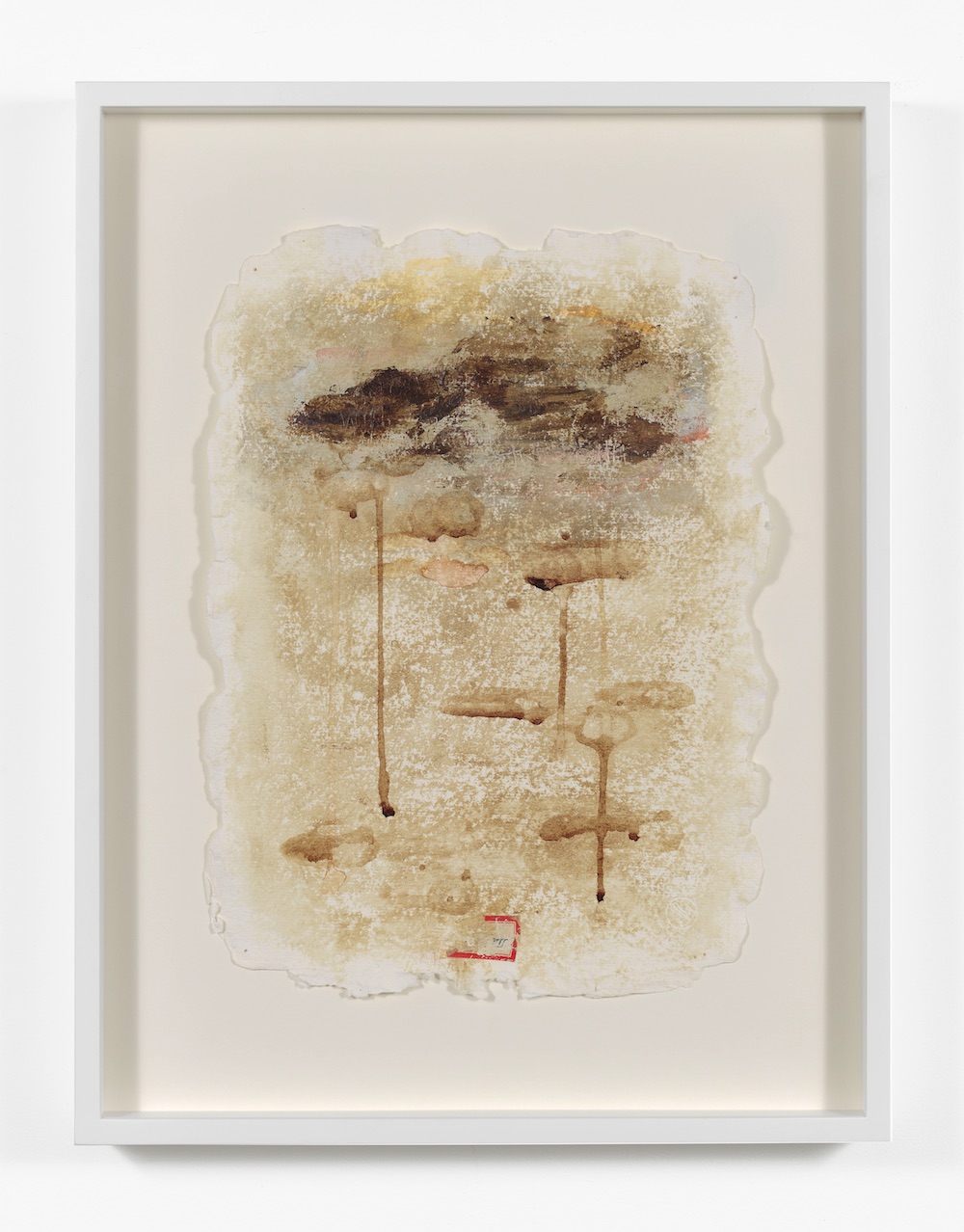

Painting with her own menstrual blood was initially a practical choice for American artist Harmony Hammond, who failed to receive the watercolours she had shipped from the US during her residency at the Rockefeller Bellagio Foundation in Italy in 1994. However, the medium gave her Blood Journals series the subtle yet piercing corporal undertone her oeuvre is known for. With her favourite Twinrocker paper at hand, the artist realized she already “had her own pigment” to paint, Hammond recalls over email. Her ongoing expansive survey, Material Witness, Five Decades of Art at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Connecticut exhibits the series, which radiates a bold redness that both alarms and soothes, manifesting a striking feminist statement with a dash of humour.

Similarly, Andy Warhol benefited from the chemical component of urine for his Oxidation paintings in later stages of his career when he attempted to veer away from his signature aesthetics and themes in the late seventies. A grand provocateur, he riffed on the almost strictly straight and macho history of abstraction with this series of urine-covered paintings, for which he invited visitors of his Factory to release onto canvases coated with copper paint and let chance decide the paths of wee stream on the surface. The acidic nature of urine and its reaction on the paint yielded unusual hues on the canvas, and the splashy effect of this painting technique captured a sensual fluidity.

Doubtlessly Warhol (who also created semen-stained abstracted Cumpaintings during the same era) intended with the Oxidation paintings to pay tribute to the kinky “golden showers” which were being performed at New York’s underground BDSM clubs at the time. Warhol’s experiments with urine coincided with a time when Robert Mapplethorpe was interested in the subject. The master of bringing gay subculture to the mainstream, Mapplethorpe captured Jim and Tom performing a “golden shower” for his infamous photograph Jim and Tom, Sausalito (1978), in which two men engage in the sexual act to manifest the dynamics of power and trust exchanged between them in the form of urine.

“One thing that has changed significantly from then and now is the age and status of the pissers,” notes art historian Jean-Claude Lebensztejn about the shift in the pisser image from early Christian art to the present in his 2017 book Pissing Figures 1280-2014. And, he adds, “The innocent, impish naked toddlers and the clothed adults who relieve themselves without ulterior motive have given way to images in which sexual connotations return to the surface.” Hence, Brooklyn artist Anthony Goicolea photographed his twenty-eight-year-old self as two boys on both ends of a peeing game inside a bathtub for his black and white photograph Pisser (1999) and noted on queer memory and dark side of childhood.

Two decades later, yet another Brooklyn artist Jes Fan furthered the kinship between urine and familial bond in their video Mother Is a Woman (2018), which documents the process of extracting oestrogen from their mother’s urine to produce a beauty cream. Their post-menopausal mother was reluctant to provide the content, Fan explains; however, they managed to secure two test containers’ worth of content and pursue a lab process called solid phase extraction, which is documented in the four-minute-long video, shot in a clinically hygienic setting with a commercial aesthetic, including a voiceover that declares, “Kin is where the mother is.”

Similarly, in her 2017 The Guggenheim exhibition, Life Is Cheap, New York artist Anicka Yi delved into connotations of sweat in terms of labour and identity, extracting sweat from Asian American women in collaboration with Columbia University and a Parisian perfumer in order to produce a scent that permeated the museum’s gallery. The conversation between femininity and bodily fluids found an unlikely medium—semen—when artist Faith Holland started collecting images of ejaculation from anonymous sources through an open call. The nearly sixty submissions that Holland received resulted in her digital painting Ookie Canvas I (2015), for which she applied semen drips into abstract forms and coloured them with striking hues. “Not just anyone makes a good pisser,” Lebensztejn declares in his book, concluding, “Head and cock have to be in agreement.”

Similarly, in her 2017 The Guggenheim exhibition, Life Is Cheap, New York artist Anicka Yi delved into connotations of sweat in terms of labour and identity, extracting sweat from Asian American women in collaboration with Columbia University and a Parisian perfumer in order to produce a scent that permeated the museum’s gallery. The conversation between femininity and bodily fluids found an unlikely medium—semen—when artist Faith Holland started collecting images of ejaculation from anonymous sources through an open call. The nearly sixty submissions that Holland received resulted in her digital painting Ookie Canvas I (2015), for which she applied semen drips into abstract forms and coloured them with striking hues. “Not just anyone makes a good pisser,” Lebensztejn declares in his book, concluding, “Head and cock have to be in agreement.”