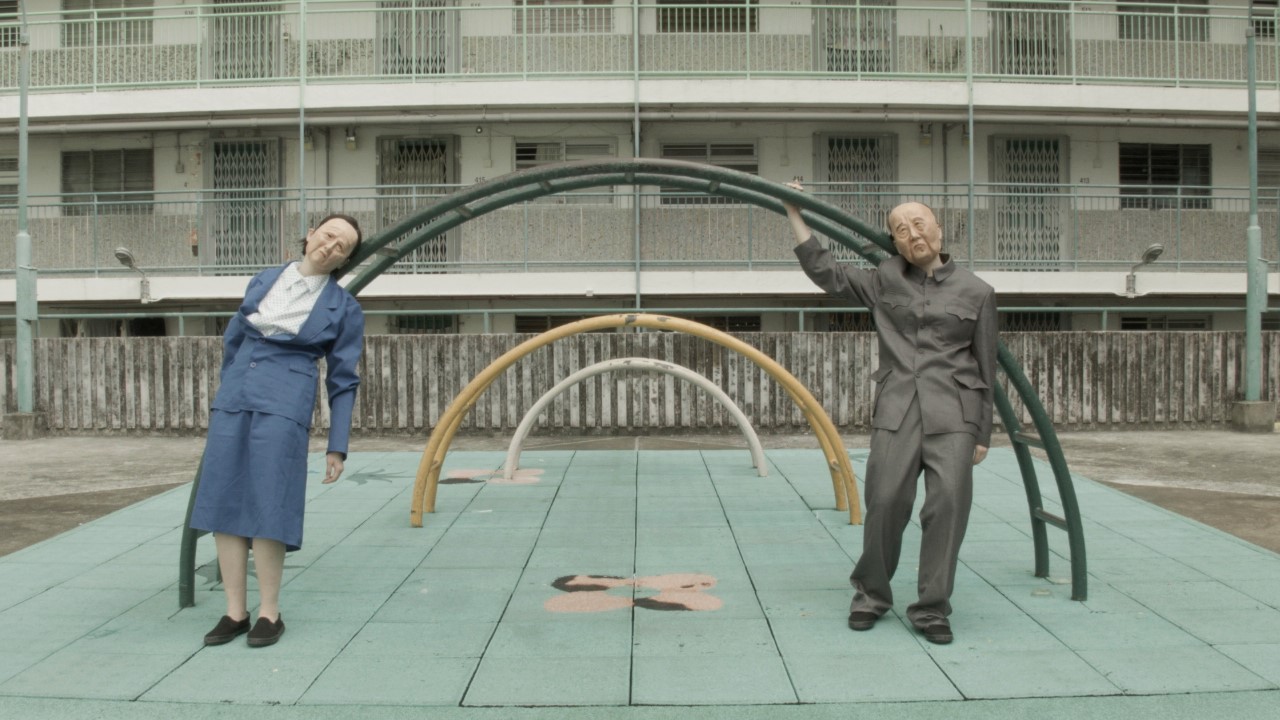

War of Perception 感知戰爭 (still), HD Video, 2020

A masked, white-robed and mirror-adorned spirit traverses the busy urban streets of Hong Kong in Bo Choy’s most recent film, War of Perception 感知戰爭(2020). The ethereal figure calmly draws attention away from the passing heavy traffic and brightly-lit commercial brand signs that vie for attention, while elsewhere protesters dance, a uniform mass in their plastic ponchos, balaclavas and goggles.

Bo’s video, performance and sound works navigate the experience of the present, through the poetics of memories, tales and reflections of the past, knitted together with speculations on the future. War of Perception was created during a very particular moment in Hong Kong, namely the unfolding events of the pro-democracy protests throughout 2019 and 2020. New extradition laws threatened to undermine the province’s independence and its citizens freedom of speech, yet these looming anxieties diffuse into the urban landscape of Bo’s imagery, guided by an enduring, ever-present spirit of the city. The collective spirit prevails under the oppressive threat of China’s paternalism: formed of the people who comprise it, both past and present.

I speak to Bo in mid-February on the day that the city’s lockdown starts to ease. “Life is starting again!” she laughs as gyms, cinemas and museums begin to open up. “I mean it wasn’t so bad before, you would just end up loitering around like teenagers in the parks and on street corners.” Back in the UK, in the midst of our third lockdown, I jokingly envy Hong Kong citizens even their ‘loitering’ freedoms’, but as Bo points out, “the population density here is so high and people live in such tiny flats, it would be really inhumane if you couldn’t leave your home.” We talk about how it is hard to find open space in Hong Kong, beyond the small squares with the odd bench and shrub, where the old folk sit and chat. “There’s a real ideology here that open space needs developing, space is to be made profitable.”

Bo has made London her home for the past 17 years, since her late teens, and each time she returns to Hong Kong she feels its palpable transformations. The flâneur spirit of War of Perception showcases a reassuring continuity, stepping into an elongated temporal reality of the city: elders roam their childhood hangouts, ghosts linger and memories resurface. Meanwhile, over dinner at home with Bo’s mother, news broadcasts flash past on television screen, fleeting instants in the long unfolding life of the city. She describes the film as “a quest to search for the truth, in a society where lies and rumours abound”, yet it avoids didacticism or any conclusive narrative. Instead, Bo’s liquidity of storytelling and imagery captures possibility, invigorated energy and an enlivened aura, rejecting any static description.

“It’s a quest to search for the truth, in a society where lies and rumours abound”

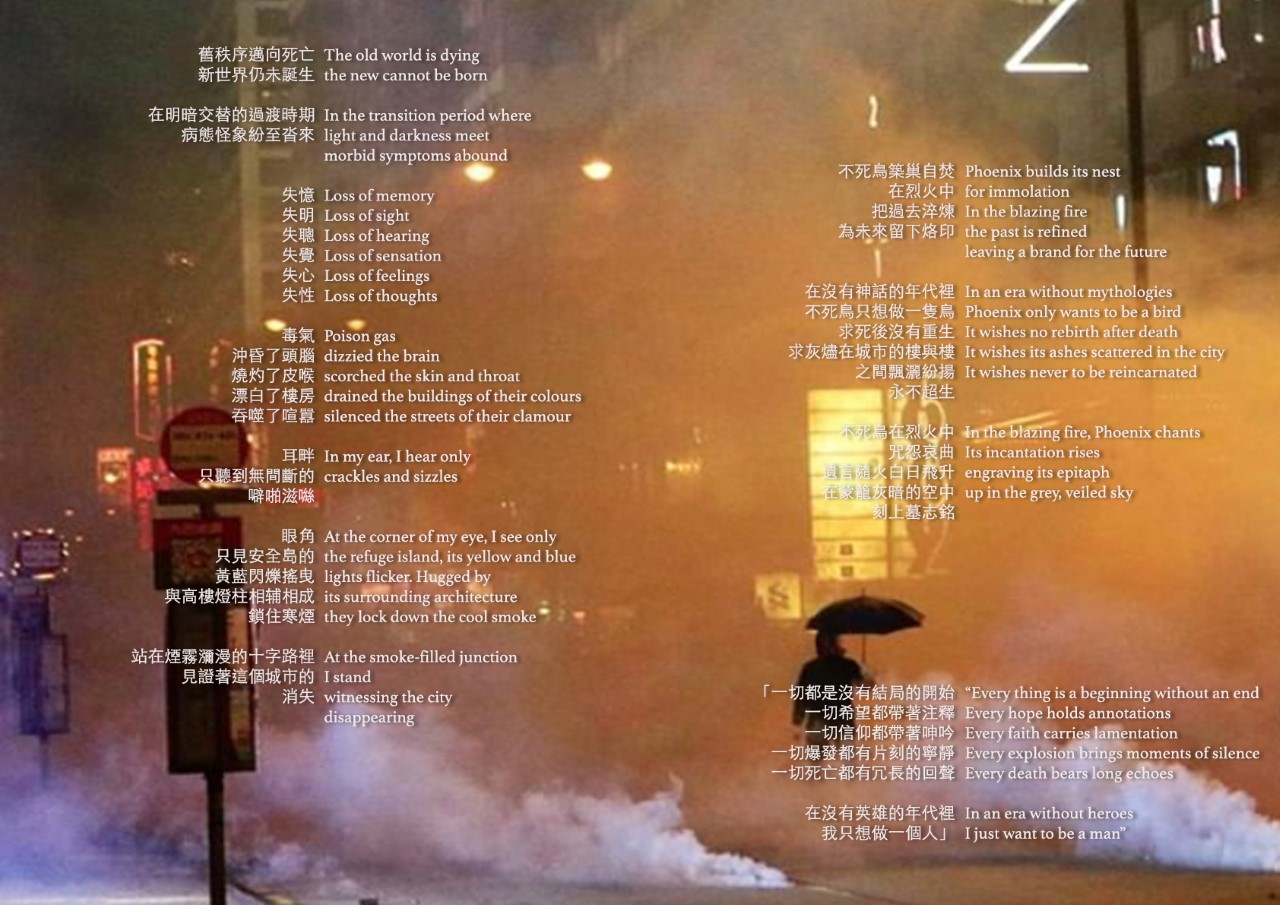

Against the backdrop of both climate change and the pandemic, with our species and ecosystems seeming ever more precarious, many anxiously sense the ground slipping away beneath their feet. In Hong Kong this anxiety is overlaid with the precariousness of the city’s political and social autonomy. Bo moved back to Hong Kong last year to sit out the pandemic: when I ask her how she seeks ways to feel more grounded within a city undergoing constant transformation, she admits it has been on her mind a lot since being back. This instability has emerged in her work through speculation on how the environment affects the city’s inhabitants, both those alive today and spirits from the past: “everything remains in the ether”. In her performance Gau Wu Oi Ming 鳩嗚哀鳴 (2020), the image of a lone citizen, bearing a protective umbrella and standing amid a smoke-filled street, is projected on the gallery wall. Bounced out of the projected frame, reflected around the gallery walls by her mirrored robe, the imagery is refracted amongst the audience.

Bo herself translates the work’s Cantonese title Gau Wu Oi Ming as meaning: “crying randomly and sadly”. It’s also a homophonic play on the Mandarin phrase for shopping, “gau wu”, which has become a metaphor for protest. In 2014 a pro-government, anti-democracy campaigner told a reporter that she was protesting for “gau wu”. Later, when Hong Kong politician CY Leung urged shoppers to return to the busy commercial district of Mong Kok after the clearance of the pro-democracy Occupy movement, those same protestors mockingly returned to their outposts under the pretence of ‘shopping’, adopting ‘gau wu’ as a satirical term for protest. Bo’s play on the subversive slogan evokes a cycle of resurfacing and resituating of emotions and social ties among the citizens of Hong Kong. “The old world is dying/the new cannot be born,” the film’s voiceover intones. Channelled through the spirit, Bo narrates the poetics of a phoenix’s aspiration to have its ashes spread through the city, but its rebirth is inevitable: “every death bears long echoes.”

During our meandering conversation over Zoom, Bo wonders, “Are people more anxious in Hong Kong because they don’t have a connection to the ground?” From her window on the 56th floor, the sprawling geometry of the city seems like a labyrinthine urban simulation, detached from the lives that play out within it. Living in such a ruthlessly capitalised urban environment, Bo says, dampens your sensitivity to circadian rhythms, changes in the atmosphere and astrological movements. “Shamans call them ‘spirits’, but whatever name you give these forces, they are very real energies and vibrational forces which affect our lives,” she says. “It’s not so much about ethereal, otherworldly spirits, but tapping into our natural place and surroundings… We all live in high-rises: maybe in Hong Kong instead of being grounded in relationship to the soil, we are grounded in relationship to the sky.” While many of her contemporaries in London grapple with the anxiety of global transformations, framed within the politics of earthly and ecological narratives, Bo instead holds on to the intangible, airy ether that binds the city’s inhabitants together.

“Are people more anxious in Hong Kong because they don’t have a connection to the ground?”

Non-duality, or the notion of the ‘self’ as part of a larger fabric of a shared collective conscious, infuses Bo’s work. “I was obsessed with Carl Jung for a while, and now read a lot of spiritual and eastern philosophy. Both share the idea that we are all connected, where we are only aware of a tiny proportion of consciousness, our ‘ego’.” Unpacking a parcel in her East London flat in her 2016 film, un/folding in, memories of past generations are summoned through a box of seemingly disparate objects sent to her by her mother, that have come together through the coincidences of “a cunning game of recurring time and history.” The film ponders the resurfacing of memory and traces of the past in the contemporary, where former lives influence the present and direct future iterations of the self. As she holds a small doll with a red dress, narratives from the London Blitz and the Battle of Cable Street surface as personal recollections. “Memories imprint themselves on objects and places …The memory of somebody from the past is passed on and imprints itself onto you or energises you in a different way.”

Having been interested in past life entanglements in un/folding in and earlier pieces, her recent work traces these disembodied interactions between eras out into the collective urban space of Hong Kong. “When you die, your body rests with the material world but your soul, which is a form of energy, is released and reborn, taking its emotions with it into the new life,” she explains. “Everyone leaves an imprint in the atmosphere and sometimes you pick up somebody else’s imprint and absorb something new.”

In War of Perception

and the two performances, Phoenix Desires 慾火鳳 (2020) and Gau Wu Oi Ming, imagery and sounds reappear, her mirror-adorned spirit acting as a reassuring guide. Here infinitely more ‘nodes’ become entangled: people, stories and memories held among the collective urban ether. “Maybe being in such a densely populated place, the energy compacts and impact on how we live our lives,” Bo suggests. Like atoms vibrating in increasing heat, the elements of her performances energetically pulsate against one another: people, sentiments, actions and ideas. Overlaid, juxtaposed and compressed together, with both sensitivity and passion, Bo’s imagery, poetry and sound simultaneously provide emotional warmth as well as eruptive potential.

The Korean poet Myung Mi Kim once defined poetics as “that activity of tending the speculative”. This definition has been on Bo’s mind for some time: “Maybe in my work I act as a conduit between different worlds, linking the audience to them through sounds and images.” Kim’s words act as notations, marking out the spaces in between for the unsaid or unknown, the invisible or intangible. Likewise Bo’s compositions of imagery, sounds and stories offer pointers for that which is just beyond our conscious grasp. Her non-linear narratives are left incomplete: in forfeiting full authorship, the works have autonomy and agency of their own, allowing space for the viewer’s subconscious to permeate their fragmentary components.

“When people say that they see a ghost, maybe it’s just someone crossing through a different dimension…”

Bo’s outlook holds an affinity with a sense of circular time more often found within indigenous cultures, where past, present and future are seen to coexist simultaneously in a place or land. Throughout her work, tradition, memory and heritage resurface within the present, giving texture and form to the personal and collective psyche. In modern science, Einstein’s theory of special relativity dictates that ‘now’ doesn’t exist; only ‘here and now’ can be true. Bo’s films and performances teeter among varying temporal realities. “Everything is present, but in different dimensions that maybe we can’t access. When people say that they see a ghost, maybe it’s just someone crossing through a different dimension; someone who’s passed that space only a few weeks ago, but their memory is still there. Maybe it’s just our antennae or our senses that are slightly misbehaving in that moment to tap into this other dimension.”

Rather than attempt to untangle them, her works embrace the disorder that exists between self, family, society, nature, spirit, history, heritage and the urban landscape. There is a productive beauty in the “messiness of the city and the interrelatedness of beings within it,” Bo argues, and she offers a multitude of possible narratives to speculate on contemporary events. As she continues to find ways to tap into the bubbling constellations of the collective unconscious, her works conjoin past, present and future in a “moment ripe with revolutionary possibilities”. She presents a constellation of memory, awareness and hope.

Sophie Williamson is Programme Curator, Exhibitions, at Camden Arts Centre, London. She is the author of Translation (Documents of Contemporary Art), published by MIT Press in 2020