I can attest that I road-tested The Bigger Picture: Women Who Changed the Art World, Tate Publishing’s latest offering for ages seven plus. Admittedly, my little reader is only one. She was not exactly the right guinea pig—her interactions with the book were more tactile, rifling the pages and kissing a drawing of Patti Smith on page forty-one. Smith appears in a spread called Women in the Picture: six famous female muses from Renaissance beauty Lisa Gherardini (aka the Mona Lisa) to Lily Cole—who seemed to me to be a strange choice, until I read that she does in fact appear in six portraits in the National Portrait Gallery.

The colourful book was written by Sophia Bennett and illustrated by Manjit Thapp—the artist who also worked on Penguin’s The Little Book of Feminist Saints and Scribble Yourself Feminist. I can’t conclude from my one-year-old’s reaction whether kids will enjoy this book or not; it is a detailed and comprehensive history—if a little dry (a round-up of famous art schools in Europe seemed a bit of a filler, and I’m not sure how many seven-plus-year-olds, or how many parents, will want to read about them).

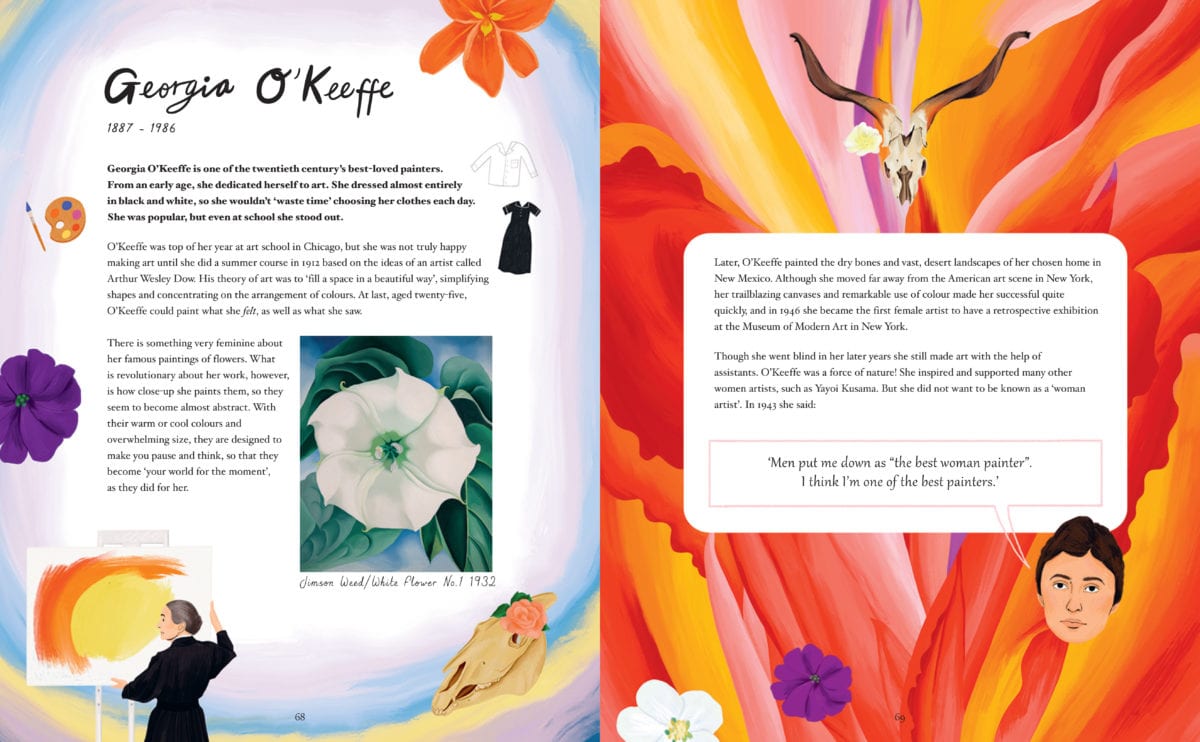

What the book does very well, however, is to include a diverse range of artists, and not only the usual Western suspects; it was especially exciting to see the Indian photo artist Dayanita Singh mentioned, as well as Simryn Gill and Fahrelnissa Zeid. Although the stories of the lives and work of artists take centre-stage here, other art world women get a mention, from gallerists, museum directors and even some of the critics. In this way, the book shapes a holistic understanding of the art world and how it functions, rather than fuelling any illusions about how artists become famous.

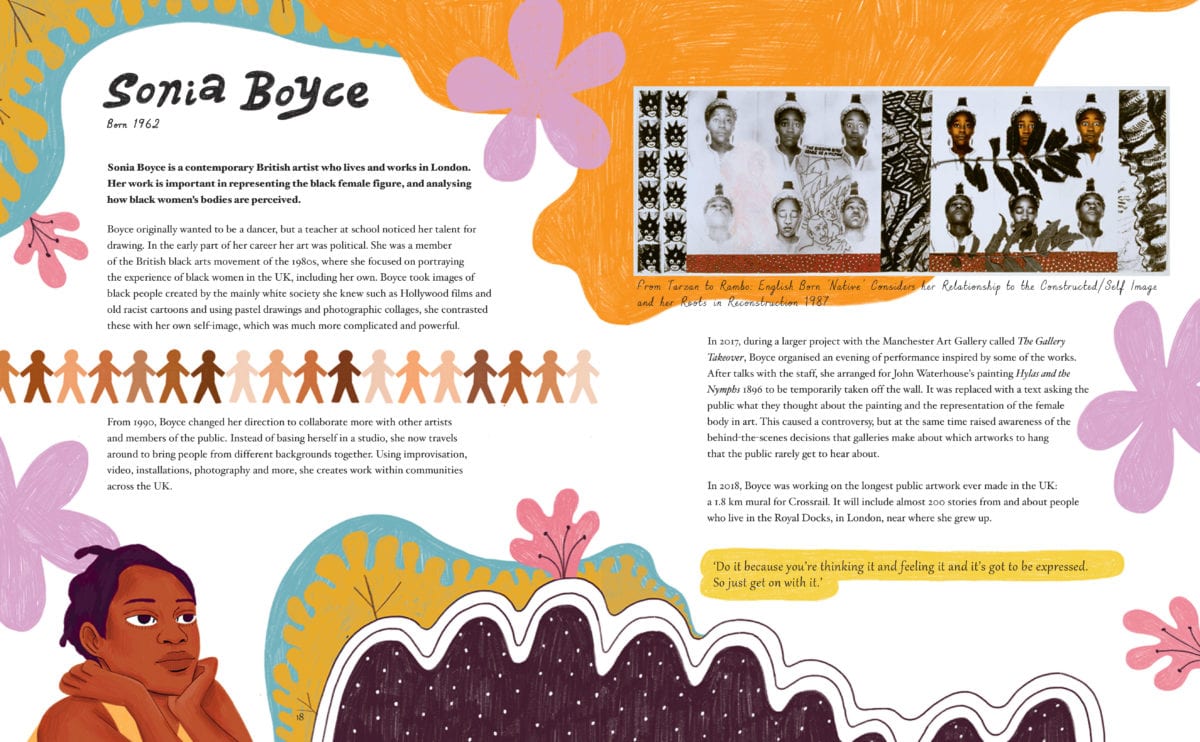

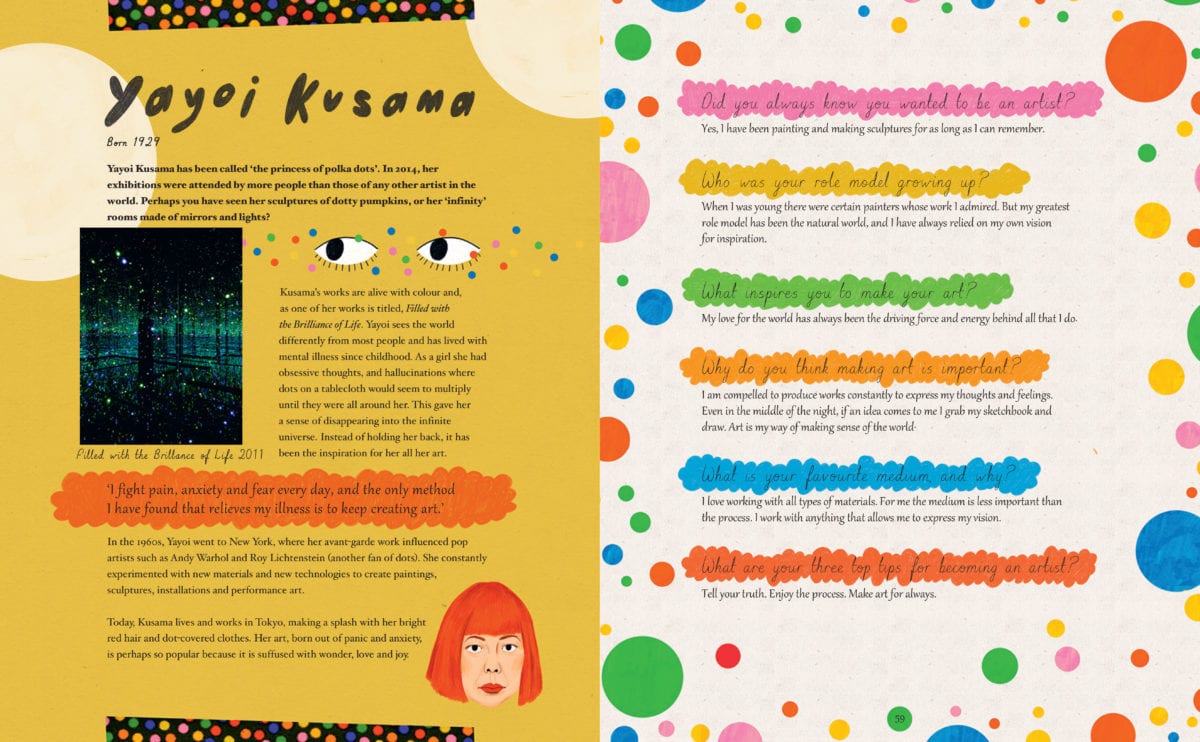

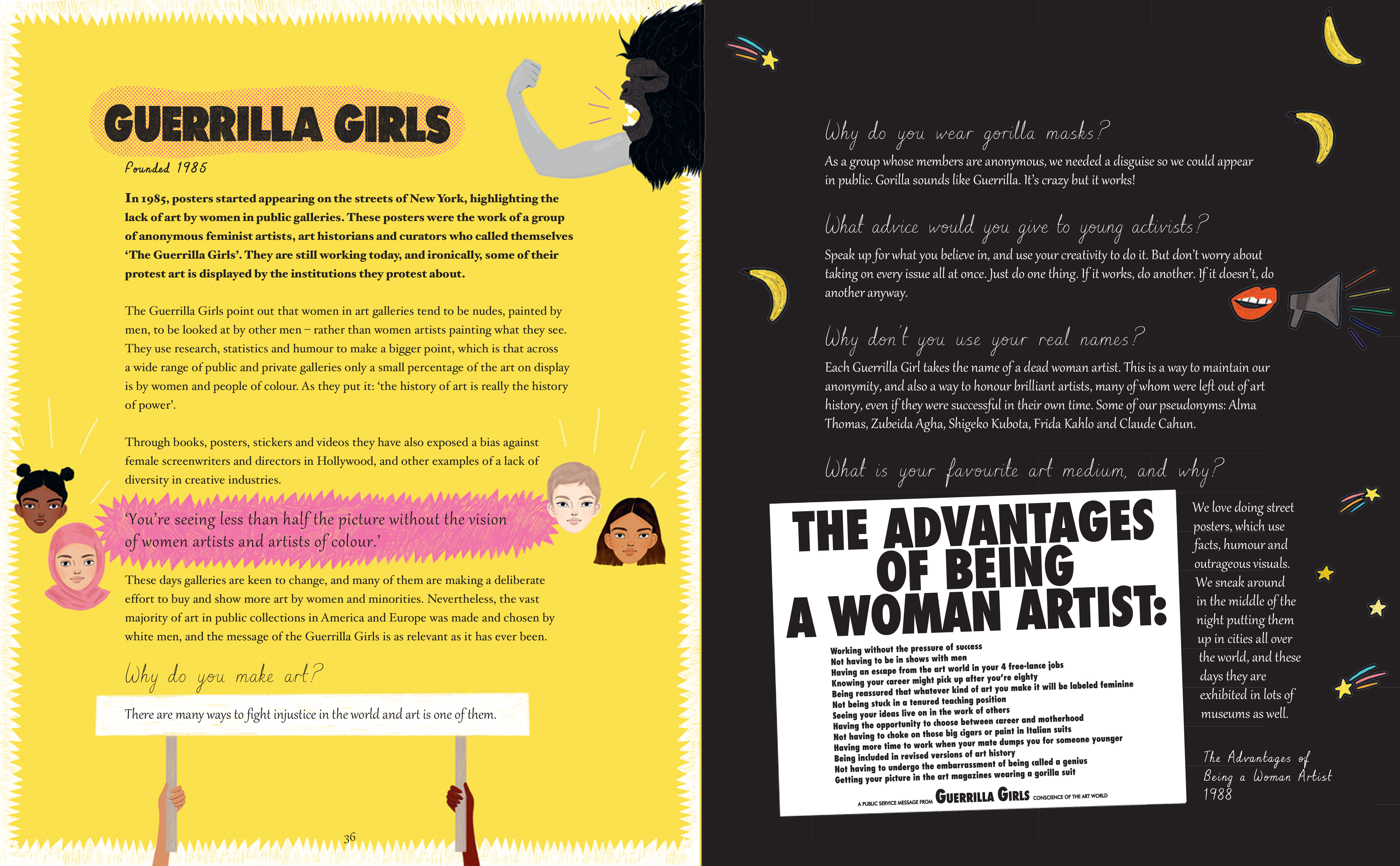

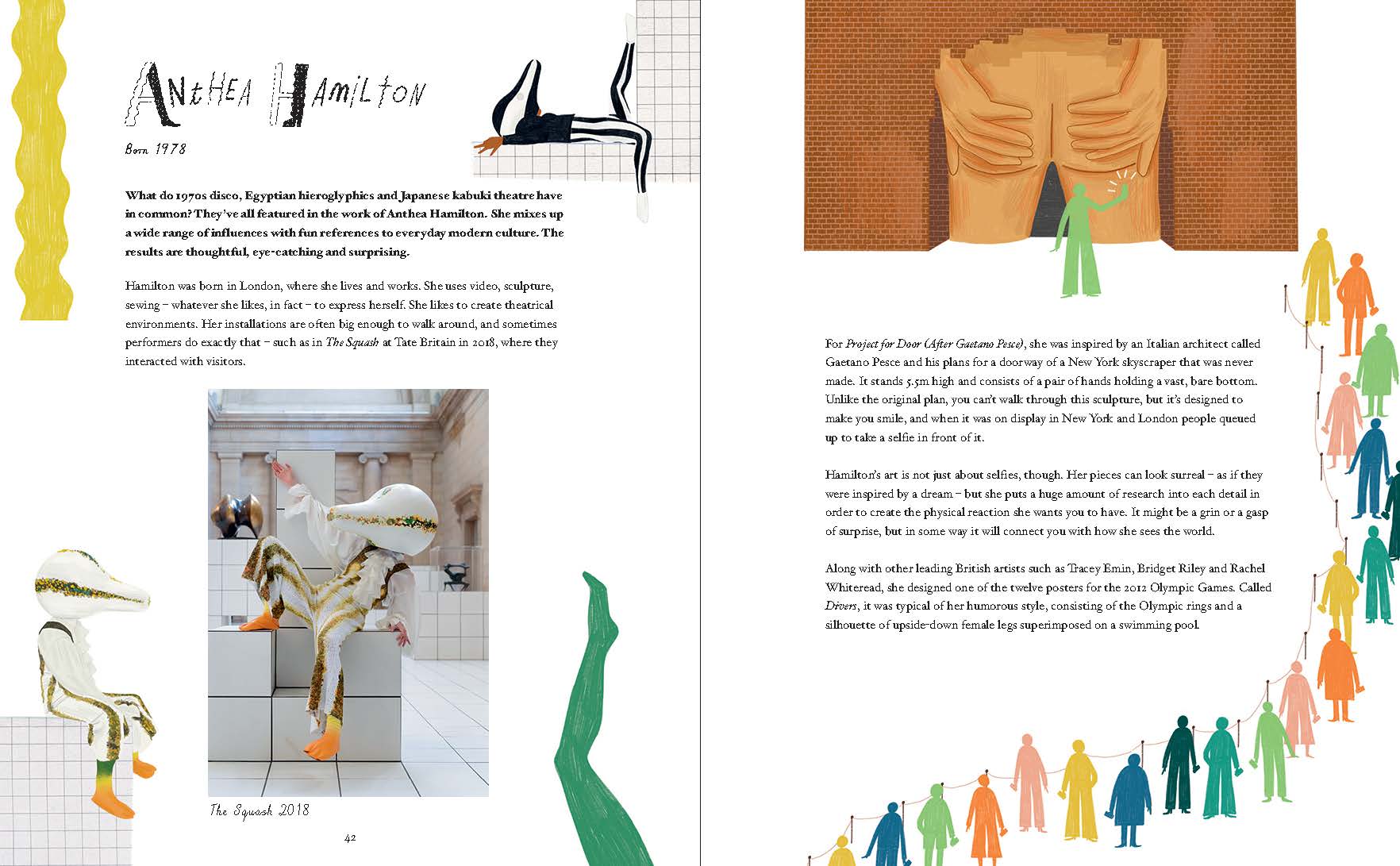

Another lovely aspect of this book is the original interviews with sixteen of the thirty artists, among them Lorna Simpson, Lubaina Himid and Cindy Sherman—which I imagine will pique a young imagination. Some of these artists, of course, had very difficult lives that ended tragically—and The Bigger Picture doesn’t gloss over this, but deals with hardship and death in a sensitive and age-appropriate way. Ana Mendieta, whose death was brutal and suspicious, aged thirty-six, is said not to have “lived to see the fame she deserved.” There are plenty of encouraging and uplifting messages, too—from the Guerrilla Girls to Sonia Boyce; and even Anthea Hamilton’s cheeky Turner Prize bum makes an appearance.

The actual art is much quieter than the stories here—each artist is represented by one artwork image, and Thapp’s illustrations bring them to life. Though the narrative is given greatest importance for the intended reader, the younger ones might find this a little wordy and text-heavy, and perhaps more pictures (or even, ahem, bigger) pictures would help them have their own responses and ideas about the art and the women who made it.

Since I have another six years to wait until my daughter can realistically read this book with me, I’ll be using it professionally myself for some of those niggling questions that I’m not too sure many in the arts could claim to know offhand. In particular, the glossary of art terms summarised in the back will be very useful, not least for finding out exactly what “mixed media,” actually is.