I first saw Bosco Sodi’s colossal studio in Red Hook, Brooklyn, some six or seven years ago. It was the summer after I graduated from art school and, like so many others, I was bouncing around New York, freelancing as an art handler and studio assistant. This is when I found myself helping Sodi’s assistant to fabricate the massive, custom crates used to transport his paintings. The studio itself feels as spacious as an aeroplane hangar, and it sits on a pier that extends over New York Harbor. As you approach the front door, the Statue of Liberty stands to your right at such close proximity it’s as if you could carelessly skip a rock and hit it. After all these years in New York, it remains the best view of the statue that I’ve ever seen.

The studio floor is a rough, multi-hued terrain reminiscent of a sci-fi film. It rises and falls with the same vibrantly coloured, earthy texture found in Sodi’s paintings; a result of the artist creating the works as they lie horizontally on the ground (think of the famous floor of Pollock’s East Hampton studio but, instead of dripped paint, it’s scattered mounds of Sodi’s ineffable colours and textures). Two Porsches sit parked in the back of the workspace, one—a red 1967 Porsche 912—has a sign in the rear window, advertising it for $55,000. “I’m selling that one,” says Sodi. “It’s too difficult to maintain.”

The surfaces of his paintings are made primarily from a mixture of sawdust, glue, raw pigments and latex; an alchemical combination that together forms a vibrant, rough plain that recalls extraterrestrial topography as much as it invokes the dry landscape of the artist’s native Mexico. As the mixture dries, deep cracks form in it, something Sodi has learned to embrace over the years.

In 2002, he visited an exhibition of works by Georges Braque

, the French painter who, along with Picasso, shaped cubism in the early twentieth century. He bought a show catalogue as a gift for his mother. “I got it because my mother loves cubism,” he tells me, “I was reading it on the train back and I read that Braque, when he wanted to give texture to a painting, would use sawdust mixed in his oil paints. Before that I was using marble dust and sand and other typical things that artists use. So I began experimenting with sawdust. At the beginning I was very shy, just using a little bit, and then one time I was at my studio and I put too much in the mixture. When I was leaving the studio with my kids (they used to come by and we would go to the beach; these were the good old times in Barcelona) I dropped the bucket. They were eager to leave so we left the mixture on the floor. That was Friday, and when I came in on Monday, it was this huge chunk of material with cracks. It was beautiful.” Today, Sodi maintains studios in New York, Barcelona and Mexico. He sources his sawdust from local shops, while his raw pigments stem from countries all over the world, such as Morocco, India, Mexico and Japan.

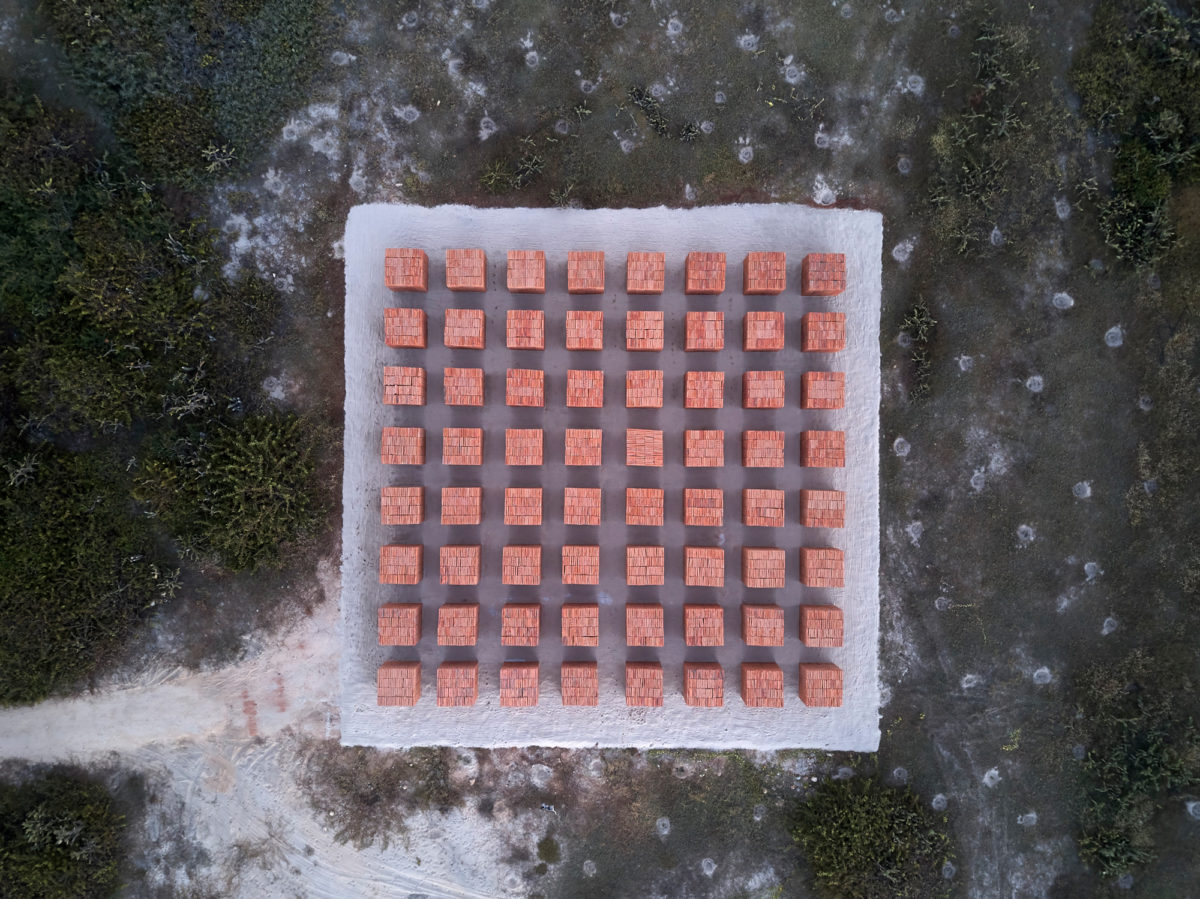

Installation view of Bosco Sodi, We are the Garden, the Garden Is Us. February 3–April 1, 2020. Botanical Garden of Oaxaca. Photo by Sergio López. Courtesy the artist and Kasmin Gallery

“You know how Anish Kapoor bought the rights to a pure black?” he asks me as we discuss the pigments. “Well, I got a better one.” He pulls off the protective tarp that has been hanging over one of his paintings and shows me a massive canvas with a black so deep that it hardly reflects light, vacuuming it up like a hole rather than being articulated by it. “In pure pigment, these absorb 99.5 per cent of light,” he says. “When you mix it with latex, like I do, it absorbs maybe 88 per cent.” At the time of speaking, the black paintings are packed up and will soon be heading to Spain by boat for an exhibition at CAC Málaga.

Portrait by Don Stahl

In 2014 Sodi founded the Casa Wabi Foundation in Oaxaca, a non-profit artist residency programme named after the Japanese term wabi-sabi: meaning an outlook that embraces chance and imperfection. “I have always tried to be very open to accidents, non-control and chance. I try to embrace that in my practice,” he says of the name, adding, “to paint or make sculpture, it’s therapy. It would be very boring to come in and do everything the same. It would be better to go to an office every day from 9 to 5. I try to implement the mindset and to be open to the accidents.” In addition to hosting large exhibitions and providing the visiting artists with housing and studio space, Casa Wabi requires that its residents carry out projects with the local communities. “The artists don’t host painting workshops or little things like that,” he tells me. “They have to propose something with substance and something that will really make a change. Maybe not an immediate, perceptive change, but something for the future.”

- Installation view of Atlantes, 2019. Oaxaca, Mexico. Photo by Serigio López. Courtesy the artist and Kasmin Gallery

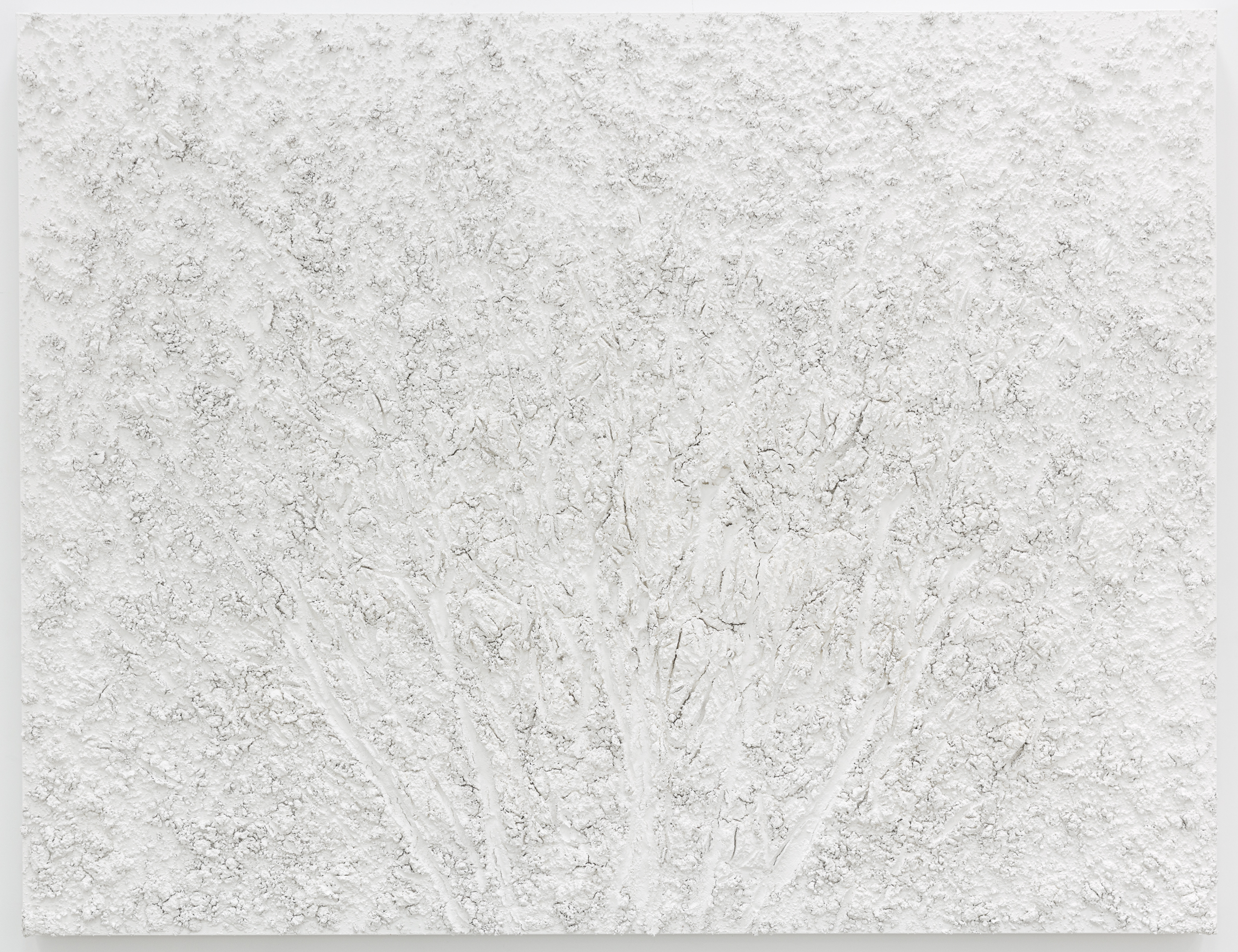

For his current show at Kasmin, Sodi is exhibiting a body of new white paintings. These works were executed recently, and came out of a fascination with a Joan Miró painting that he saw in Barcelona. (Sodi and his family spent ten years living in Barcelona, moving there initially so his wife could pursue a master’s degree in economics). The Miró paintings, Peinture sur Fond Blanc Pour la Cellule d’un Solitaire (Painting on White Background for the Cell of a Recluse), which are housed in the Joan Miró Foundation in Barcelona, are a series of white canvases with a single black line running through each. The Spanish artist painted them as a septuagenarian in the late 1960s. “When Miró was able to reach this amazing simplicity, he was beyond everything,” says Sodi, who would visit the Miró museum every month or so during his years in Barcelona. “I love those paintings. You have to be old to make those kinds of paintings, when you don’t care about anything, you know?”

“You have to be old to make those kinds of paintings, when you don’t care about anything, you know?”

For this body of work, the Miró influence met another longstanding inspiration: nature. Sodi and a friend drove around his Catskills property (where he spends his weekends) looking for trees with well-articulated, fractal-like limbs. First Sodi tried whipping the branches against the snow on his property to see its effect, then he brought them back to his Brooklyn studio. There, he applied his mixture involving sawdust and pigment (white pigment, this time) but rather than allowing the material to dry and crack naturally, as it is inclined to do, he whipped it with the branches when it was still wet. When I tell him I can’t help but think of the Abstract Expressionists standing over their canvases, Sodi nods, telling me, “It’s physical, and there’s an exchange of energy between the painting and the artist.” In addition to the long ruptures the branches make in the material, bits of twigs get stuck in it by chance, which remain embedded as it dries and become part of the work.

“I’ve always had a connection with nature. When I was young I was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder, hyperactivity, etcetera; I found ways of calming myself which included painting and being in nature. Relating to people can be difficult for me,” he explains, after I prod as to where this desire to re-present and work with organic forms comes from. “When I was young I used to go to my grandparents’ house in the forest every weekend. A few years ago we bought a house upstate. It is a dream to go there; we have goats and chickens and a small lake. When I’m in New York, we go every weekend.”

At the time of our meeting, Sodi has just returned from a long trip to Egypt with his family. The idea came after the artist encountered a Richard Serra interview, in which he noted the influence from ancient tombs. Sodi shows me a blue and white painting that is in progress; the work is lying horizontally on four buckets as it dries. This painting was inspired by the ceilings of Egyptian tombs, which are painted to resemble the sky so that the dead may find their way upwards towards the afterlife.

I ask him, with a practice that feels so earthly and distinctly rooted, and yet with a lifestyle that appears so sweepingly nomadic, when is he the happiest? “After the last few weeks of travelling, I need to come back to paint. To reconnect and relax, otherwise I have too many things in my mind,” he says. “For happy moments? I love to be with family, I love to be in the Catskills, but I also love to be in Casa Wabi, and to be with my friends.” He nods, adding, “There are a lot of happy moments.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 43

BUY ISSUE 43