What is Boy.Brother.Friend?

Boy.Brother.Friend is a new magazine that sets out to explore modern masculinity in the context of the black creative community. It takes a multidisciplinary format, bringing together fashion, art, poetry and theory across more than two hundred pages. The title nods to the notion of masculinity as a plural and not a singular: “There are so many different men that we have encountered as friends and in family life, and there’s a lot of work to be done for them to feel fragility and other kinds of emotions,” co-founder Emmanuel Balogun says. “We wanted to shine a light, and express to people who have experienced these things that we understand what they’ve gone through. It’s about what it is to be a man.“

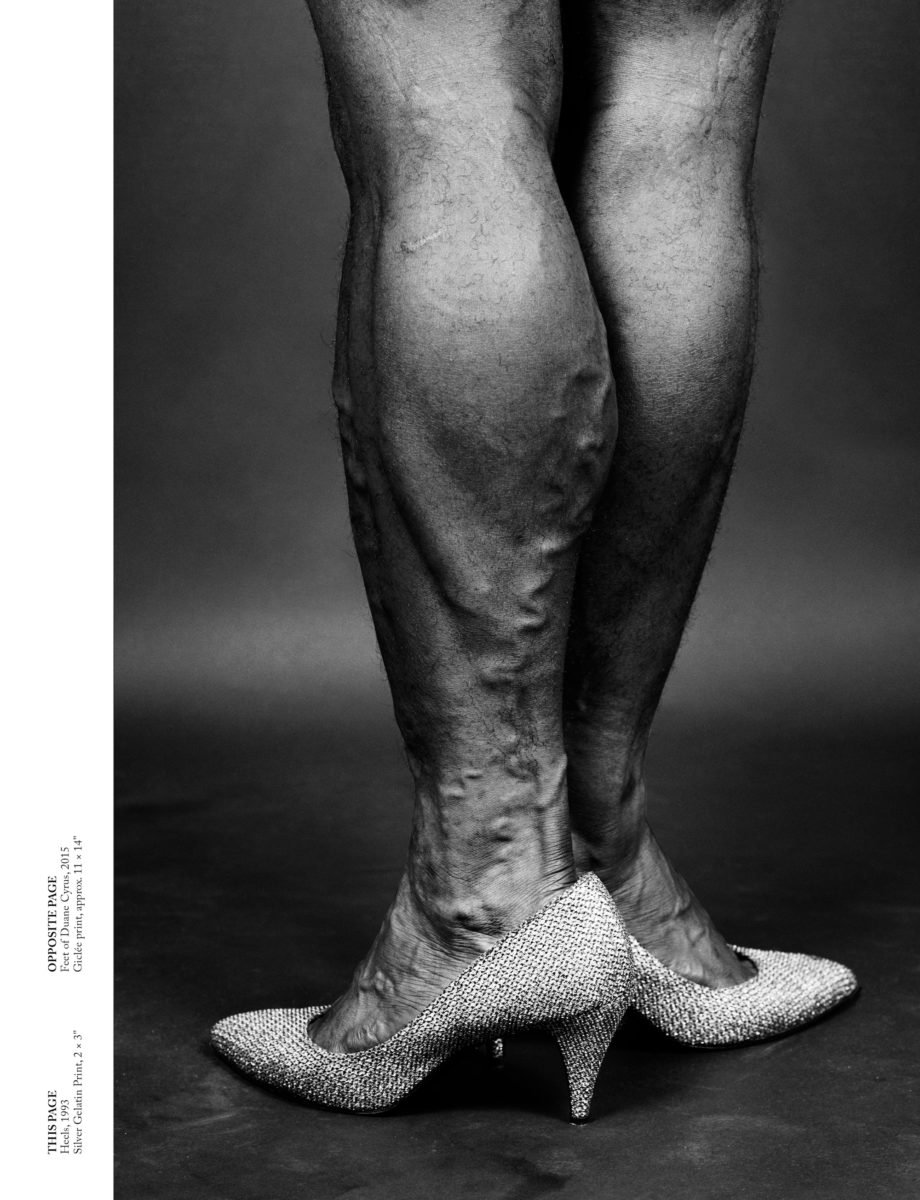

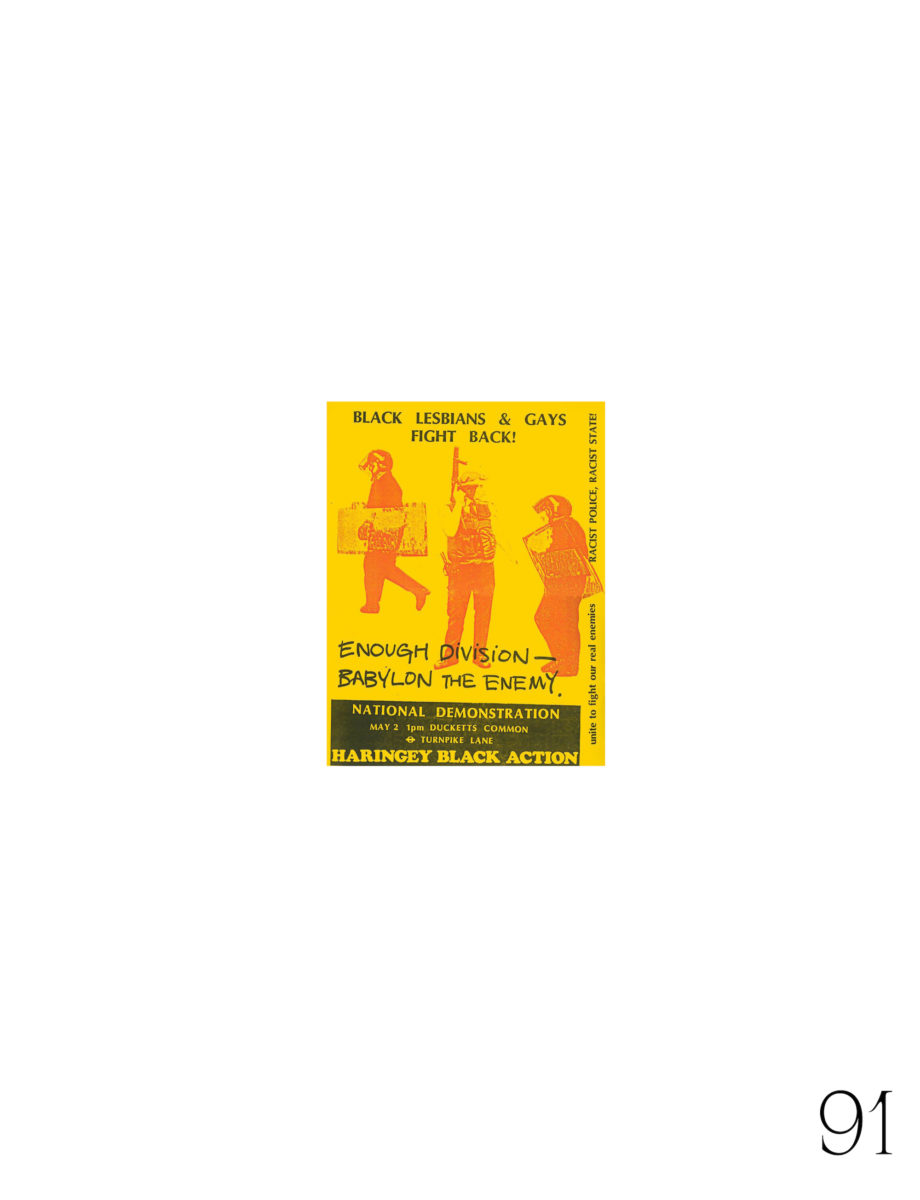

Gender is explored throughout the magazine, with representation of non-conforming and trans individuals. As Balogun points out, “Masculinity means very different things in different societies.” Boy.Brother.Friend also takes a cross-generational approach, with contributions from the Black British queer archive Rukus! Archive, and text-based affirmations that recur throughout from writers including Stuart Hall and bell hooks. The first issue is themed around the subject of “discipline”, touching upon everything from family and the environment to community and control.

“Fashion is an image-driven focus, and we thought it would be useful to process that through ideas that might change how you read that image“

Who’s behind the magazine?

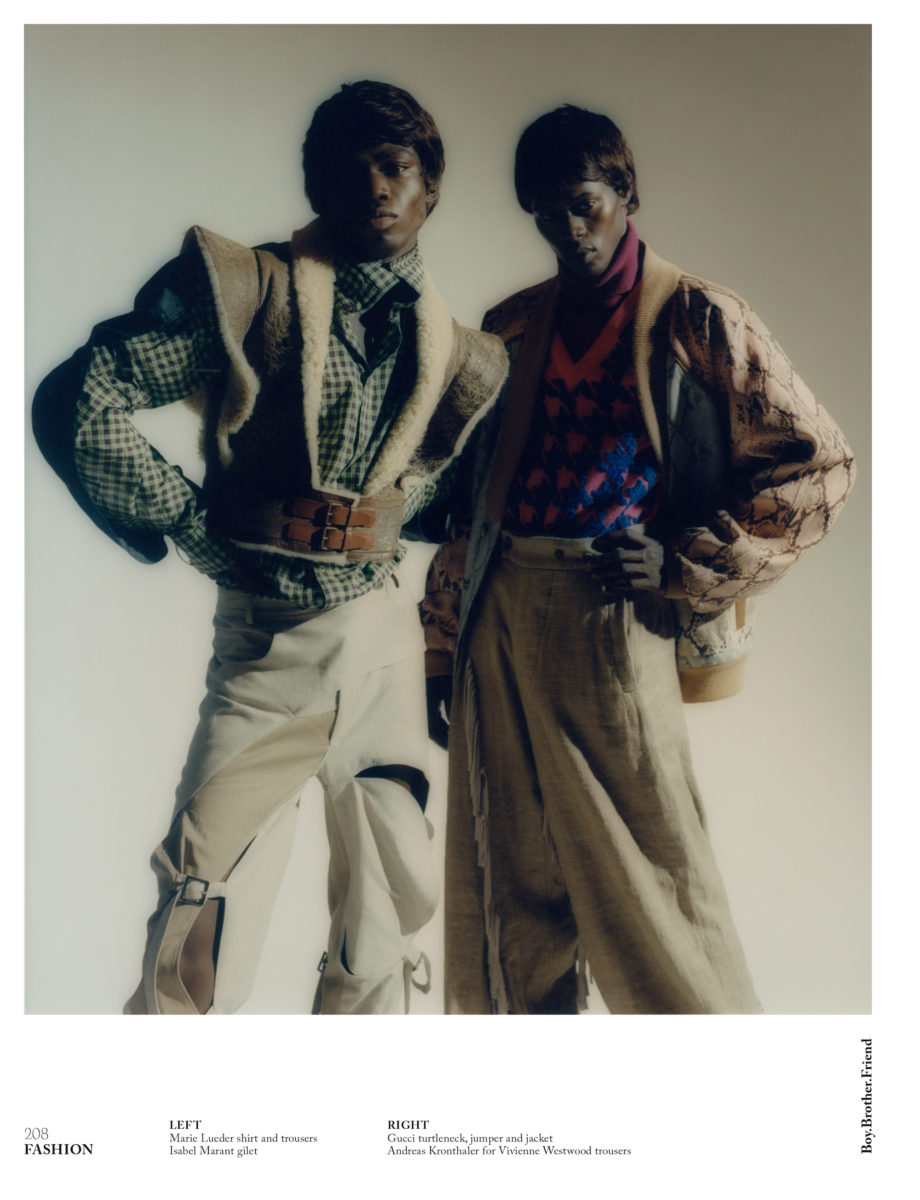

Started by two friends, stylist Kk Obi and writer and researcher Emmanuel Balogun, Boy.Brother.Friend emerges from an earlier zine put together by Obi in 2017. Three years on, the pair have come together to expand the publication’s remit across a freewheeling range of topics that are both personal and political. “We’ve both been making images for a long time, whether within fashion or art,” the two explain. “It was important to look at bigger themes, like developmental geographies; it has many different actions within it. We wanted to think about industries, communities and corporations, unpacking everything and flipping it on its head. Fashion is an image-driven focus, and we thought it would be useful to process that through ideas that might change how you read that image.”

Their process was a deeply collaborative one, not just between one another but with a wider community of creative friends. Musicians, artists, campaigners and poets are all given space in a series of intimate portraits—as Obi explains, he was tired of shooting fashion models. Instead, the magazine celebrates a powerful network of creative talent who are often overlooked. “All the portraits are really important,” Balogun says. “They give a way into someone’s personal world.” Also featured is Algerian-born artist and photojournalist Mohamed Bourouissa, who focuses on power dynamics in urban peripheries, and Mark Corfield-Moore, who uses weaving to interrogate his Thai heritage.

Why should you read it?

This is a magazine unafraid to challenge and embody the politics of representation. At a time when galleries, museums and magazines make long overdue promises to diversify, Boy.Brother.Friend couldn’t have emerged in a more urgent moment. “This kind of representation doesn’t really exist in the fashion and art landscape, and this is our existence,” Balogun says. “There was always the thing of not being able to see others like yourself in the media that we both love and admire, so we were trying to bring those things together in a way that we felt was representative of our voice.” However, they point out that they are keen to move away from words like “visibility”, which draw attention to a broken system—”it namechecks the institutions that haven’t seen you,” Balogun argues. Instead, they are interested in the concept of post-visibility.

“We came together and created a response to the fact that we didn’t feel there was anything that represented us”

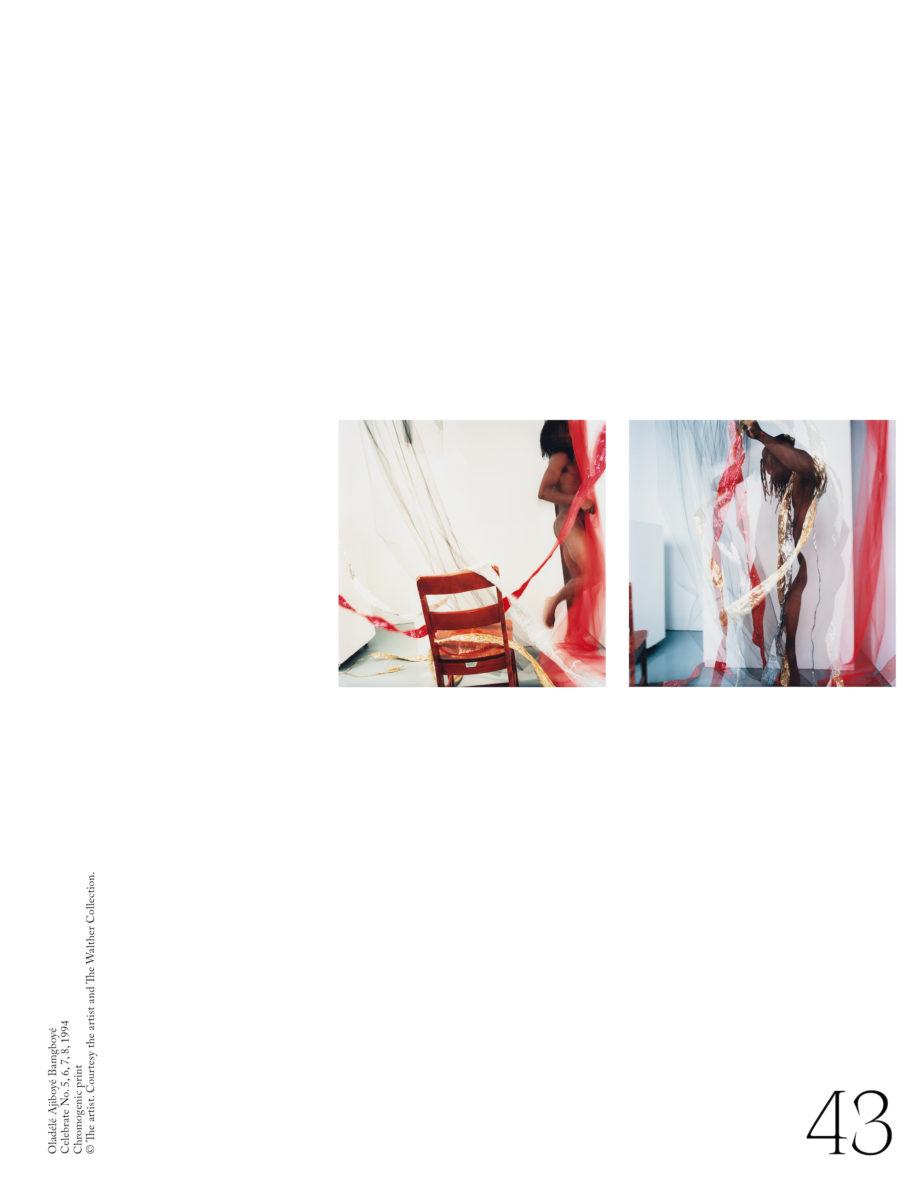

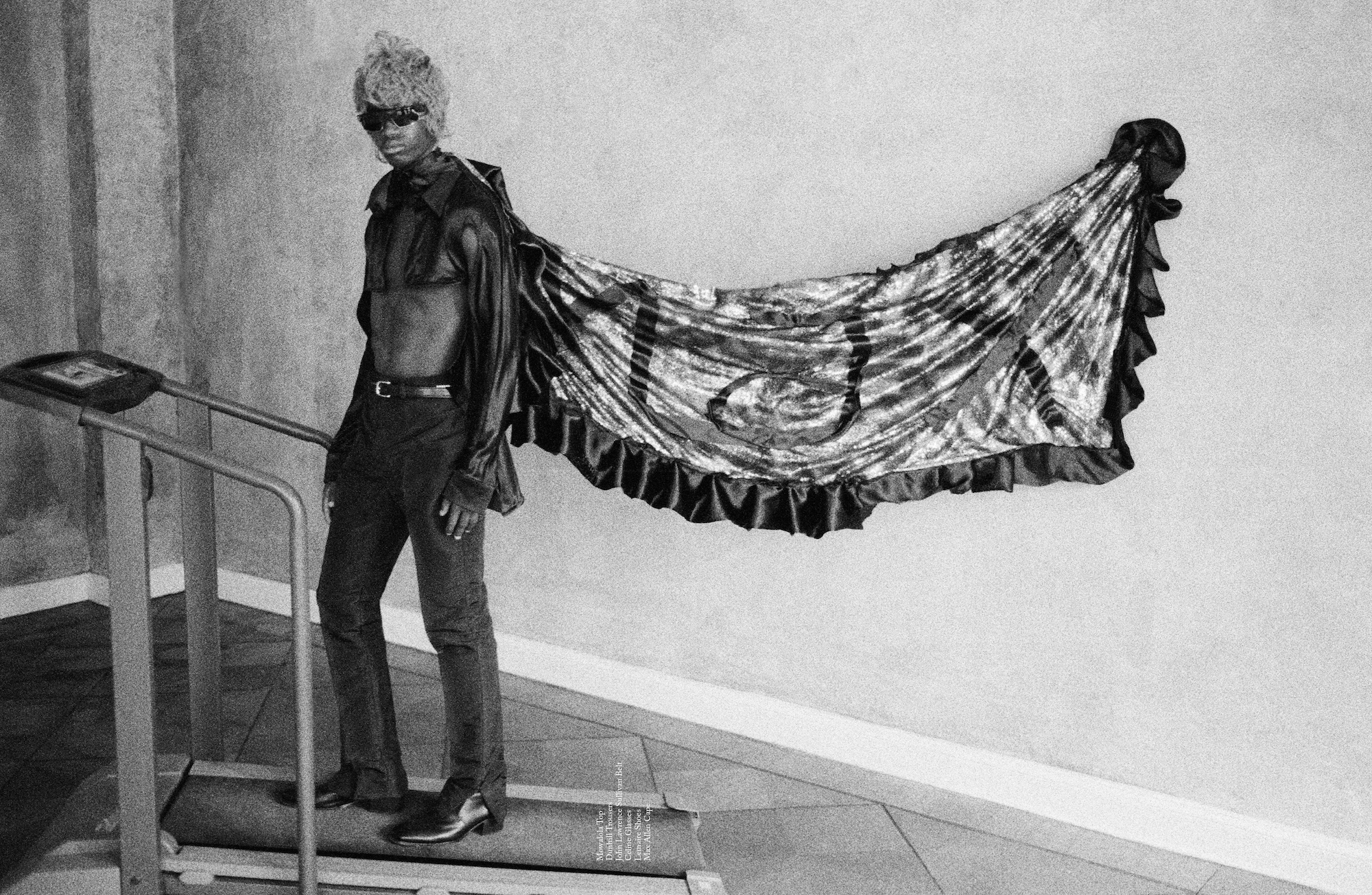

The imagery showcased in the magazine is beautiful, from tender portraits to playful shoots filled with the swooping motion of a single garment. There is an intensity to the photographs, which show beauty to be far more than good lighting and perfect teeth. Fashion is repurposed as a political force, and the magazine hums with a hunger for change. “It was all quite personal, in the context of family and the diasporic existence; it’s heavy and deep,” Obi reflects. “All the images hit a certain note within my existence, and it was important for me to capture this as much as possible.” As Balogun concludes, “We came together and created a response to the fact that we didn’t feel there was anything that represented us.”