Pixy Liao, Homemade Sushi

About a quarter of the way through Eliza Clark’s debut novel Boy Parts, the protagonist, Irina, describes her ability as a photographer. “I could train a camera on a man and look at him like a man looks at a woman; boys, too, could be objects of desire.” She takes explicit photos of men after picking them up on the bus or in Tesco. She isn’t interested in perfection; she’s after boys who are androgynous or effeminate, boys with body hair and stringy limbs. “A boy who… has the subtleties of his beauty overlooked by glamorous women, and the industries of the aesthetic.” In other words, the opposite of what male artists traditionally looked for in women.

Subverting the male gaze is nothing new. Nor, especially, is probing the politics of looking. But what Clark and several women artists are doing today is enabling us to consider not only what or who we’re looking at, but how and why. For Irina, the reason is twofold: payback, yes, but also, simply, pleasure. “I forget to keep smiling, because I’m watching him watch me… He mustn’t like being looked at, but he stares at me all the time. I like looking at him.”

What Irina does with her camera, Celia Hempton does with paint. Well, not exactly, but over the years the British artist has certainly set her sights on ordinary-looking men. Her best-known series, Chat Random (2014–ongoing), consists of often explicit portraits of men she encounters on chatrandom.com, a site that connects users around the world via webcam (often for the purpose of sexual gratification

). Typing with one hand and painting with the other, Hempton creates heavily sexualised close-ups of body parts rendered in a roughly applied rainbow palette. The sitting can end at any moment, when either she or her subject clicks “next”. Control hangs in the balance.

“The bodies they depict can be soft or stiff, up close or far away, posed or unposed, in settings erotic or mundane”

Hempton has spoken in the past about the fact that her works reflect the experience of being in a chat room, which is “often quite banal, the person quite ordinary”. Unlike selfies, these scenes are filter-free. The backdrop is usually dark, the camera angle unflattering. Body types vary enormously. The anonymous sitters are at ease, their faces cropped out and the works typically titled with a proper name and perhaps the date and location: Eddie, August 2013, Hotel Lumin, Dallas (2013) shows the subject (presumed to be Hempton’s partner, the artist Eddie Peake), lying on his front, ruddy testicles poking out beneath creamy buttocks.

Traditionally, when depicting women, male artists primped and preened their subjects to the point that they all but erased their humanity. Today, when women artists depict men, they often do the opposite, showing humanity at its most raw.

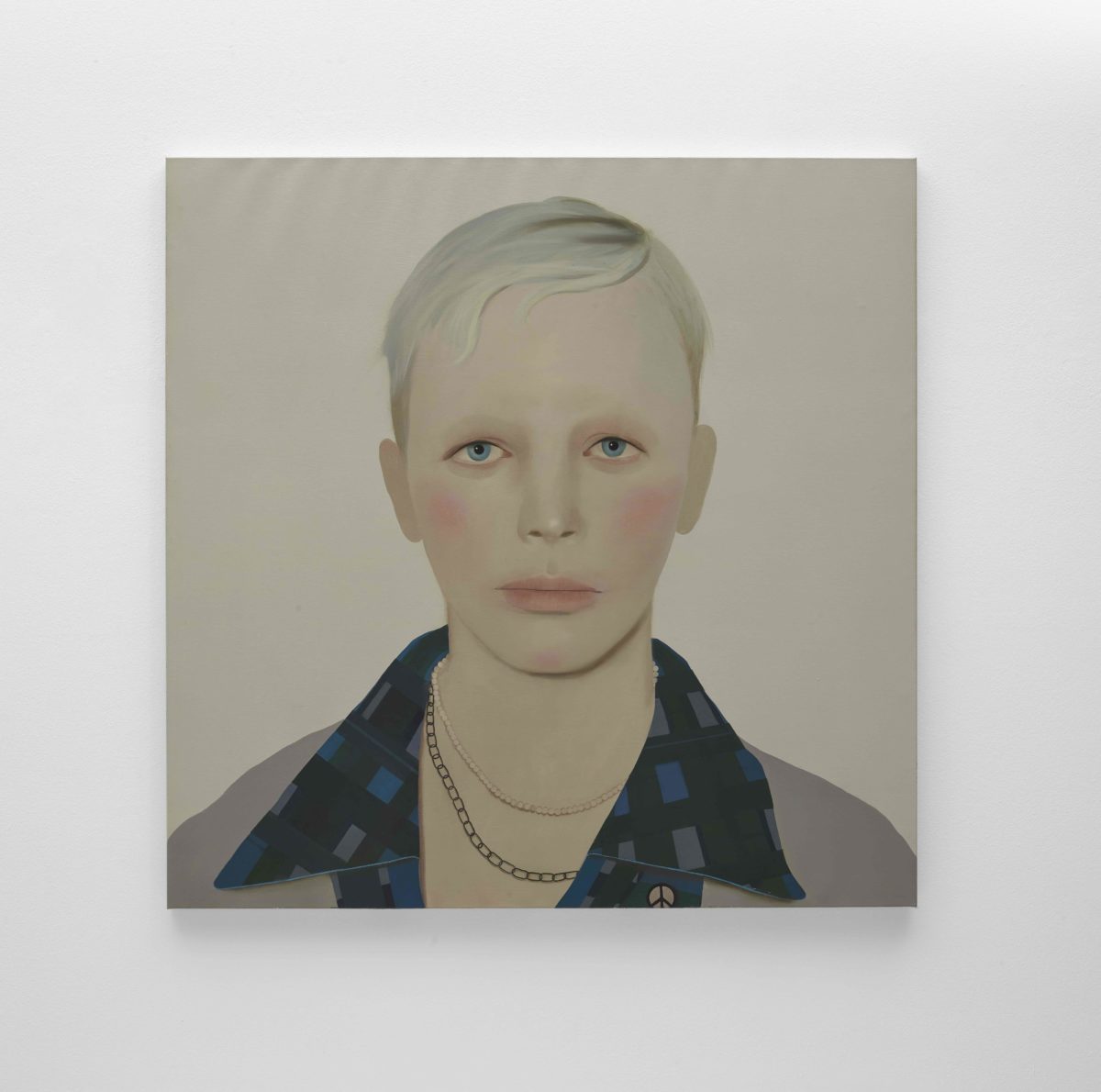

Or its most ordinary. The Paris-based Chinese artist Xinyi Cheng’s portrays androgynous young men in everyday situations: lounging, lighting a cigarette, having a haircut. Free from distractions, her softly lit and simply rendered portraits enable us to consider masculinity, male vulnerability and desire. British artist Sarah Ball’s strikingly static portraits are uninterrupted too, the backdrops muted, the faces blank. “Things are paired right back,” she says. “I remove objects that tie the subject to a specific time or place, allowing me to reveal the human person in the present.” The result is an absence that leaves room for us to reconsider who we are, or who we might be if we weren’t weighed down by cultural expectations. “I like to think that removing any sense of figurative background or scene creates an emotional space.”

Like Hempton, Ball preserves her sitters’ anonymity. Working with existing and found materials, from historical photographs to social media, she paints portraits that reflect real life—the good and the bad—back at the viewer. “I like the idea of being removed from any relationship with the sitter,” she says. “There’s a distance between myself and the subject and that allows me to expand on the purely figurative.”

- Sarah Ball, Gabriel (left), Timothy (right), 2020. Courtesy the artist

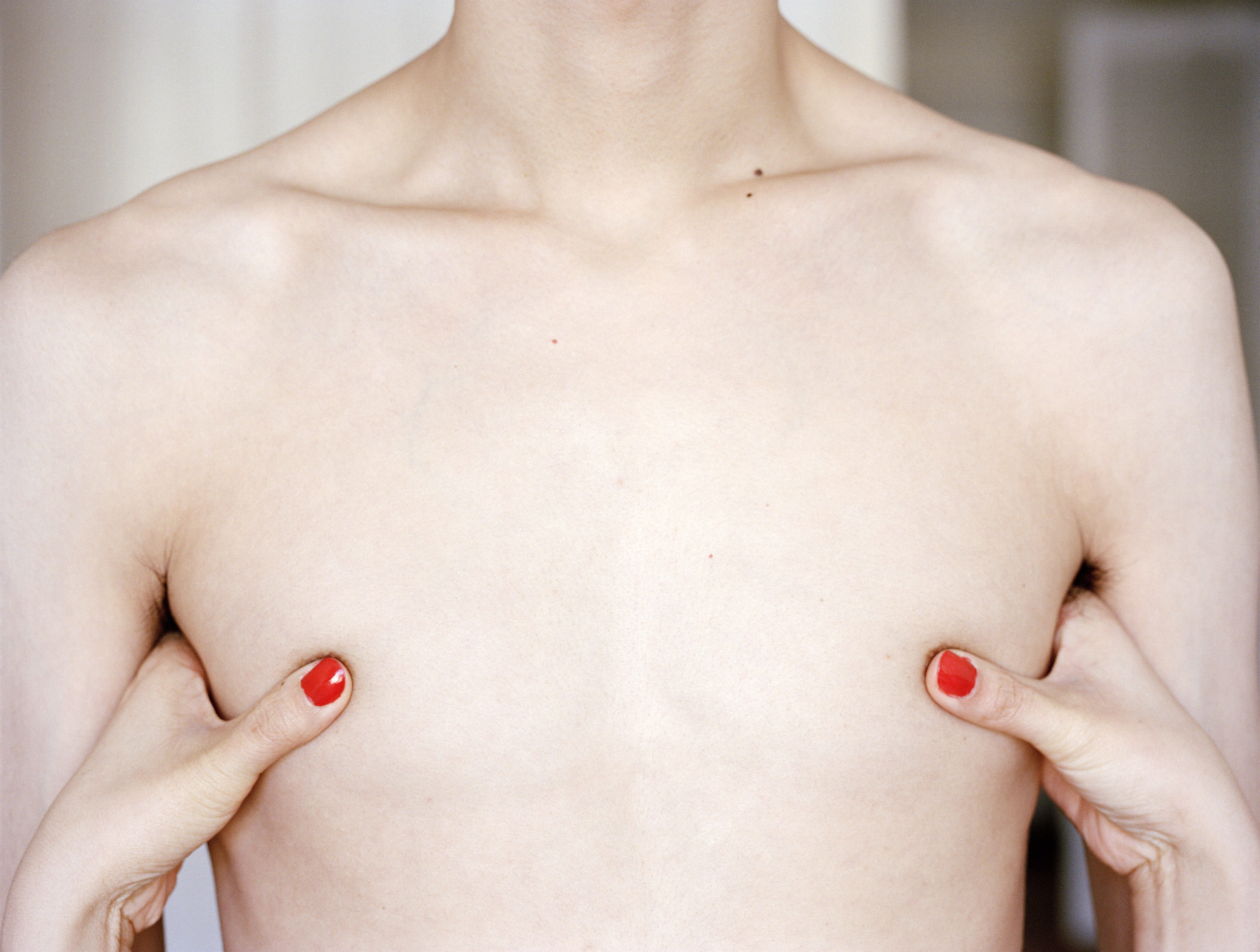

In Boy Parts, the relationship between Irina and her sitters is more fluid (and fraught): “Sometimes the photos work better when I’m in them—a hand, high-heeled shoe, a dramatic silhouette—a powerful female presence, a phantom dominatrix.” The Shanghai-born, Brooklyn-based photographer Pixy Liao takes the artist-sitter relationship one step further. Her most notable body of work, Experimental Relationship (2007–ongoing), charts her relationship with her younger Japanese boyfriend, Moro, and their respective roles. “The new relationship inspired me,” she says. “It was very different to the kind I thought I’d have.” Studying photography in Memphis, Tennessee, far away from family and friends in China, Liao had the freedom to do what she wanted, including being the dominant party.

“I remove objects that tie the subject to a specific time or place, allowing me to reveal the human person in the present”

Liao’s playful double portraits subvert not only the male gaze, but also patriarchal archetypes in heterosexual relationships. By placing herself in control, she prompts us to question binary norms and consider the shifting lines of modern-day sexuality and gender. Some images are harsh, others tender. All achieve a sense of balance between control and submissiveness. Although Liao is the one steering each shoot, and Moro is mostly depicted as deferential, it’s often Moro who takes the picture.

Relationships Work Best When Each Partner Knows Their Proper Place (2008) set the tone for the project. In this image, Liao is fully dressed, her cropped hair skimming a ruched scarlet blouse, patent pumps peeping out beneath pinstripe trousers, matching scarlet nails. Moro’s head is shaved, his body naked except for a pair of white briefs and flipflops. Liao stares down the lens as she squeezes his nipple between her index finger and thumb; he stares at her as he, in turn, squeezes the shutter; the cable release, almost an extension of the veins in his forearm, snakes towards the viewer. “It’s like I’m remote-controlling him,” she says, a smile tugging at her lips. “I like the connection running through this image, and I think it explains how we work and also our relationship. He’s the one taking the picture, but I’m the one making it happen.”

Clark uses a sentence from Susan Sontag’s On Photography as an epigraph for Boy Parts: “Images which idealise are no less aggressive than work which makes a virtue of plainness.” History’s great male artists laid out female flesh for the erotic consumption of their mostly male audience, and what Clark, Hempton, Liao and others are doing today isn’t simply a reversal. Instead of looking at men like male artists have looked at women, they’re picking apart the idea of looking itself. The bodies they depict can be soft or stiff, up close or far away, posed or unposed, in settings erotic or mundane. They’re real, raw, ordinary. This is women looking at men.