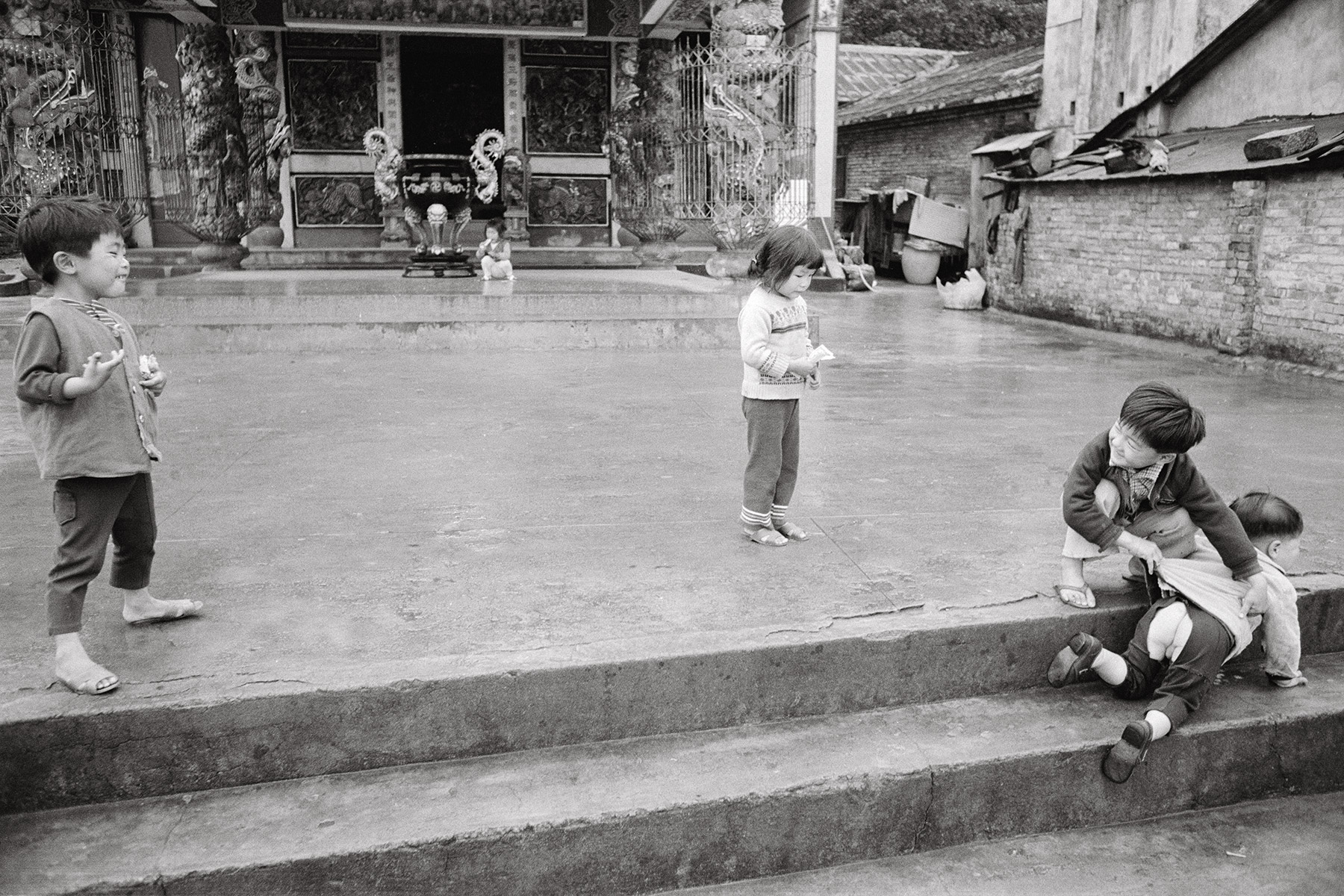

In Afghanistan, three boys sit in a dusty street, absorbed in their game of marbles. In Macao, five boys (four around the same age, one a little lost-looking on the right obviously someone’s younger brother) look serious in matching black jackets. In the USA, two boys stand in the wasteland behind a derelict building, playing in the weeds. In Malaysia, a pair of smiling shirtless boys pose for the camera, puffing their chests up to look as big as they possibly can. In India, a thin young boy, a philosopher, sits on some steps, deep in argument with an equally desiccated old man.

Roger Ballen’s photobook Boyhood is a photographic work motivated by what Walter Benjamin highlighted in his 1931 essay A Little History of Photography: the use of the medium to capture things the artist feels are about to disappear. “I worried that a boy could no longer be a boy,” Ballen writes in one of the brief vignettes which open the 1979 photobook, which is reissued this month. “That the carefree quality of boyhood,” in Ballen’s native US at least, “was vanishing amid contemporary structuring… Instead of drifting through life in a misty, half-focused, dreamlike state, they are constantly subjected to the demands of society.”

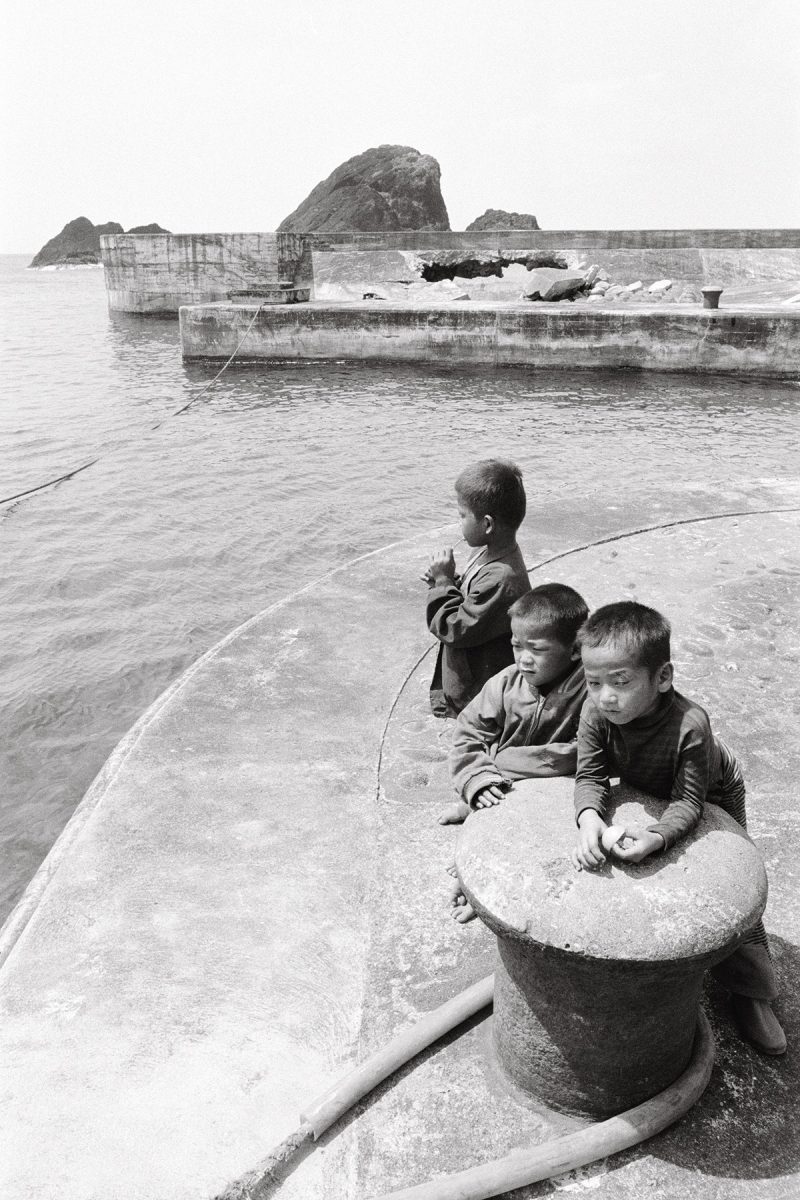

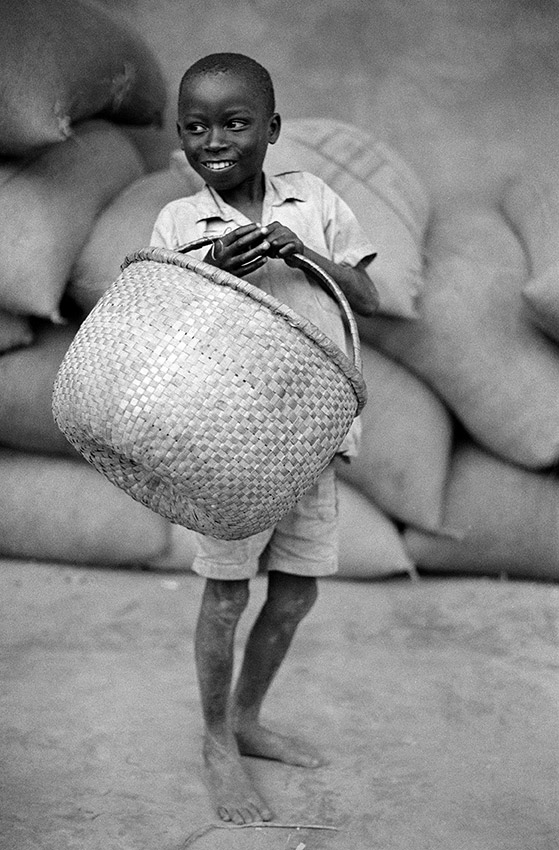

And so Ballen pictures boys, aged between five and eleven, in what he takes to be their wild state: outside of the home: usually without any adults, and usually without any girls. His vision is a cosmopolitan one. “Wherever I went,” Ballen writes, from the USA to Asia to Africa, “the sound of boys playing could easily be found.” And boys, in a way, are the same anywhere: Ballen writes of the Proustian rush back to his own childhood that he felt hearing two boys called by their mother in Ceylon. “In every group of boys there is a clown. Romeo, bully, sore sport, hothead, leader, weakling, braggart, tattletale, mope, do-nothing, nice guy, thickhead.”

“I worried that a boy could no longer be a boy. That the carefree quality of boyhood was vanishing”

What is refreshing about Boyhood, seen from the vantage point of 2022, is how naïve it is. Here we have a man, Ballen, a white, Western man, who has spent the best part of the 1970s travelling round the world, befriending and taking pictures of young boys.

Ballen offers no reflection on the fact that a lot of people, nowadays, might find this undertaking suspicious: it is simply something he has done. He doesn’t ask questions about how gender is socially constructed; about how the expectations society places on any of his subjects might be conspiring against their ability to express their most authentic individual selves; does not hand-wring about how certain sorts of boys are being failed; how they might be ‘falling behind’ girls. Ballen takes boys just as he sees them, and does not ask what his subjects might be tending towards, how they might be coaxed or trained to be something better than they presently are, or more.

“Wherever I went, the sound of boys playing could easily be found”

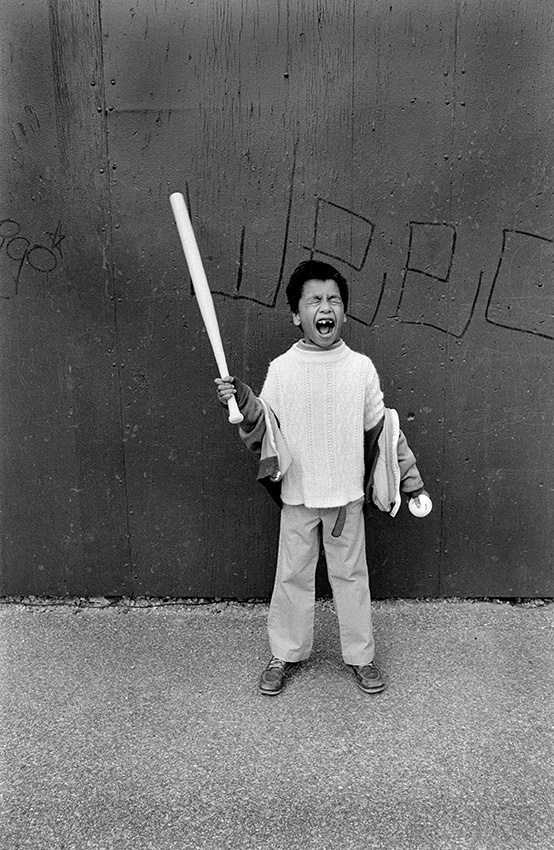

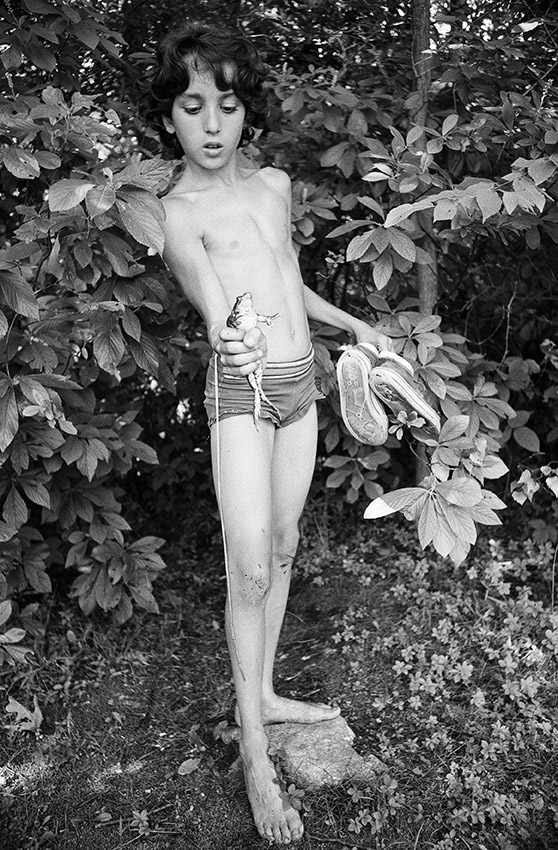

And so what is joyful about these pictures is how childlike Ballen’s own eye is. He gives us boys, in all the wonder and idleness of their play. Boys playing together, boys adventuring, boys goofing off. They do not belong to the family, or the classroom: they are creatures of the streets, the hills. Of dirt tracks, of alleyways, of beaches, and of swimming holes. Of bits of abandoned land that they might claim to build their secret bases on. They ascend precipitous walls, throw crud off bridges, and pretend to strangle their helpless younger siblings. Dudes, as they say, rock.

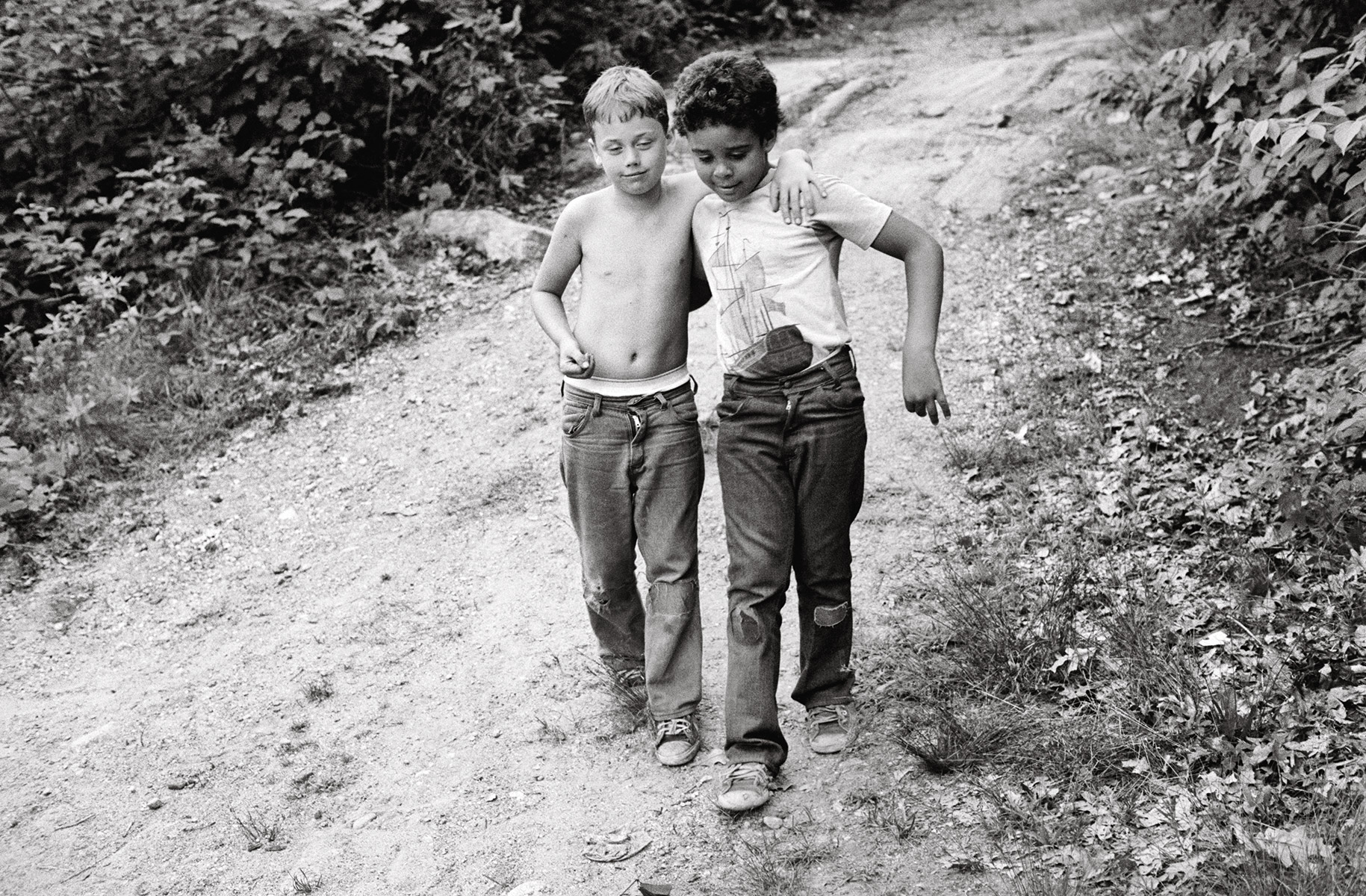

The photographs in Boyhood might be sorted into one of two major categories: pictures of groups of boys, and pictures of boys on their own. The former are infinitely more enchanting than the latter. When Ballen photographs boys standing alone, they often look a bit lost: awkward, uncertain, self-conscious, as if they have yet to grow into their own skins. It is when they are together that Ballen’s boys become themselves: fearless, chaotic, at home in the horizons of their world. This is the boyhood that Ballen is nostalgic for. It’s a nostalgia that many men, looking through this book, will share.

Perhaps indeed there is no such thing as a boy singular: ‘boys’ exist only in the plural. My own son has just turned three, so is younger than the boys Ballen pictures, and still only has a very rudimentary understanding of gender (he does not discriminate between playmates based on gender, even if the different ways that boys and girls are socialised are beginning to make relations with his best girl-friend rather fraught). But this is something I’ve begun to notice recently: the transformation that my son undergoes, when he is playing with one of his peers.

“What is joyful about these pictures is how childlike Ballen’s own eye is. He gives us boys, in all the wonder and idleness of their play”

When it’s just him and his baby sister, my son remains a toddler: dependent on, and looking only to, his parents. But then sometimes, now, he will take off with one of his male friends, and they will suddenly be boys, together. Running around the park roaring, terrorising bigger kids, pretending to be dragons. Discovering a ‘boat’ in a hole someone else has dug on the beach, steering it away from a monster. The boys are off: a law unto themselves, the inhabitants of an imaginative universe invisible to everyone else.

Who knows where this adventure my son is setting out on will one day lead, but it is wonderful to watch, for now. In my son’s play, I see what Ballen saw in his own subjects: myself. That what I once was might still be possible is a beautiful thing. And so it is clear to me that what Ballen has crystallised here is a sort of hope.

In the 1970s, Ballen may have already feared that boyhood was disappearing, and with good reason: a combination of new technologies and over-protectiveness has meant that there are certainly fewer children playing on our streets today. But as long as there is a pack, there will be wolves; and as long as there are boys, there will be boys. Boyhood is a testament to this.

Tom Whyman is a philosopher and writer who lives in the north east of England

Boyhood by Roger Ballen is out in September (Damiani)