When Legacy Russell describes her upbringing in New York’s East Village in the 90s, she recalls a landscape of punks and drag queens, people who threw into sharp focus the conscious construction of identity. As a shy kid, and a child of the internet, she experimented with her own identity in chat rooms. Offline, she was—and is—“Black, female identifying, femme, queer”, but online she found that she could be anyone she wanted to be, “slipping in and out of digital skins”. So began an interest in digital selfdom that has carried through to her work as Associate Curator of Exhibitions at The Studio Museum in Harlem and as the author of Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, her first book, released with Verso this September.

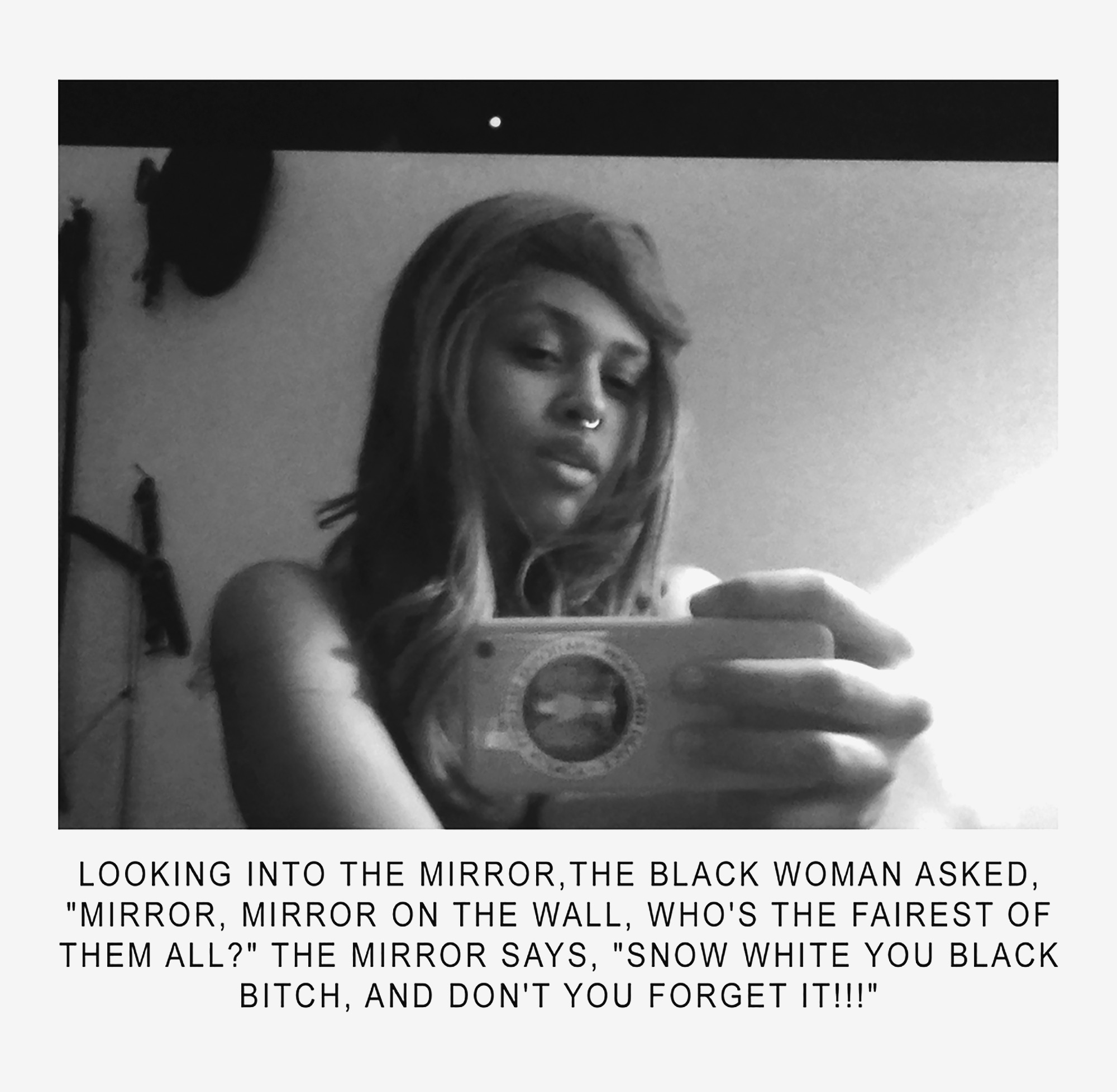

Glitch Feminism explores how online spaces can help us elude the limits of the body and, more importantly, the ways in which it is read in society. Russell does this particularly by looking at the work of queer and black artists who use digital avatars or other digital technologies to perform new identities that break away from the confines of binary gender. “With physical movement often restricted, female-identifying people, queer people, Black people invent ways to create space through rupture,” she explains in the book’s introduction. “Here in that disruption, without collective congregation at that trippy and trip-wired crossroad of gender race and sexuality, one finds the power of the glitch.”

As well as providing a new approach to the work of contemporary artists such as Boychild, Juliana Huxtable and Victoria Sin, Glitch Feminism presents a well timed strategy for celebrating “the glitch”—which is something traditionally thought of as “an error, a mistake, a failure to function”—as a “vehicle of refusal, a strategy of non-performance” that can be both liberating and expansive.

In

Glitch Feminism you talk about how your early days online influenced your interest in how digital spaces and identities—when used in certain ways—can liberate us… what else influenced this interest?

As a young Black queer woman who didn’t always feel like she fit in, I found a real community online. I was morbidly shy and anxious and, for kids like that, finding your voice out in the world can be super difficult. The internet was a place where I was able to flex a little, spread my wings, and be super weird. So part of this is me writing for those folks who share in that lived experience, too.

I think I’ve also been influenced by watching creative Black spaces and queer spaces—especially sites of nightlife and performance—become increasingly vulnerable, and even erased, across so many cities in the world. It is not a coincidence that these same communities have come online to collectivise and think through how to innovate through this erasure and rebuild with care. Just as mapping these places and the historical presence of performance practice in them is an active and important act of archiving our culture and legacy, thinking through how we can do the same for the Black and queer creative communities online feels essential. That’s something I wanted Glitch Feminism to do.

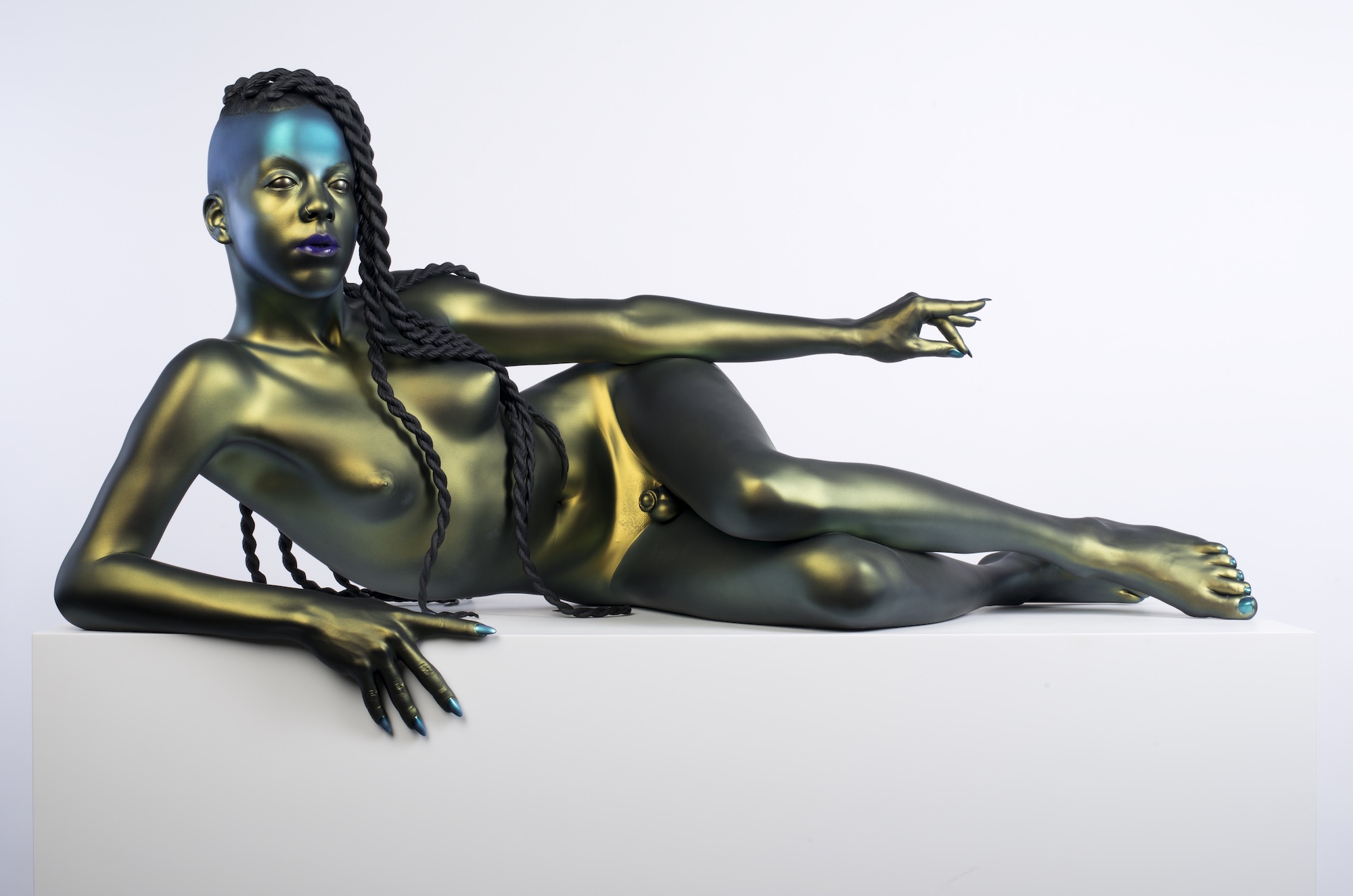

Frank Benson, “Juliana,” 2014–2015, 3D Rendering. Courtesy of the artist, Andrew Kreps Gallery, NY and Sadie Coles HQ, London

“When we look at the history of cyberfeminism, we see that white, cis-gendered, white women are prioritised and made visible in this narrative”

Glitch Feminism is described as “a new manifesto for cyberfeminism”. You talk in Glitch about how you have found cyberfeminism to be exclusionary and flawed—in what ways?

I think there is often a romantic notion of “the digital” that makes this assumption that it is art history that is flawed and exclusionary, but that somehow cyberfeminism still has roots that are emancipatory and filled with this intersectional inclusionary potential. It just isn’t real. Cyberfeminism is a part of art history, regardless of whether people are ready to talk about that or not. People are still surprisingly antagonistic about welcoming the digital into the art historical canon; they’re so obsessed with an object-oriented ontology that they keep resisting this idea that the digital is a living breathing organic material that has the capacity to do so much as a creative medium.

Still, when we look at the history of cyberfeminism and how it is told, we see over and over again that white, cis-gendered, white women are prioritised and made visible in this narrative. People like Donna Haraway, Faith Wilding, Sadie Plant, Linda Dement. I can’t stress enough how important it is to really think on why it might be that certain faces and voices dominate these narratives and, too, to consider further how the history in and of itself can be actively decolonized.

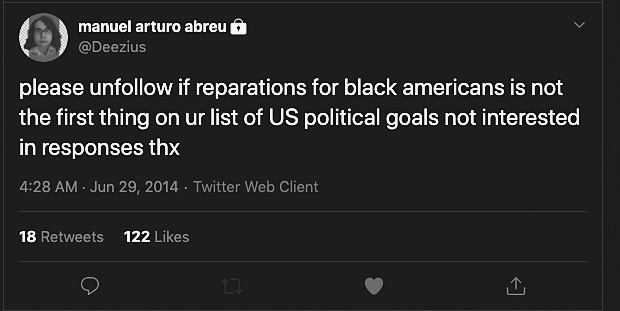

Digital technologies are an inherently Black and queer material; therefore Black people and queer people should be dominating rosters of exhibitions and projects where these stories are being told. Glitch Feminism looks to bring together a chorus of thinkers across generations and methodologies to bend space and time together, allowing Octavia Butler, Lucille Clifton, Essex Hemphill to share and hold space right alongside American Artist, E. Jane, manuel arturo abreu, Juliana Huxtable and Victoria Sin as an exercise in a speculative imaginary, a collective reshaping of the history of cyberculture, pushing it further toward a future that necessitates it.

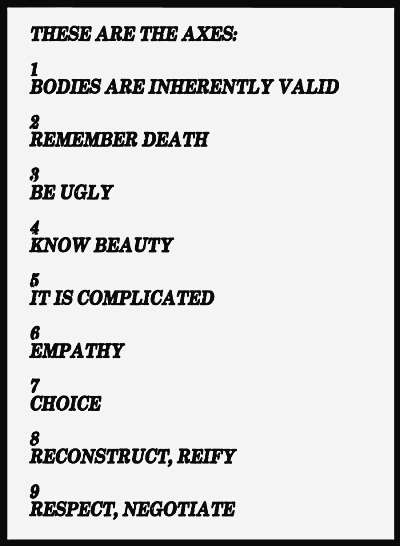

The book is structured around mantras, such as “glitch refuses”, “glitch is cosmic”. How did you land on this format?

Manifestos allow for a certain kind of clarity, drive and purposefulness when setting forth specific demands. The structure of a manifesto actually lends to a lot of range; it supports a bigger imagination than a traditional narrative text. As manifestos typically aim to reach toward a world as it should be, it means that within the structure of the manifesto we can dream beyond the confines of what we might be limited by in our day-to-day. The way the book is structured makes that dreaming possible.

It does! But it is just also a great guide to amazing contemporary artists working in or around the digital sphere. I love that you talk about Rindon Johnson’ work and the question it often presents of “how useful or helpful is it to have a body?” It’s a question you’re also turning over. Did you find artists to fit your trajectory, or did the artists you discuss shape your trajectory? Or is that impossible to answer?

I appreciate this question because—yes—it brings together a lot of incredible people doing important work. This book has been a labour of love, working on nights and weekends and early mornings over a period of years. It’s a brief and furious read but I feel like in the process I have written ten books [laughs], because that’s how deep and dense the experience of birthing this has been.

From the very beginning E. Jane, manuel arturo abreu, and Shawné Michelain Holloway have been artists I have celebrated as embodying “the glitch” as a radical site and material. Curator writer and artist Anaïs Duplan and his poetic work was someone I was thinking about as I considered the possibilities of language, and how language in and of itself should be pushed to do wild things, as a means of expanding some of the questions Glitch Feminism proposes.

“Digital technologies are an inherently Black and queer material; therefore Black people and queer people should be dominating rosters of exhibitions”

In some ways Glitch Feminism

is very informed by identity politics and is strongly intersectional—it feels motivated by your experience as a black queer female, for example—but it is also exploring how and why we might reject and elude fixed or “legible” identities. You quote James C Scott: “Legibility [becomes] a condition of manipulation”. It’s interesting to me that these approaches coexist…

Identity and legibility can definitely coexist; they’re not a binary. The first is, in an ideal and empowered sense, how one might claim for or define oneself. The latter is about how someone else defines you, and surfaces questions of agency as well as assimilation. Legibility is a coercive tactic, and asking people to make themselves legible is in and of itself a violence.

My claiming with pride my blackness, queerness and femme-ness is not to make myself legible to someone else, it’s to engage with care and complexity these parts of my being, and to demand for a more generous and expansive vernacular that allows for range and variance across this being that rejects the notion that to be “valid” we have to be “readable”, and if we are not “readable” then we are by default otherised, marginalised and made vulnerable—that shouldn’t be the case.

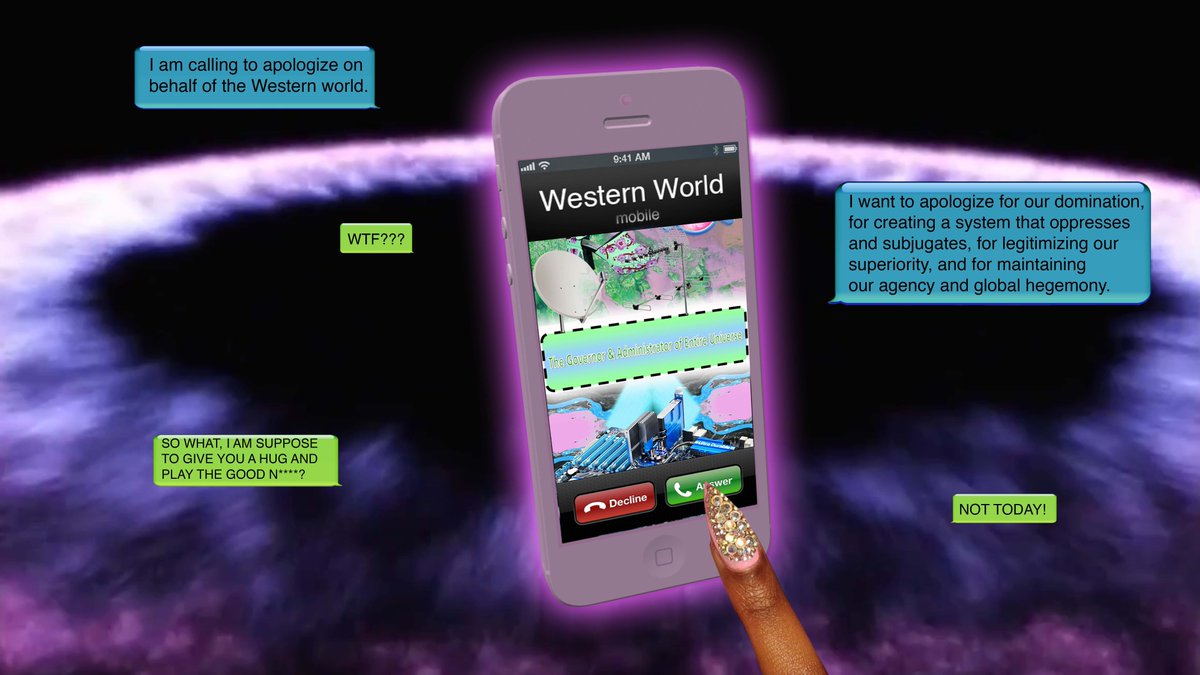

Tabita Rezaire, “Afro – Cyber Resistance,” video still, 18:26, 2014. Courtesy of the artist

The book is (hopefully) coming along at a time when cis/ binary gendered people are engaging more with trans/ nonbinary issues, and when more white people are thinking and talking about racism. What do you personally want people to take from the book?

Recently I had a journalist ask me if I was concerned about whether this text could be interpreted as a “gesture of violence and or aggression”. I found this to be so difficult to stomach given the troubling premise it puts forward, but also was glad to hear it, in a way, because it makes plain what is really wrong with this moment in history. It’s important to remember: refusing violence against us is in no way a “violent” act, it is not an “aggressive” act—it is our right. Glitch Feminism speaks to that refusal.

As a text, it is asking people to celebrate and find joy in the creative contributions of a cyberculture and cyberfeminist art history, to be part of that course-correcting and demand more, but also to embody the glitch, to become the disruption as a strategic act and a way of committing to loving ourselves and one another more fully, bearing witness to one another and holding space for one another, just as we are. In this moment, perhaps more than ever, we are collectively coming into awareness that the breaking of what is already broken can operate as a catalyst towards greater change in the world. My hope is that people can think about what it means to glitch or break systems as a radical act of refusal.

“We are collectively coming into awareness that the breaking of what is already broken can operate as a catalyst towards greater change in the world“

And finally, I would love to know what you have been reading recently, as well as where you’d send us for further reading after Glitch Feminism.

I would say to follow the threads in the book, it’s a choose-your-own-adventure, really! There are so many incredible folx to spend time with within the pages of Glitch Feminism. My hope is that people will spend as much time in the footnotes and citations as they do in the body of the text, as every part is intended to be discussed, shared and engaged with.

Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism