Working collectively is often now interpreted as a form of resistance to the perhaps hackneyed ideal of the individual genius, but the impetus for artists to create and author work together has a long history, as Ellen Mara De Wachter explains.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 29.

Collective practice is an increasingly popular approach for artists making work today, whether that collaboration takes the form of an intimate duo or a larger group operating under an assumed name. It is also getting unprecedented attention from curators and audiences: the latest editions of the Venice Biennale (2015) and the Whitney Biennial (2014) showed the largest percentage of collaborative art practices in the exhibitions’ histories, at 13 per cent and 15 per cent respectively.

It is in China during the flourishing of Buddhism in the early Middle Ages that we find the first evidence of reverence for the individual artist’s skill above that of the artisan. Artists were put on a par with poets, previously considered the pinnacle of all creatives. In the West, medieval guilds and workshops involved artists and craftsmen producing works together, usually without specific pieces being attributed to individual artisans. It was only during the Renaissance that the uniqueness of the solo artist’s hand began to be prized both culturally and financially, with works of art coming to be valued as true expressions of the matchless qualities of the singular genius.

Fast-forward to the dawn of the twentieth century when a chain of modernist avant-gardes began to explore collective practice. Each movement in the string of –isms that included Cubism, Futurism, Suprematism, De Stijl and Dada was committed to engendering some kind of social or cultural change under a coherent aesthetic. However, every single one of these artistic groups had a figurehead: Picasso, Marinetti, Malevich, Mondrian, Duchamp.

Moreover, they authored works individually, which puts them at some remove from recent collective art practices, which happily co-author works. After World War II, the Cold War produced a split in East–West aesthetics and a parallel rift in attitudes towards collective art practice. In the US, collective approaches were viewed with suspicion, redolent of the Communist spirit of the rival Eastern bloc. Popular culture in the US instead celebrated figures that incarnated the mythology of the lone genius: for instance, Jackson Pollock, an avant-garde artist with a challenging aesthetic, who nevertheless became a household name. In the Eastern bloc, art was equally influenced by state policy, except in this case artists were expected to work together in state-sponsored workshops. In spite of the collective labour conditions, the imposition of the official Communist style—Socialist Realism—stifled experimental collaborations and heavily determined artists’ work with rigid requirements over subject matter, style and technique.

In the 1960s, art collectives were active in cities beyond Europe and North America, notably in Japan, Chile and Argentina, making work that responded to the post-atomic era and internal politics. In 1963, the Japanese artists Genpei Akasegawa, Natsuyuki Nakanishi and Jirō Takamatsu founded the collective Hi-Red Center, which organized happenings such as Shieruta puran (Shelter Plan, 1964) for which they created a personalized nuclear fallout shelter for each of the group’s members. For their Street Cleaning Event (1964), they scoured the pavement in central Tokyo dressed in white lab coats to mock the official campaign to clean up the city in advance of that year’s Olympic Games. Their impish critiques of social conditions in Japan prefigure the work of more recent Japanese collectives, such as Chim Pom and Kyun-Chome.

In Argentina, the Grupo de Artistas de Vanguardia de Rosario made works that were vehemently critical of the government, for example, Tucumán Arde (Tucumán Is Burning, 1968), a documentary exhibition that exposed the social and economic crisis in the city of Tucumán in the north-west of the country as a consequence of the government’s decision to close local sugar refineries.

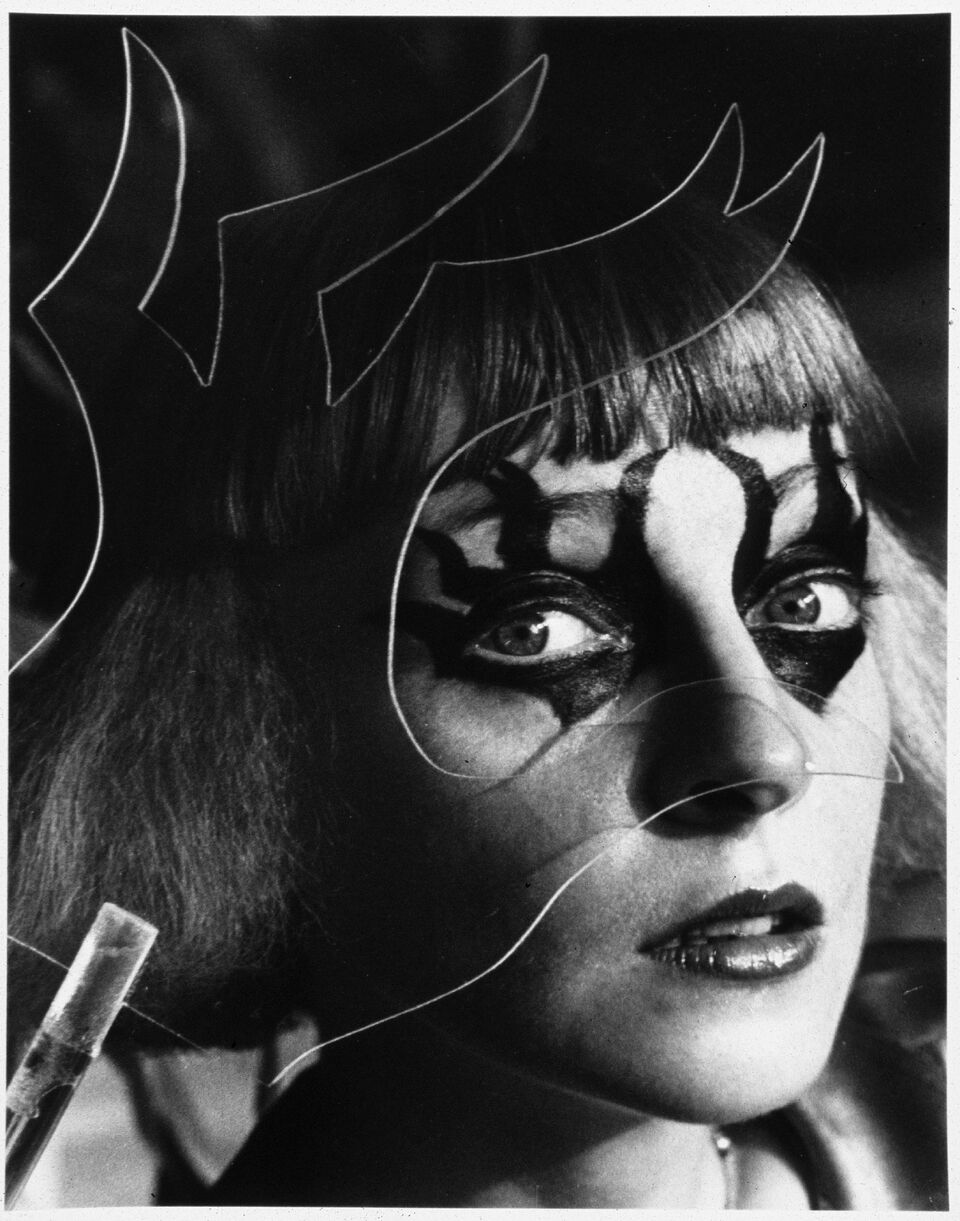

In Britain, the collective Art & Language, formed in 1968, turned its attention to the discourses and conventions surrounding art practice, criticism and theory. Over the years, some 50 people from different disciplines have been involved with the group. Art & Language’s interest in the apparatus of the art world gave way to a tendency for art collectives to engage in institutional critique. For several collectives—including the Guerrilla Girls, founded in 1985—this approach crossed over with activism addressing social inequality, sexism and the devastating consequences of aids. The early works of Canadian collective General Idea, founded in 1969 by Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal and AA Bronson, involved the persona of “Miss General Idea”, under whose guise they organized a number of extravagant events that parodied beauty pageants and trade fairs. In the face of the aids crisis—a disease that eventually claimed the lives of both Partz and Zontal—the group began making striking artworks, including the AIDS wallpaper in 1988, which appropriated Robert Indiana’s famous “love” design from the mid-1960s. The late 1980s was significant in the establishment of a number of crossover activist/art collectives such as Act Up and Gran Fury in New York, which were set up to raise awareness and challenge the US government’s negligence with regard to the spread of aids.

In the 1990s, postmodernism was evident in the work of collectives that ironized institutional and corporate strategies by treading the line between consumer enterprise and critical art practice. In New York, Art Club 2000 was initiated in 1992 by the art dealer and impresario Colin de Land along with seven of his students from the Cooper Union School of Art. The group cast a sharp look at the relationship between advertising and desire, in particular with regard to clothing and interior design. Their photographs were pastiches of lifestyle features from glossy magazines, with Art Clubbers wearing outfits from the Gap or hanging out at the Conran Shop. Bernadette Corporation, started in 1994 by Bernadette van Huy, John Kelsey and Antek Walczak, also played with fashion and branding to create its own line, and to put on exhibitions that rewarded visitors with a serious dose of ambiguity. More recently, the trend forecasting group-cum-art collective K-Hole was set up in 2010 in New York by Greg Fong, Sean Monahan, Chris Sherron, Emily Segal and Dena Yago, young arts graduates who had experience in the trend and marketing industries and whose work involves publishing bona-fide trend forecast reports.

In 1990s London, the collective bank—with members including Simon Bedwell, John Russell, Dino Demosthenous, Milly Thompson, David Burrows and Andrew Williamson—organized exhibitions that mocked the YBA bubble and its associated media frenzy. For their Fax-Back project, one of the most delightfully acerbic works ever made about the art world, they corrected and faxed back bombastic and ungrammatical press releases to the commercial galleries that had issued them.

Other groups founded in the 1990s focused on social, political and economic issues, for instance the Danish collective Superflex. Friends Bjørnstjerne Christiansen, Jakob Fenger and Rasmus Nielsen came together to make artworks they refer to as “tools”, which combine experimental engineering, science and technology to produce social or environmental change. Their innovative Supergas (1996) system runs on organic materials (human and animal stools, to be precise) to produce biogas that can be used for cooking and lighting in rural areas. The Indian group Raqs Media Collective was formed by Jeebesh Bagchi, Monica Narula and Shuddhabrata Sengupta. Their work involves filmmaking, curating, research, writing and editing, and in 2000 they founded the Sarai programme at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, which combines film history, new media theory, media practice and urban culture.

Working across disciplines is an increasingly common strategy for artists. The New York-based collective DIS was originally formed in 2010 as an online magazine, and has since branched out into a stock-image agency called DISimages and an online retail platform, DISown. The London-based group åyr, set up in 2014 by members from France, Italy and Mexico, has a practice that reads like a Venn diagram combining architecture, art and design. Both these collectives address online and IRL lifestyle desire and the endlessly mutating nature of aspirational living.

The collective GCC, formed in 2013 with members scattered across the globe, chose its name—an acronym that doesn’t actually stand for anything—in reference to the Gulf Cooperation Council, an intergovernmental political and economic union of Arab states in the Persian Gulf. Their work uses pastiche to critique stately rituals and administrative rhetoric, in particular in the Gulf states, with installations that often act out codified gestures or replicate environments related to diplomacy or nation-branding.

Art collectives working today often draw on a multiplicity of influences and sources, which is not surprising given the centrality of the internet in people’s lives. The accelerated circulation of images and ideas around this largely free mass collaborative platform has diluted the concept of authorship, and perhaps even taken the shine off its appeal for artists. But with free access to the internet increasingly threatened by pay walls, and the sharing economy and creative commons closely monitored by corporations seeking to maximize profit, it feels more important than ever to recognize and encourage collective practice as a means for productive critique.

Ellen Mara De Wachter’s book “Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration” will be published by Phaidon on 24 April 2017.