As memorials, symbols of resistance, and quiet acts of attention, artists turn to petals and stems to reckon with grief, legacy, and the politics of the present. Looking to this season’s exhibitions and publications, Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou explores how flowers bloom in more than decoration.

Rarely do front covers announce the contents of their pages so well as Christina Sharpe’s UK edition of Ordinary Notes. Published by Daunt Books and designed by Tom Etherington, the book immediately claims your attention with its bold black type and French-fold lemon cover. What signals the powerful prose inside, nonetheless, is a salient print of Jennifer Packer’s painting, Untitled (2017), on the outer-side of the jacket. Painted in woozy mauves, maroons and pink-tinged whites against a background of black, Packer’s floral study exudes a kind of melancholic beauty, an undiminished promise of life in the face of death and decay.

Untitled is instantly recognisable as one of Packer’s wistful and wilting flower portraits because it not only summons the signature style and sensibility of the artist but also that of the writer: the equally brilliant Sharpe. Like Untitled, Ordinary Notes is a work dedicated to moments, acts, words, impressions and forms of beauty despite the presence of death and the deadly violence of the everyday. It is a book comprised of ‘notes’ which, when gathered together like stray cuttings of flora and fauna, form a potent and impressively heady bouquet. Flowers in Sharpe’s work evoke memories in addition to serving as memorials; they embody her mother’s distinctive love of beauty – a sensibility the author has inherited and continues to cherish and practise in her own life and work.

The floral as beauty – or rather, as evidence of a ‘method’ and mode of cherishing and cultivating the beautiful in spite of the oftentimes harsh and ugly socio-political realities faced by Black individuals – becomes, for both Sharpe and Packer, more than a repeated decorative motif. Instead, figures of flora and fauna become part of present rituals as well as tributes to past peoples and recollections; they are monuments to lives of yesterday and mnemonics-in-the-making to life as it is now. To see Packer’s lush floral arrangement on the front cover of Sharpe’s book is, then, to announce the resilient beauty – as a way of thinking, acting, reflecting and seeing – noted, page after page, line upon line, within.

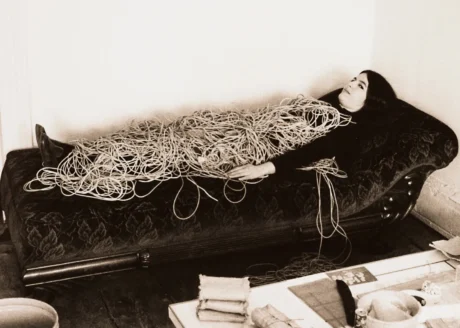

Packer initially saw her famous floral still lives as ‘palette cleansers’, a visual form of release from the heavier themes and subjects in her larger painted portraits. In time, the artist came to see the bouquets as tributes to Black men and women who were subject to anti-black police brutality, many of whom were murdered during arrest or while under police custody. Untitled was made in 2017, the same year in which Packer painted another equally poignant flower painting, Say Her Name, a work dedicated to Sandra Bland, who died in 2015 while in police custody. Though Untitled does not directly allude to BLM slogans and chants in the same way as Say Her Name, it still lays claim to the urgent politicisation and protest of the latter floral work.

One could form a never-ending daisy chain from the loaded language and suggestive symbolism that flora and fauna have accrued over time, yet a bouquet remains a culturally universal image – at once celebratory and commemorative, evoking pride and sorrow, life and death. Packer’s bouquets doubly dwell in this bitter-sweet paradox, in that her flowers are portraits for and of the dead. Made with care and feeling, conveying respect and dignity, her floral studies evoke the absent bodies, as well as the conduct they were owed by the state. In this, the artist’s slender delphiniums conveyed in spits and spurts of blue, her blousy peonies with their petals seemingly wilting off the canvas, her diminutive daisies dappling the surface in shots of white and yellow, and her lush roses languishing in their heavy-scented fragrance are all political. Powerful and rhapsodically, lyrically, poetically, beautifully, insistently political. Again, this practice and physical manifestation of care and concern in the form of flora and fauna is what Sharpe would term ‘beauty as method’.

Looking around at the recent, current and upcoming exhibitions in the UK and US, flowers appear to be the theme of the artistic season. Yet, I ask myself, to what effect are all these shows blossoming across the continents? Are they ushering in the spring? Are some of these expositions, like the returning Saatchi Gallery Blockbuster Flowers: Flora in Contemporary Art and Culture, commercially viable attempts at drawing in the flower-loving masses (especially when the RHS is but a stone’s throw away from the aforementioned gallery’s doors)? Are they ‘soft’ sells; exhibitions that neither shock nor compel socio-political commentary but offer up something pretty and palatable to passing visitors? Or are they actually highlighting something equally delicate yet profound as Packer and Sharpe’s works?

By considering several exhibitions through the ‘beauty as method’ lens of Sharpe (and Packer), what we come to see is an artistic commitment to exploring and expressing the beauty of life, however evanescent or endangered. This ‘life’ – that is, its vitality, verisimilitude, verity and vicissitudes as captured in tender buds, stems, sprigs, leaves and petals – is astutely observed and admired in the work of Sharon Core, Inka Essenhigh, Cy Twombly, Kara Walker, Jamaica Kincaid as well as Packer and Sharpe. Beauty in all its troubling and terrific significance, in its defiance against man-made threats and climate catastrophe, in its connection to the feminine and the transcendent, is shown in each work or show in full force.

Sharon Core’s recent exhibition, Facsimile at Yancey Richardson, New York, shares Packer’s desire to commemorate past lives and legacies through the floral. But where Packer’s painted floristry serves as a reminder, not a replica, of the dead before the living, Core’s subtly painted blooms are reproductions of photographer Irving Penn’s works. Taking inspiration from Penn’s book, Flowers (1980) – which itself originated from a commission published in Vogue in 1967 – Core’s paintings reinterpret photographic representation to create something materially tactile, conceptually textured, and visually true – not so much to the photographer’s hyper-exact eye, but to his artistic intentions. Like Penn’s photographs of flowers, Core’s paintings appreciate the individuality and finely crafted structure, colour and shape of flora. Unlike the photographer, who turns the elemental into the epic, Core’s close-ups of flowers create proximity and familiarity between the viewer and her work. Nature here is not a sublime botanical specimen, looming larger than its usual diminutive life and seen in glossy high definition. Rather, Core moves beyond this classificatory perspective into one of care, craft and creativity, so that her tulips, roses, poppies and peonies could almost be smelled and touched on the surface of the paper. Glistening in their lustrous colours and velvety petals, Core’s flowers appear to breathe, as well as glow, in their own painted glory.

The process which lends Core’s fleurs their luminosity is also one which complicates their veracity. Akin to Packer and artist Inka Essenhigh, whose flowers are not exactly botanically specific but pass in resemblance to actual flora and fauna, Core’s paintings are authentic but not necessarily accurate. Using UltraChrome inks on Canson Photo rag paper, she emulates Penn’s originals but does something entirely novel with the materials used to produce them. At once remixing and relinquishing the digital for the painterly, Core’s flowers appear less real, yet more vibrant and alive than their photographic counterparts. In Tulip Cottage, Tulip Sorbet (2023), which is inspired by the front cover shot of Penn’s book, deep maroon lines proliferate upwards on the outer side of the titular flower’s petals, giving us a sense of the intricate pattern and depth of colour that delights Core’s eye. In Poppy Single Oriental (2023), three stalks of the eponymous flower stand stripped of most of their translucent papery petals – but it is their seed pods, painted like round buttons or bulbous eyes, that dominate our field of vision. Core’s floral depictions give the same sense of delight one finds when looking at the botanical and natural, as well as the pleasure she takes as an artist in recreating and redrafting Penn’s photographic impressions. Accuracy and exactitude are not so important here as the felt and impressionistic reality that the flowers cast over the viewer. It is not the lens, but how we see flora and fauna that Core readdresses.

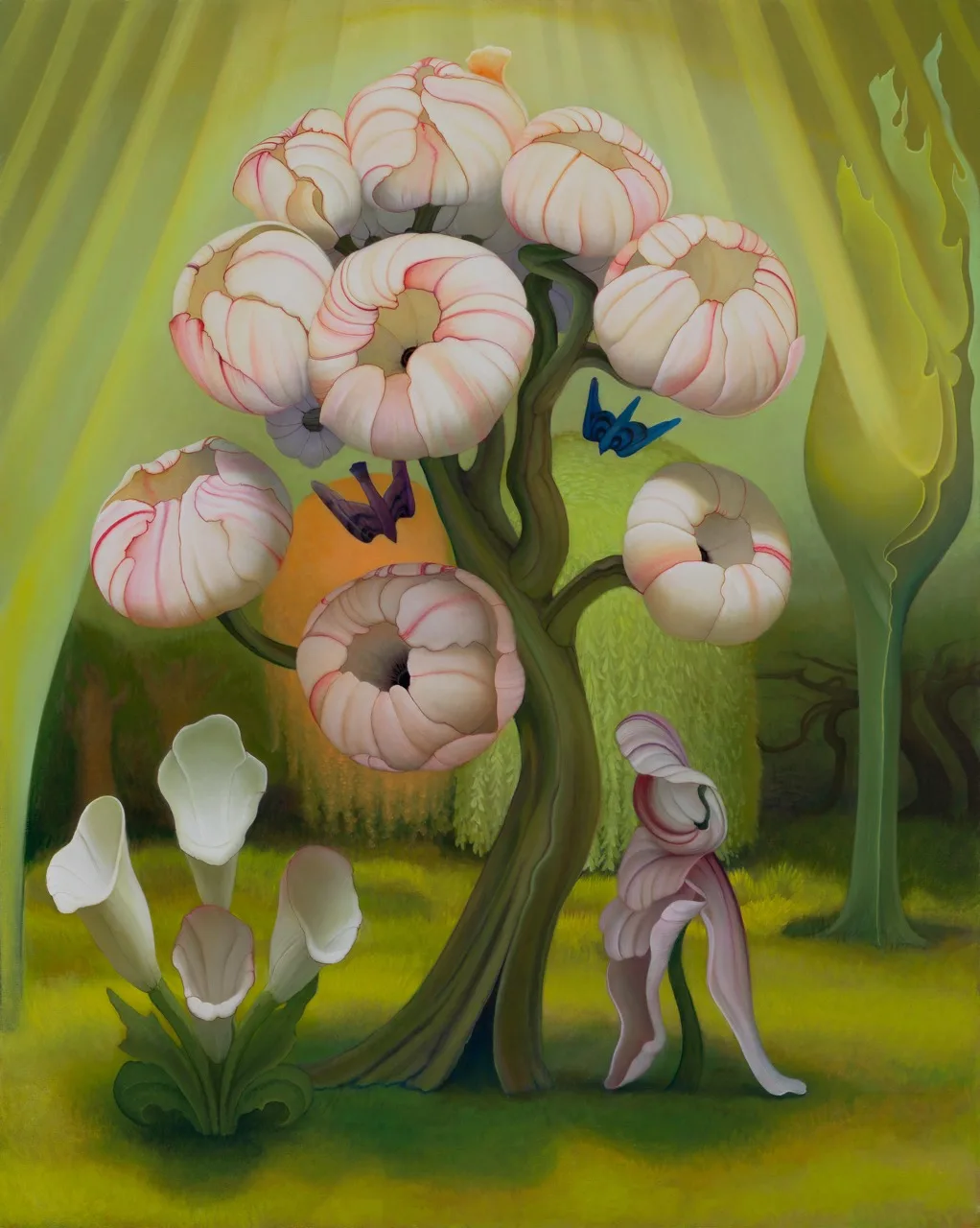

Inka Essenhigh’s recent exhibition, The Greenhouse at Victoria Miro, similarly challenges perceptions of the botanical. Like Packer and Core, she, too, forsakes strict accuracy in favour of the imagination. Talking with her over a video call, Essenhigh stresses that despite her methodology of painting (she employs a painstaking and mask-requiring method involving enamel on canvas, the final smooth surface of which is created through layers of paint) and the precision and care invested in her work, her plants and blooms are in no way botanically accurate – and neither would she have them be as such. Her haunting and somewhat fantastical figuration of flowers is positioned somewhere between the hyperreal and the surreal, with plant life assuming an almost human sentience. Botanical forms expand on the canvas, seemingly swaying and dancing in veils of light, radiating a vitality that goes beyond any photosynthetic process, exuding a consciousness not unlike our own. Essenhigh attributes this centring of the life force and largesse of flora and fauna to her desire to “be of service” artistically and to trace the unseen. Meditation, yoga, esoteric philosophies and rituals like Tarot formed a backdrop to which she reclaimed nature in her work, as well as the astute decision to step away from the depressing news cycle, which continues to consume us. But this removal only opened up a deeper awareness of the inherent life that surrounds us through nature, and a keener appreciation for the lives of these forms on the canvas. Beauty, for Essenhigh, much like it is for Sharpe and Core, is about admiring, inhaling and contemplating what’s in front of us, regardless of the socio-political storm clouds looming ahead.

Standing in front of Essenhigh’s Flowering Tree (2024), I certainly felt lulled into a meditative state. I suspect that the same slow but steadying consciousness it emits is that which Essenhigh herself has imparted into the painting. Featuring a near-anthropomorphic tree gleefully boasting peony-like pink and white blooms under shafts of diaphanous, green-tinted light, Flowering Tree plays with our sense of what plant life is and could mean – not only to us, but to the surrounding world in which it is rooted. Revelling in its spring-like plenitude and a symphony of variegated verdant shades, Flowering Tree enchants as much as it amuses. I put it to Essenhigh that through such conscious-inducing work, she is rewilding, as well as re-enchanting, our relationship to the natural. For her, though, it is more about opening ourselves up to the enchantment and wild beauty already present before us. She does not possess a purist vision of the floral and natural; if anything, her latest work, AI City (2024), reveals a surreal futurity where the natural and technological combine. In her hyper-real, hyper-conscious, hyper-surreal realisation of the floral, Essenhigh tunes into natural cycles, however slow or repetitive, and demonstrates the regeneration possible at the moment of degeneration – birth in the midst of death. Her wondrous painting, Forrest Light (2024), sees a fallen spruce sprouting candy-coloured mycelium, poppies, and a lotus-like flower almost bursting from a downpour of celestial light. Essenhigh’s point is that nature returns to itself; it finds ways to make new of old, to replenish and repair, to make noble the ancient, decaying spruce with shoots of plants and flowers yet to come.

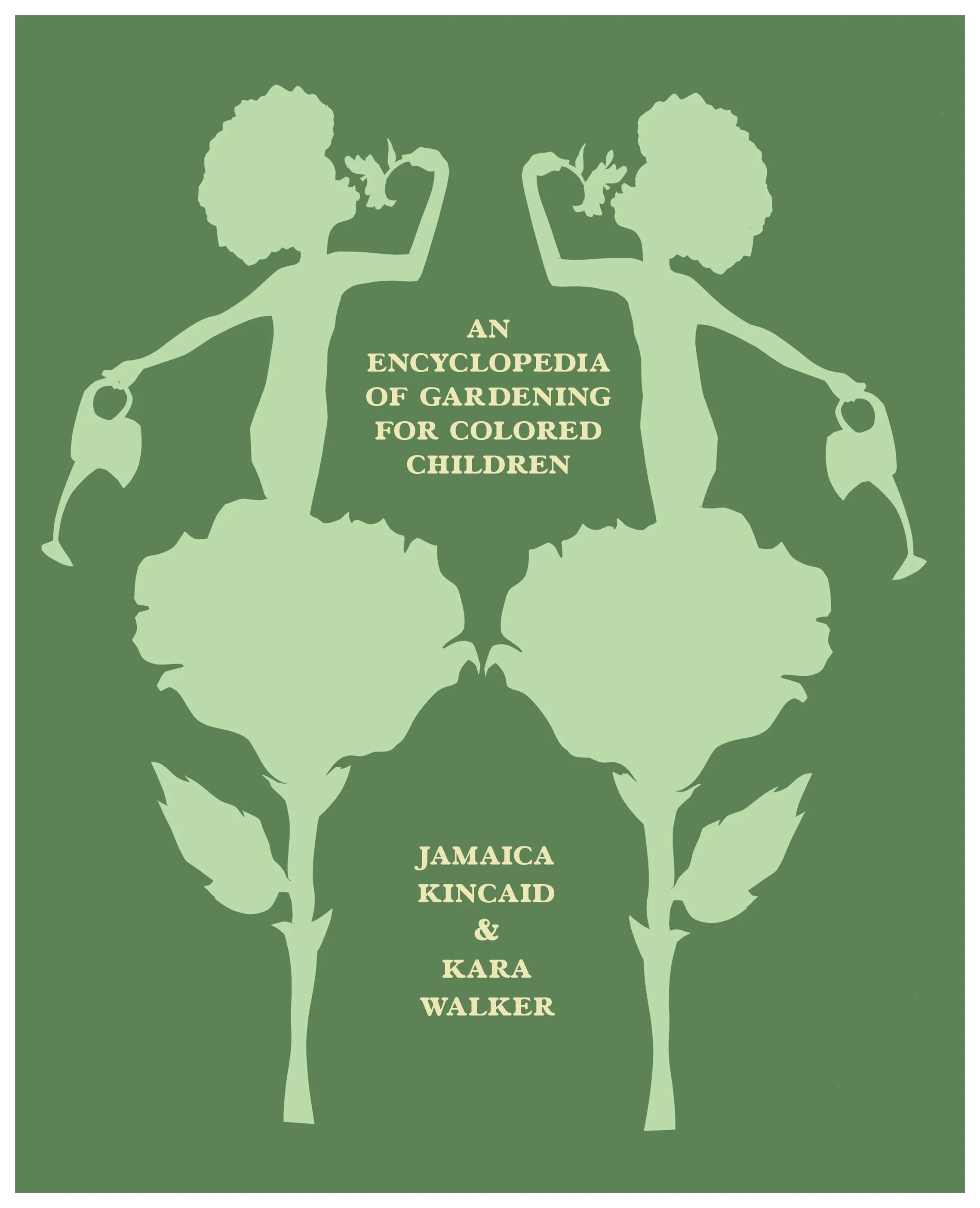

If Essenhigh invests hope in the unnoticed life of the floral, then author Jamaica Kincaid and artist Kara Walker espy in it an untold story. Much like Packer in her decolonial and antiracist positioning of bouquets, Kincaid and Walker do not so much re-appropriate floral symbolism, but reclaim and retell its origin story and place in world history. Essenhigh may situate her work within the greenhouse, that safe nursery for herbs, flowers and organic produce to flourish, but Kincaid is all about the encircling garden – a site that may also be small and controlled yet contains an atlas of the world. An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Coloured Children (2024) is a work of enlightenment (while simultaneously debunking the botanists and knowledge systems of this era); it is a book that charts with each illustrated alphabetical entry how flora and fauna are part of the histories of migration, imperialism, colonisation, slavery and globalism.

Created in collaboration with Walker, whose witty and playful watercolour and collage designs subvert what is traditionally deemed child-friendly, Kincaid’s Encyclopedia illuminates the cultural significance, literal use and historical import of plants like sunflowers, roses, hibiscus and poppies. The sunflower entry, for instance, is under its Latin nomenclature, Helianthus Annus. It outlines that despite being the national symbol of Ukraine (and an overt presence in its fields and the former nuclear site of Chernobyl), the sunflower originated in Mexico and was once worshipped by the Aztecs. Its entry into Europe came through Spanish and Russian imperial greed. Walker’s illustration initially appears innocuous, awash in a blaze of yellow as the sunflower head is decorated with a sort of (sinister?) smiley. Upon closer inspection, however, one sees a cluster of smaller sunflowers not following the sun, as the legend goes, but weeping precious seeds onto the soil. Helianthus Annus, rather than being a symbol of peace and resilience, is, for Kincaid and Walker, linked to a history of colonial rapacity, geographical displacement, ecological disturbance and cultural erasure. Yet the beauty of the garden’s flora and fauna is not forgotten, not least because of the care and craft with which both artist and writer approach this topic. Beauty is in the revelation, the careful deliberation shared with tiny readers about the realities, however harsh, that exist within the soil and flowerbeds of the garden.

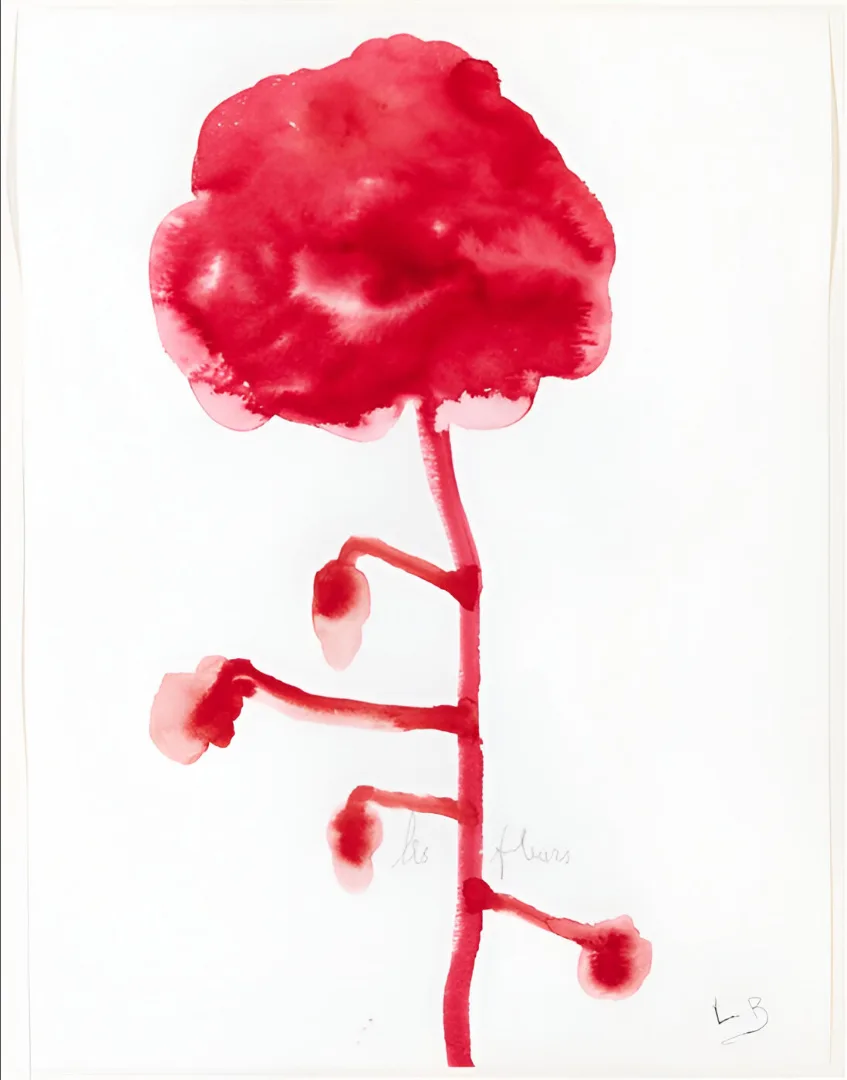

Exploding myths and symbolism around the floral is also central to The FLAG Art Foundation’s current group exhibition, A Rose Is. Walking away from the greenhouse and garden altogether, A Rose Is luxuriates in the wealth of rose-inspired paintings, sculpture, drawings and installations. Inspired by Kay Rosen’s poem of the same title (which is itself a reference to Gertrude Stein’s famous line, ‘Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose’ from Sacred Emily, 1913), A Rose Is gathers disparate representations and cultural explorations of roses throughout modern and contemporary art and literature. We move from Bourgeois’ gouache flower, diffuse and bloated on the page, to Linder’s edgy collages, where the heads of glamour models are cheekily concealed behind large peach and white roses. Both representations nod to the ubiquity of the rose whilst moving us into the subversive symbolic territory of the plant, particularly when it concerns gender and sexuality. It is the colour of the rose, though, that becomes more romanticised and exoticised than the flower itself; pink is a more daring shade to revel and revere than most would assume, considering its historical alignment with queerness as well as femininity.

Although the show more than delivers on its promise to explore the complex meanings and functions of the rose as a ‘vehicle’ for sensuality, passion, embodiment, and consumption, what is most compelling and really sings to the eye is its experimentation with colour. Generous splashes and splurges of magenta, peach and baby pink can be seen in Twombly’s series, Untitled (2003), while in Krasner’s lithograph Pink Stone (1969), bold streaks and spatters of crimson viscerally stain the paper, evoking the intoxicating scent and striking shade of the flower. Again, the beauty of colour is what captivates both artist and viewer alike, immersing both in not only the radical shades of pink and red, but in their sensory possibilities and subversive sensibilities.

Christina Sharpe’s former Twitter account formed both a timeline of protest and one of beauty. Shots of flowers – roses especially – taken on her smartphone would be tweeted amongst messages opposing fascism, fighting reproductive injustice, crying out for an end to genocide in Gaza, Congo and Sudan. But the two types of posts – botanical and political – are not necessarily distinct; the botanical, indeed the floral, can be political too. Sharpe knows this; she recognises the importance of cherishing passing moments of, and nature’s monuments to, beauty: brief sightings of a plant that blooms but once a year, or during the night, or near the kerb, or in the dust-strewn, war-torn lands of afar, rather than in an industrial greenhouse.

Flowers – the appreciation of them, the contemplation of them – can be political, but they can also simply bring joy and induce wonder. All the exhibitions and artists briefly explored above move in step with Sharpe’s sense of ‘beauty as method’; the floral can participate in these momentary bursts of delight, but it can also be part of a wider cultural, socio-political and specifically decolonial movement. Much like Packer’s bouquets, Essenhigh’s and Core’s collected flowers, and Kincaid and Walker’s collaborative garden book – all these artists and authors ask us to look again, to see the commonplace as unique, to reimagine nature and our relationship to it, to paint the world in bolder, daring colours, to see the beauty of the floral as a measure and mode to live by, not just with. Cherishing her mother’s small acts of beauty – the lists of books she made, the little garden she tended to, the flowery embroidery she had sewn on her girlhood dress – and the repeated forms of attention and care which made up her life, Sharpe asks us to look again, and in looking, cherish all that’s beautiful in the world anew.

Written by Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou

- Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe is published by Daunt Books and is available to purchase online and in all good bookshops now.

- An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Coloured Children by Jamaica Kincaid, featuring illustrations by Kara Walker, is published by Giroux and Strauss and is available to purchase online and in all good bookshops now.

- A Rose Is continues at the FLAG Art Foundation, New York, until 21 June 2025. For more information, see here.