“Light and shadow are my thing,” said American experimental filmmaker Sara Driver, whose interests range from expressionism to fairytales and horror B-movies. Her films have been described as “doorways into the unknown”. It seems characteristic that her celebrated first film,

You Are Not I (1981; an adaptation of a story by Paul Bowles), was long believed lost after a warehouse fire destroyed the negative, until a copy was found among the effects of Paul Bowles after his death. Her new film, documentary Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat, revisits Lower Manhattan in the 1970s.

Can you talk me through the genesis of Boom for Real? How did it all come together?

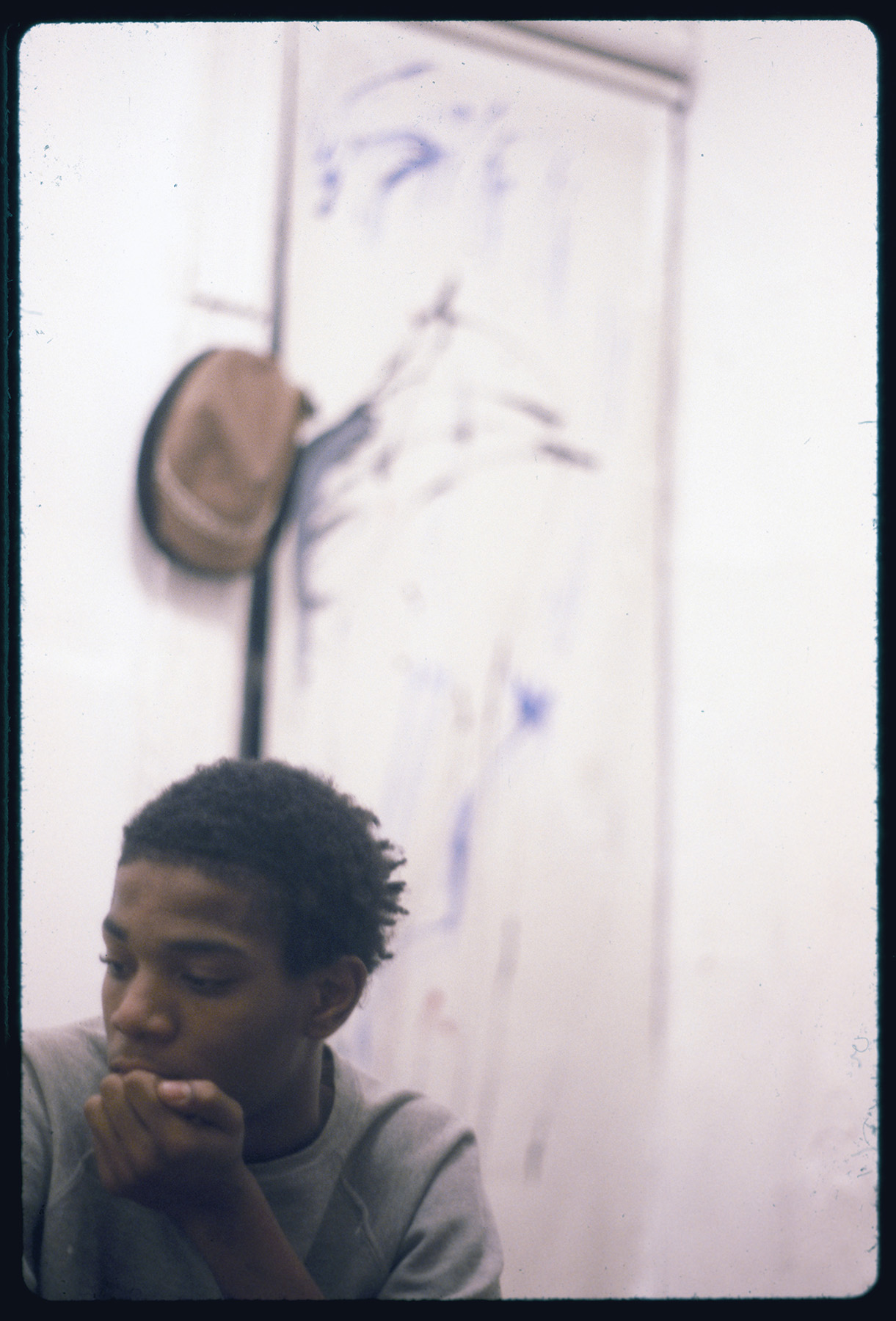

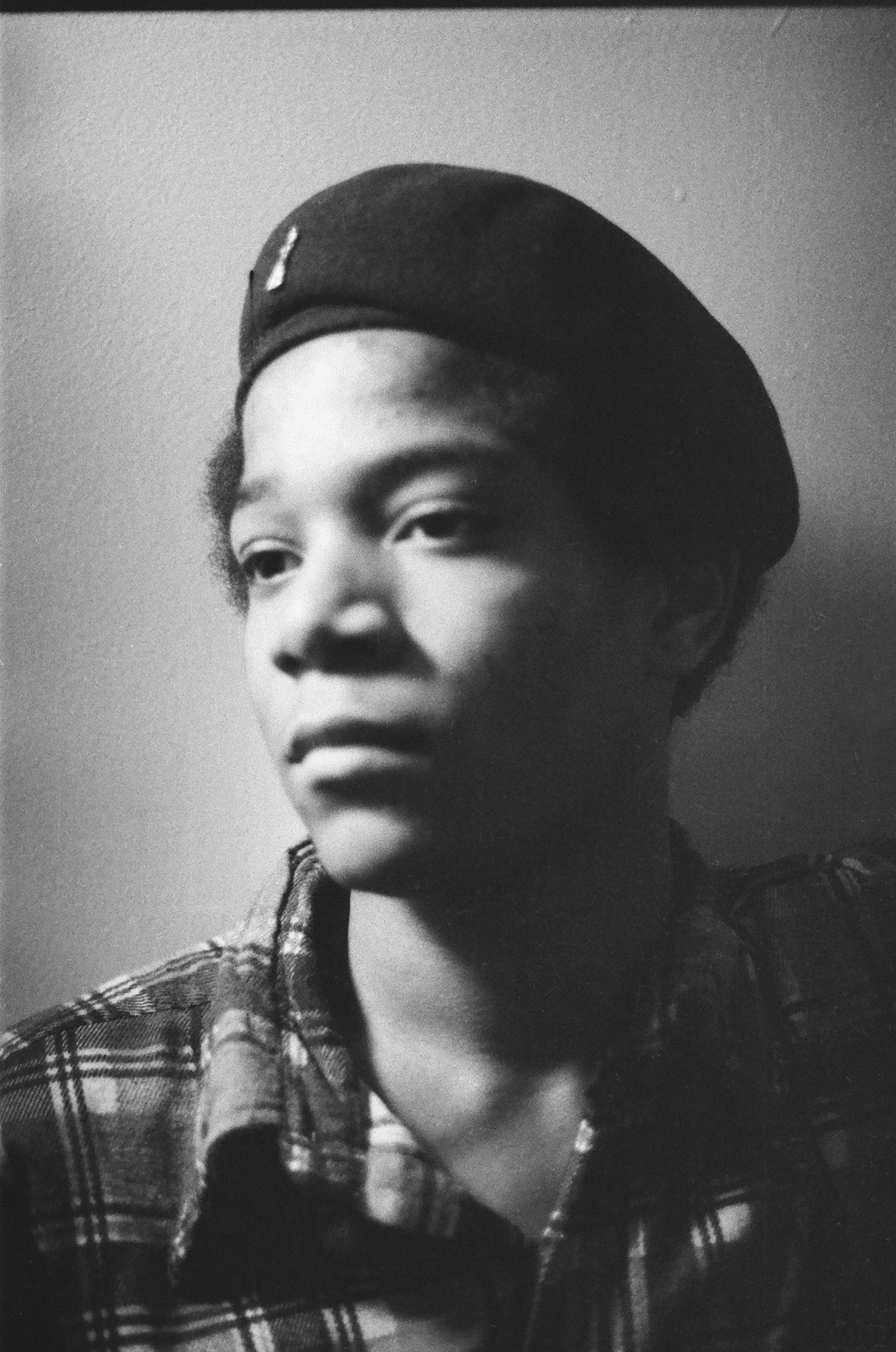

We had a disastrous hurricane in 2012: Sandy. My friend Alexis Adler, an embryologist, had lived with Jean-Michel from 1979 to 1980 on the top floor of a tenement; she’s still living in the same apartment. She had a mural by him on her wall and a bathroom door that was painted by him, and when Sandy hit, she started getting very worried about them because they were starting to pucker and stuff. And then she also had forgotten that she had put away all this work that he had left at her house thirty years before. It was underground in a bank vault, so she was very afraid that it had been flooded. She went and opened it up and there were sixty works that she’d forgotten about; writings, notebooks. And then she remembered that she had this box put away of clothing that he had painted. Alexis is a really, really free person. Most people were throwing him out of the house when he started painting on their walls, but she was encouraging him. She let him paint on the floors, and I told her it must have been like living with an elf: you wake up the next day and your shoes are made, and there’s a new painting! And then she had taken like 150 really wonderful photographs because she’s also a photographer.

I was one of the first people to see what she had, and I just thought this is a window not only into him but also into New York at that time. I was given an opportunity to make a film about the beginnings of a young artist. The witnesses are still living, so that’s pretty rare. There were so few works of his from that period because he was so transient, and it was such a specific moment in time in New York history, the zeitgeist of people coming together.

“Because we had such a punk attitude and no fear of failure because we had nothing to lose, we were trying everything, failing and succeeding on a small level”

You too were there at the time, part of the same creative scene. What was Jean-Michel Basquiat like?

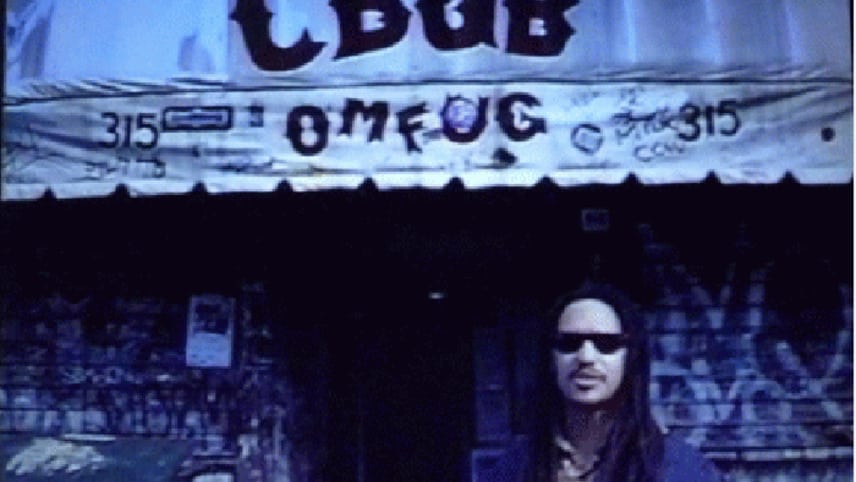

He was like this kid. I met him properly when I was about twenty-two and he was eighteen or something. And then we all knew that he was SAMO [Basquiat’s graffiti art moniker, which he shared with fellow artist Al Diaz]. Like all of us, everybody was just on the streets, so we all knew each other.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in New Jersey. My dad commuted to the city and so I grew up with the shadow of the city always over me. My older sister worked at Max’s Kansas City, and I knew I was gonna live in New York City! I knew about the Factory and I was always drawn to what Warhol was doing, like so many of us. It’s a long love affair with New York.

From the film you get a sense of the dereliction of deserted New York in the late 1970s, but at the same time, for those creative people who did live there it was intimate: everyone knew everyone else. New York is no longer like that, is it?

I think the nature of the modern world has been to departmentalize different mediums. Whereas for filmmakers, for example, you have to know art history, you have to know dance to think about the movement of a camera, all these things feed each other. Because we had such a punk attitude and no fear of failure because we had nothing to lose, we were trying everything, failing and succeeding on a small level. That’s something that I feel is important to express to kids today: just pick up a guitar even if you’re not musical, just try things. I think today there’s enormous stress on them to do everything right and that’s not how you learn. You also learn through other people, so it’s very important to have that contact and exchange of ideas, which I think social media has tampered.

What about the choice of the particular period of Basquiat’s life you cover in the film?

The story of his later years has been told. This was a story that interested me because it’s about an artist in their very formative years. He was a very advanced poet when he was eighteen years old. He would make very deliberate sentences and cross things out just like he does in his paintings, on these pieces of notebook paper. It’s a great gift that we have Alexis’s collection to be able to really archaeologically look at what the ideas were he was playing with. He’s not known for many sculptures, for example, but she’s photographed the ones he was making from stuff he dragged up from the street.

Is one of the remarkable things about Basquiat that his creativity was so transferable? He was a writer, a sculptor, a painter, a musician, a performer…

I think he picked his own university. He was going to Jim (Jarmusch, the film director) or to (graffiti artist) Lee Quinones and learning from them. Lee is such an accomplished painter. I think it’s so funny in the film where he says: “And Jean would let his paintings drip. I would never let my paintings drip!” And then you see him sitting, there’s a painting behind him and it’s all drippy. Lee is such a major cultural figure who I hope gets the recognition that he deserves. He painted over a hundred trains between the ages of thirteen and fifteen. He told me that he used to paint the inside of his mother’s kitchen cabinets with what he was going to do on a train that night. Then he’d go up there by himself. So I learned a lot too doing the film.

“And Jean would let his paintings drip. I would never let my paintings drip!”

How does film fit for you within your own oeuvre?

Well, I love ghost stories: I love them in books, I love them in movies. When Pigs Fly, the last film I made, was a ghost story, and with Boom for Real, I remember saying to the editor: “Just make Jean a ghost through the film.” And there’s no audio at that time, or very little, so…

What is your next project?

I have about five! I love folk tales of the metamorphosis of human to animal and animal to human, so I picked seven stories from all over the world and I’ve written seven short scripts for children. I’m very interested in in-camera effects and dealing with light and shadow, instead of those very computerized effects, and children are very interested in how to do those. I also like the idea of the “exquisite corpse”, where you take an idea and you throw it at somebody else and you see what they do with it, so I’d like to throw it at a few different directors, the premise being the only thing they have to do is it has to be made for children, and all the effects have to be done in camera, with light and shadow.

And it’s been a kind of interesting challenge too to think of who are the living imagination directors, who are the directors who have childlike minds that would really dance with this: Michel Gondry, Marjane Satrapi and Deepa Mehta have all agreed that they’d like to do one if I get the financing. That’s a big project and passion for me. I have another project about humans that are bees, these very perky girls that are on their way to college, but they start killing off each other and you realise that one of them is the queen bee. And that’s my love of Hammer Horror films too.