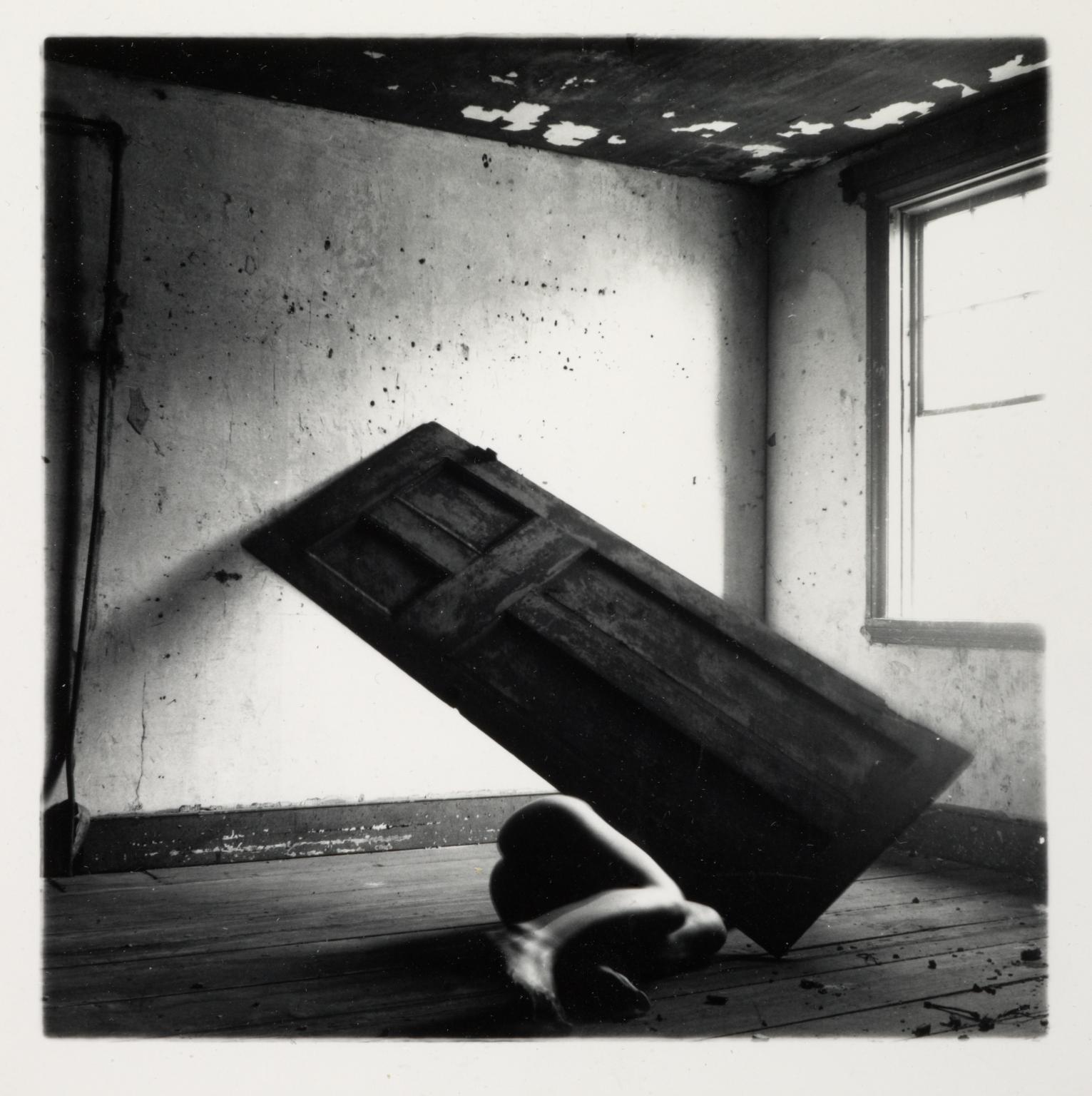

A figure looks like she might be about to fall in the black-and-white self-portrait, titled Space², Providence, Rhode Island (1976). Perhaps she stumbles, her blurred face an indistinguishable smudge, making it difficult to know what story it might tell us. One might assume that someone off-camera has pushed her; she grasps outward, trying to steady herself. The artist is Francesca Woodman. Her figure disappears into the unsteady domesticity of the home that surrounds her. Her vulnerable stance seems to gesture towards the unseen terror of our interior lives: the quiet, subtle violences that undo us. What happens when we are no longer recognisable to ourselves? What undoes us such that we want to vanish without a trace?

What does it mean, then, to be both made and broken by others? Judith Butler once argued, “Let’s face it. We’re undone by each other.” We are, according to Butler, vulnerable just by trying to live; our bodies are always entangled in complex systems of care and support, and this undoing is what opens us onto—or asks us to face—something else more imagined and collective, something that is beyond individuation. Something that might, in numerous ways, feel violent or uncomfortable, or pleasurable, or wonderful.

“How can ideological systems, with very material effects, punch and break the surface of a body?”

Sayaka Murata’s latest novel Earthlings (2018, translated 2020) explores how our bodies are routinely and operationally clawed from us, and what happens when we no longer feel like they belong to us. Murata asks us to consider how we survive when violence, trauma, heterosexuality and capitalism have simultaneously wrought themselves upon a body, emptying and cauterising it of anything that might have once animated it. How can ideological systems, with very material effects, punch and break the surface of a body and embed themselves beneath the membranes of the skin like parasites? What happens when that which you cannot control—the small quiet violences of the world—make life impossible, and you are left simply to survive? And what would it mean to feel alienated from the intimacy we are told we must seek at all costs?

The narrator, Natsuki Sasamoto, is born into a family that does not love her and who show little-to-no affection or warmth, instead chastising, taunting and bullying her. What ensues is a story about incest, paedophilia, abuse, trauma and intimacy, all portrayed in Murata’s trademark sparse, affectless prose—a tonal cadence recognisable from Convenience Store Woman (2016, translated 2018). If feminist critic Sianne Ngai argues that animated-ness, or “being moved” is often associated with the “overemotional”’ racialised subject, Murata’s prose style belies any semblance of this. Natsuki is withdrawn, expressionless and refuses to emote outwardly, despite the violence enacted against her. Instead, she projects her energy into a fantasy world, believing she is an alien from planet Popinpobopia.

The only thing Natsuki looks forward to is the annual visit to Akishina in the wild Nagano mountains, where her family gather to celebrate the holidays and where she spends time with her cousin, Yuu. Estranged from their families, Yuu and Natsuki, encouraged by Natsuki’s cuddly toy hedgehog, Piyyut, exist in their shared fantasy world. To bind them together further, the pair create a marriage pledge, where they promise one another “to survive whatever it takes”.

“Natsuki is withdrawn, expressionless and refuses to emote outwardly, despite the violence enacted against her”

Returning from the summer trip, Natsuki attends cram school where she is raped. Entering further into a dissociative space, she retreats into the world of Popinpobopia and the safety of alien life that this world and Yuu promise. What follows is the traumatic aftermath of sexual assault; reeling in shame and the belief that perhaps she made all of this up (her mother chastises her for accusing her teacher), Natsuki constantly wills herself into disappearance, to the point that when her grandfather dies, she considers dying right there and then so that the adults don’t need to dig another hole.

If Earthlings are heterosexual, sexual beings, to be an alien is to resist heteronormativity and the tyranny of the couple form. As Natsuki progresses into adulthood, she finds herself even further alienated from intimate life. Registering on “surinuke.com” at the age of 31, Natsuki finds a man who doesn’t want sex or children, simply a registered marriage: it is nothing more, really, than a glorified flatshare. Marriage here is a linchpin for debates about morality, kinship, belonging and citizenship.

Murata reveals the pressure behind leading intimate lives, and how some intimate worlds are watched and regulated far more than others. Crudely put, the novel warns of the reproductive pressures and heteronormativity of society; if dystopian literature imagines spaces of great pain and injustice, “the baby factory” where Natsuki lives is a very real world—where there are mounting expectations to settle down, procreate and live in harmonious sexual union with your partner.

Like with most dystopian literature, I can get on board with a concept taken to its logical extreme, and the glowering refrain of this novel is that alienation from the body is a foundational trait of the labour-relation under capital. In Murata’s world, those who submit themselves to procreation, reproduction and marriage are dubbed the eponymous Earthlings, whereas those, like Natsuki and her husband Tomoya, who try to eschew these reproductive responsibilities are aliens.

“The novel’s refrain is that alienation from the body is a foundational trait of the labour-relation under capital”

Fundamentally, Natsuki doesn’t want to become “a tool for the baby factory”, despite feeling the eyes of the factory at all times. Her family watches her, and she experiences anxiety at the constant pressure to make her marriage stand up to the contract she signed, including becoming an efficient worker, maintaining a home, pregnancy and child-rearing. In essence, Natsuki is cognisant of how, as Silvia Federici might articulate it, the distribution of reproductive capacity subsumes social relations under capitalism. Natsuki fantasises about a faraway world far away where she doesn’t need to “assimilate” to “factory standards”.

For Natsuki and her husband, it is also pleasure and sexual intimacy that are unfamiliar. Yet not even Earthlings really seem to know what real intimacy might or could look like. Even Natsuki’s sister, the cruel and taunting Kise, exposes the performativity of intimacy towards the end of the novel. Indeed, in bearing witness to Natsuki’s marriage, where there is “no sexual contact” and they share neither meals nor a bed, Murata seems to expose the innate difficulties of intimate attachment, especially for those who see no option other than to enter into a farce for fear of societal punishment.

Yet in Natsuki and Tomoya’s performance of their marriage, Murata reveals the inescapability of heterosexuality and the overt challenges of intimate attachments (especially as it is tied to investments in the state, society, family: “the factory”, “the baby factory” etc). And while alternative intimacies might attempt to leak outside of the regulatory union of heterosexual marriage—take Natsuki and Tomoya’s trip to Akishina—they remain necessarily bound through a performative contract at all times.

For Natsuki then, the binds of social relations feel like a trap; she is cruelly undone by those around her: exploited, shamed, abused, unloved, useless and made helpless and precarious. The artist Jesse Darling’s practice explores this fissure between violence and care: the stakes of the spectacular vulnerability of social relations and interconnectedness to other bodies, inherited ideologies and to the worlds we build. For example, Spirit Level (2015), Darling’s second show of work made with the artist Takeshi Shiomitsu, presents suspended milk cartons, pink punching bags with looped chains attached, mint-green tourniquet and broken plastic. These chosen materials—at once punctured, wounded, pounded, collapsed—signal a persistent reminder of the off-stage violence enacted upon gendered and racialised bodies, whether biopolitical, physical or psychic. They create the sense that this vulnerability could open you up and splinter your hardness.

As readers, we are left wondering whether Planet Popinpobopia might realise this sort of utopian thought, a communal place where there is no pressure to make your body productive or consent to sexual encounters you don’t wish to enter into. The other side of being undone is that bodies—some far more than others—are also uniquely vulnerable to the violences of the world. Much like Piyyut throughout Earthlings, I wanted to protect Natsuki. I found myself wincing at the pages—how I sometimes feel when looking at Woodman’s photographs, like I want to stop her from falling. I wanted to scoop her up and out from the world she inhabits and offer her safety. We undo one another in both terrible and inimitable ways.

Come As Softly is a book column by Bryony White on intimacy, desire and sex.