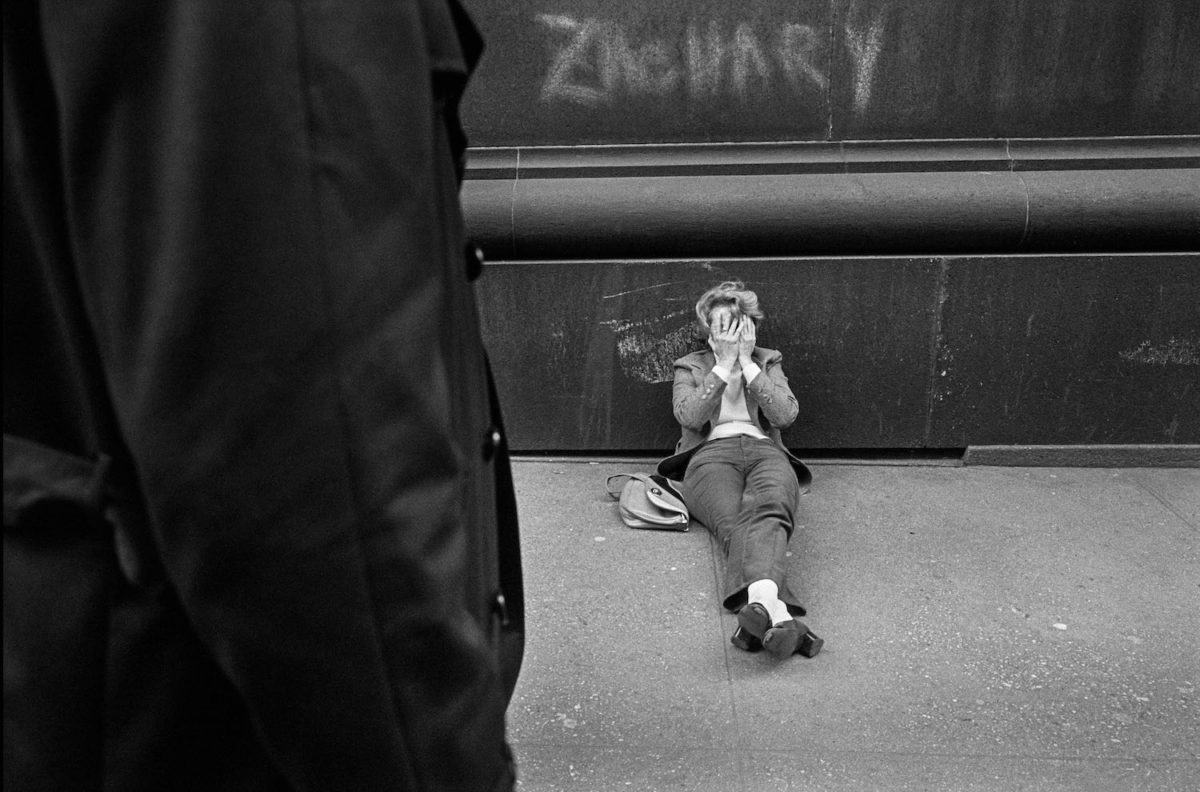

USA, NYC, 1978, from Lost and Found

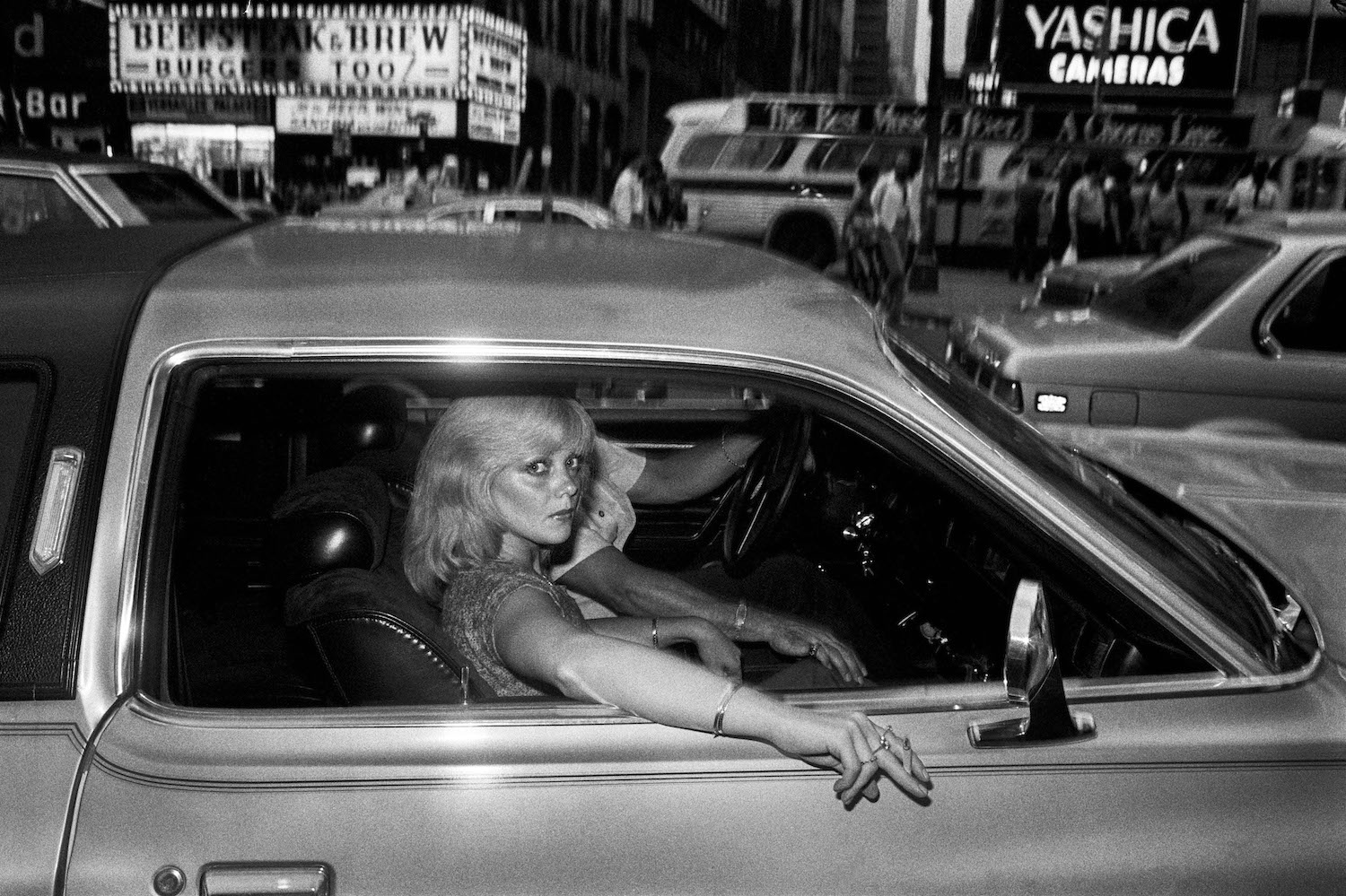

As an Englishwoman very much not at home in New York, you can almost hear the “Ahm waaawkin’ here!”, the “cawfee!”, the screeching of big yellow taxis, a Lou Reed-esque drawl and muttering in these stunning images from Bruce Gilden. The street photographer best known for his use of bright flashbulbs and unflinching (or, you could say, unflattering) portraiture, showcases his earlier black and white images of the city in a new book of his early work. The expansive monograph, Lost and Found, published by Artbook/Éditions Xavier Barral, documents the enormously characterful folk of everyday NYC, in a city so vastly different from our present-day reality as to appear even older than their late seventies and early eighties date stamps testify.

The book is the product of Gilden moving out of the house he has lived in for the past thirty-five years: in the process, he discovered cardboard boxes containing hundreds of contact prints and negatives of images shot in his native New York—many of which are not just new to the public, but new to (or at least forgotten by) their creator himself.

- Left: USA, NYC, 1980. Right: USA, NYC, 1982. Both from Lost and Found

“You feel the dirt, you feel the sweat, you feel the sleaziness, you feel the tension, you feel… New York”

“I spent practically the whole summer of 2018 looking through more than two thousand rolls,” he says. “It was an anthropologist’s job and when I discovered these images, I was very surprised because I didn’t think that I had anything on these rolls… what was interesting about the whole story is that it felt like I had created a whole new body of work, and if I had died this work would never have seen the light of day.” Gilden selected around 100 images from this vast collection; each of these offers a raw, brilliant portrait of the city he loves for all its then-griminess and strangeness, and the people that made it so.

Gilden has previously billed his New York work as “my lifetime project”, and these images show why: the city and its inhabitants are unendingly fascinating, especially when caught through the careful, wry and fortuitous eyes of this artist. Gilden states in the book that, to him, what defines street photography is “when you can smell the street and feel the dirt, and that’s what you feel in these pictures. You feel the dirt, you feel the sweat, you feel the sleaziness, you feel the tension, you feel… New York. I captured what was there and it was a tough time. It was raw, violent, and filthy but it had lots of soul. My kind of town!”

Born in Brooklyn, Gilden has over the past decades made a name for himself as a street photographer shooting all over the world; from Haiti to France, Ireland, India, Russia, Japan, England and, of course, America. These images showcase a time when Gilden was an emerging photographer in his thirties—he was still a taxi driver, and remained so for four years—and a New York very different to that of today. The late 1970s were described by the New York Times as “some of the darkest, bleakest years” in its history, and as “…

edgy and dangerous, when women carried mace spray in their purses, when even men asked the taxi driver to wait until they’d crossed the fifteen feet to the front door of their building, when a blackout plunged whole neighbourhoods into frantic looting.”

As such, Gilden’s images—along with their undeniable charm—carry a feeling of tension, rather than nostalgia. They provide a snapshot of a city that was brimming with both creativity and a lurking sense of danger. They also carry a certain imperfection, according to Gilden, since they were shot so early in his career: “But they work well across the frame. Sometimes it doesn’t help when a photograph looks too perfect. My photographs don’t look staged, you can spot a head or an arm askew here and there, and I like that: it looks like I just came upon it in the street—which is what happened. I like surprises even if I am a perfectionist, because if a picture is flawless, it looks too structured.”

- Left: USA, NYC, 1981. Right: USA, NYC, 1979. Both from Lost and Found

“It felt like I had created a whole new body of work, and if I had died this work would never have seen the light of day”

Each image is incredibly energetic, a testament to both this city and era, and Gilden’s knack for finding that elusive Cartier-Bresson “decisive moment”. And while his portraits are entirely off-the-cuff, and often portray people looking less-than-happy about being snapped, there’s an affection to them, too. “I like a bit of filth and I don’t call people scum,” says Gilden in the book. “The type of people that interest me visually may not be your average people but it doesn’t mean I’m prejudiced about them.”

- Left: NYC, Brighton Beach, 1978. Right: USA, NYC, 1986. Both from Lost and Found