Artist Isaiah Davis speaks with Nicole Eisenman about her latest exhibition in Paris, as well as how her new works speak to her corpus as a whole. They talk about artistic practices, sexy cubism, and what animal they’d like to be.

There are many subtle tensions in Nicole Eisenman’s ominous, humorous world. Absurdity and sensuality. Romance and abjection. And now, in her latest exhibition, WITH, AND, OF, ON, SCULPTURE, on view at Hauser & Wirth in Paris until September 21, it’s sculpture and painting that emerge as the main counterparts in a dialogue punctuated by both monumental figures and plastic to-go cup lids. Nicole Eisenman has had a serious sculptural practice for 12 years and yet, “I still think of myself as a painter who makes sculpture,” she confesses. Anointing the show with a winking nod to self-conscious relationality (with, and, of, on), Eisenman organizes the exhibition around a negotiation of the exchange between her respective practices. At the same time, she has her first major retrospective currently on view at MCA Chicago titled What Happened?, the majority of which is figurative painting produced from 1992 to today.

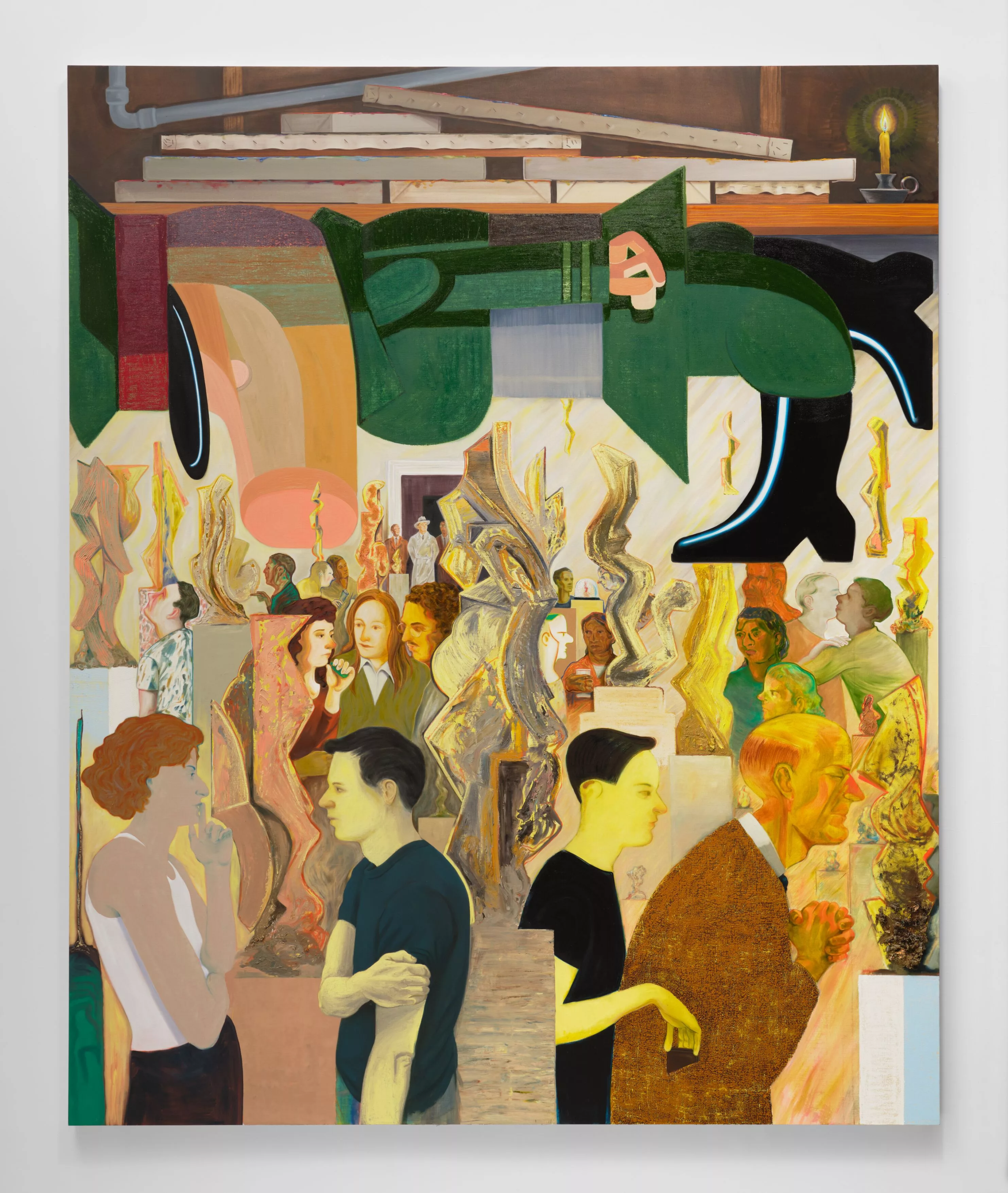

Artist Isaiah Davis met up with Eisenman at her studio in Williamsburg to chat. They discussed some favorite new works from the Paris show— including Archangel (The Visitors), a painting portraying a gallery opening with a looming reference to John Heartfield and Rudolph Schlichter’s post-WWI fascist pig Prussian Archangel, and Mad Cat, a bronze bust of an anthropomorphized feline sporting a helmet fashioned from a broken mid-century chair (both 2024). Teasing out the implications of Eisenman’s show, the two sculptors consider the political state of the world, the power of objecthood, and humor as a Trojan horse.

Isaiah Davis: Okay! So why did you title your show WITH, AND, OF, ON SCULPTURE?

Nicole Eisenman: The title refers to the various ways the 2-D work in the show relates to sculpture. I started doing 3-D work in 2012, so even though I’ve been at it for 12 years already, I still think of myself as a painter who makes sculpture. I often get asked how moving into sculpture has affected my painting, one of the aims of this show is to answer that question.

ID: Have you always been influenced by sculpture in your paintings?

NE: There are a number of paintings in this show that I approached in similar ways to how I might build a sculpture, it’s a process of building and carving out blocks of shapes. With painting, you have to convince someone of a reality that doesn’t exist. Whereas sculpture, in its three dimensionality, simply is. Painting is a head trip.

ID: Do you feel like that illusionistic trickery takes place in sculpture?

NE: For me, sculpture is very matter of fact. What you see is what you get. Like if you were to take an anvil, hang it from the ceiling and walk underneath it, you’re gonna feel like you can be killed by it. Whereas with a painting, you’re going to have to do a lot of work to create that feeling of weight and it will always remain an idea.

ID: When I look at sculpture I’m constantly looking for potential trickery. Like welding a hollow box form of steel versus casting a box form of solid steel, for example. Even though both of them are representational of a solid, visually you know that one is hollow and the other one isn’t, but to get to the point where the hollow form reads as solid requires a lot of zhuzhing.

NE: Totally! I think of Charles Ray as a sculptor who likes to get tricky with material.

ID: I read that for you, painting is from the neck up and sculpture is from the neck down.

NE: I mean that painting feels like a very cognitive process… abstraction or figurations, it’s illusionistic to some degree, right? Three-dimensional work, you can touch it, it’s more of the body, you can read texture with your eyes and with your hands. I don’t know about you, but I almost always touch sculpture in museums and galleries. I want to feel what it’s made out of.

ID: Absolutely. As a sculptor there is a part of me that wants to touch the work, but I know I shouldn’t.

NE: I’ll sneak behind sculptures and knock on them. What I like about doing outdoor sculpture is that kids can climb on them, people sit and lean on them.

ID: Outdoor sculpture has a ruggedness to it.

NE: They’re built to take it.

ID: I feel like this show of yours levels the playing field for both your painting and sculpture.

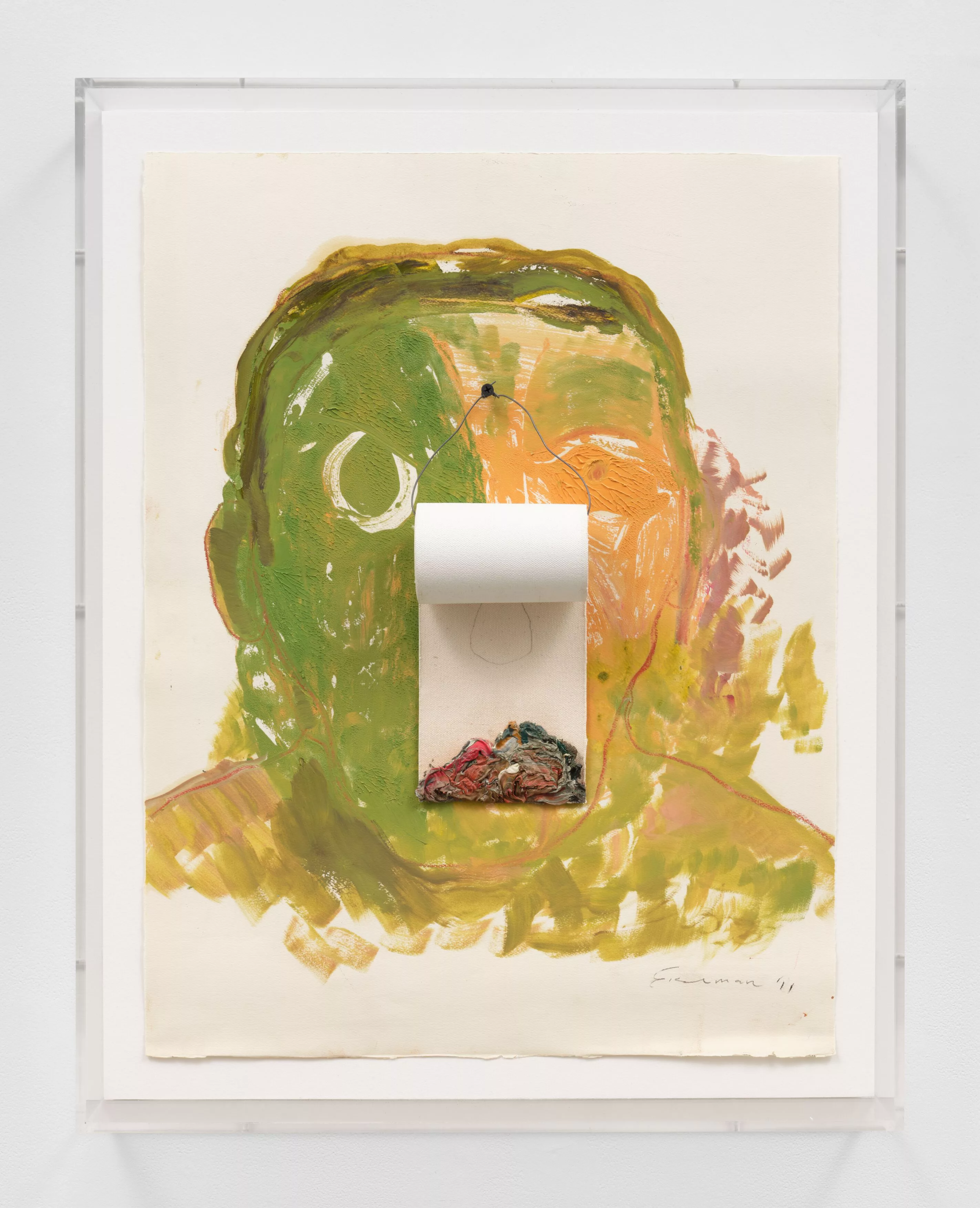

NE: The show is a mix of painting’s which are what I call constructed heads—the paintings which have a built quality—plus two-dimensional work from my sculpture studio and also some new sculptures. I have a separate studio where I make sculpture but sometimes two-dimensional stuff comes out of there, like either preparatory drawings for sculptures or byproducts of sculptures. For instance you have a bunch of extra material and you pour it on a piece of paper to begin a drawing or use sheets of plywood as a ground for drawing and use wax or cutting tools to make lines, this kind of thing.

ID: The Visitors painting. My friend described it as the keystone to the entire show.

NE: Yes, sure, a keystone.

ID: It holds it altogether with this kind of ominous glue.

NE: The scene in the painting takes place in a sculpture show with a big pig-like form, hanging over it.

ID: The painting has an obvious reference to Prussian Archangel. It’s a heavy gesture. Honestly it scares me.

NE: It’s so big and no one is paying attention to it in the painting.

ID: I feel like looking at that painting presents a potential truth. I’m more fearful of looking back at that painting in the future than how it feels looking at it now.

NE: Humans are having a hard time changing course.

ID: It reminds me of the feeling I had looking at one of your earlier works. Specifically Morning Studio. When I first saw it, it reminded me of my first real romantic relationship.

NE: That’s unexpected!

ID: It was sweet and intimate and felt like a window into my first relationship but in a very private way. I bring it up because the intimacy of the painting felt so real that it displaces the timeline in my memory. The immediate nostalgia I felt when I first saw that painting took me to the time when I felt like that painting took place.

NE: Time travel is real.

ID: Yeah, and with The Visitor I feel like you made this window into a foreboding future.

NE: It feels like we know where we’re headed at this moment, not caring if we super heat the globe or commit genocide.

ID: Yeah it’s a crazy thing.

NE: The thing about Prussian Archangel: it was made in 1920 as a response to the devastation of World War 1. It’s this horrible pig mannequin wearing a soldier’s uniform. I’ve been thinking about that sculpture for such a long time now, like 30 years. It’s heavy and ugly and militaristic.

ID: But something about that sculpture that’s interesting. The impetus behind the birth of Archangel was for press and circulation. It’s an early example of virality.

NE: That’s cool, it definitely worked—I’m still thinking about it 104 years later!

ID: I’ve been thinking a lot about contemporary sculpture recently, and flirting with this concept of frictionless sculpture.

NE: What do you mean by frictionless?

ID: Complacent works that circulate within the art world and market suspiciously well. Like the system itself dictates its form.

NE: Work made for the marketplace—sounds cynical. And that’s obviously not limited to sculpture.

ID: Absolutely.

NE: I like the idea of art as a kind of proposal.

ID: It needs faith or optimism.

NE: Frictionless art sounds pessimistic but also I’d never blame an artist for pandering to the market or cashing in on their jam. It’s such a reasonable path given the world we live in. At the same time, nah.

ID: Right, it’s too bleak. It’s not a holistic view of the world we live in.

NE: I think optimism is a great word to bring into the conversation because even if we’re fearful or bewildered by the future, there is an optimistic feeling in making art, it’s a generative act of love and curiosity.

ID: I think so, too. It’s like, what else am I doing this for?

NE: I like playing around with shapes and constructing abstracted figures but I also want to show things as they are.

ID: What do you mean by show things as they are?

NE: There’s a kind of savagery in our culture that’s really hard to look at. For example how the U.S. supports this brutal and devastating genocide in Gaza.

ID: It’s really, really bad. It’s rampant savagery.

NE: It’s gutting and depressing and infuriating. Yet we have to keep living, we have to be creative in the face of violence and utterly sterilizing lack of imagination.

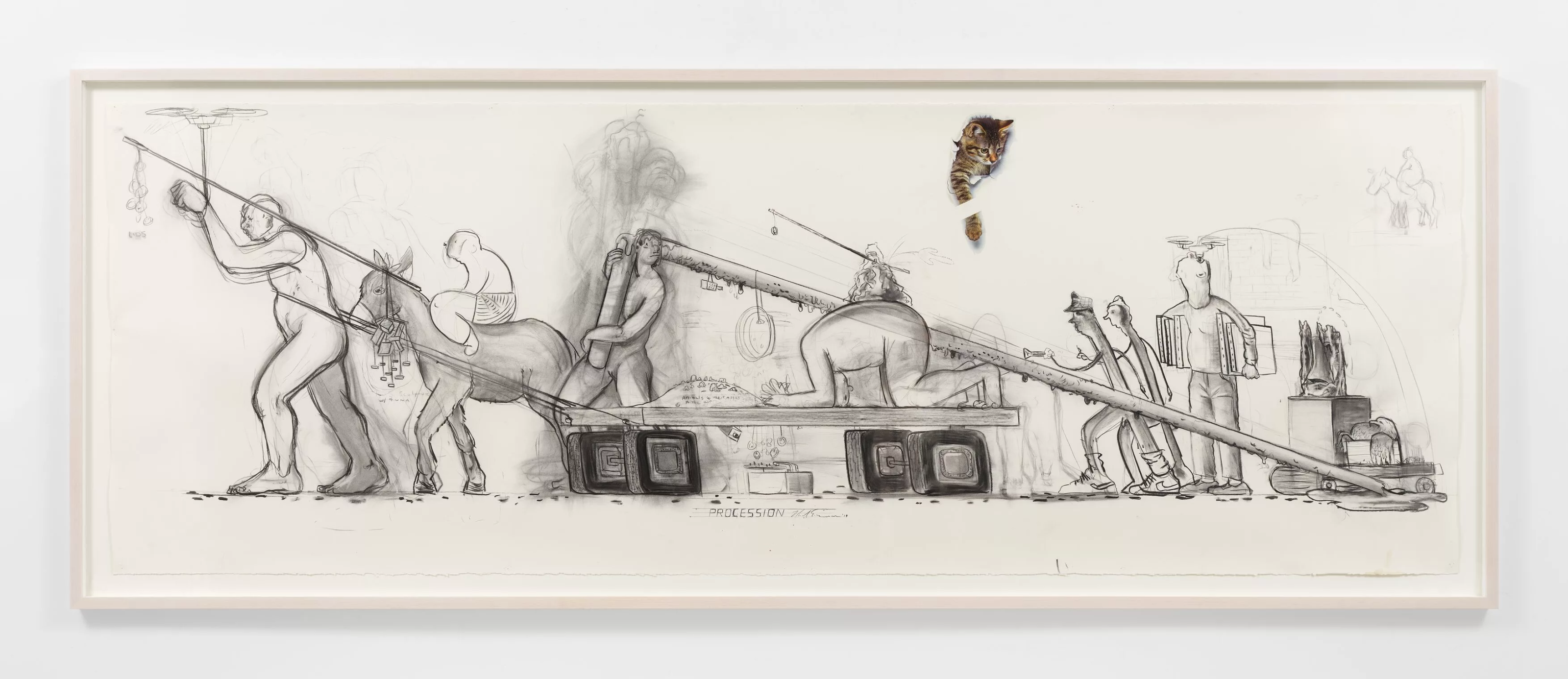

ID: Absolutely. How do we keep creating? With Perpetual Motion Machine, I think about the modularity of it—how it can be recomposed in different ways, but still be entirely new works with their own identity. In some ways similar to some of Terry Adkins sculptures. I read that your sculptural work has been motivated in part by the question of how to tie groups of figures together— in a sense, to write a story and use sculpture to tell it. Like the theater. And in theater, you have this non-consequential object genre of the prop.

NE: A non consequential what?!

ID: A non-consequential object, like its power is only on the stage. But in an art context, the prop can be a Trojan horse, because the effect of the object is activated through viewer interaction.

NE: You’re thinking about my sculptures as props?

ID: Yeah, sorta. You have this language of theater in some of your sculptural compositions. And when you take into account, your relationship to sculpture and painting the whole space becomes a kind of theater.

NE: That’s a cool idea. I remember theatricality having bad connotations from my schooling at RISD. Drama was pooh-poohed which, now that I think of it, is so homophobic! I did think about that sculpture The Procession that was in the Whitney Biennial in 2019 as a piece that could be added to indefinitely. I called it the kitchen sink of sculptures! The only limit to the piece was the deadline for the show. But if there hadn’t been a deadline, I’d still be working on that piece.

ID: Would you continue to make objects for this sculpture?

NE: I mean, it’s a procession, and a march or demonstration could have millions of bodies, it could be endless!

ID: I see that in the Shape Driven Head Paintings. Those are pretty sick.

NE: Talk about modular. The paintings tell you what number they are in the series by holding up fingers and counting off, 1…2..3…

ID: That’s pretty playful. Sometimes the heaviness of ideas can take me away from its humor but I guess humor at its root is heavy.

NE: Humor can also function like the Trojan horse you mentioned, though in those “constructed” paintings there’s no ulterior motive.

ID: I wanted to ask you about the painting The Artist at Work. It’s so sensual. It’s the sexiest cubist painting I’ve ever seen.

NE: That’s the best compliment! I feel like I just won by making the sexiest cubist painting ever. (Laughs)

ID: You had me rolling with the beret.

NE: The eternal signifier for an artiste.

ID: Oh shit, Picasso getting his freak on!

NE: Picasso’s entered the conversation!

ID: There’s some plausible deniability though. You could say it couldn’t be Picasso, because Picasso wouldn’t eat pussy.

NE: (Laughs) It’s true.That selfish fucker probably never gave head, though he was especially horny so, who knows. It’s a sexy and absurd painting, Picassoesque in the idea of an artist as a lothario, it’s such a corny trope. That painting is literally about friction.

ID: That’s one of the reasons why I fuck with your work. You’re not a frictionless artist, and for what it’s worth, the work is too rebellious to be frictionless.

NE: The best art is always a rebellion. Painting is a form of non-violent misbehavior and creative disobedience that is the opposite of and in opposition to facism, intolerance and repression. We’ve seen everything already. Images glide by, we’re looking at too much almost all the time, sometimes my eyeballs feel like those slot machine numbers that spin around. I want the material of art to be sensual and textural but also abject and degenerate, I want to feel something. Is that too much to ask for?

ID: Well, speaking of the abject, I think about your Thing painting, From Success to Obscurity. I love that painting. It felt so tragic but I understood the humor of it. Like I was a kid observing the humor of a masculine teenager.

NE: I was making fun of myself and my heavy emotions, I was worried about my career pittering out or something. Some of my paintings are made the way novels might be written, they’re plotted out. The large multi-figurative paintings are made by first reading, note taking, jotting ideas, and finally drawing to get those ideas flushed out. Then it’s a process of redoing and refining, painting at a small scale before committing to a large scale. It takes forever. The whole process makes me stressed out and grumpy. It’s a different mode of working, anyhow, I’m glad you like that painting.

ID: I do! I wanted to ask you about the smaller sculptures in your show. Mad Cat is probably my favorite.

NE: It’s got attitude. I had a Saarinen Tulip chair which of course got beat up in the studio and finally broke, so the chair was repurposed to be a kind of a helmet for the cat.

ID: It feels like war. Like storm trooper, Totenkopf, skull and crossbones. It engages negative space in an interesting way. You have some clever moves.

NE: That’s a great compliment coming from another sculptor! It’s inspired by my studio cat Edie. She is actually behaving herself right now. Often she goes after my guests. (Laughs)

ID: I get down with cats. If I could transform into any animal, it would be a cat.

NE: Woah, like a big cat? Like a panther?

ID: No, like a street cat. Imagine seeing me walking somewhere and I transform into a black cat and disappear into an alley.

NE: That’s hot. They’re beautiful, powerful animals. I might like to be a cat too. Actually, I’d probably choose something with wings. I could see being like an owl. Or maybe a crow.

ID: We’re on the same page.

NE: We both picked really cool animals. Neither of us picked kangaroos. There’s a wack animal.

ID: Why do you render faces the way that you do, specifically in your sculptures?

NE: I’m trying to find a balance between not being too specific while still giving them character. Noses are fun because they stick out so there’s a humor to it. Ears too. And of course faces can have an element of self portraiture whether you like it or not.

Words by Isaiah Davis