Twiggy, Jean Shrimpton, Veruschka, Peggy Moffitt… The names of the supermodels who came of age in the swinging sixties are forever associated with images of miniskirts, pop music and sexual liberation. While these models may have been the fashionable face of the era, giving visibility to a new generation of modern women, a larger question looms around who exactly was behind the camera. Female fashion photographers were few and far between, with the landscape dominated by men such as David Bailey and Richard Avedon.

Charlotte March, who worked for magazines such as Brigitte, Stern, Elle, Vogue Italia, Vanity Fair and Harper’s Bazaar throughout the 1960s and 1970s, is a rare exception. Yet the Hamburg-born photographer remained little-known until her death in 2005, when her partner began to archive her more than 300,000 photographs to ensure that her work could be seen by a new, wider audience. It led to a rediscovery of a photographer who ranged from documentary ‘humanistic work’ on the fringes of post-war Hamburg (a city in transition during the 1950s) and her expansive fashion imagery from the 1960s onwards.

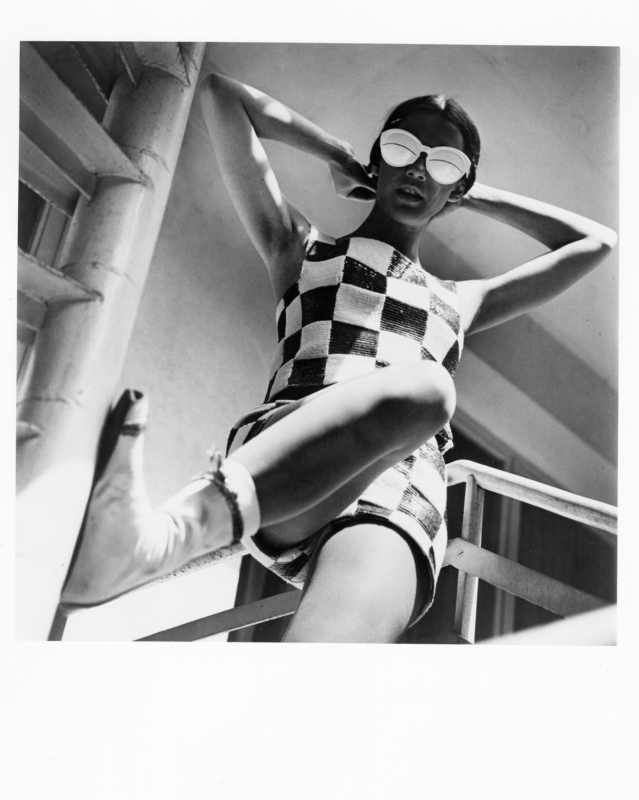

“In her mirrored eyewear is a hint at the reversal of the typical male-female power dynamic: can March herself be glimpsed behind the shutter?”

In this image from 1964, a model in reflective shades stares down the lens, her leg casually leaning against a staircase. She is relaxed, assertive, at ease. In her mirrored eyewear is a hint at the reversal of the typical male-female power dynamic: can March herself be glimpsed behind the shutter? The model looks straight at her photographer just as March looks right back at her with a female gaze. Shot from below, March raises questions about autonomy and collaboration. The presence of the photographer is fully felt in the frame.

March was acutely aware of the gendered nature of these dynamics. In 1977 she released a book titled Mann, oh Mann: Ein Vorschlag zur Emanzipation des attraktiven Mannes (which translates to ‘Man, oh man: A proposal for the emancipation of the attractive man’). With its tongue-in-cheek title and provocative, sexualised imagery, it flipped the script on the traditional relationship of male photographer and female model. With its nude shots of men on satin beds, tanned bare bottoms on the beach, and a male model on the cover biting seductively into an apple, it is telling that the book still looks out of place today even as we remain accustomed to highly sexualised images of women.

“March remains an overlooked pioneer of photography, and introduced a new perspective on what female emancipation might truly look like”

March remains an overlooked pioneer of photography, and introduced a new perspective on what female emancipation might truly look like. In her images she encouraged her female models to embody an independent and even contrary attitude to the dominant gender politics of the time. They are shown drinking beer, smoking, looking down to the lens, or lounging outdoors with careless abandon.

Throughout her work, March offered a reminder that a photograph is never just a photograph. The conditions in which it was created are key, she suggests, and who is behind the lens matters. Which is all part of the fun.

Louise Benson is Elephant’s deputy editor

Charlotte March: Fotografin/Photographer is at the Sammlung Falckenberg, Hamburg until 4 September