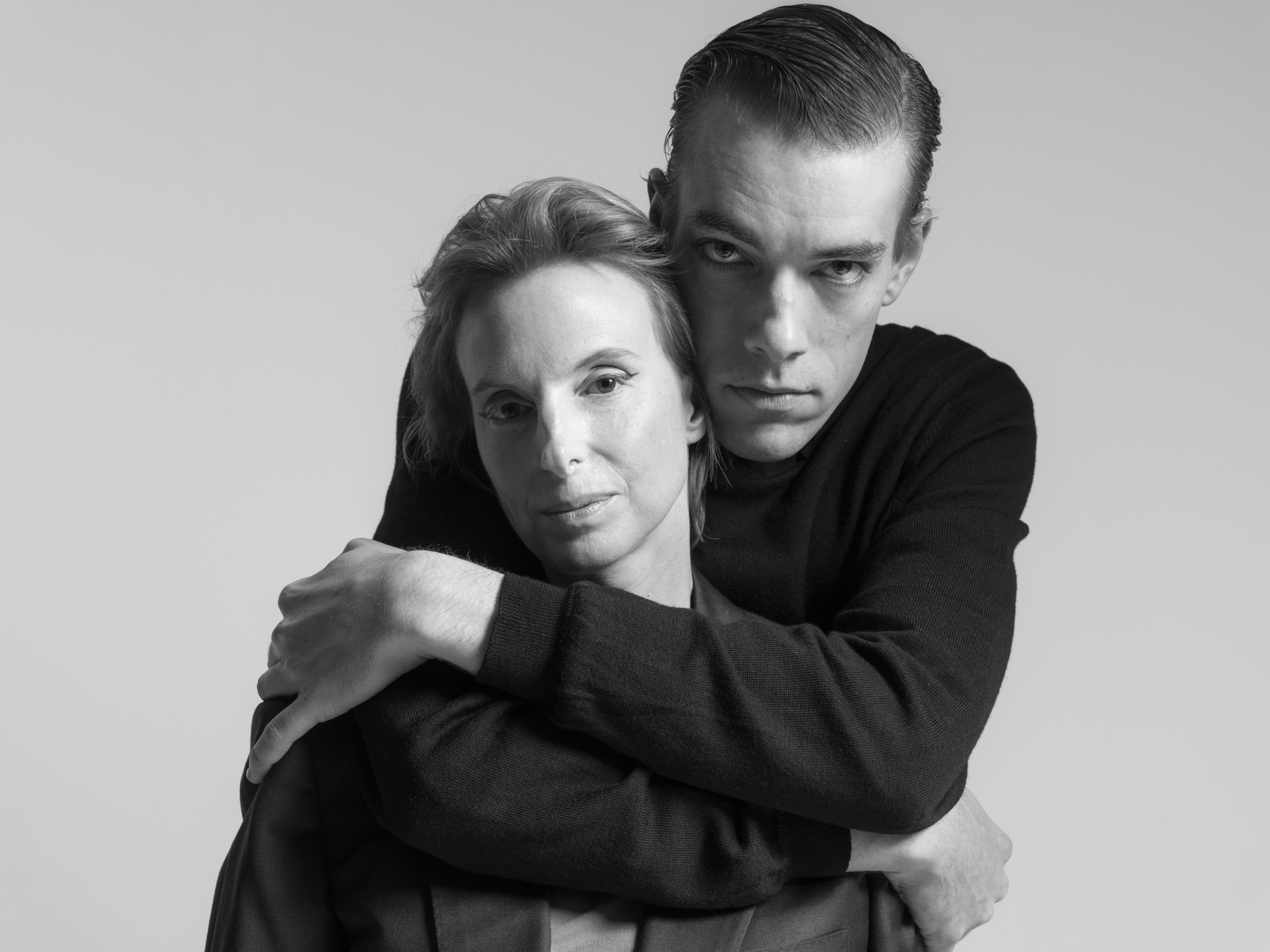

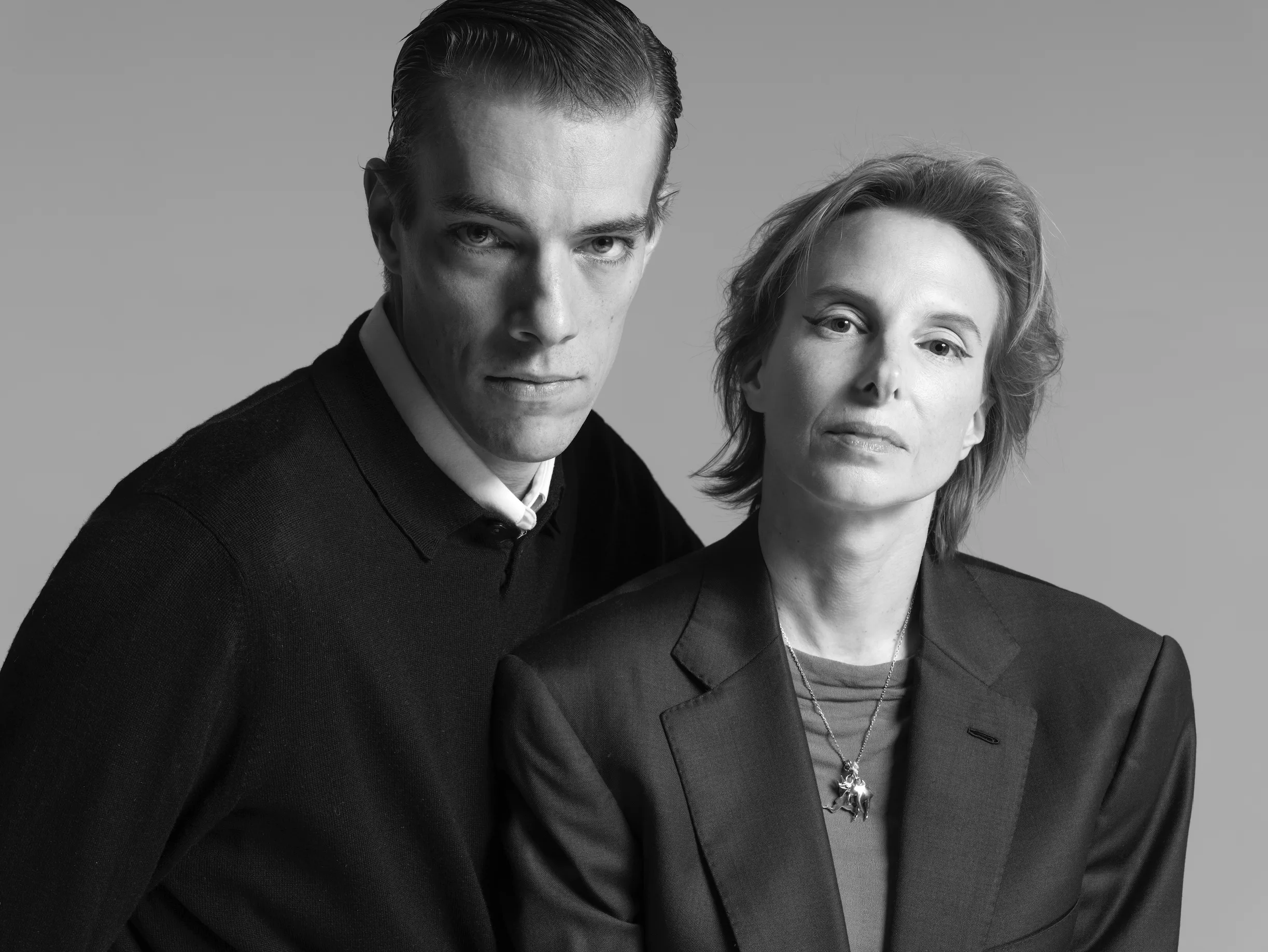

Camille Henrot and Mauro Hertig discuss navigating partnership as both intimate collaborators and independent creatives. With photography by Brigitte Lacombe.

Camille Henrot and Mauro Hertig navigate distinct creative paths, each exploring the complexities of human existence through radically different mediums. While their practices are independent, their shared life as partners informs a nuanced interplay of ideas, offering a glimpse into how intimacy and individual creativity can coexist and occasionally intertwine.

From literature and poetry to cartoons, social media, and the banality of daily life, Camille’s work draws on a wide range of influences to explore the complexities of being both a private individual and a global citizen in an increasingly interwoven world. Her multifaceted artistic practice spans drawing, sculpture, video, installation, and film, delving into themes such as intimacy, care, and the overwhelming structures of modern life, while resisting confinement to any single material or genre. Central to her practice is a deep concern with how various forms of knowledge, both empirical and subjective, are structured and understood. Rich in contradictions, her art juxtaposes fragmentation and humour, offering a nuanced reflection on the intersection of the personal and the universal, where inner and outer worlds collide. In her current show A Number of Things at Hauser & Wirth New York, she examines the fluid nature of human behavior, this time focusing on how instinct and control intertwine. As an extension of Henrot’s ongoing interest in relationships of dependency, her figures embody domestication and attachment.

Mauro’s body of work is rooted in the delicate interaction of sound, space, and narrative. A composer and performer, Hertig is currently working under the alias Xol Meissner as he prepares to release his new record, Excess of Loss. He blends his classical training with an experimental edge, creating pieces that defy easy categorization. His diverse output includes ensemble, chamber, and site-specific compositions, with a particular focus on exploring interdependence through decentralized settings. By designing stage environments that distribute agency, Hertig incorporates intimate sounds like speech, touch, and instructions into his sonic landscapes. Whether crafting evocative pieces inspired by physical phenomena or collaborating with musicians, his approach to music is both cerebral and emotional.

Driven by individual vision, Camille and Mauro’s practices are personal, yet their shared life offers a backdrop to their work. Even their reading lists provide insight into their intellectual worlds: Friedrich Nietzsche’s Zur Genealogie der Moral (On the Genealogy of Morality) sits alongside The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow—both of which challenge dominant narratives about the inevitability of hierarchy and inequality, emphasizing the role of human agency, creativity, and historical contingency in shaping moral and social systems.

Writer Zeynep Gülçur spoke with the artists about how they balance being both confidants and critics, the way their shared life and mutual influences shape their creative practices, and the songs that each feels best encapsulates the other.

Zeynep Gülçur: It’s intriguing to learn about an artist’s work through the lens of someone closest to them, especially when that person is also a creative. How would you describe your partner’s work from your unique perspective?

Camille Henrot: About your work as Xol Meissner, I would say deep, tender, romantic and dark.

Mauro Hertig: I always thought there was a seductive surface in your work which invites you to go deeper. The deeper you go, the more wild and sometimes violent, or distorted, it becomes. The unique perspective as a partner can be deceiving though—knowing someone so well might not necessarily be helpful when approaching their art.

CH: Yeah, there’s a lot of interesting feedback about that from the children of artists, the way artists’ estates are being run. Sometimes, if it’s only the family, it’s a disaster. You need people from the outside, museums and a curator or somebody from a completely different field. It’s not always the person you live with who understands your work the best.

ZG: What is your individual creative process like? How does it differ from or align with your partner’s process?

CH: I read a lot, several books at the same time. I have quite a compulsive approach. I also collect a lot of images. The process differs if it’s a film, or if it’s a sculpture project, or a painting. When it’s painting, I print a lot of reference images and flip through them in a binder in preparation to paint. I need sweet treats also—I will have a very concentrated chai and put on a playlist. For all the other projects it’s a longer process, where it is a combination of compiling music, compiling images, reading different books, asking people for advice.

MH: I write lyrics in the subway or while walking through the city. When it comes to creating the music, it’s always in a quiet room alone. No interference, no one else. I even have a little soundproofed telephone booth inside my studio which I lock myself away in when the neighbours are too noisy, or when the ice-cream truck is in front of the building.

CH: It’s funny that you, being super tall, fold yourself into the mini chamber, and I’m the tiny one running around in my big space, never sitting, with people floating around—never, never seated and always kind of like a little ant, running around.

MH: It’s like a comic strip—we are cartoon characters.

ZG: Do you ever create together in the same space, or do you prefer to keep your creative practices separate, maintaining a distinction between work and home life?

MH: We work apart, but I think both of our work draws a lot from life together, at home. The way you interact as a family, the conversations, the dependency, it all finds its way into the core of what we create.

CH: We’re always separated for work. First of all because you need complete silence, while I need very loud music. The places of production where we work are in different parts of New York as well; you go North, I go South.

ZG: Given your boundary-less approach to art, do you find that your work naturally interweaves—drawing from shared ideas, books, lived experiences, or mutual inspirations—even when working separately? Or do you see your work as distinct and independent realms?

CH: I think it is about weaving. For example, when I was working on my book of essays Milkyways and paintings from System of Attachment, both of which addressed the experience of caring for small children, you did this music piece called Mum Hum. Naturally, we talk about the books we are both reading, so there is definitely mutual influence. But we both have our independent trajectory. It is the cross-contamination that you would expect from people who see each other often.

MH: Mum Hum, which has musicians communicating through a tin can telephone, definitely came from inquiring about how fetuses perceive sound, and how they use it to understand the outside world. From month six onward, a fetus has quasi-fully hearing organs. We were reading the same articles and books when we had the kids. During that period, you did a series of drawings based on ultrasound imagery, and I went down this path.

ZG: Is there a piece by your partner that moves you the most? If so, what about it speaks to you, emotionally or conceptually?

CH: I love your song Breeder a lot. Every time I hear it, I have new images popping up. It’s very cinematic, and I have it in my head after your concerts.

MH: I think for me it’s the drawings in general, because I feel like they’re the most raw and direct way for you to communicate. I love them all, especially the ones from System of Attachment, and the Tropics of Love series from a bit earlier.

ZG: How does your understanding of each other’s work evolve over time? Do you notice any shifts or new influences on your practices as your relationship deepens?

MH: Oh, that’s a big one. You see how your partner changes, how their work changes. You’ve always been somebody who works through many different channels, and what I get to see from them is a bit like jumping between five fast-moving trains—Oh, so this is how the paintings have evolved—and here is a new series of drawings—and the sculptures have got a new twist. It is quite magical. Also, you work so fast!

CH: Your career has evolved in the past year with this new project as singer Xol Meissner. It’s a new facet of you that I’m discovering. The influences I see in there, like Nick Drake, Scott Walker, Arthur Russell, are some that I understand better than the strictly classical music references from before. I’m more able to talk about it and enter in dialogue with it.

ZG: What is it like to co-create a piece artistically? How does this collaboration compare to others you’ve experienced?

CH: I think it’s difficult to co-create a piece artistically. In a couple it can be tense because you always need somebody who has the final cut, who gives an overall direction—a captain of the ship, basically. There is a power dynamic. Plus, it’s not like we are all dancing in a big field of grass with flowers—we don’t agree on everything all the time. So, somebody with the final card is required, otherwise it’s not really productive.

Sometimes it’s like playing ping-pong. This was my experience with the collaborative piece Buffalo Head: A Democratic Storytelling Experience, which I did for Vulcano Extravaganza in 2016. When I collaborate with a writer, it’s different, because we are never in the same room. I can offer key words and direction, and they come back with their own interpretation. With music and film, it’s a little more hands-on. For example, when I commission a soundtrack for a film or for an art piece, I have a lot of quite precise, but very different, mini-directions and bubbles of ideas. I operate more like a film director in that case. There are many different types of collaborations—it’s a vague word, because it doesn’t always mean everyone is equal and participating in the same way.

MH: Pretty much agree with all of this. A playful ping-pong dynamic can work well in any constellation. When one is the boss it tends to get more tense, because it goes against the equality of a loving relationship. If you do it, you risk creating a mess. Are we going to create a mess with your upcoming film?

ZG: If your partner’s creative practices were a song, and I couldn’t resist asking this, especially with Mauro here, what kind of song would it be?

CH: Roxy Music’s Avalon—masculine voice with feminine energy, hesitations, unstable. Someone rocking you softly…

MH: Laurie Anderson’s Bright Red.

ZG: The interplay between intimacy and critique is a unique facet of being partners. How do you navigate the dual roles of being each other’s closest confidant and, at times, the most honest critic within the art world? Or is the feedback more self-contained?

MH: I do feel like we’re both quite honest and open. Maybe you’re holding yourself back… We are very supportive of each other in general. I am very proud of your work. Whenever there is a new series of paintings, or a new set of sculptures that you show me, it makes me happy.

CH: As artists, you’re so vulnerable. Artists in general, like me and you, we are both so vulnerable and the world is so full of criticism that, mostly, we think more about how to support each other. Sometimes critique is helpful, but there’s only a very specific moment for it. The percentage of artistic critique in a relationship is, like, three percent—very small, like the grain of salt in a giant pot of ninety-seven percent sugar.

ZG: If you had to choose, would you rather have your partner’s artistic talent or their ability to stay calm during a deadline crisis?

CH: That’s an odd question! Do you want us to get a divorce? Neither of us is calm during a deadline crisis!

MH: Although I’m actually kind of calm during a deadline.

CH: No, you’re not…

ZG: As a final question: is there a book that has particularly resonated with you? Are there any quotes that continue to echo in your mind?

MH: I’ve recently been re-deep-diving into Nietzsche. I love this quote from his Genealogy of Morality, which translates to something like: Justice is the good will among similarly powerful people to reach an agreement, to “agree” with one another via an exchange—and, when relating to a group of people with less power, to force them into the same exchange among themselves. It’s very much applicable to our current challenges in the arts, but also wider politics and class struggle.

CH: I’ve been thinking about this quote from The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow: Police, the city, civilization and civility are connected. So, there’s a reason why in English the word ‘politics,’ ‘polite,’ and ‘police’ all sound the same. They are all derived from the Greek word polis, or city. There’s a political implication in the idea that civilization comes from a form of a constraint, a form of self-discipline. I think this is a key factor when thinking about the future of civilization. I’m currently working on ideas around etiquette, and this book has been so resonant for me, even though I’ve been playing with more old-fashioned concepts, like how to fold your napkin or when to remove your hat. I always felt there was some underlying political implication behind these kinds of rules. In my opinion, Graeber’s book should be taught at schools. It’s a major piece of work.

Words by Zeynep Gülçur

Photography by Brigitte Lacombe

Camille Henrot’s exhibition A Number of Things is on view at Hauser & Wirth Gallery New York until 12 April.

find out more