On the eve of their joint London exhibition, the two artists invoke a collective state of consciousness capable of holding history accountable for its colonial legacy and rekindling the magic of non-Western artistic tradition.

Stepping into the room hosting Kader Attia and Mandy El-Sayegh’s collaborative exhibition Disfigurations feels like entering a tapestry of meaning. The densely woven threads appear as physical embodiments of the research-led, intersectional analysis culminating in their respective practices. Open at London’s Lehmann Maupin between September 21 and November 4, the showcase is conceived as an artistic dialogue between the pair’s investigation into the themes of colonialism, the exponential spread of the attention economy and the omnipresence of contemporary visual culture. In the hands of Attia and El-Sayegh, art becomes a means to scrutinise, dissect and reassemble the hegemonic narratives that determine our perception of the world. Proceeding in an almost scientific way, they delve into the centuries-spanning, global archives to bring to the surface those subjects whose existence has been overshadowed by the prevailing of the West over non-Western countries. Through their manifold exploration of colonialist legacies, as well as politics, economy, pop culture and the body, Attia and El-Sayegh make manifest the obscured, inviting the public to question the factuality of the frameworks of thought through which they decode their surroundings.

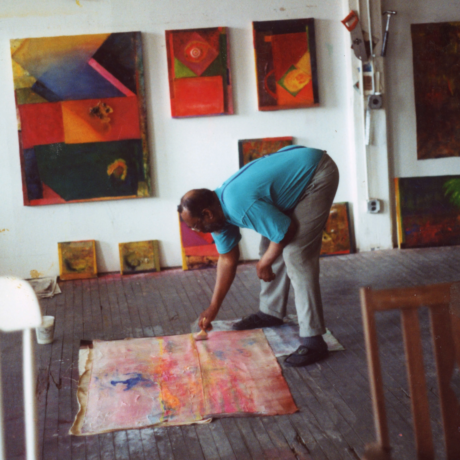

An artist and curator, Attia was born in Dugny, France, to Algerian parents in 1970. Raised between the outskirts of Paris and Algeria, the interdisciplinary creative and Prix Marcel Duchamp winner (2016) describes his craft as a result of his multilayered experience of identity. Encompassing sculpture, photography, installation and video, Attia’s work draws on his culturally rich outlook on society—which he honed while living in Congo, South America, Paris and Barcelona—to examine the link between individual nations and their histories in relation to issues such as social injustice, deprivation and suppression, violence and loss. Intent on demonstrating how each country’s past, present and future can only be understood by acknowledging the reciprocal influence that every state exerts on the others, over the years, the Berlin-based artist began to look at collective memory as a valuable alternative to one-dimensional, arbitrary accounts of history.

Since the 2000s, his oeuvre and philosophical writings have centred around his conceptualisation of the notion of repair, which sees both nature and humanity as driven by recurring processes of injury and recuperation, loss and recovery, destruction and creation. In many of his artworks, from Untitled (Repaired broken mirror, 2013) to Traditional Repair, Immaterial Injury (2014–18) and Some Modernity’s Footprints (2018), this idea is rendered through visible stitches emphasising a previously open wound in Attia’s materials of choice. Like scars, they stand as a reminder of the rifts—whether physical or metaphorical—undergone by the subjects of his pieces. The artist’s production redirects the attention onto the long-lasting grievances endured by those whose contributions to history, art and the wider sociopolitical discourse were erased by colonial powers and their outliving infrastructures.

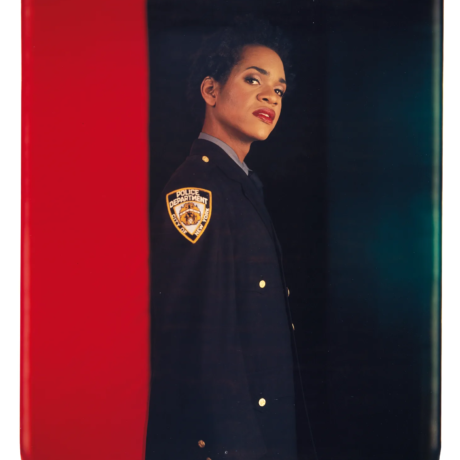

This eternal cycle of fracturing and recomposing provides the foundation for El-Sayegh’s multidisciplinary practice. From layered, large-scale paintings to sculpture, film, sound, installation, writing and performance, her craft leverages the ability of different media to absorb the audience in reflections capable of disrupting their understanding of the ruling systems of order. Highly methodical and provocative in its essence, the London-based artist’s work utilises found objects, personal items, as well as excerpts retrieved from mass media and visual culture to expose the building blocks of aesthetic as well as social and political consensus. The daughter of a Malaysian Chinese mother and a Palestinian father, El-Sayegh was born in Malaysia in 1985. Having moved to the United Kingdom at the age of five, her gaze on the world is inherently influenced by her experience of displacement: an aspect of the artist’s biography that brings her closer to Attia’s fluid, many-sided conception of identity.

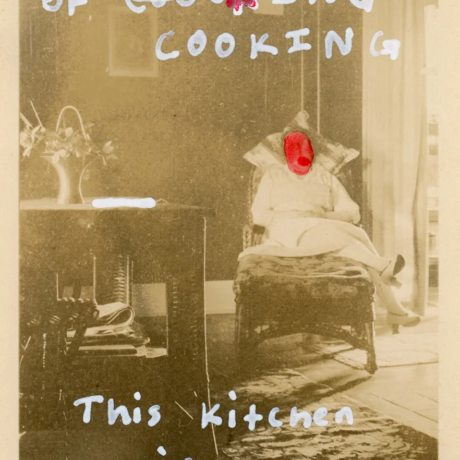

Consisting of an intricate reworking of source materials including newspaper and magazine clippings, vintage and present-day ads, currency symbols, contrasting depictions of womanhood and more, El-Sayegh’s creative offerings superimpose intimate and collective mythologies onto a stratified critique of contemporary society. Her canvases often mimic the tones and easily bruisable texture of skin, establishing a direct connection between the body and the geopolitical and societal issues orchestrating its role in the public space. Setting herself in contrast with the values symbolised by “white cube” art spaces, El-Sayegh readapts her multimedia installations so as to revolutionise the atmosphere of the institutions hosting her shows, the latest example of which was her recent solo exhibition at London’s Thaddaeus Ropac, Interiors. Expanding over the entire walls and, often, floors of the galleries presenting her work, her creations move beyond the expectations of contemporary art by rejecting trivialising stereotypes traditionally forced upon the production of women and non-Western artists.

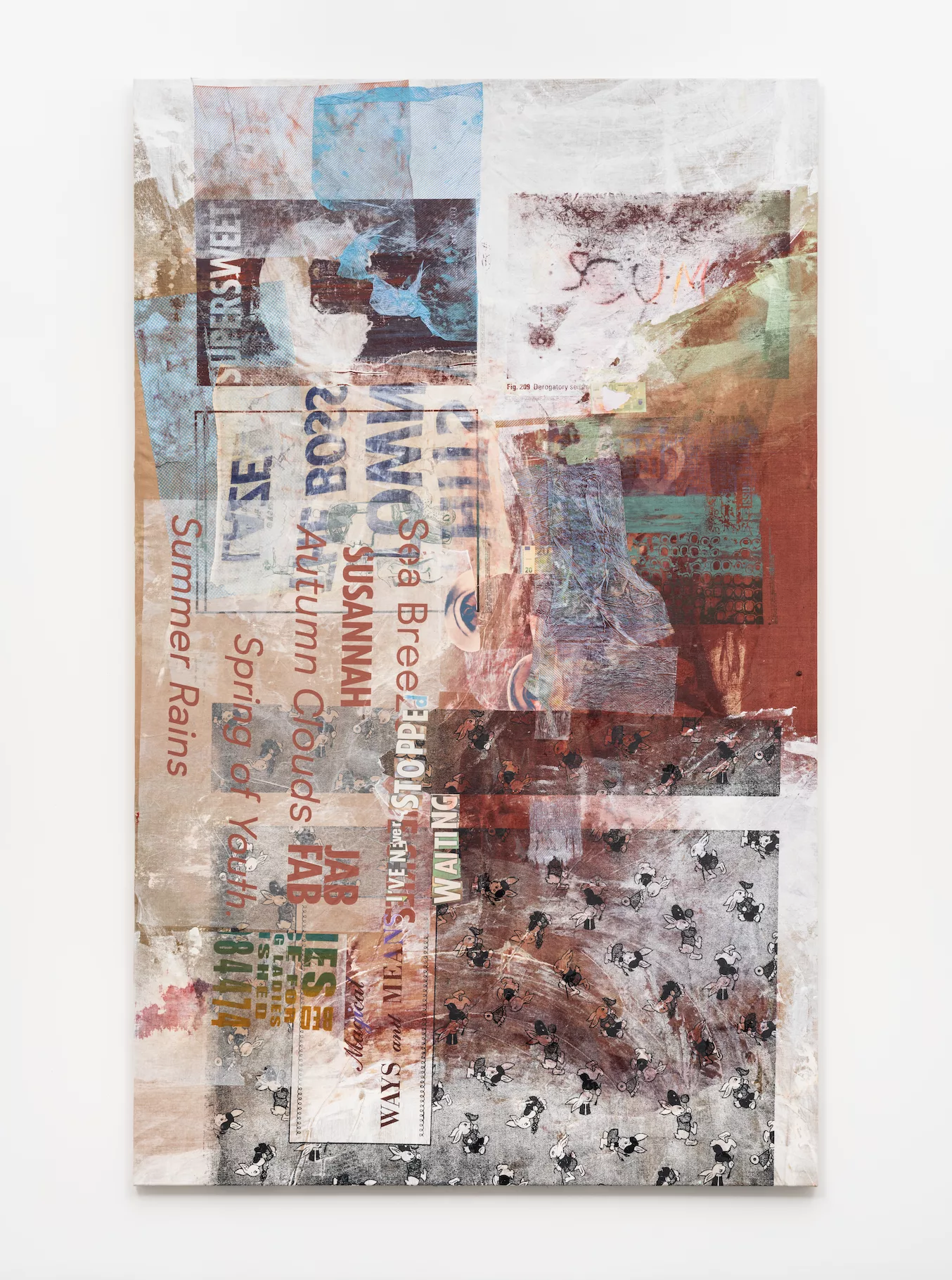

With Disfigurations, the two bring viewers to face the irremediably complex and fragmented essence of subjectivity through a selection of site-specific paintings and mixed-media sculptures. Within the showcase, Attia’s critically acclaimed Mirrors and Masks series—a group of mirror-encrusted replicas of African masks collected and repurposed by Attia over the last 15 years—provides a kaleidoscopic experience of El-Sayegh’s image-rich, collage canvases. Through this shattering of perspectives and traditional vantage points, the artists appeal to the audience’s individual sensibility to fill in the gaps legitimised by the selectivity of historical and artistic representation. From image cut-outs and pornographic screenshots to decontextualised headlines, hand-painted details and silkscreened ephemera, El Sayegh’s hypnotising paintings are charged with questions concerning sex, womanhood, heritage, memory and legacy. Amplified through the reflecting facets of Attia’s patchwork-like, ancestral masks, these works translate today’s fluctuating and mediated notion of the self while simultaneously standing as a reaction to the West’s “amnesic memory of the history of non-Western cultures”. Below, the artists reflect on the trigger behind their process of creation, the decolonisation of the art world, and “movement as the essence of life”.

Mandy El-Sayegh: I don’t think you can choose whether or not you want to become an artist. If you’re an artist, you’re an artist. And this is so because there’s a lack in the language that’s available to us, so you’re forming your own discourse out of necessity. Well, at least that was the case for me.

How was it for you, Kader?

Kader Attia: Being an artist isn’t something you can decide or choose: it’s part of who you are. I believe we’re never really I. Nietzsche says that it’s the Us that constantly speaks and manifests itself through the I. We’re never just ourselves, we’re never just our own persona. We embody multiple entities and identities.

ME: Exactly, and that multiplicity is reflected in the language that we use. In Indigenous, Filipino psychology, for example, they have the word kapwa for the I and the You and another term to address the collective. So depending on which language you speak, the perception you have of yourself and your identity, your I, changes as a result. Because we have the vocabulary to describe colour, then we get to perceive colour, but this wouldn’t happen otherwise. A similar process influences our understanding of identity.

What would you say is the drive behind your work?

KA: I always find it difficult to describe what I do. I can’t summarise my work without stressing that I didn’t get to the concept of repair by chance; it’s an idea that came to me after years of research at the beginning of the 2000s and it perfectly reflects the vision behind my practice. My desire to fix objects was innate. As a kid, I would build my own toys out of discarded materials and find new uses for things that had broken. Later, through studying philosophy, I learnt about the human inclination to cyclically gather and separate things, gather and separate things … on an eternal loop. I also realised that anytime something underwent an injury, humans would stitch it back together. And I think that process has a lot to do with what’s happening here at Lehmann Maupin today, between these walls, with our show Disfigurations—particularly when we look at the different parts of your compositions, Mandy, how they propagate and expand even further through my mirrored masks in this sort of mise-en-abyme. It’s something that moves me at a deeper level, this process of creation, the passage from the ‘before’ of the object to its ‘after’, before the nothingness and after the nothingness, when you suddenly give life to something new. I see it as yet another form of repair, and that’s why I always invite people to examine my practice through this concept, because it pushes me forward every day.

ME: I really resonate with what you just said. My dad has always loved fixing electronics—he does amateur radio. For him, it’s all about taking different components and rebuilding. When I was growing up, he would play around with radio signals, trying to make new connections with things. And that’s probably why today my practice places great emphasis on collecting, gathering and assembling, whether in the literal or metaphorical sense, in relation to different spaces, conversations or urgencies. When I’d just graduated from art school, I didn’t think that that kind of approach to art was even a possibility. My parents didn’t have access to ‘high culture’, so I never thought that making a career out of art was something one coulddo. My mum worked as a midwife, my dad fixed computers. After graduation, I became a carer, which put me in a different relation to another body for the very first time. Even in my own practice, this idea of helping, repairing and supporting is, in a way, always present.

KA: I think today we’re witnessing a global momentum that sees the question of identity as a process of ‘return’ to something: something we often can’t even explain ourselves, as it transcends univocal explanations. That quest for a different kind of identity contributed to making this exhibition happen. Quite literally, Disfigurations sets itself in contrast to figuration, which is a large chapter of Western art history. The showcase is a direct response to my Mirrors and Masks series, a project where I intervened on replicas of African masks by plastering fragments of mirror onto them. The trigger for this body of work was the retrospective on Picasso that Paris’s Grand Palais hosted in 2008, called Picasso and the Masters. I visited it and truly loved it. It featured over 200 artworks by Picasso himself and an incredible selection of great masters, so it couldn’t disappoint. Still, to my surprise, the exhibition didn’t include a single African mask. I say “surprise” because we all know that Picasso was inspired by African art, so the decision not to include any African artefacts seemed suspicious.

Back then, no one was talking about decolonising the museum; the restitution of looted artworks held in European institutions and collections was still only a mirage. I decided to send a letter to the curator of the retrospective to flag my concerns. When I tried to explain that Picasso had drawn on African masks, no one involved in the exhibition seemed to know anything about it. So I went back home and that’s when the idea for Mirrors and Masks came to me. For years, I’d been collecting cheap replicas of African masks at different markets and tourist shops. Over time, I’d amassed a good selection. One day, I began to play around with paper, making different kinds of angles with it. From there, I tried to apply those same angles onto the masks so as to fracture their surfaces into different elements. Somewhere along the way, I decided I wanted to do the same, but with bits of mirror this time. The end result left me speechless: filtered through each and every one of those pieces, the reflection appeared as if completely fragmented. Suddenly, I understood how Picasso had been able to envision his cubist paintings.

I don’t look at Disfigurations as a mere art exhibition; for me, this show is activism. The goal was to conceptualise a series of artworks that would involve people as if they were Picasso watching, and then recreating, an object. When you look at yourself through the reflection of those masks, it feels like staring at one of his canvases. The universal experience that comes with this show is what makes it a great opportunity to address a political issue such as decolonisation. A continuation of my research on repair, the exhibition strives to foster a democratic conversation on the erasure of non-Western art from history and art history books. I wanted to prove to everyone who thought Picasso didn’t have African art among his influences that they were wrong simply by having them look into one of my masks. What I truly aimed for was a narrative shift acknowledging the role of non-Western tradition in the evolution of different art forms.

ME: In paintings like Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), the masks were literally part of the composition, and yet people still denied it. I’ve always been interested in the concepts of over-visibility and underrepresentation; how certain subjects in society don’t get to have a direct influence on the archival information that’s passed on from generation to generation, whereas others dominate the discourse. The very people whose contribution has been unacknowledged throughout history are nonetheless somehow present, although quietly and exploitatively, in the art that we consume. My methodology is quite straightforward in that sense: I reinsert the figures that have been systematically removed from history into the narrative. Layered into the paintings I created for Disfigurations are a lot of Israel Defense Forces’ (IDF) operation names, which are seasonal words, like ‘Summer Rains’, ‘Orchard’—very whimsical-seeming terms. It’s a play on what we’re allowed to see and what, instead, gets obscured. I identify the things that were foreclosed in the shaping of history and turn them into the focus of my canvases.

KA: One of the most refreshing aspects of this showcase is having the opportunity to witness how differently each visitor responds to the artworks on display. A couple of people told me that the masks I created saved their lives. One woman in particular opened up about a mirror experience she had as a child, which continued to haunt her for years, and I felt grateful for her willingness to share such a personal story with me. She was a psychoanalyst, so she went into Lacan’s theory of the Mirror Stage, which talks about the moment when a child first becomes aware of its body by looking at its reflection in the mirror.

The fact that the fragmentation of perspectives captured by the masks successfully amplifies the non-mimetic tradition of non-Western art makes Disfigurations even more relevant. Contrary to what happens in the West, non-Western artworks don’t strive to repeat the real world, which is probably why the feedback I received from the international artists who’ve seen the masks—whether from Africa or Germany—was so incredibly varied. While the experience of the exhibition is certainly subjective, I tend to look at the attention that any human being puts into a piece of art, a film, an article, or whatever that might be, as something collective. And that’s because, in the economy of attention we live in, we tend to dedicate attention to similar things. Our interests don’t overlap completely, but there is a general understanding of what’s worth devoting time to and what isn’t, and that brings us closer together.

Going back to the concept of the exhibition, I wanted to mention the myth of Narcissus, which I find extremely meaningful for the kind of moment we’re currently experiencing as a mass. Nowadays, with social media, we constantly create and share portraits of ourselves in order to feel closer, or get a better sense of, the person we are. Or at least, that’s what we tend to tell ourselves to justify such behaviour. But what happens when our portrait doesn’t actually live up to the idea we had of ourselves, or the reality of our persona? Disfigurations taps into the psychoanalytical level of that dilemma, which is something many of us can relate to.

ME: Think about how it can feel to walk into an art show without necessarily understanding what’s going on within it. With Disfigurations and, specifically, the mirrored masks, we give visitors a hook, something to cling onto, which allows them to recognise themselves as part of the exhibition. This ‘mirror stage’, if you will, doesn’t only see them participate in the showcase as a visitor, but also as a subject of the artworks themselves. As social media continue to force their way into our experiences, these questions around reflection and recognition will become more and more prominent.

KA: Disfigurations is, ultimately, a conversation between our practices, a merging of our perspectives on things. In an era where algorithm-driven governance is using facial control to keep track of our behaviours, preferences and movements, the title of this showcase stands as an alternative to the reality that’s imposed on us. I find it fascinating: to me, ‘disfigurations’ represents the pharmakon—what in ancient Greece was seen as both the remedy and poison of society. It’s something we can’t escape from, but have to come to terms with. In this exhibition, you and I use disfiguration as a pharmakon to fight against computational data governance. Technology is a pharmakon, too, because it opens up a whole universe of possibilities to us, but it also fractures our subjectivity into millions of pieces to extract as much of our information as possible. It’s a process that transforms us and our identity permanently. In fact, we might even argue that there is no such thing as individual identity today, not anymore. I don’t believe in identity. As Martinique-born author, poet, philosopher and literary critic Edouard Glissant once said, we were born in one place, we live and work in a second and third place, and we will die in a fourth or fifth place.By ‘places’, he meant cultures.

In today’s globalised world, the bourgeoisie of Shanghai has access to the same services as New York’s, so what is the meaning of identity, of culture, in 2023? It’s a fundamental question to me, especially at a time when multiple online “echo chambers”—as American legal scholar Cass Sunstein likes to call them—whether inhabited by the far-right or the far-left, are advocating a return to identity in its most traditional sense. With Disfigurations, we prove that such things can, and should, no longer exist. Because we’re all different, then we’re all the same, in the sense that we’re all subjected to the same experiences. And I think this is a stance that we need to protect, especially here in Europe, where several countries are still passing laws affecting LGBTQI+ communities, refugees and other disadvantaged groups. The idea that identity still exists to me is incredibly … I don’t want to use ‘colonial’, so I’ll say it is incredibly modern. And we should move away from it.

ME: Whenever I hear the term ‘identity’, I recoil. I think it’s important to resist the coercion to speak a personal narrative, even when I feel myself going into it. There’s also this belief that women artists are known exclusively for their worst or most painful stories, rather than for what their work evokes in people, which is why I try to stay away from that as much as possible. What is universal, however, what makes us all the ‘same’, is that we’re all lacking something, and we’re all mobilised by that void. Like you said before, with your work, you go from being an artist to being an activist. Art always happens alongside revolutions; it doesn’t influence them, but it evolves in parallel with them. While I don’t see myself as an activist, I choose to work from the wound. My colour palette in itself is informed by wounding. I look at bruising and lacerations, and all of these things make me strangely happy because they allow me to acknowledge the experience of pain, rather than being fearful of it. I fall asleep in horror films and true-crime documentaries because they enable me to process things, whereas watching emotional stuff gives me nightmares [laughs]. But then again, ask me if I accept what’s happening in Palestine, my father’s homeland, or if I’ve come to terms with our impossibility of visiting it and reconnecting with other members of our family, and the answer can only be no. I’ll never stop waiting for things to change.

KA: I’ve always believed in the power of art to change society or, at least, I’ve always wished for it to do so. But when it comes to violence and, specifically, racist attacks like the one that saw a French police officer take the life of a 17-year-old boy of North African descent this June, doubts begin to arise. In the past, I worked on moving-image artworks and films addressing such issues, but the question is, can art ever outdo crimes committed by a state? Can it ever succeed in actually showing what we did wrong and how we could be better? One of the biggest problems for artists dealing with these sorts of topics is that, by addressing violence, crime and death in an exhibition space, they contribute to their fictionalisation. To me, this is one of the most urgent discussions that needs to happen within the contemporary art scene.

But the only way to find an answer to these sorts of questions is to keep interrogating ourselves about them. I think the worst thing for art is to become its own teacher. If we keep the toughest discussions out of the art world, then we leave the door open for pseudo-academics to come and teach us. We’ve finally reached a point where we can see how art has, somehow, contributed to evolution, how it has changed us. I’m not saying that art has directly changed society, but it has planted the seed in people’s heads so that 30, 40 or 50 years later something could grow out of it. And that’s precisely why I think that it’s time for contemporary art to move beyond the topics of our era—gender, climate change, police violence, capitalism and so on—which are often used as mere tokens rather than as substantial themes, and reinvent itself in a more honest, constructive way.

ME: And this leads back to the notion of repair. How do you think we, as artists, and cultural institutions can contribute truthfully to this process of healing?

KA: First and foremost, I think we should all give more of a platform to the debate on the restitution of looted artefacts, which is a conversation that allows us to address so many other issues that are, at their core, interconnected. We can talk about feminism, for example: few people address the fact that many of the African sculptures hosted in European institutions and collections portray female divinities. It’s a very complex topic. People like the cultural and literary critic and researcher Karima Laachir argue that simply sending an object back to the country where it belongs erases the magic and spirituality that lie in the artwork itself. And that’s because the mere restitution of it allows European museums to rid themselves of the guilt that comes with its history. So what are the alternatives to the sterile repatriation of colonial artefacts?

In this regard, Christine Théodore, a French psychoanalyst, says that giving back the objects isn’t enough as it doesn’t heal the trauma triggered by their plunder. Those objects are symbols of a chapter of history and need to be treated as such. There are multiple ways of looking at it, but the most important thing to know is that, as worthy as it is to participate in the debate, artists alone won’t be able to find a solution to the restitution issue. There have already been episodes where, instead of just sending things back, the receiving community has mobilised in collaboration with the institutions involved to create symposiums, performances, art activations and exhibitions dedicated to the return of such objects. To me, that’s one possible way of tackling this dilemma: we should look at it as an opportunity to come together in the name of art and history. We need to find ways of reviving the intangible, the fragments of history, of life, that have been taken away from those artefacts by envisioning solutions that can reignite their legacy and narrative for the generations to come.

ME: I like this way of reading the experience of restitution. American Middle East studies scholar Stephen Sheehi talks about not allowing these discourse initiatives to become a site for further violence. Let’s take the example of Israelis and Palestinians. Imagine that the country giving something back is Israel, then those who are in power would be the ones informing the question of how to go about it. But when you allow those in a position of power to influence such discourse initiatives, it can quickly become a trap. So, to me, this more democratic way of conceiving the process, which promotes further discussion on it rather than providing any direct answers, can also become quite an insidious territory for secondary, or tertiary, trauma. Instead, I like what you said about reigniting the imaginary associated with the looted artefacts, because that option doesn’t just involve a repair, but presupposes some sort of movement towards something other—a new direction.

KA: But you know, Mandy, repair is movement. Movement is all it takes to repair something, or someone, that has had an injury. And that’s why, when Dawn Davidsen said, “We need to reinvent the experience of restitution”, what I gathered is that we need to preserve the movement, the energy, that lives on in them, the very movement and energy that would die instantly if someone were to send those works of art back without even acknowledging their past. I find this interpretation much more interesting as it looks at movement as the essence of life. It is intangible, yes, yet much more open to diversity as a result. Movement for me is going forward, not backward. And going beyond, finding new territories and ways of exploring art, is precisely what we need in the current climate.

Written by Gilda Bruno