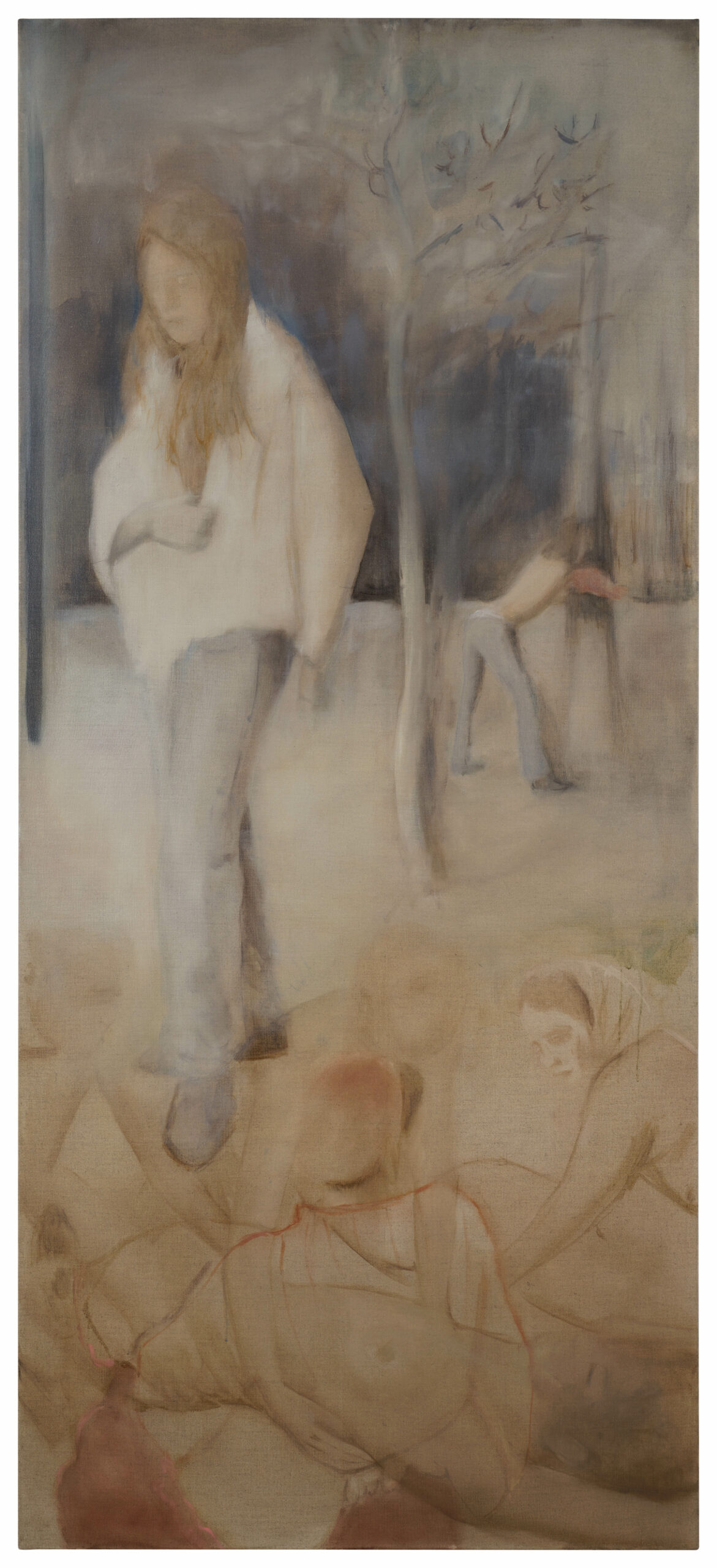

Joanna Woś does not paint explicit scenes of female empowerment, nor does she paint the kind of image which is easily digestible among the torrent of ephemeral imagery driven by social media. Even when concentrated on a computer screen, as I see them, her works are slow to divulge themselves; diluted and thinly painted layers gradually reveal various perspectives. Looking is an eternally focusing but never quite focused camera. It is this which makes Woś’s paintings particularly beautiful but also so disquieting since their scenes are often those of unequal power balances, violence and/or perversity. They prod the line between the aestheticisation of abuse and the indelible, uncomfortable nature of the truth.

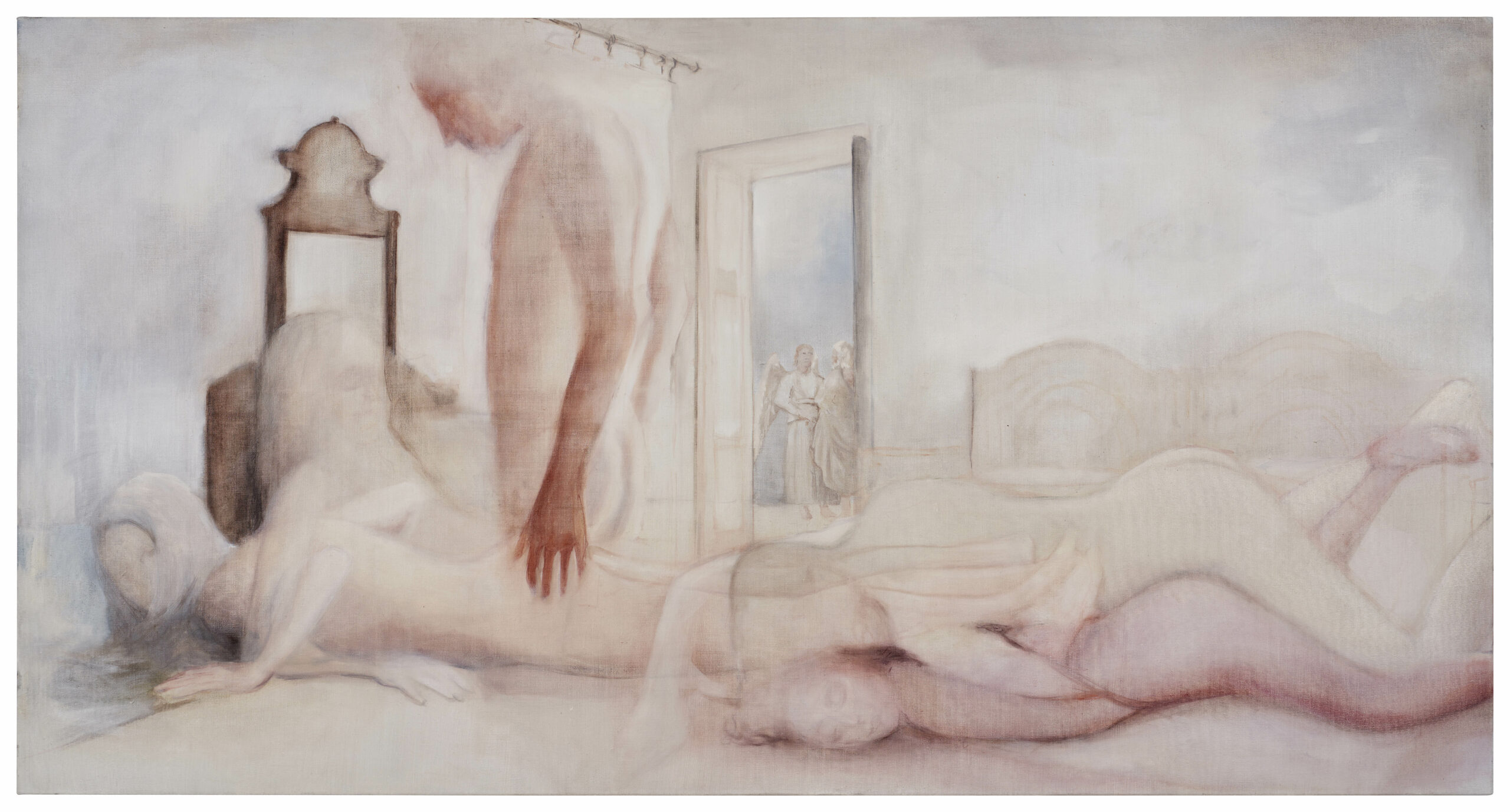

The artist’s new works, previously on display at Wschód, New York, continue depicting these erotic scenes, which– although they are frequently described as dream-like– retain a distinctly nightmarish quality. Upon the wood-tiled walls of the gallery, her canvases become bodies, cut tall and slender or reclining. A nude woman stands atop a stool, arms outstretched beneath a red cape which fades into the ether. She is a Madonna of Mercy with quiet disdain for her task, an unclothed restaging of Piero della Francesca’s Polyptych of the Misericordia (1460-62). Three suited men kneel at her feet, anonymised by their corporate attire and turned backs. They look up with shame, or desire, or both, at Woś’s detached Virgin Mary. Because of, rather than despite, the eroticism of Woś’s practice, her paintings romanticise religion less than they expose its contradictions and obsessions in all of their unbridled violence.

In another work, Courbet’s Young Ladies Beside the Seine (1856-57) reclines underneath a distinctly moody canopy of trees. The women are gazed upon by more men of receding hairlines and untucked shirts and flanked by a spectral figure whose arms are tied in bondage. As the left woman sits up, her sleeping companion is trapped between two worlds, one (or perhaps both) dogged by the interference of male heterosexual desire. Although Woś’s paintings are often raw and even painful in their extremities, they are seductive; it is in this juxtaposition that the artist’s practice is most generous. Layered and fragmented in content as well as form, the work takes on a cinematic quality. As the audience, we become voyeurs.

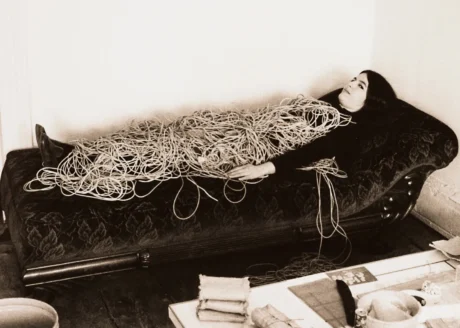

As much as I am struck by the violence which is present in many of these paintings, I am seduced by them; I find them both shocking and sexy. Can depictions of women or sometimes genderless bodies in such states of duress or submission ever be considered liberating? There is an attraction to escapism, like pornography or fetish. Alongside her art historical and religious references, Woś collects material from the internet, such as fetish porn and erotic short stories. What is it which draws us beyond ourselves to the extreme? Both desire and power have never been so straightforward as to be unsubtle; Woś taps into their obscurities without becoming reductive. The malevolent characters she paints are never rendered in as much detail as those who find themselves the subjects of their want. Whether fantasised about or repulsed by, Woś’s erotic scenes are inevitably the emotional territory of the vulnerable.

In the artist’s early work, she painted herself, her own body becoming a vehicle for its fantasies to be realised upon, although her scenes are not, and never have been, as literal as memory or experience. She would depict herself kneeling among ghosts or as a stand-in for the dead body of Christ (as in El Greco’s Holy Trinity (1577-79)). Perhaps Woś’s paintings are easier to digest when her body is positioned so vulnerably by its own admission; perhaps because then we, as viewers, can avoid our own subjectivity in relation to the scene. Now, due to the ambiguities of anonymity (although it should be noted that the artist’s subjects are overwhelmingly, if not entirely, mannequin-thin white women), there is something more disconcerting about her sensual compositions. They take on the perversely disembodied qualities of the pornography she collects or the artificiality of a stock image.

Woś’s practice grapples with the boundary between the profane and the easily swallowed and, in doing so, forms an acutely unbridled portrayal of desire. Although its scenes are pervaded by pleasure and pain (erotic power), they are never lewd. They are the disturbing dream realised, the nightmare which perhaps reveals more about ourselves than we’d like to admit. Although their characters are faceless, at the core of these paintings lies human complexity– and in this complexity, truth. The truth, after all, has never made for easy viewing.

Written by Ella Slater