Central and Eastern European folk art aims to preserve the region’s diverse cultural heritage, chronicling and upholding everyday life through community-based practices such as singing, dancing and costumes. But in areas where right-wing nationalism attempts to monopolise traditions, there is a growing need for feminist interpretations by artists that incorporate folk art into contemporary culture.

The Hungarian and Polish governments have both introduced changes to laws and constitutions in recent years based on so-called Christian and traditional values. This has resulted in curbs to the rights of women for free and accessible abortions in Poland and a ban on same-sex adoption and trans rights in Hungary. By claiming ownership of national values and interests, the dominant right-wing populist parties have forced their political opponents on the left to often shy away from topics concerning tradition, craft and folk art.

In response to this, a growing number of artists are adopting folk traditions and rituals as part of their own creative practice. Their projects offer a feminist perspective when looking at the news media, women’s bodies and peasant culture within a broader question of national identity.

“In folk culture patriarchy is not entirely hegemonic,” says curator Katalin Erdődi. “A few traditions challenge its dominance and serve as outlets for women’s voices”. Erdődi is the creator of News Medley, a collaborative project developed with interdisciplinary artist Alicja Rogalska and folk music advisor Réka Annus. It sees the group pair up with the female choir of the eastern Hungarian town of Kartal to reinterpret traditional folk songs.

The songs have been rewritten to reflect current political themes, as well as to include the personal experiences of the women in the choir. In a political climate where news media is mainly controlled within the country by a right-wing government, News Medley aims to present an alternative bottom-up form of community broadcasting.

“Choir singing is a collective form of self-expression that can embrace a heterogeneity of voices,” says Erdődi. One of the main themes of the folk songs is the invisible labour performed by women when they carry out their domestic duties, which are unpaid and unrecognised. “Woman, woman, she takes care of everything/ And does the housework on top of it,” one song goes. “Oh, if only wages for housework were paid/ I would be a millionaire right away!”

“Looking at them from a feminist point of view can make folk songs into tools of understanding and reflection”

Sirens of Varsány, a feminist choir of young Budapest-based women, has also joined the collaboration. “Folk songs should be interpreted in a historical context taking into account that they were born in a certain sociological time and space,” they argue. “Looking at them from a feminist point of view can make folk songs into tools of understanding and reflection.”

There is more female power in folk art than is commonly acknowledged. While some traditions have been rooted in a patriarchal understanding of the family and work, there remains a strong matriarchal presence in everything from songs to visual art. In the traditional circle dance of the Hungarian Galga River region (to which Kartal belongs), for instance, younger unwed women are encouraged to come together through a vernacular form of communion.

According to tradition, these women share their concerns and fears with one another about the upcoming changes in their lives, the marriage that awaits them and any family difficulties. They dance in a closed form, “creating a safe space in which these private and intimate thoughts can be shared” adds Erdődi.

“I turn towards the archaic to find a way out of the crisis of the present”

Polish painter and visual artist Noemi Conan agrees that folk art and peasant culture are often misrepresented in the region. “I think that peasant culture has strong revolutionary potential,” she says. “These are stories told by the underclass about dealing with a hostile world that looks down on the poor and weak.”

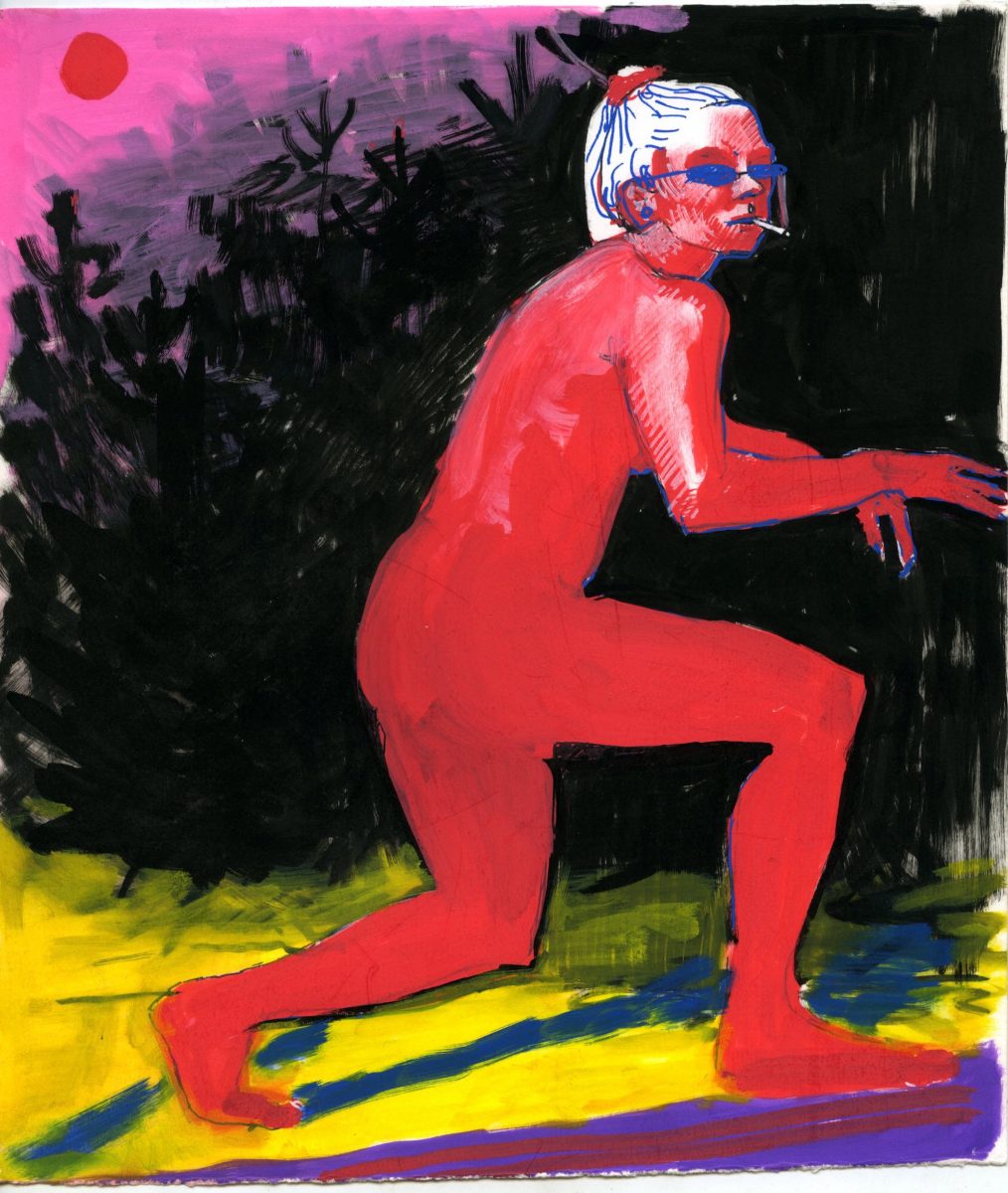

In her work Precarious-The Ladyboss Series, Conan portrays female figures based on Polish mythology and folk tales, in combination with more contemporary references drawn directly from life. In colourful paintings of women who look defiantly outwards, Conan imagines a series of confident characters who drag on their cigarettes, lean on one fishnet-stockinged knee and peek over their cat-eye sunglasses. At once glamorous and compromised, they are shown stealing a moment for themselves in an otherwise thankless landscape of long working hours and little reward.

After the fall of communism in Poland in 1989, she explains, many women found themselves newly unemployed and were forced to resort to sex work in order to stay afloat. As a small child growing up in Catholic Poland, these so-called women of the woods were presented to Conan as “Rusalkas, dangerous female spirits who lead men and children astray, tickle them to death or at least confuse them with riddles”.

“The ladies of the woods, the roadside interlopers, have become a source of inspiration for my paintings. They are confusing, attacking and showing all kinds of unseemly attitudes,” Conan says. “Since the negative or questionable aspects of the fall of communism still upset many in post-communist Poland, I wanted to talk about it through deadpan fairytales.”

“One of the main themes of the folk songs is the invisible labour performed by women when they carry out their domestic duties”

She also disapproves of the way right-wing politics attempts to appropriate folk art. “Conservatives have a tendency to crave a ‘return’ to a past that never actually existed, and I think it is the role of the artist to elevate all the aspects of the past that don’t fit the perfect picture of a white, straight, patriarchal and homogenous people,” Conan continues. “Folk culture also opens up a rich vocabulary of references that expand beyond the now dominant Western view of things, which are easier to relate to and deal with than what comes from further away.”

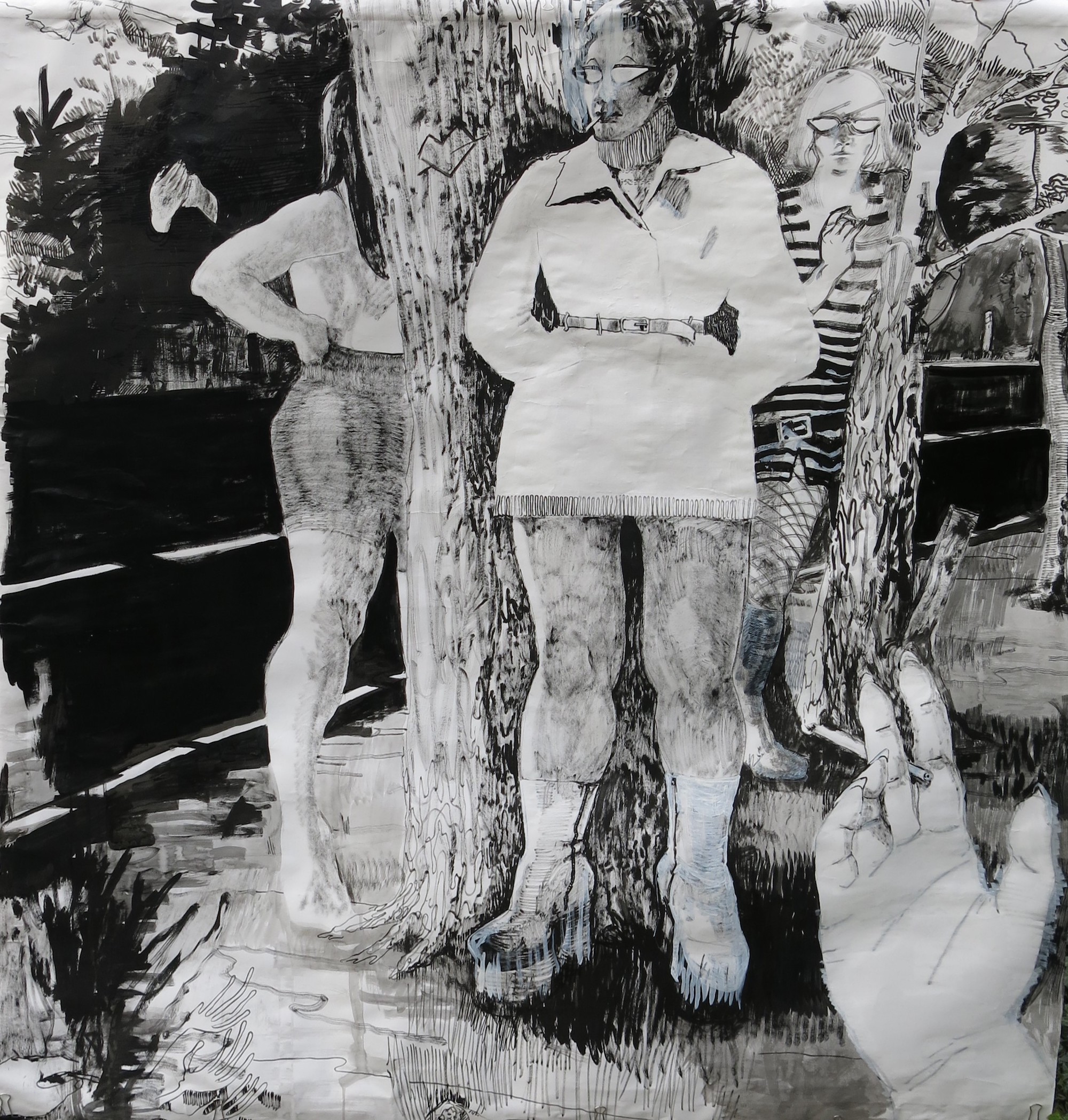

Dominika Trapp, Don’t Lay Him on Me…(install), 2020

Young Hungarian artist Dominika Trapp extends this perspective through her research into peasant culture and the Hungarian dance house movement in light of contemporary feminist thought. Trapp’s 2020 installation, Don’t Lay Him on Me…, focused on the “narrow segment of Hungarian ethnography that dealt with women’s autobiographies. Because of their brutal honesty, these confessional texts stand out from traditional folk narratives, which are generally aligned with the conventional conception of the community.”

“In folk culture patriarchy is not entirely hegemonic. A few traditions serve as outlets for women’s voices”

Trapp’s installation is an ode to the archaic female body as seen in folk culture through tropes such as the ‘folk dancer’ or the ‘peasant woman’, and offers up a critique of its appropriation and misrepresentation. “Relying in part on these sources, I examine the opportunity for manoeuvre provided by tradition in relation to the past, present, and future,” she explains.

Trapp examines peasant culture from a feminist viewpoint, looking at women’s lives via their own storytelling rather than through the male gaze. The main piece of the installation is a curved wooden instrument, a tool for sharing folk anecdotes and a shape suggestive of women’s bodies and their objectification in contemporary culture. “I turn towards the archaic,” Trapp says, “to find a way out of the crisis of the present.”

By taking a political stand, these artists are proving that the rich and diverse folk culture of Central and Eastern Europe still has a place in the present, and not only as a tool for right-wing propaganda. From feminist analysis to post-imperialist reinterpretations of, they offer new context for these ancient art forms. Beyond simply preserving this cultural heritage, they demonstrate that folk art will not only endure but continue to evolve and adapt long into the future.

Noémi Martini is a freelance arts and culture writer focusing on Eastern Europe