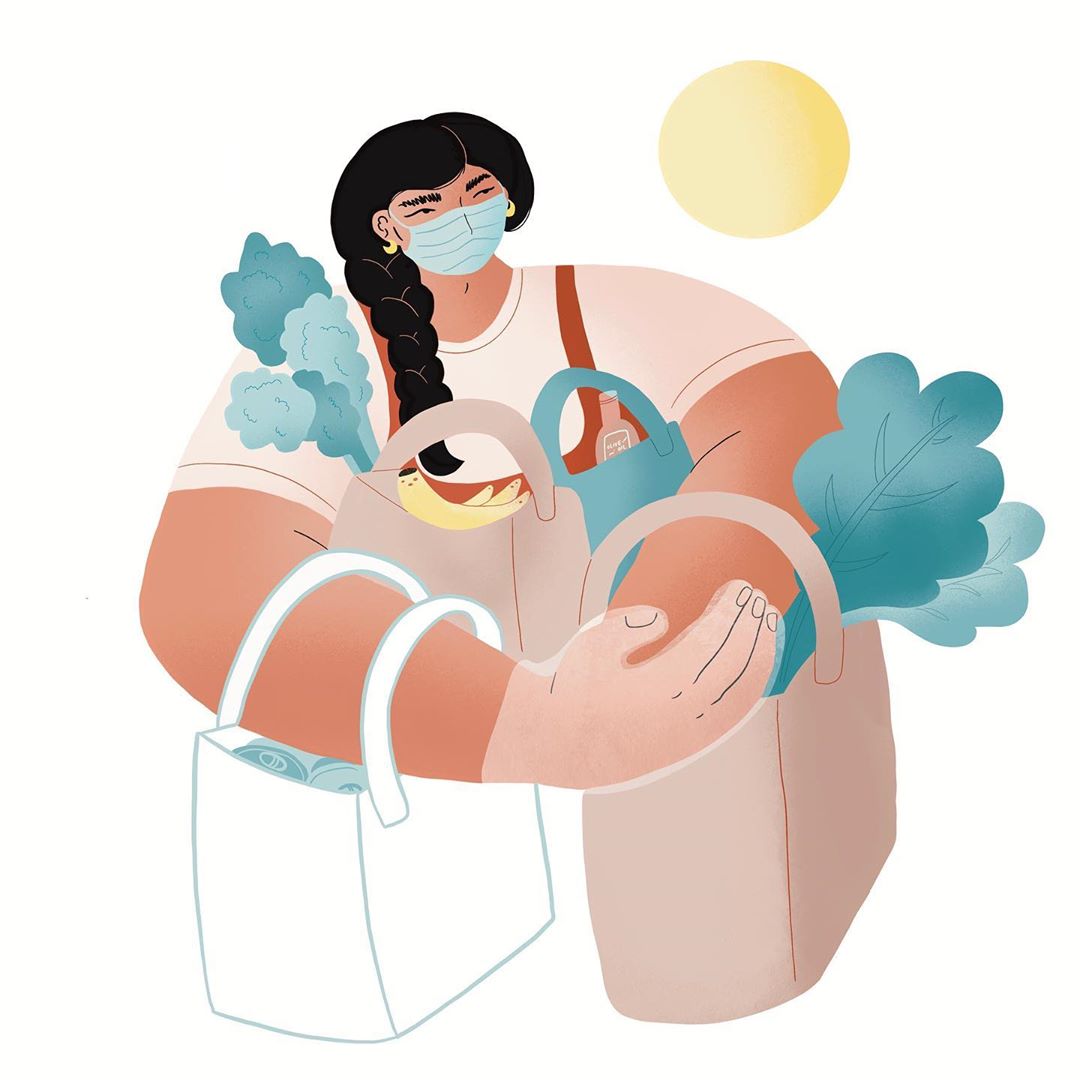

Throughout history, illustration has been used as a mechanism to tell stories. From the earliest recorded cave paintings in 15,000 BC to the explosion of digital art, it represents a deep-rooted yet rapidly changing industry. But now, it has more pertinence than ever. Apt for it’s ease of conveying a particular message, as well as its ability to educate and agitate the status quo, activism has come to the fore in recent months, taking the form of banners, posters, printed material, street and digital art, to name a few. So as the battle with the double pandemic of Covid-19 and institutional racism continues, in what ways can illustration be used to spread social consciousness, to inform and to actively steer change?

Edel Rodriguez is a Cuban American artist and illustrator, whose work traverses disciplines from painting, illustration, sculpture and design. Despite an undoubtedly multifaceted practice, there is one commonality that runs throughout his work: activism. “With all the different visual and sound distractions around us nowadays, a quiet and graphically direct image has a lasting impact. Illustrations can be read and understood rather quickly,” he explains of his reasons for using illustration for social change. “It may take half an hour to read a long-form essay, whereas an illustration can be read in a few seconds; I want the image to be the entry point to that long-form essay, something that grabs you and makes you want to learn more.”

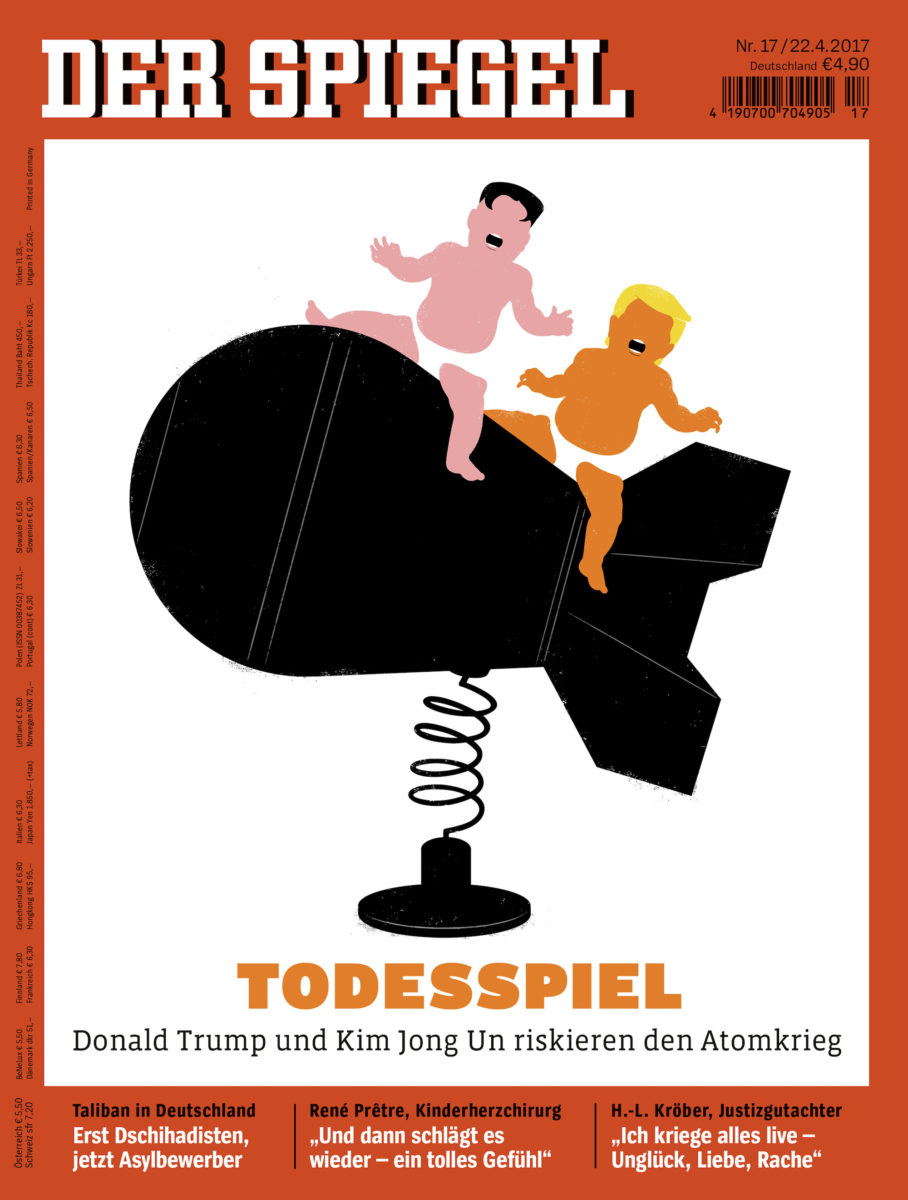

- © Edel Rodriguez

“With all the different visual and sound distractions around us nowadays, a quiet and graphically direct image has a lasting impact”

Illustration has fascinated Rodriguez since childhood. Inspiration came in many forms, and the work of eighteenth century Spanish artist Francisco Goya, World War II posters, the Civil Rights Movement, AIDS posters and Time magazine covers of the 1980s were key players in his decision to engage in activism through art. Before working freelance, Rodriguez was an art director for Time magazine for 13 years, and was the youngest art director to have ever worked on its Canadian and Latin American outposts. It was during this period that his illustrative practice developed, resulting in multiple illustrated covers; rapidly shared online, and pasted on protest banners at real life marches, these covers quickly became iconic. This includes the KKK Time cover, alongside the image of Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un (as children) riding on a bucking bomb, and the image of Trump beheading the Statue of Liberty, both for Der Spiegel.

Over the course of his career, Rodriguez’s politically charged works have been published widely in The New Yorker, Time, Rolling Stone

and Fortune. As such, he has witnessed the landscape change dramatically. “One of the most important things that has happened over the last decade is that, as illustrators, we can become our own publishers,” he says, referring to the internet as the catalyst for reaching a wider and more inclusive audience. Without the changes of editors and publishers, artists have the freedom to “push things a bit further” into the culture. This works twofold, as once the publications see this uncensored work and its potential to reach a strong audience, they too are willing to publish it. “It’s an interesting shift; the viral quality of the internet has helped artists’ original voices get more attention.”

While Rodriguez refers to the digital libration of the medium, Brian Rea sees it as divisive. The American illustrator and previous art director at the New York Times has long thought of illustration as a powerful, and in some cases dangerous, means of communication. But in today’s society, where there are endless tools with which to deliver your message, there has never been a greater focus on exactly how you use your voice. “Then, most importantly, you have to ask: what action are you hoping to achieve? Do you want people to think differently, change their behaviour, act up or burn the whole machine to the ground?”

Over time, illustration has appeared on the street, on the covers of magazines, in videos, animations, murals and, of course, through social media—whether that’s in form of posters and signage from memorials, rallies or protests. But, as Rea puts it: “I don’t think illustration necessarily has more power over, or is more effective than, other messaging approaches (video, lettering, signal and murals), and that may seem strange coming from an illustrator. But if I’m being truthful, some of the most powerful imagery and messaging I’ve seen has been through live video, photography or hand-lettered signs,” he adds, noting their effectiveness in the women’s marches and black lives matter protests, as well as the New York Times written listing of 1000 people who had died as the US surpassed 100,000 deaths from Covid-19.

“You have to ask: what action are you hoping to achieve? Do you want people to think differently or burn the whole machine to the ground?”

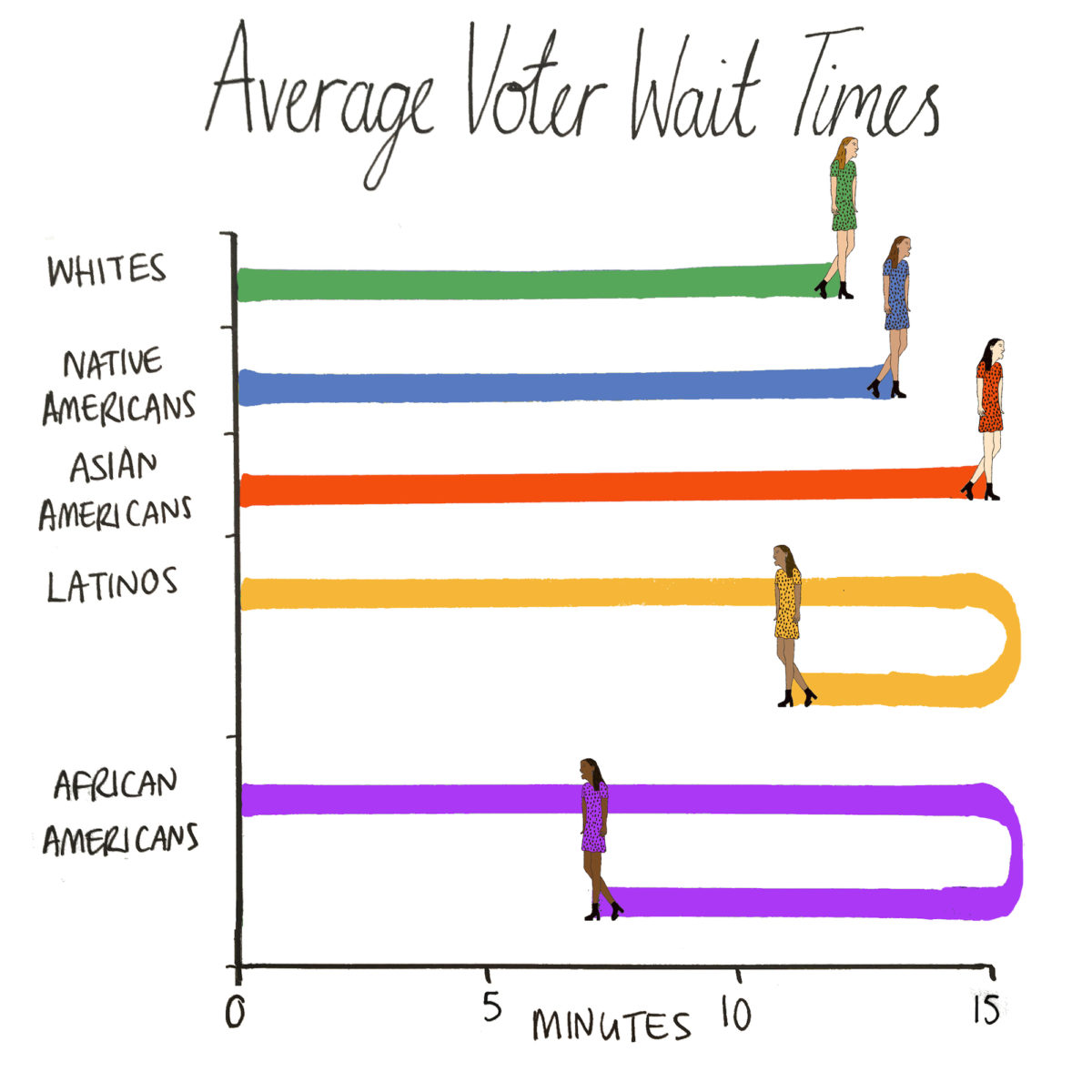

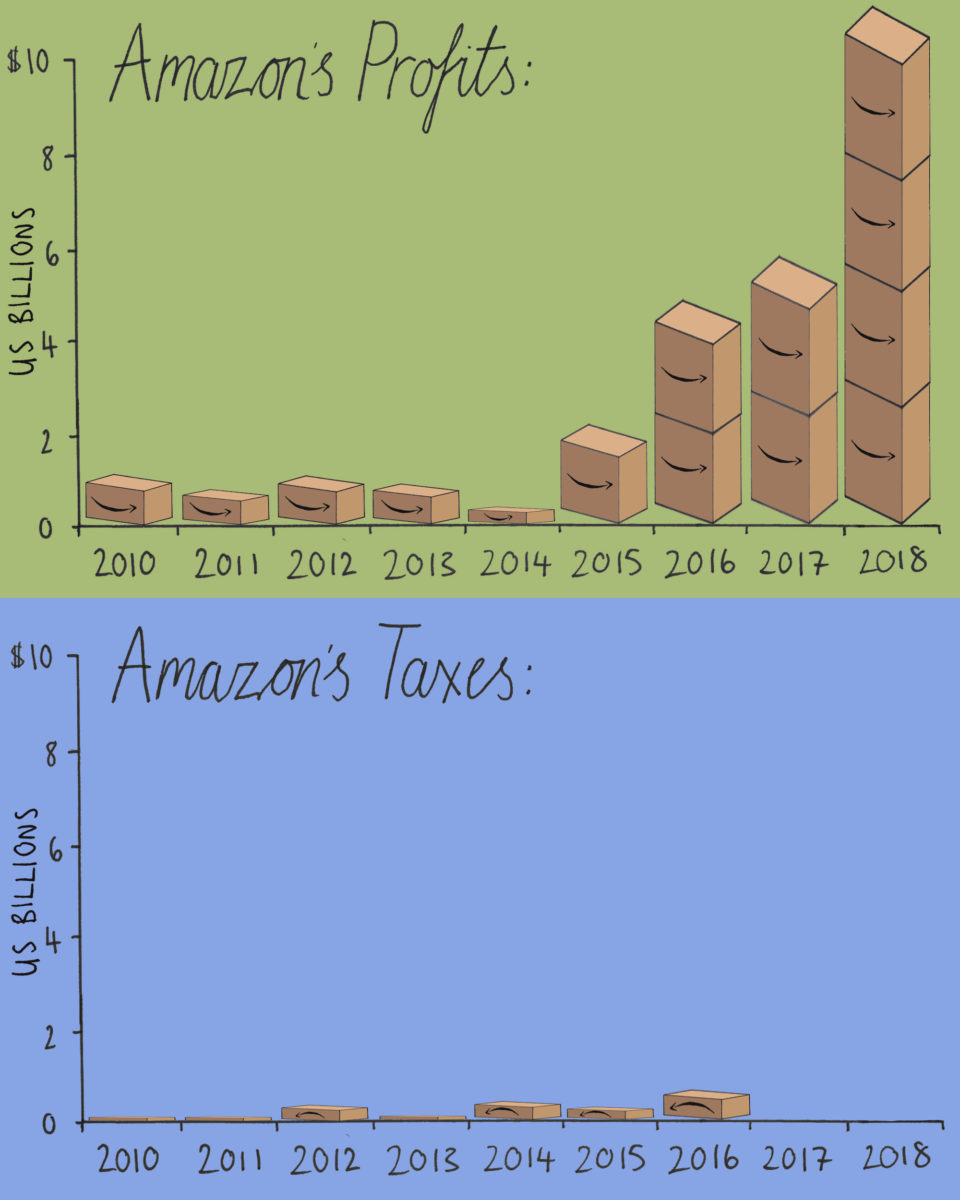

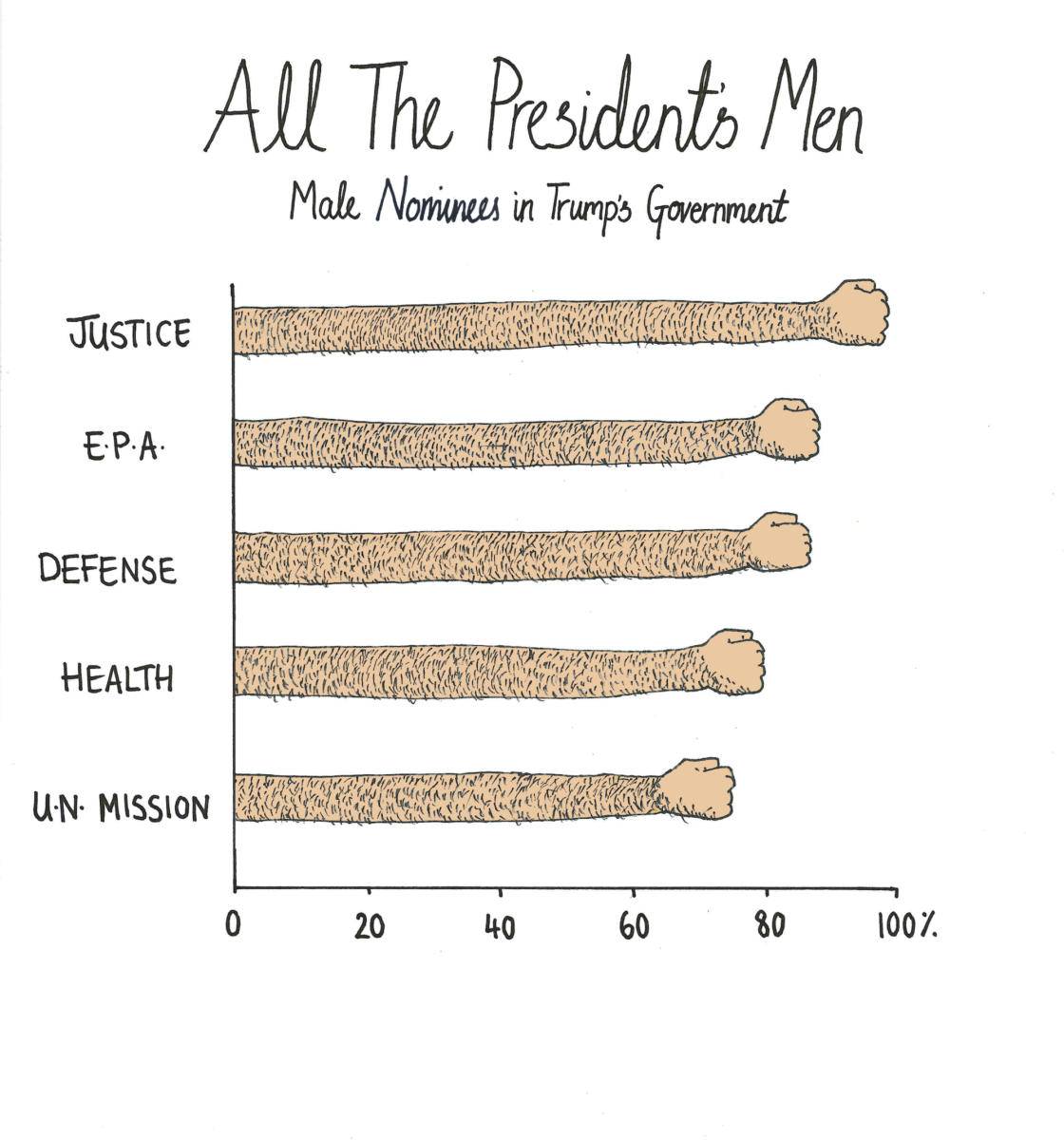

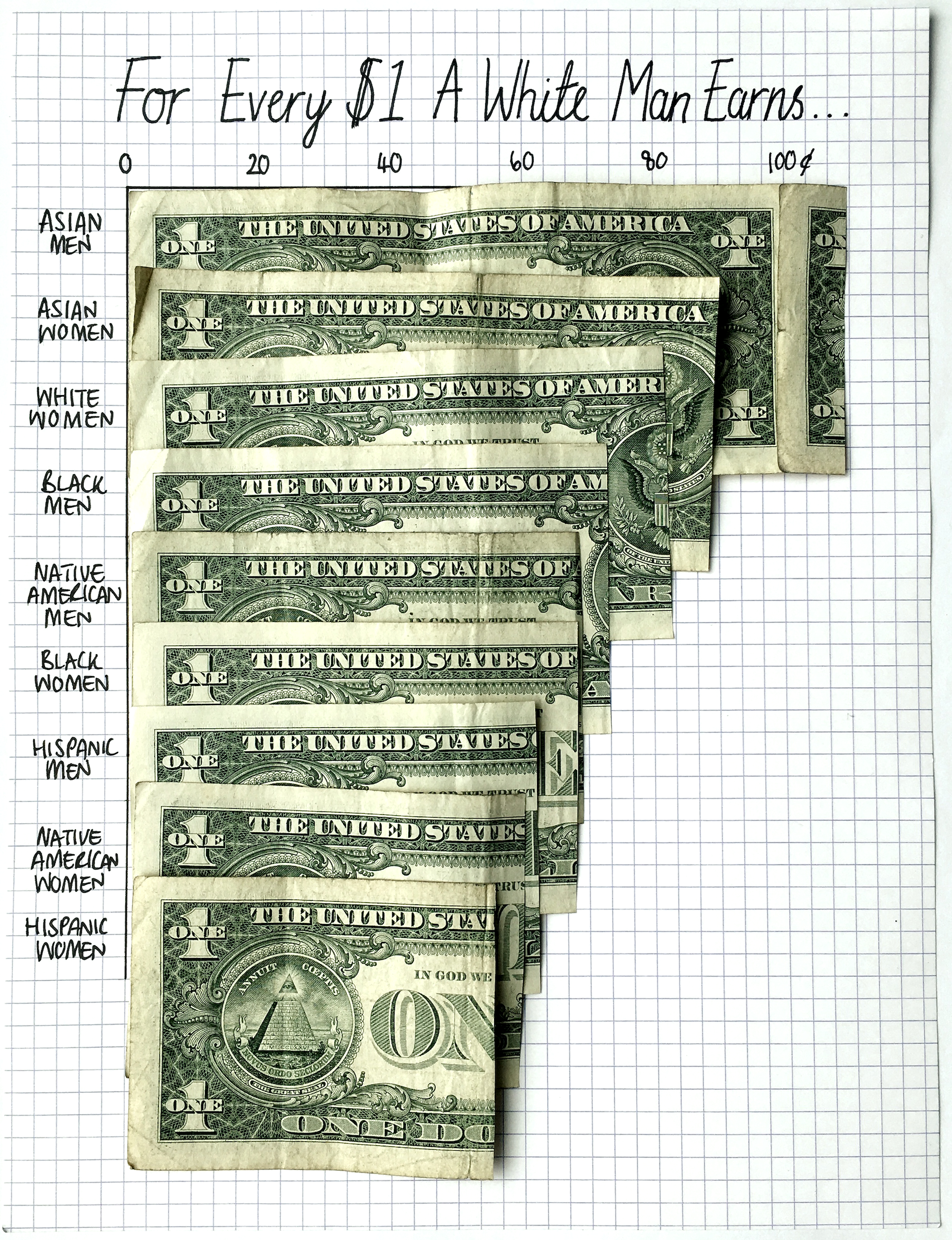

Comparatively, this multi-tooled approach lends itself greatly to Mona Chalabi’s practice, a British data journalist residing in New York who focuses much of her work on post-truth politics. Making a case for how illustration can be a critical tool for activism, she says, “Charts can provide crucial information about injustice, but I think they can hide behind the veneer of objectivity while they’re delivering information.” In this sense, the subjectivity of art opens a window to human empathy that might not have been achieved through the solo and illicit display of words and numbers.

Much of Chalabi’s work has garnered great attention over the recent months, with her colour-inflected graphs and bars visualising facts on Covid-19 and in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. An activist with purpose, her data-centred illustrations are undeniably direct and accessible. “I’m trying to do things differently,” she adds. “I want you to feel something when you look at my illustrations that show data about inequality, racism and abuse of power. Maybe you’ll feel angry but above all, I hope you feel compelled to do something.”

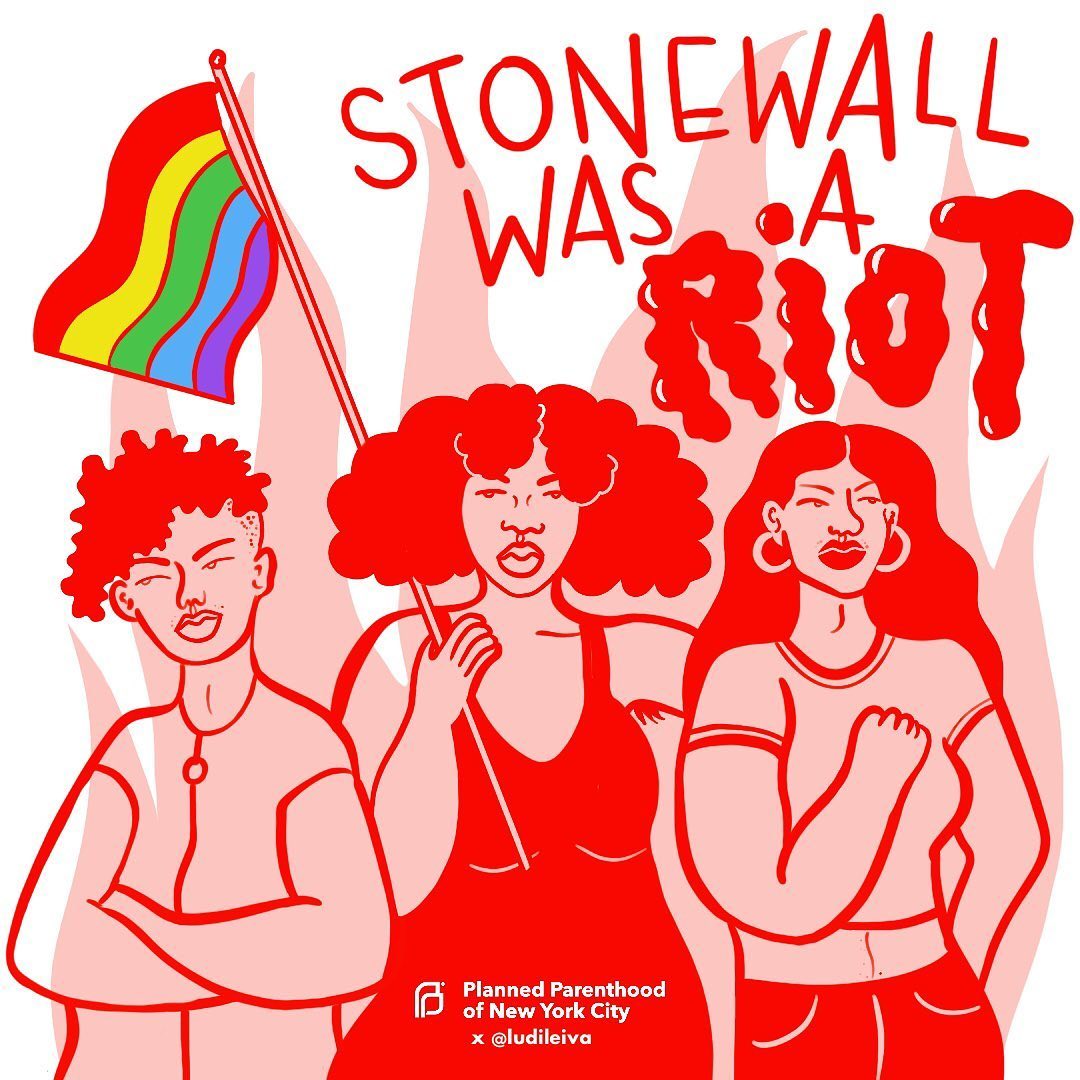

- © Ludi Leiva

Guatemalan-Slovak illustrator and multidisciplinary artist Ludi Leiva also advocates for the power of visual storytelling. As visual beings, she views illustration as a necessary and emotive one: “The common thread between my work, regardless of the medium, is my belief in the power of storytelling for creating empathy, solidarity and making the world a more equal place.” In this sense, illustration goes hand in hand with activism, and is only heightened by humanity’s dependency on storytelling. “Illustrations can help us to tell important stories, make sense of things and feel connected to ideas or other people. Visual art can be a really crucial conduit for positive change and growth, both individually and collectively.”

This is precisely why Leiva has found herself increasingly gravitating towards visual art, following a career in freelance journalism. While it’s never been more accessible to reach a wider audience through the internet, she argues that with this accessibility comes greater responsibility. “To me, it’s important to be walking the walk and not just talking the talk; there can be a lot of virtue signalling, especially right now, and so I think it’s important for artists to consider how they can be having the most positive impact,” says Leiva. This means acknowledging when it’s time to step back or make your voice heard, and thinking about how you can take it further rather than simply creating graphics or illustrations (or posting a black square, as a recent example). Otherwise, there’s also the caution of creating something “embarrassingly obvious or tone deaf”, agrees Rea, which can spur on negative consequences and backlash in the digital sphere.

“Visual art can be a really crucial conduit for positive change and growth, both individually and collectively”

So how can illustrators responsibly use their platforms to steer change? And should they? “I don’t like the word ‘responsibility’,” Rodriguez points out, “it seems to be something that is imposed on someone.” Having grown up in a Communist country where artists were forced to create propaganda for the government and “be ‘responsible’ to the ideology or the people”, this means that he does not subscribe to this specific term. “Every artist should feel the need to share their ideas. They should use their voice to express themselves, however that may be, the same way a writer or a singer does.” It’s precisely this political dominance, subjectivity and inherent personalisation of the medium that makes illustration and activism so complex.

Broad and interchangeable, it really is up to the individual and goal at hand. “Art is a reflection of culture and society,” says Rodriguez, “and there isn’t one way to express all of that. Being irresponsible can be its own form of expression.” However, this puts added pressure on fact checking and keeping work “sharp and direct”, all the while making the image universal and easily understood by a variety of cultures and backgrounds. Rodriguez adds on the matter: “I think that’s the key to a strong image; sometimes one has to put aside more personal and abstract ideas to make something that is widely understood.”

Otherwise, an illustrator’s prerogative is very much centred on being authentic and humble, “and this honestly goes for any person, not just illustrators,” says Leiva. “There’s a lot of ego on the internet and especially social media.” With some users counting engagement and followers in order to clarify their success, this shouldn’t be the “north star” of anyone’s activism, even if a large following does equate to an increased impact and reach. “But in today’s violent, explosive society,” Rea concludes on the matter, “there are monsters who will do anything in their power to wipe out pictures or words that they disagree with. And that is perhaps the biggest reason to keep making strong work.”