During the pandemic, the art world has become more digitally involved than ever. From the growth of NFTs, to online viewing rooms and remote art fairs, the past few years have seen technologically-forward art start to shine.

It’s no surprise, then, that artists at this year’s Venice Biennale have drawn on this too. The international Biennale exhibition, The Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani, places an emphasis on conceptions of humanity in a hostile world, bodily metamorphosis, and more-than-human connections. Across the city, digitally-influenced works were on show, from Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s Maintenancer, to Charlotte Johannesson’s pixel-art weavings.

Just outside the Giardini, Ai-DA became the only robot to date to exhibit at the Venice Biennale, while Cameroon exhibited the first ever Biennale show of NFTs for their national pavilion.

As artists transport us to new immersive worlds and critique the dark corners of the present moment, we select the best works in the national pavilions inspired by, and using, cutting-edge technology.

Greece

According to Sophocles, when an elderly Oedipus left Thebes in search of a place to be buried, he ended up in Colonus, in an area now known as Nea Zoi (“new life”). Today, this area is home to a Romany community: they moved here from Thebes in the 1980s, yet are still treated as outsiders in contemporary Greece. Amateur actors from this local community play all the roles in Loukia Alavanou’s 15-minute VR remake of Sophocles’s tragedy Oedipus at Colonus.

A 15-minute immersive experience places the viewer directly into the makeshift and uncared-for roads of Nea Zoi. With viewers seated in specially-designed skeletal chairs, the 360-degree film slips between farce (at one point, clip art-style bullets rain down) and emotional appeal, as Oedipus begs the community of Colonus to treat him with respect, despite his outsider status.

Georgia

For I Pity the Garden, named after a poem by the Persian poet Forugh Farrokhzad, artists Mariam Natroshvili and Detu Jincharadze speculate about endings. Focused on ecological crisis, the show’s main star is an interactive VR work that takes the viewer through a ghostly, architectural rendering-style layout of an empty, soulless city, where insects congregate in empty supermarkets and gym equipment stands desolate and unused.

As the work unfolds, the viewer is invited into a poetic, interactive game, with floating keywords hovering in the titular garden full of now-extinct plants. When selected, these words conjure poetic phrases gesturing to the destruction of Earth by human action. Natroshvili and Jincharadze, whose work often focuses on archiving lost information, have also included a generative video piece showing fragments of this abandoned environment, for those less-inclined to wear a heavy headset for the 20-minute piece.

Croatia

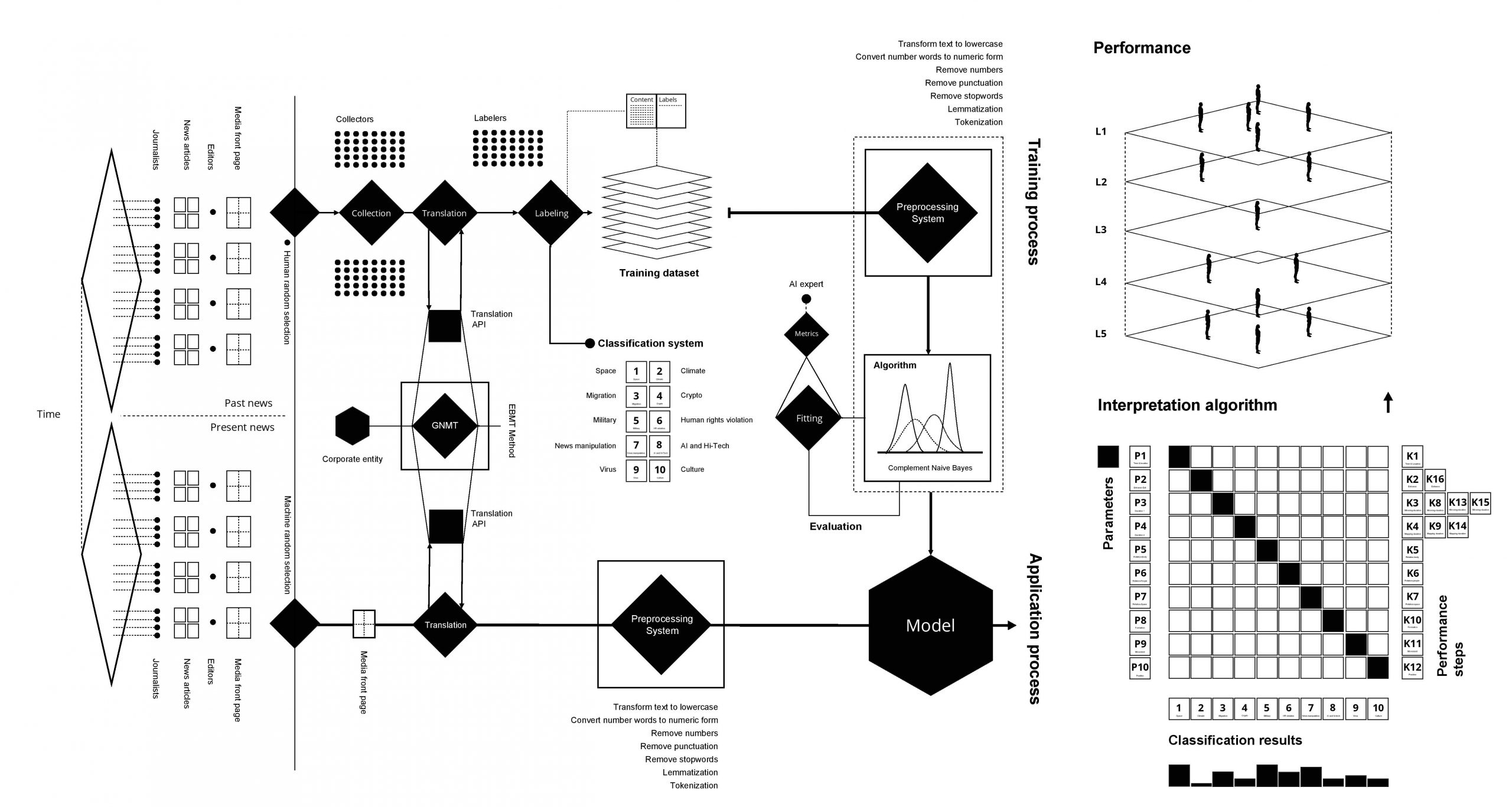

You’ll have to be on top of things to catch Tomo Savić-Gecan’s work. Every day, an algorithm is fed a number of newly-published articles from specific media outlets: it then selects one to analyse and uses it to generate a series of instructions for five performers around Venice. During the preview week, for example, they were spotted at the Finnish pavilion performing a random-seeming, six-minute set of jerky footwork and not-quite-casual leaning on a single foot.

As they’re only generated each morning, make sure to check the pavilion’s website for the day’s performances around the Biennale sites. This blink-and-you’ll-miss-it element is part of the point for Savić-Gecan, who relishes the inconspicuous in his work (in another, untitled work, he covered up a gallery’s walls and painted them white).

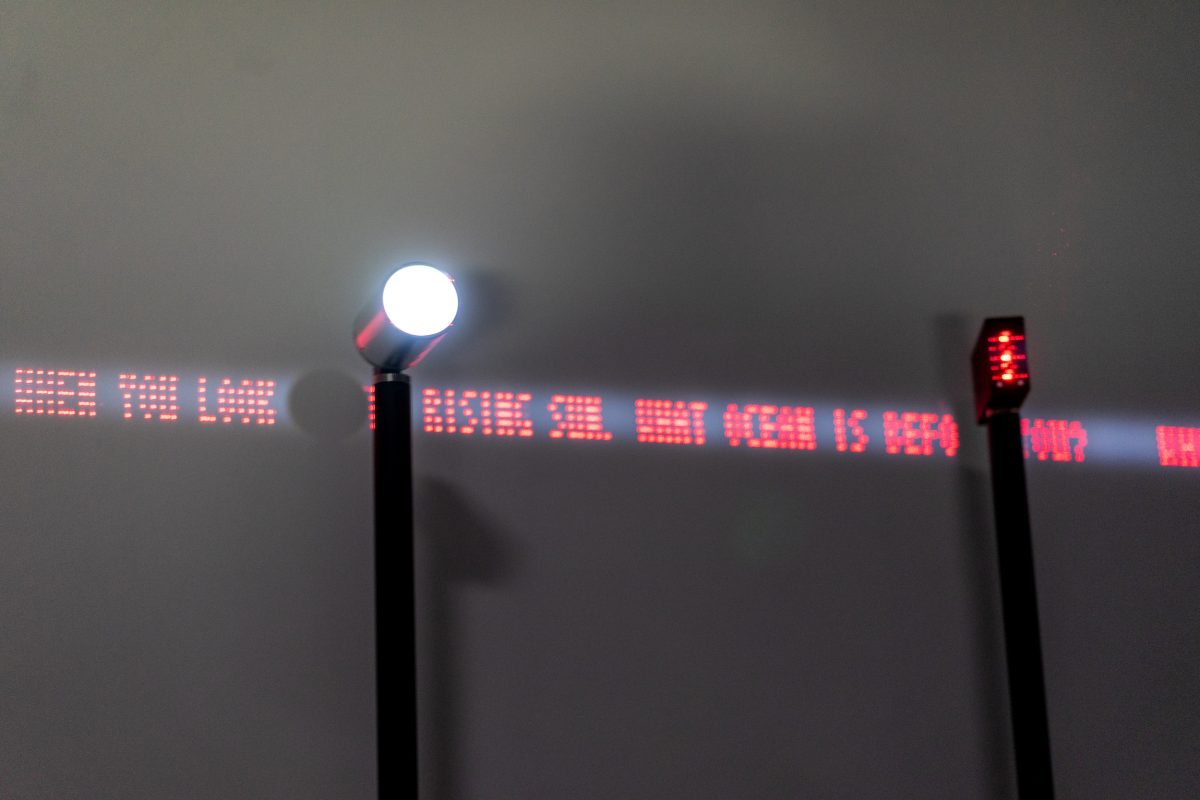

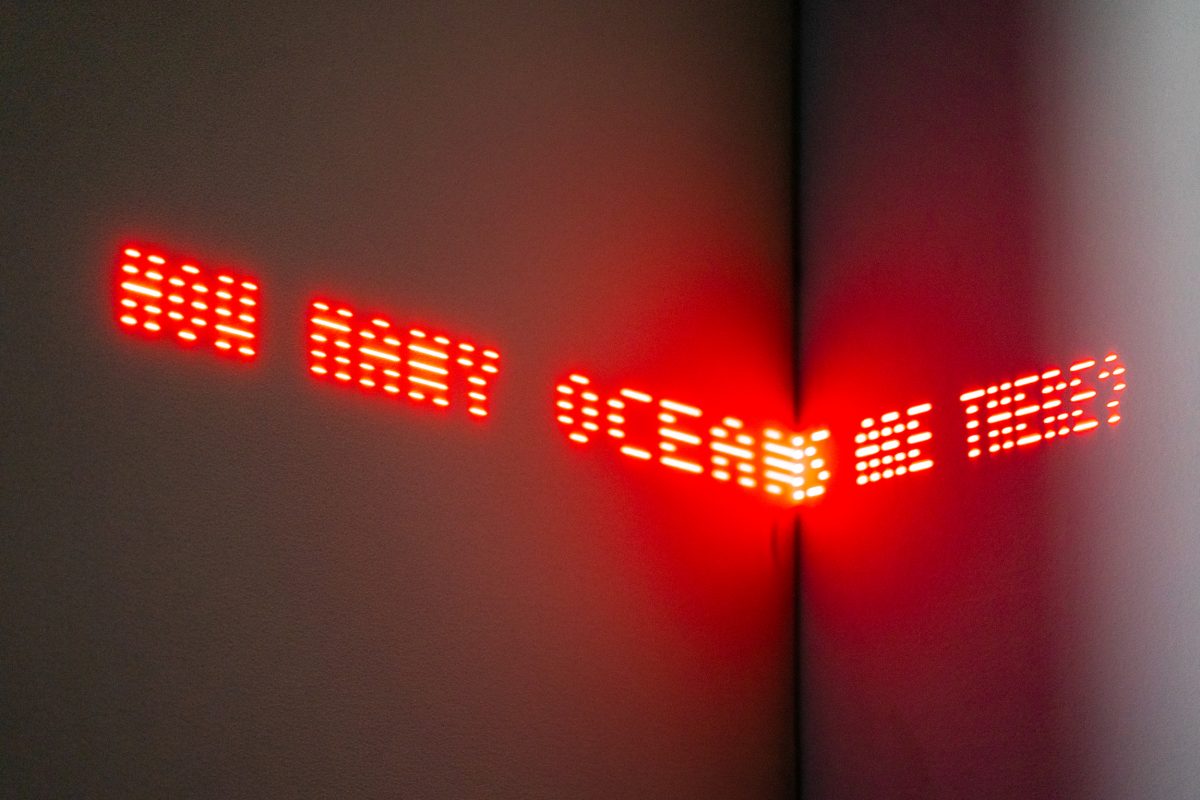

Japan

For their Biennale work, the collective Dumb Type have synthesised our obsession with data into a minimal, buzzing light show of blinking white lines formed by lasers and mirrors. Each represents an out-of-focus line of text, taken from an 1850s geography textbook, the content inscrutable but mesmerising.

The collective (founded in Kyoto in 1984) includes the artists Shiro Takatani and, for this Biennale, the legendary musician Ryuichi Sakamoto (who could be behind the piece’s humming and flickering soundtrack). In the centre of this dark performance space is a square glass hole symbolising perhaps the void at the heart of our Information Age, our ongoing search for meaningful connection.

Romania

Raw, confronting, and vulnerable: Adina Pintilie’s exhibition You Are Another Me—A Cathedral of the Body is not always easy to watch. Her cast of collaborators includes a gay couple, a transgender sex worker and disability activists (some of whom also appeared in her Berlinale-winning feature film Touch Me Not). All appear naked in a nine-channel installation, often touching, embracing, even wrestling as they discuss their relationships to one another in sometimes-painful detail.

A second, harshly blue-lit room contains an oversized robotic arm adorned with smaller screens and mirrors reflecting their contents, like just-opened laptops. At a separate location, Pintilie has produced a VR extension to the project allowing the viewer to touch and even inhabit the viewpoint of her protagonists in a 3D simulated environment, prodding at the boundaries between virtual and tactile bodies.

Uzbekistan

Right at the end of the Arsenale, someone is playing a piano. Or, more accurately, they are playing… something. For French musician Charli Tapp’s sound work Velocity0, a mishmash of algorithms controls a series of electromagnets positioned above the keys of a Yamaha grand piano, each note played at exactly the same resonance, making the composition eerily unemotional.

Each day for the first few weeks of the show, the AI is fed new information in the form of a performance by virtuoso Uzbek instrumentalist Abror Zufarov, who plays traditional music that dates from pre-Islamic culture, which contemporary algorithms trained on the canon of Western music struggle to replicate. It’s fitting then that the work is part of the group show Dixit Algorizmi: The Garden of Knowledge, inspired by the figure of Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī, a 9th-century mathematician born in Khiva (present-day Uzbekistan) whose name is the root of the word “algorithm”.

Korea

It’s easy for our newsfeed-addled brains to forget that, sometimes, technology can be a source of wonder. The Korean Pavilion oozes with works by artist and electronic music pioneer Yunchul Kim featuring pipes and shimmering, luminous surfaces that use automation to create sensory encounters.

It all begins towards the back of the pavilion with Argos‒The Swollen Suns (2022), a towering muon particle detector that uses this information to prompt the exhibition’s other kinetic works. The largest is “Chroma V” (2022), where 382 moveable iPhone-sized laminate pieces form a 50-metre-long installation, like a curved, knotted spine. In another work, air bubbles are blown through medical-looking tubes into shimmering, hexagon-shaped panels filled with a golden, melted mineral liquid.

Josie Thaddeus-Johns writes about art and culture with a tech slant. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts