s 2016 painting of Emmett Till triggered well-documented protests

at the Whitney Biennial. Last year, investors abandoned Robert Lepage’s production Kanata, which was rooted in slave songs. Ariane Grande and Iggy Azalea have both faced backlashes for the cultural influences on their music. In this era of identity politics, the question of appropriation looms large, and with it, the subject of misrepresentation.

British theatre has recently brought the issue to the fore. This was not because of any single incident—though hackles were raised when the National Theatre announced a white playwright, Helen Edmundson, would adapt the late Andrea Levy’s Windrush generation novel for the National Theatre. Instead, the question has spilled from social media and onto the stage itself. Who has the right to tell someone else’s story?

“By squeezing our stories into satisfying shapes, we simplify society and the complex identities within”

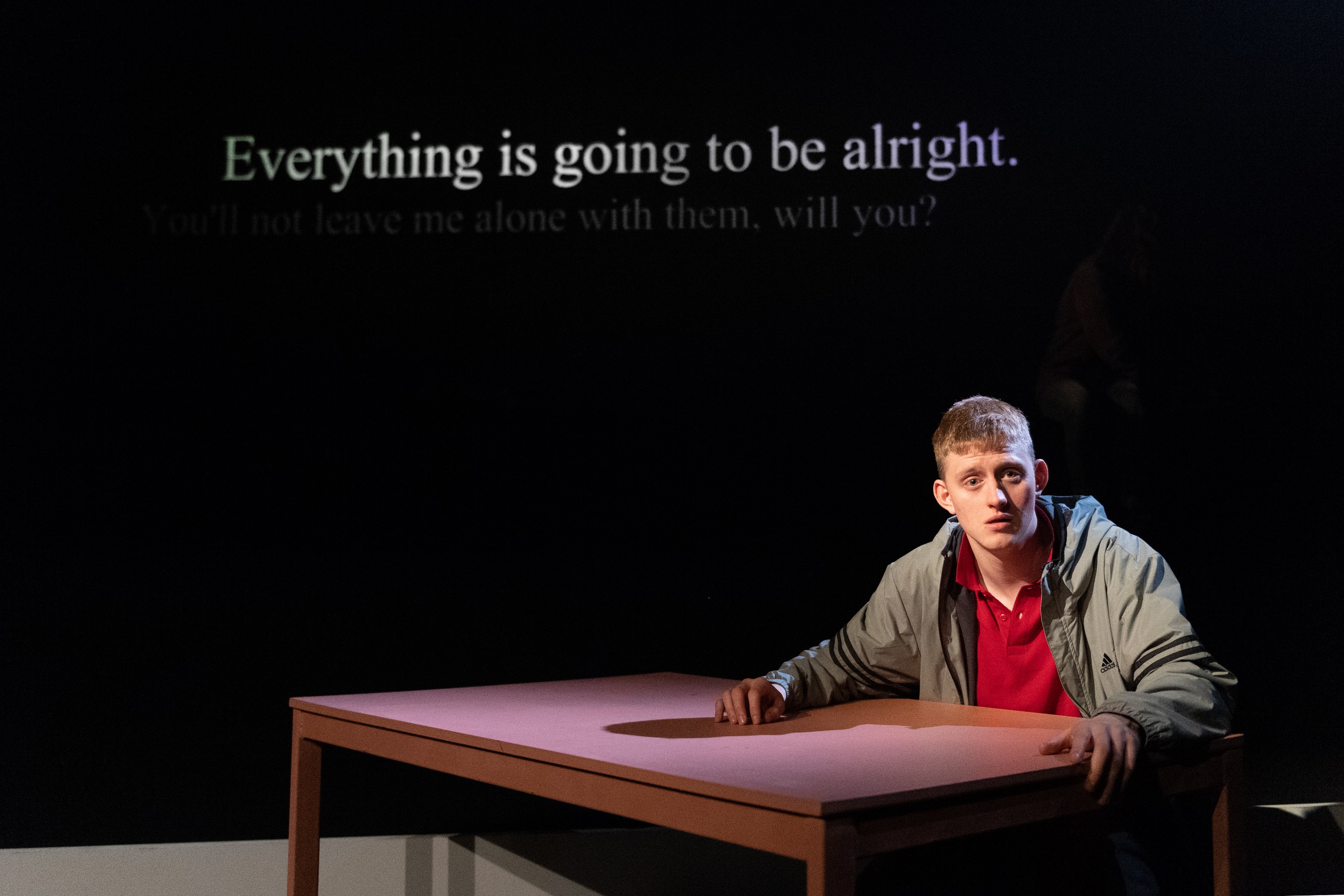

Kieran Hurley’s Mouthpiece, now running at Soho Theatre, examines the ethics and aesthetics of exactly that. In it, a middle-aged, middle class female playwright Libby strikes up a friendship with a working-class teenage boy, Declan. They come from different backgrounds, different generations and different sides of the city, but they share an artistic sensibility. She’s stuck—writer’s block. He sketches for himself. They urge each other on. Her encouragement of him, buying materials he can’t afford and introducing him to galleries he hadn’t heard off, coincides with him inspiring her. His voice feels urgent, so often unheard; his life seems a story worth telling. Is Libby entitled to do so?

Cultural appropriation is complex; always case-by-case, never absolute. When Julian Schnabel argues, as he did in a recent Guardian interview, that anything goes (“My daughter Lola says: Everyone is pink inside.”), it seems horribly simplistic, even sentimental. Ditto Lionel Shriver’s position that an artist’s job involves stepping into other people’s shoes. No foot fits all shoes.

“The question has spilled from social media and onto the stage itself. Who has the right to tell someone else’s story?”

At the other logical extreme, however, artists can only write what they know; autobiography or bust. As the novelist Kamila Shamsie has tweeted

: “‘You—other—are unimaginable’ is a far more problematic attitude than ‘You are imaginable.’” The solution must sit somewhere in between. Shriver’s plea for the possibility of imaginative, empathetic leaps only stands up when coupled with research, respect and rigour. Even that, however, might not be enough.

There are two issues at play in Mouthpiece: appropriation and (mis)representation. Libby’s play is both socially-conscious and self-centred. It seeks to do good, to advocate for change, but it benefits her more than Declan and so, ultimately, solidifies the status quo. It may even exacerbate the distance between them. Declan goes uncredited and uninvited. He can’t even afford a ticket to see the play. “It’s all very well being a voice for the voiceless,” he yells at her, “until you find out the voiceless have a voice.”

Throughout Mouthpiece, Libby puts words in Declan’s mouth and thoughts in his head. She prompts him when he stutters, defines her terms for his benefit and explains artworks he admires. Her play is an act of ventriloquism—she lifts his words, verbatim and not; she takes his title and repurposes it as her own; she imagines reactions on his behalf, projecting herself into his situation. At some point, surely, she oversteps. The question Hurley asks is, Where?

“Tropes become entrenched and, in time, they impact on reality itself”

Libby sits at a microphone, spectacles on, and talks us through story structure: set-up, midpoint, reversal, culmination. It’s a classic arc: what goes up must come down or vice versa. Stories need twists and turns. “There are rules,” she insists, “to make things work.”

Of course, the world doesn’t work like that. It doesn’t conform to the laws of narrative neatness, nor are events limited to seven sorts of story. By squeezing our stories into satisfying shapes, we simplify society and the complex identities within. We distort the world as it really is. Representation is, arguably, misrepresentation. The only way Libby changes Declan’s life is in fiction—for the sake of a good ending.

Stories matter. In shaping the way we perceive the world, they end up shaping the world as it is. Stories evidence our worldviews and underpin our assumptions and, as a result, they inform our decisions and affect our actions. Society is governed by stories. (It might even be a story itself.) If those stories twist the world out of shape like reflections in a fairground mirror, society itself starts to bend and buckle.

Inside Bitch, recently seen at the Royal Court, argues as much. Conceived by playwrights Stacey Gregg and Deborah Pearson, it was devised by four members of Clean Break—all women with experience of the penal system (Lucy Edkin, Jennifer Joseph, TerriAnn Oudjar and Jade Small). Somewhere between a sketch show and a postmodern play, it takes issue with the way prisons are misrepresented in popular culture. The four women pitch a prison drama of their own. “You’ve seen Orange Is the New Black. You’ve seen Locked Up. You’ve seen Bad Girls,” they say. “We’ve got the real shit, and trust me, it’s dark as fuck.”

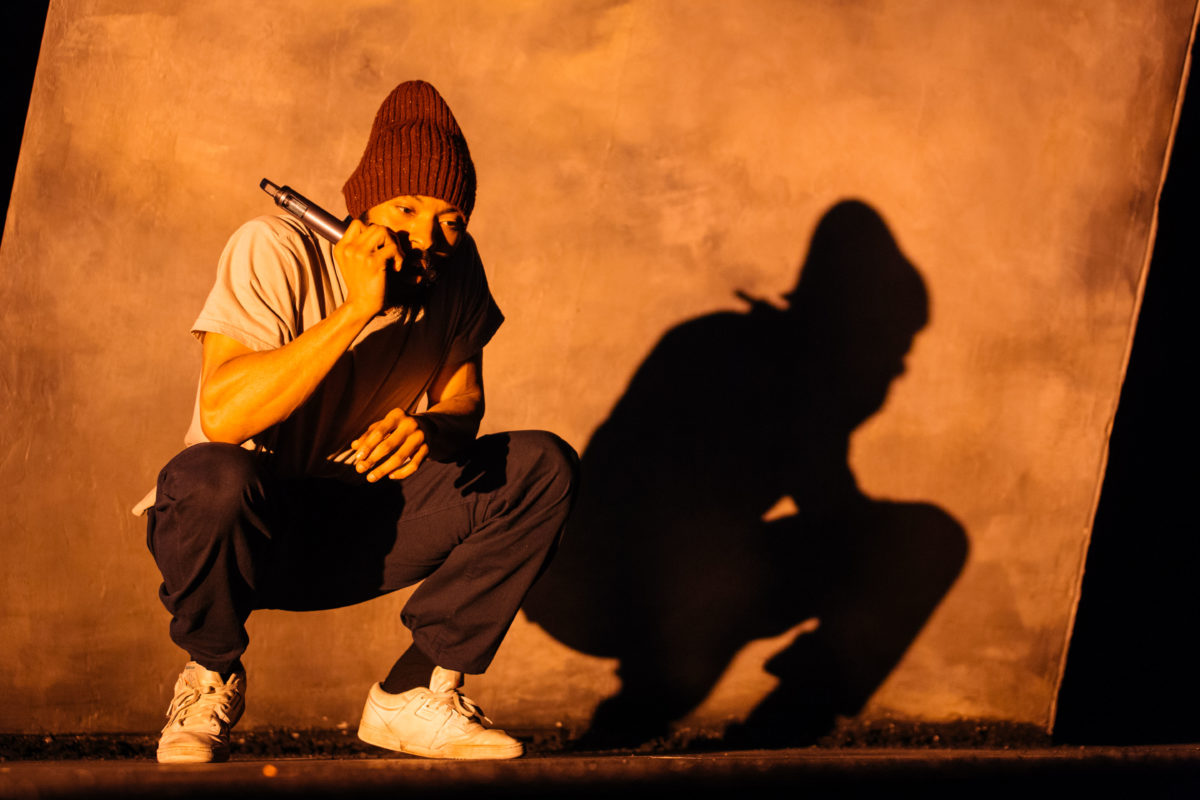

- Arinze Kené in Misty by Arinze Kené at the Bush Theatre © Helen Murray

By their very nature, prisons are places that offer limited access and most of us know them only as they are portrayed—at several removes. For most of us, our idea of them comes almost entirely from cultural representation. That, inevitably, tees up a feedback loop. Tropes become entrenched and, in time, they impact on reality itself. Inside Bitch offers a handbrake corrective. Its artists wrestle back control of the means of representation.

An author’s own misconceptions aren’t solely to blame. Misrepresentation is cyclical: audience expectations inform programming decisions in a risk-averse industry that panders to ticket-buyers tastes. In his meta monologue Misty (which premiered at the Bush Theatre, London in 2018), Arinze Kene reflects on the pressures that pile on black artists. It’s a split narrative: half story, half-storyteller. Kene starts a pulsing spoken word piece about a black teenager on a night bus falling into a fight, only to pull his story up short. What does it mean for him to tell a story like this? An inner-city cliché: “a modern minstrel show”. His (white) agent urges him on: audiences lap this stuff up, theatres commission it.

Misty has a parallel in Ella Hickson’s The Writer, an assault on patriarchal artistic hierarchies. It follows a young female playwright butting up against the tastes of male gatekeepers. When she abandons domestic naturalism to swerve, mid-play, into a freeform feminist fantasy sequence, her director objects outright in the following scene. This is how culture gets curbed; the mainstream self-replicates. The Writer, like Inside Bitch, is a rebellion. It finds its own five-act structure: circular, not causal; echoes, not effects.

“Stories evidence our worldviews and underpin our assumptions and, as a result, they inform our decisions and affect our actions”

In Misty, Kene starts to seize up into self-consciousness. His stories stop being simply stories and become images of blackness, images that impact on the way black men are seen. Instead of speaking, Kene starts burping up orange balloons—a mark of his creativity becoming commodified; the way his words morph into cultural artefacts. At one point, he is himself swallowed whole by a balloon: just a head bobbing out of an orange bauble. His whole person is objectified and he ends up suffocated, unable to speak.

Arinze Kene in Misty by Arinze Kene at the Bush Theatre. Photography by Helen Murray

Hickson’s playwright, by contrast, ends by admitting defeat. She retreats from the patriarchy, from her heterosexual relationship, to cocoon herself up in an all-female, ultra-feminine flat. Out the window, we see the city: the world is unchanged. Where Kene loses his voice, this writer gives hers up. She opts out. Both end up, somehow, silenced, incapable of speaking their story and, in their absence, others might step in.

All these productions share something: they examine the problem of cultural appropriation and misrepresentation without necessarily alighting on a solution. They offer a corrective, but not necessarily a way forward and, until that’s found, misrepresentation will continue to be felt.