Who gets to tell stories and why do we end up listening? This question is posed by Candice Breitz in Love Story—the video work she chose to show at the South African pavilion during the Venice Biennale last year. I saw it a few months earlier at KOW during Berlin’s Gallery Weekend, where I was confronted with the familiar face of Alec Baldwin retelling the life story of a child soldier from Angola in front of a lurid expanse of green screen. I watched the SNL star, as well as Julianne Moore, as they cycled through five further roles, all refugees expelled from their homes due to war, persecution and violence. Between the quick cuts and polished performances, I was rapt.

Afterwards, I headed downstairs to find videos of the original subjects reading their narratives and quickly it became evident that what I had first experienced was a flashy, Hollywood version of the reality these people have lived: Shabeena Francis Saveri, a transgender activist from India who is commanding and scholarly; Sarah Ezzat Mardini, who speaks with a youthful brazenness about her journey from Syria, where she saved twenty people with her Olympic-level swimming. Each talking-head-style interview lasts several hours, making them almost impossible to watch in full. Breitz forces the audience to confront the way we interact with stories about refugees, how they become visible and, most notably, what the filter of celebrity does to that visibility.

“When your labour and your being are criminalized, your human rights evaporate. You have nowhere to go to seek recourse when you are violated”

As Love Story’s narratives are reperformed by well-known celebrities they are made accessible, attention-grabbing and digestible for an audience used to the undemanding nature of GIF responses, Facebook previews and tabloid headlines. In Breitz’s work, however, it is inescapable that the former is an impoverished, abbreviated and flat imitation of the original.

“It was important to me that the disparity in visibility and prominence was reflected by the work, rather than falsely negated by it,” Breitz tells me, as we discuss the piece over coffee. “It’s naive and unproductive to assume that you can automatically get people to sit down and spend time ingesting and reflecting on complex stories that are completely removed from their experience. Especially in an attention economy in which we’re increasingly socialized into a fast-forward relationship with endless streams of information.”

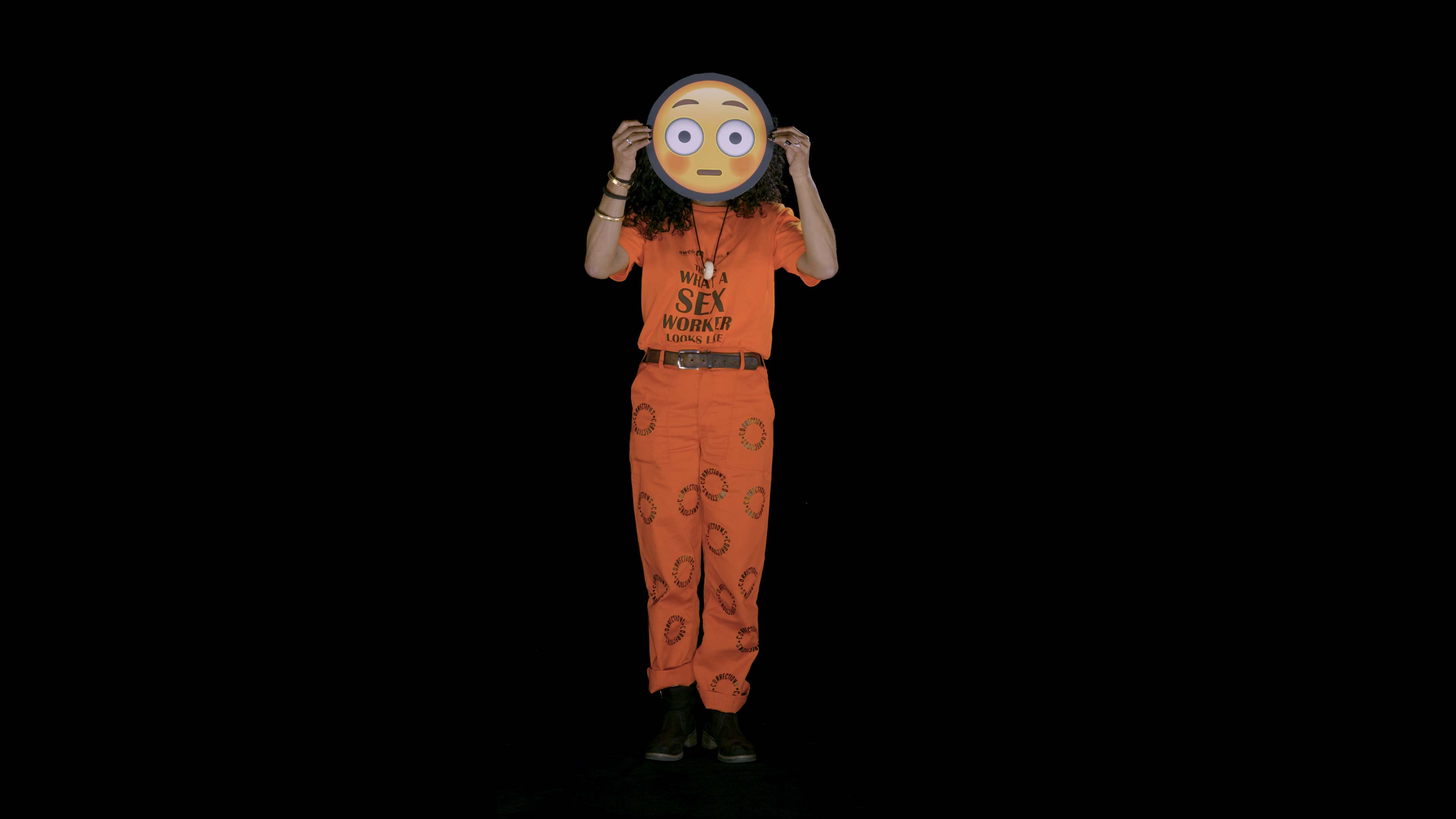

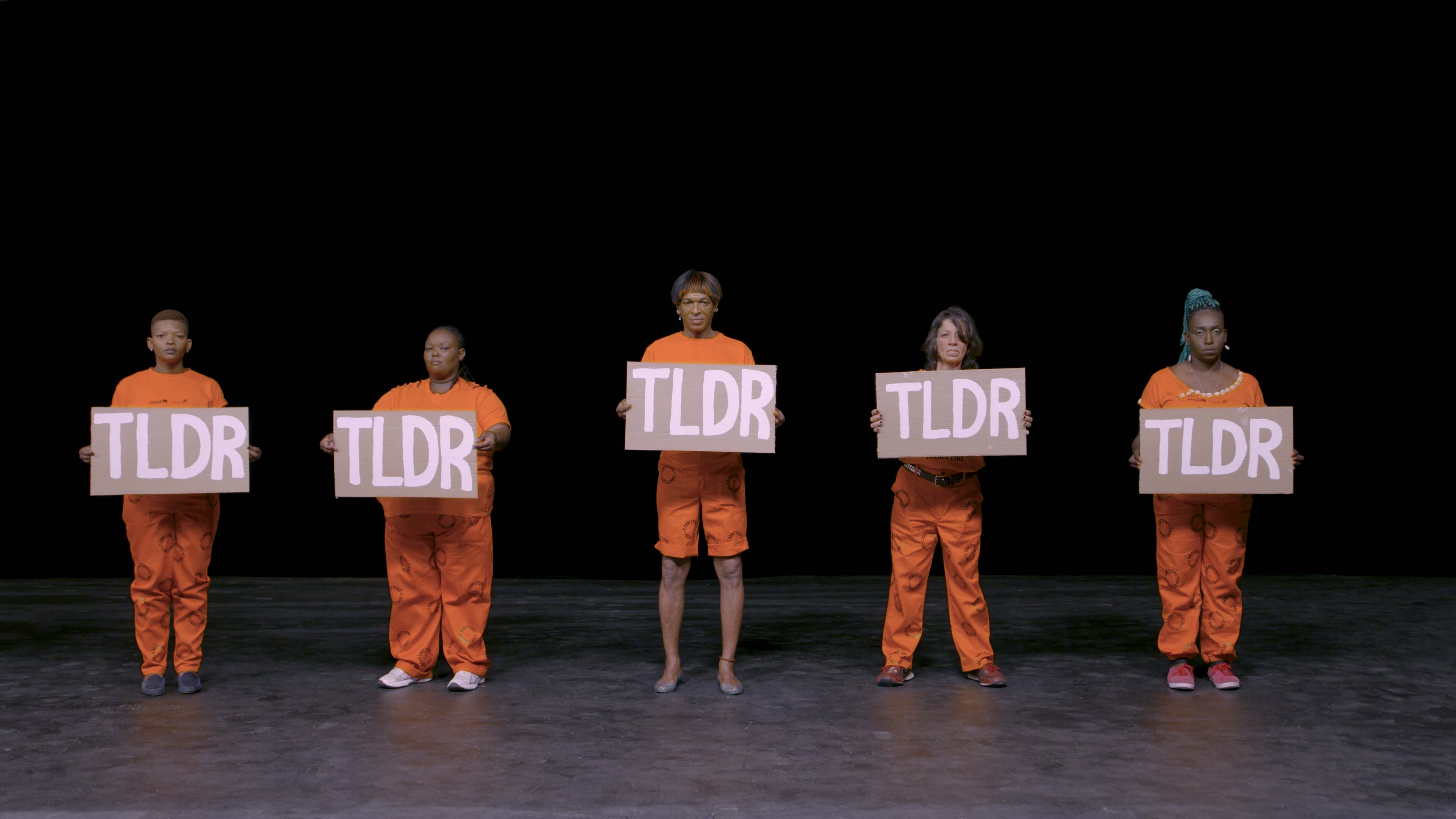

We meet in Frankfurt where she is installing her most recent work, TLDR, commissioned for the B3 Biennial of the Moving Image. TLDR continues where Love Story left off, in its dogged pursuit of attention-grabbing tactics (Breitz calls it “Love Story on acid”). “I used every dirty trick I could come up with,” she says. A collaboration with the South African sex worker advocacy group SWEAT, TLDR also mirrors the setup of her earlier work, with eleven lengthy single-screen interviews and a pacier hour-long film with three channels, delivering a punchy exploration of an issue the group has been campaigning for since the nineties: the decriminalization of sex work. Just like in Love Story, the viewer is drawn into the flashy tactics of the larger film, while the lived particularities of a marginalized group are explored in their own voices on multiple smaller screens.

TLDR’s set piece (the title stands for “Too long; didn’t read”, a perfect acronym for Breitz’s ironic compression of complicated narratives into a snappy film) is made up of three channels. A central panel features a young boy explaining the unlikely but true story of the ideological battle between Amnesty International and a coalition of Hollywood actresses including Lena Dunham and Meryl Streep; while the left and right panels are filled with a line of prison-orange-clad sex workers who act as a kind of Greek chorus to this narrative.

After nearly three years of research, interviewing sex workers and their advocates, Amnesty International announced its new draft policy on sex work recommending decriminalization as the most effective way to ensure sex workers’ rights. Nevertheless, an assortment of Hollywood actresses condemned Amnesty’s work. Their outrage was widely covered, the actresses providing a perfect image to accompany headlines proclaiming them women’s rights champions. “The Amnesty International story became a vehicle to address the brute injustices faced by sex workers in South Africa and beyond,” Breitz tells me, “because the issues and challenges are similar wherever sex work is criminalized. When your labour and your being are criminalized, your human rights evaporate. You have nowhere to go to seek recourse when you are violated. You’re forced into a state of precarity.”

Throughout the piece a dissonance is felt between not just the sex workers, who are principally black, and the predominant whiteness and blondeness of the actresses who claimed to speak on their behalf, but also Breitz herself. “There was no way to make this piece without including a layer of reflection on the violence that is inherent to white privilege, in other words, the violence that is inherent to whiteness,” she explains. “You can’t wash away white privilege. It needs to be constantly addressed and deconstructed. You can try to use it against itself by extending some of the visibility that attaches to whiteness to issues and communities that are generally denied broader visibility. To a large extent TLDR is about how attention tends to land in the wrong places for the wrong reasons. One of the big challenges of the piece is to try to ensure that attention lands in some of the right places for a change.”

Breitz met the work’s young narrator, Xanny, at a public meeting at the South African National Gallery protesting the inclusion of photographer Zwelethu Mthethwa in a high-profile exhibition about the female form. Mthethwa was at that time accused (and has now been convicted) of murdering sex worker Nokuphila Kumalo. “The urgency of the meeting was tangible. People were scrambling for the microphone, fighting to have their voices heard,” Breitz says. “All of a sudden this eleven-year-old kid grabs the mic and proceeds to address the room from a position of profound empathy, drawing on an intersectional understanding that would challenge most grown feminists (of the white variety in particular). The adults in the room were gobsmacked.”

Xanny precociously narrates the film in sassy millennial cadence, with exaggerated facial expressions and cardboard signs daubed with acronyms: “OMG”, “WTF” and “TMI”. “Xanny narrates TLDR from the brink of puberty. He was twelve at the time of the shoot, and very open to the fluidity of gender. It’s important that his presence can’t simply be read as that of a man or an adult,” says Breitz. “For me Xanny represents a different possible future, a future in which men might think and behave differently. In that sense his character is utopian.”

Breitz began filming TLDR the day the Harvey Weinstein story broke. She came onto the set, tore up one of the “bastard” signs that they used as props and added Weinstein’s name to Crosby’s, Polanski’s and Pistorius’s in the lineup. This cultural moment, and particularly the way it came about, could hardly have been better engineered as a backdrop to Breitz’s work, as the media stops and listens to the uncomfortable things that rich, famous, powerful women are saying.

In South Africa, where apartheid’s legacy is still ensuring that many older black women have not had access to education, where the unemployment rate is at forty per cent and extremely low-paid domestic work is the most feasible type of legal work for many women, the structural dynamic of power is particularly stark. “I wanted the specificity of the South African context—as well as the particularity of the individuals who are interviewed in the work—to resonate. That happens in different ways. The central narrative and the interviews are spoken in English, but the repertoire of protest songs that are woven into the work (all drawn from the activist practice of the SWEAT community) are sung predominantly in Xhosa. One of the songs performed in the final scene is South Africa’s post-apartheid national anthem, retooled by the activists to articulate challenges faced by the sex work community.”

The piece is ultimately a collaboration between the SWEAT activists (Zoe Black, Connie, Duduzile Dlamini, Emmah, Gabbi, Regina High, Jenny, Jowi, Buhle Nobuzana, Tenderlove and Nosipho “Provocative” Vidima), and Breitz explains that she chose this specific group as collaborators for a reason: “I was specifically interested in working with and through SWEAT because this is a community with agency, a dignified community consisting of fierce political thinkers. I wanted TLDR to amplify the culture that the SWEAT community has worked so hard to build. I wanted you to understand the hardships that this community faces, but I wanted you to feel the warmth of the group, the humour and strength and resilience of the individuals who belong to it. Because the last thing that this particular community would want is for you to project your pity.”

Much of the presentation of TLDR comes from SWEAT’s own visual language—using hand-painted signs just like they use in their ongoing urban activism, as well as the #SayHerName campaign, where the group holds posters honouring the many sex workers who have died in violent circumstances.

While most of the film was scripted by Breitz with SWEAT’s input, the end of the piece, a joyful singalong of protest songs, is entirely improvised: “The structure of the work broke down and the story gave way to a joyous celebration of community, which was clearly complete without my involvement as a director.”

Breitz is interested in community representation but also in the context of her own subjectivity: “Personally I’ve reached a point of saturation when it comes to privileged artists stepping into marginal communities without any consideration of how their privilege shifts the dynamics of the dialogue with their subject. There has to be a reflection on how privilege is premised on and perpetuates power disparity,” she says. “I believe in the power of a strong story to unsettle its audience and to challenge dominant narratives. That said, telling stories is just one way of responding to injustices, it’s certainly not entirely adequate in itself. In the end, the big question for an artist like myself—privileged, white, middle class—is how and whether one can be an ally, how and whether it might be possible to engage embodied experience without simply interfering from a perspective of entitlement, like the Hollywood actresses in TLDR, self-appointed white saviours who swoop down to rescue ‘the poor prostitutes’, without stopping to wonder whether ‘the poor prostitutes’ actually want or need to be rescued.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 34

BUY ISSUE 34