Scarlett Hooft Graafland, Polar Bear, 2007

Polar Bear is part of a series that the artist worked on while staying in Canada, in the Inuit settlement of Igloolik. There is an unexpectedness to this photograph which is characteristic of all her work, bringing together the awe-inspiring and overwhelmingly vast natural landscape with human intervention. This example in particular is confronting. We’re used to seeing the classic image of the cute polar bear standing on a small block of ice—the over-used visual cliché for global warming. In Hooft Graafland’s image the charcoal-black sky looks almost apocalyptic, and the emptied-out polar bear skin, housing the artist with her bare legs and feet just visible, instinctively calls to mind the wasteful and cruel practice of animal skinning for fashion purposes. Yet this bear skin belongs to a group of people who without doubt make far less of a damaging impact on the world around them than we do in our built-up cities (this particualr skin was rented from an older woman, and at the time there was a quota for the amount of bears which could be shot). All of the confusion I feel when I look at this photograph sums up so much of our relationship with animals and the natural world, where some things are cordoned off and others seen as fair game.

Image © Scarlett Hooft Graafland, courtesy Flowers Gallery London and New York

—Emily Steer, editor

Walter De Maria, The New York Earth Room, 1977

In Walter De Maria’s The New York Earth Room, 200 cubic metres of soil occupy a space measuring 335 square meters, above busy Wooster Street in New York’s SoHo. Installed by the radical, reclusive American pioneer of land art on his forty-second birthday, it was intended as a temporary exhibition. Challenging the very make-up of an artwork, it is stripped back to a material that is both elemental and teeming with life—mushrooms occasionally grow on it, and the same caretaker has tended the installation since the late 1980s. It has remained in place for more than three decades, a meditative, minimal intervention that becomes increasingly incongruous as the city transforms around it. The Earth Room remains a constant, unchanging presence—an important reminder of the natural world that is at risk of slipping away entirely.

—Louise Benson, deputy editor

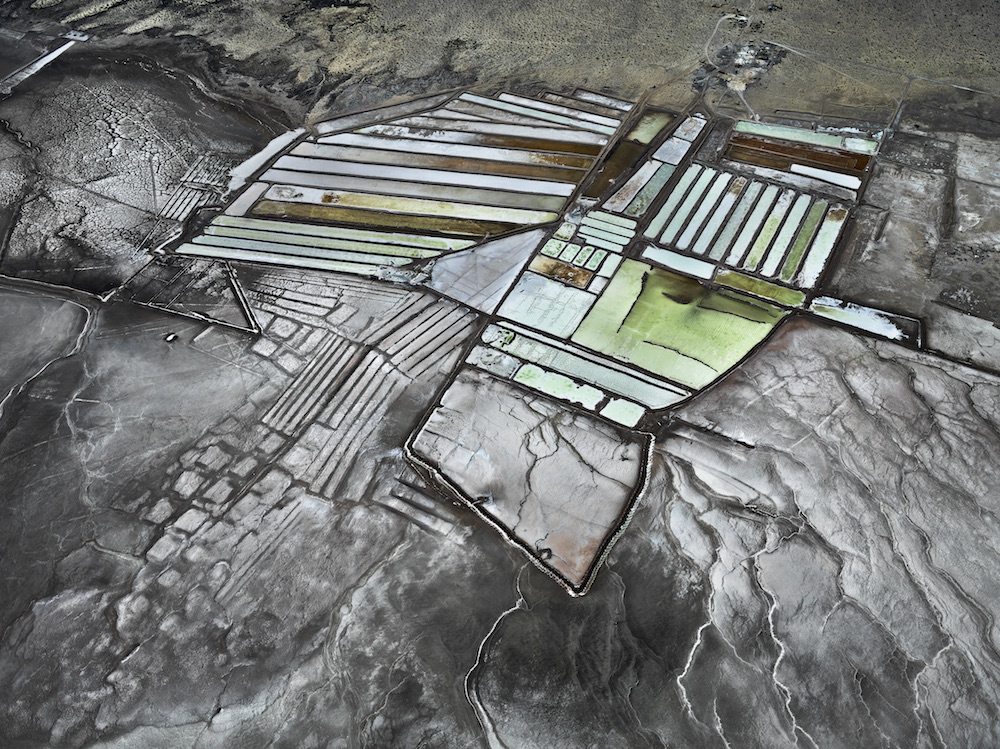

©️ Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto and Flowers Gallery, London

Edward Burtynsky, Colorado River Delta #8, Salinas, Baja, Mexico, 2012

“I’m looking at humans and what they’re doing to the planet as if I were an alien,” Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky told an audience at Photo London a couple of years ago. His documentation of the Anthropocene—the name given to the geological epoch in which we’re now said to be living, where for the first time in the Earth’s history man’s actions are irreparably reshaping nature—is both beautiful and terrible to behold.

—Robert Shore, creative director

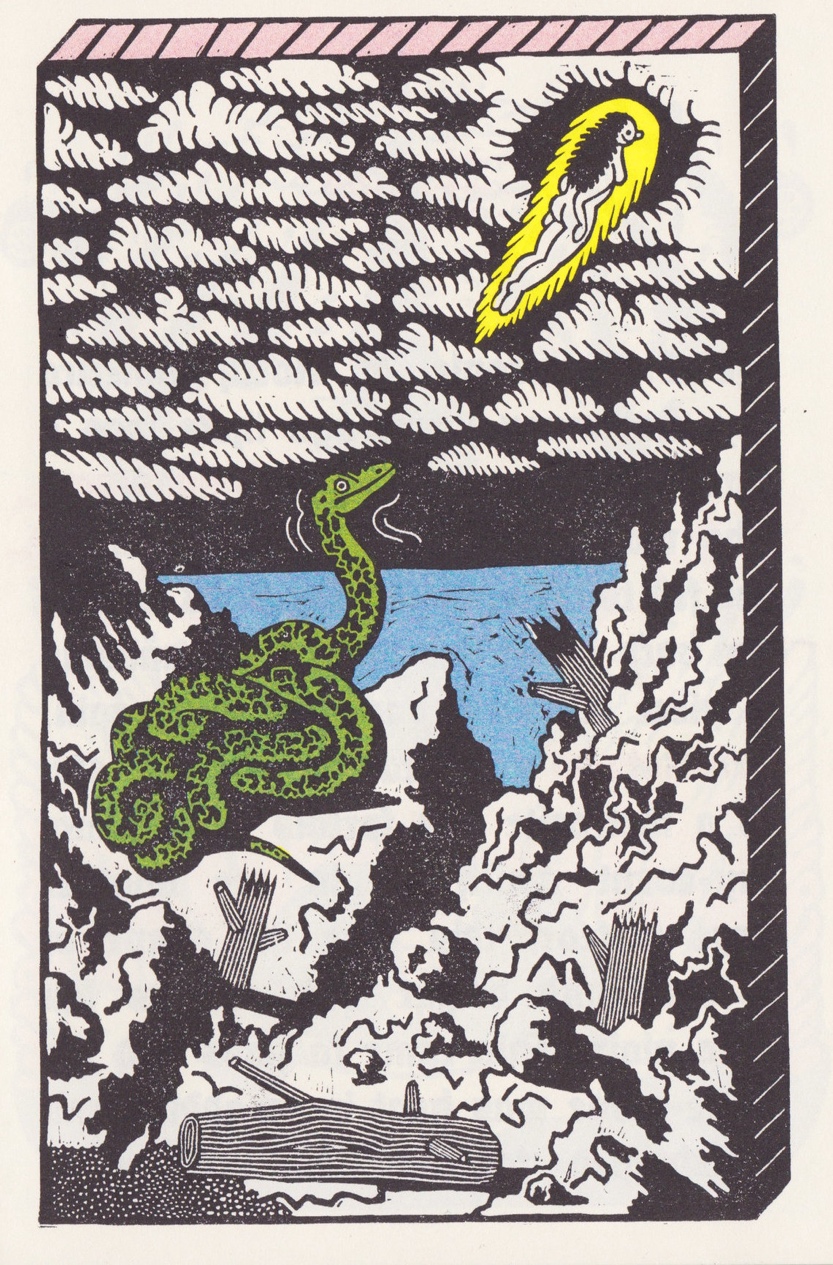

Sophy Hollington, Puggareetya, 2017

This mysterious linocut by Sophy Hollington tells the story of Puggareetya, a member of the Aboriginal Plangermairrener in north-east Tasmania. According to the myth, she fought a monstrous snake, smashing the ground around it to create the surrounding landscape. The furious beast cast her into the heavens, where she was held by the sky-spirit Mienteina and continues to cause mischief to this day. The tale naturally alludes to superstitions around bad weather and earthly tremors, but this image could just as easily be interpreted as depicting the plight of our planet, as humans take to the skies, either oblivious or unconcerned about the devastation they have wrought.

—Holly Black, editor at large

Lori Nix, Library, 2007

We all know the direction we’re heading: more melting icebergs, more blazing deserts, more extreme flooding and forced migration. There’s no way to see what’s going on around us, or to think about the global political policies that involve the environment, and not feel afraid. Taking your reusable bag to the supermarket is a sweet gesture but it’s very literally only going to help the tip of the iceberg. Lori Nix makes disaster dioramas and photographs them. They are cathartic to look at and feel like wistful visions of our future. Human life is being swept away by decay and destruction but nature is empowered. At least something survives.

—Charlotte Jansen, editor at large

Julian Rosefeldt, My Home is a Dark and Cloud-Hung Land (Nr. 2), 2011

Julian Rosefeldt’s moving image and photographic work meditates on humanity’s complex and often strained relationship with nature. By superimposing contemporary political and environmental crises upon landscaped cultural fables and clichés, ranging from Bavarian enchanted forests to mythological Western narratives, he proves the landscape—whether man-made or natural—to be the connecting fabric where culture, human history, politics and environment collide.

—Alice Bucknell, staff writer