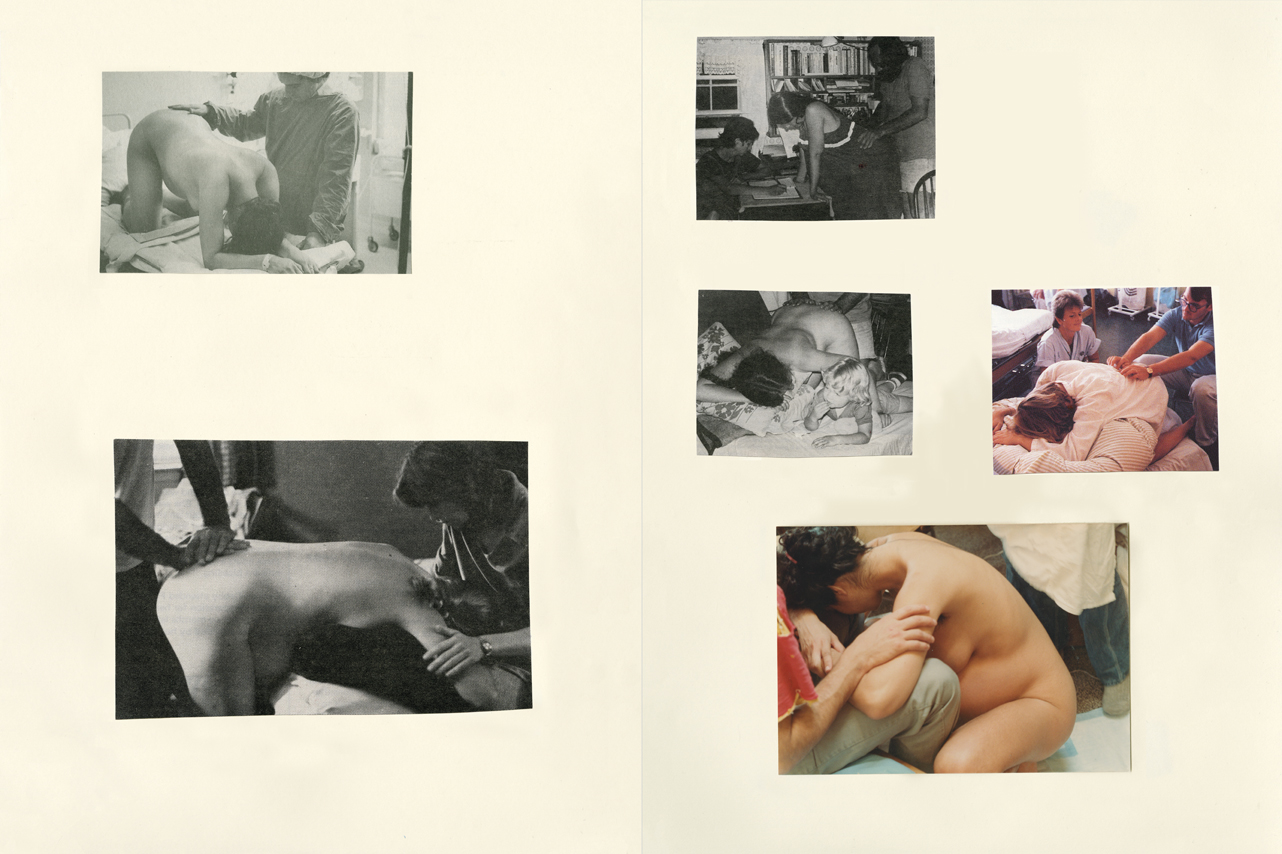

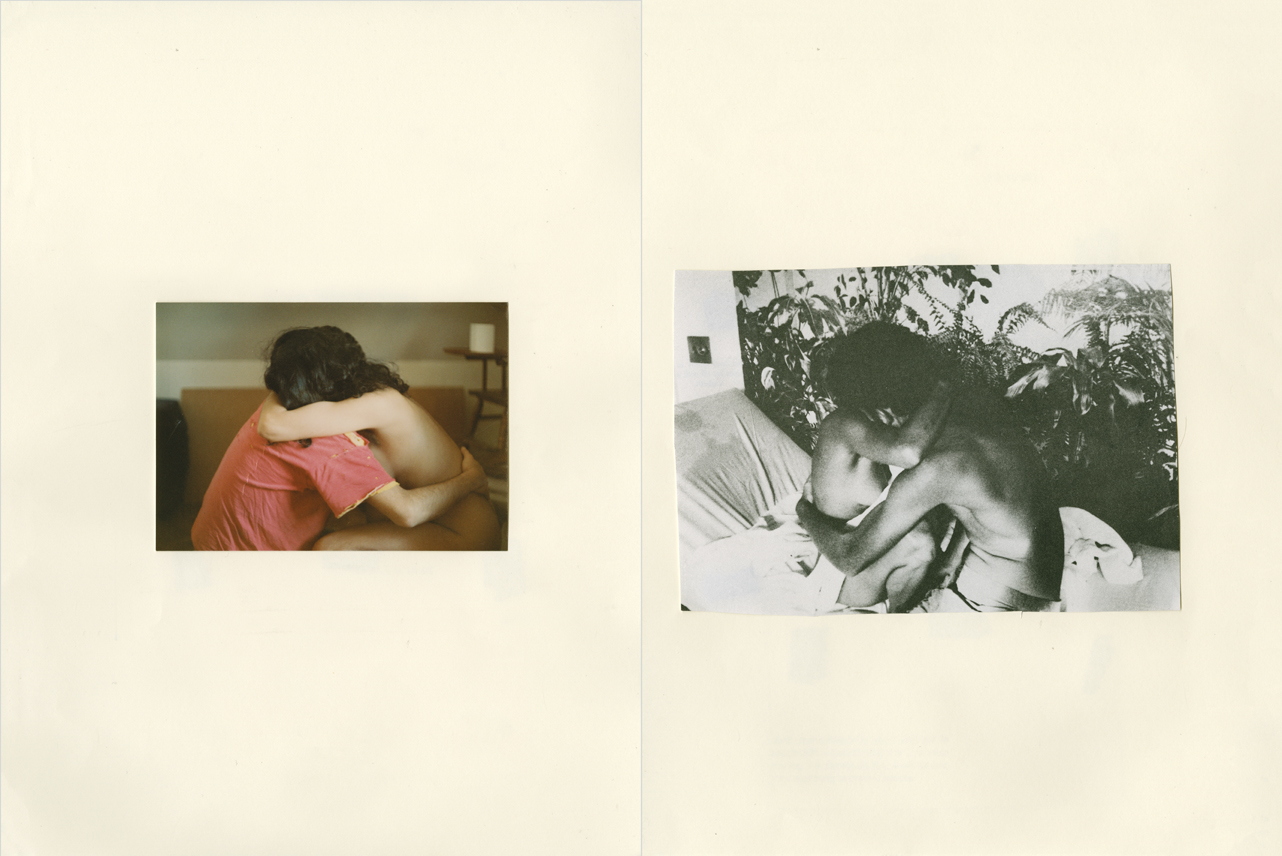

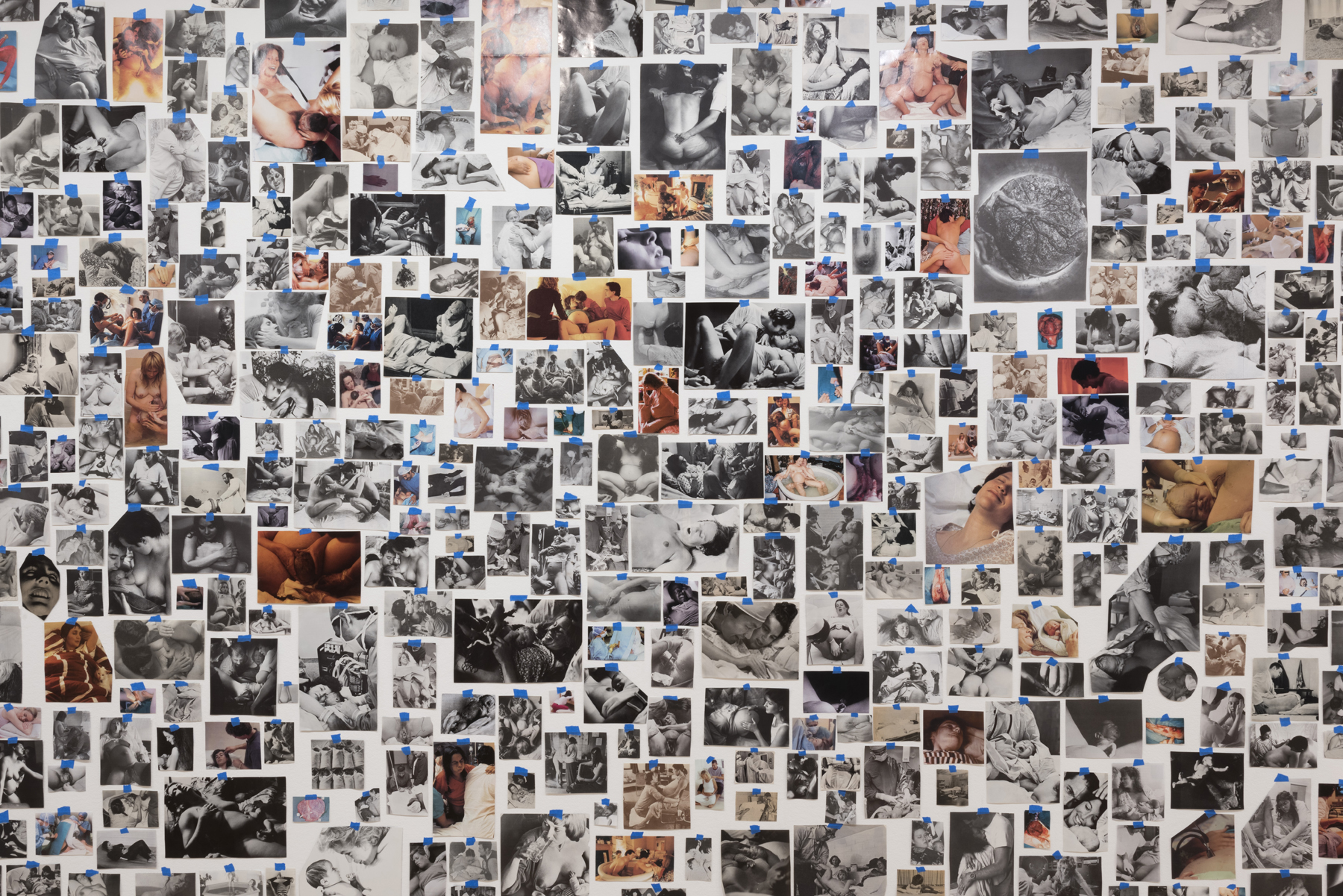

Carmen Winant’s project, My Birth was published as a book and is currently on show to the public at the MoMA in New York as part of Being: New Photography 2018. Over the course of a year Winant collected more than 2000 photographs and written accounts documenting childbirths in the US, including her own experience of giving birth and her mother’s. The extensive work was compiled as she was expecting her second son, who was born as the installation at MoMA opened. The work is a breathtaking insight into the life-changing experience of birth, something that, as Winant explains, is rarely talked about or seen in the public sphere.

Why do you think birth has been such a rarely discussed (and depicted) topic in art?

The most obvious reason here will surprise no one: birth is an action that women perform that is specific to their bodies and their narratives. Anything in this category—menstruation, abortion, breastfeeding, even rape—are generally considered less intellectually serious, less rigorous. Art history (and its standards) is a reflection of culture; if we live within societies that do not deem birth a worthy subject, we won’t see it in art either.

Exactly—as you write in your book intro, there’s a bigger question around this obvious gap.

One thing I could add—and acknowledge—is that birth is obviously an intimate, vulnerable and oftentimes private experience for many women and families. It is not something we do in a public space, in fact it is intensely private. Any experience that we have like this (abortion may be another example, or miscarriage) can feel difficult to share. Even if we are aware that we are not alone, it can often feel this way.

Would you tell me about your own two birth experiences?

My births were not too anomalous: both were vaginal, both were in a hospital, with a midwife. The second one moved faster than the first, as promised. I was induced with pitocin both times, as I went too far past my due date(s). My first birth was about thirty-two hours, start to finish; my second one was about eight and a half. The main distinction was that I got an epidural towards the very beginning of my second birth as I had fallen on the stairs and severely injured my coccyx when I was thirty-nine weeks pregnant. That pain made pushing, and even laying down flat on my back, otherwise impossible. I’ve had to struggle with some regrets about that to be honest—I could barely feel myself pushing, or my son coming out of me, and I was pretty foggy—but ultimately he was healthy, and so I was I. Like so many women, I had to measure the needs of my own comfort up against the needs of feeling the birth process.

There is so much pressure around that. I feel that women are sometimes even ashamed to admit they have had any drugs because there’s this expectation that that’s not doing the real thing, somehow. Which is crazy! One thing that stayed with me for quite some time after my birth was a state of shock at how extreme it is and yet it’s passed off as so normal, ordinary… I don’t think anything could have prepared me for it but it was still such a strong experience. I was amazed I wasn’t more aware of what it’s like. And as you say, I could hardly remember any women I knew talking in any detail about their experience.

That was the very feeling that led to this whole project really: I was shocked, amazed, transformed. Birth struck me as both surreal and hyperreal. Someone asked me at one point in another interview about “normalizing” birth and I told them that that wasn’t really the aim. I wanted to make this experience visible, to examine and study it and take it seriously; it is ubiquitous, but there is nothing normal about birth.

I thought it was interesting how you called the work My Birth. Do you feel the experience bonded you with other women who have given birth?

That title was a really deliberate move, and it came to me early on. I stole it, actually, from the 1932 Frida Kahlo painting of the same name (that I write about in the book). The birthing figure in that painting is shrouded, maybe even dead; a giant baby emerges from between her open legs. I was struck by this title—My Birth—in that I didn’t know who to assign it to. Who, in other words, “owns” the birth? Is it the mother (I often refer to “my birth” with Carlo) or the child (who one day might describe his own deliverance, this same moment, as “my birth”). We share this moment, as I share “my birth” with my mother who can also lay claim. This flattening of experience across generations essentially informs my own understanding of birth.

Why did you decide to go with photography for this and why pictures from printed matter, and not, say, the internet?

Generally speaking, I collect found pictures because they have their own histories outside of me. They have been touched by other hands and moved through other people’s lives. They are objects as much as they are images: this intrigues me. In this project I am also interested in a specific time period: the seventies, during which time women came to be “liberated” in some corners of the world. Feminism brought with it the notion that knowledge was power, and this included knowledge about the workings of one’s own body. Before this moment in history, women in this part of the world had very little sense of, or control over, their reproductive selves. These images were in fact the very same ones that circulated as a means of sharing this knowledge as a form of political power, agency and freedom. They are primary objects.

I was also intrigued about why your mother had her births photographed—not many women do this as far as I know?

My parents were politically-oriented hippies, a part of the new left movement. My mom worked in a women’s health clinic in San Francisco at the time; they were pretty attuned to and interested in birth (and would go on to have three children together). The thing that I love most about these pictures—even more than the fact that the birth was photographed—is the number of people present. They are friends, cousins, neighbours. Some of them came in and out during the process. My mother, who is totally nude, appears completely at ease with the small gathering. It really kind of turns upside down this notion that birth is a thing to be done in private, alone and away from the gaze of others.

I read the comments on your Instagram about the lack of people of colour in those found images—that reveals another aspect to this history that is so personal, private and at the same time, the essence of being human.

It was tremendously hard to find images of non-hetero couples and non-white women in this collection process. I was eager to demonstrate a wide range of bodies and kinds of births. I searched and searched; I so often came up short. Ultimately the work came to be about that lack as much as anything else—all the bodies who were not there. I spoke about this lack in the audio that attends the work, and made sure that the language on the wall label also reflected it. How to speak to something that isn’t there, pictorially? Language is a start.

Images (unless stated): installation view of Being: New Photography 2018 at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 18, 2018–August 19, 2018 © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Kurt Heumiller