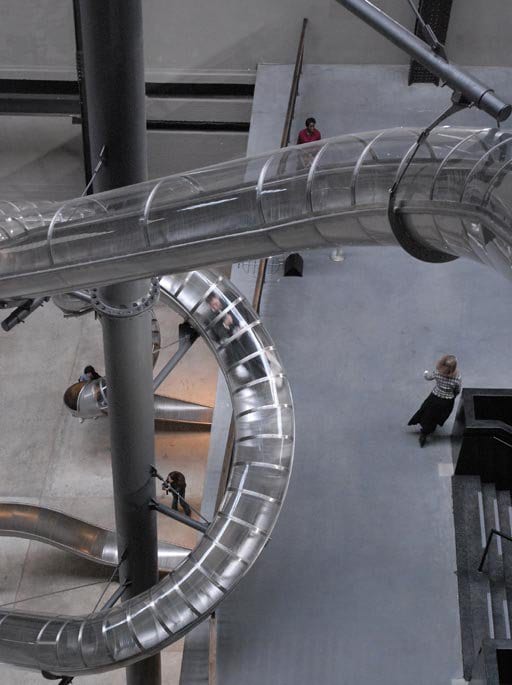

Long before Carsten Höller—described by the Guardian as “the authentic Willy Wonka of contemporary art”—turned the Hayward Gallery into a veritable Pat Sharp’s Fun House (in 2015’s Decision), he had been turning art and art-viewing quite literally upside down. His 2006 piece, Test Site, merged sculpture, spectacle and silliness: it took the form of five huge, shiny slides in Tate Modern’s cavernous Turbine Hall. “I don’t know a lot about art,” the primary schoolers likely muttered. “But I know what I like.” And what they like, surely (as with many adults), is playing about.

Not only does this make the piece a masterstroke when it comes to school trips (Cultural! Enriching! Fun!), but in terms of cementing your reputation as an artist who doesn’t take themselves, or the art world, too seriously. Höller has spoken of delighting in the combination of the visual spectacle of watching others use the slides, and the “inner spectacle” experienced by the sliders—a jolt of fear and pleasure in one rapid descent.

Höller’s choice to use slides as medium is of course no accident: that mixture of panic and joy reflects their usual appearance in amusement parks, playgrounds or emergency exits. The German-born artist told Tate that his intention with Test Site was to “extend the use of the slide”—make it for all, not just kids, or those facing an emergency. The artist had been using slides in his work since 1998, but this felt like the moment they really made their descent into our public consciousness; in London at least.

The piece’s name riffs on the idea that there were five slides to be “tested”—visitors could experience rides of varying shapes and sizes, “mainly to see how they are affected by them, to test what it really means to slide,” said Höller, “… this applies both for those who actively engage in the process of sliding, and those who watch. People coming down the slides have a particular expression on their faces, they’re affected and to some degree ‘changed’.”

“The state of mind that you enter when sliding, of simultaneous delight, madness and ‘voluptuous panic’, can’t simply disappear without trace afterwards”

His Tate piece felt like something of an ushering in of a new, playful approach for such vast institutions. Things got bigger, bolder—spectacle trumps spectatorship. Similarly, viewer becomes performer, and vice versa. “The performers become spectators (of their own inner spectacle) while going down the slides, and are being watched at the same time by those outside the slides,” said Höller. He went on to suggest that using slides “on an everyday basis” can actually transform us—far away from the gallery (or indeed the playground): “The state of mind that you enter when sliding, of simultaneous delight, madness and ‘voluptuous panic’, can’t simply disappear without trace afterwards.”

In this sense, he suggested, the “test site” went way beyond the Turbine Hall and “to an extent, in the slider or person watching who’s stimulated by the slides: a site within.”