Cataloguing objects in an unfolding catastrophe is a hard task, and one that is full of ethical implications. It’s a task made even harder when the crisis is ever-evolving and there is no clear end in sight; harder still when right and wrong appears to evade

even those who made up the rules in the first place. Museums in the UK have worked hard in recent years to democratise their ways of collecting to create a sense of dialogue and ownership among the public that they serve. Now, collection teams find themselves in a position that highlights just how politically charged their roles can be.

Should the V&A choose to archive photographs of the van-mounted billboard that recently showed up outside Dominic Cummings’s house, playing footage of people unable to visit their dying loved ones? How does the Science Museum go about cataloguing the growing evidence that BAME communities are dying in greater numbers of Covid 19? Will the Museum of London have a headphone set where you can listen to the viral WhatsApp audio message about the Wembley lasagna?

The challenge of balancing their roles as documentarians with their responsibility to public sentiment and societal wellbeing is a dilemma that museums and their collectors were somewhat prepared for. But in the midst of a bitterly politicized health disaster, it becomes increasingly difficult to make these important decisions.

On 30 March, the London Transport Museum published Contemporary Collecting: An Ethical Toolkit for Museum Practitioners. It asks questions about recurrently problematic issues for museums, such as representations of hate speech, the simultaneous acquisition of trans-exclusionary and trans-inclusive material, the decolonisation of museums and restitution, and representations of climate emergency. Most relevant to the current crisis is the toolkit’s section on dealing with “trauma and distress”. “Contemporary collecting often involves being reactive—acting quickly and in response to events or developments, sometimes while they are still unfolding,” the document reads.

Being seen to be dynamic and part of the conversation is something that museums have increasingly embraced. The shift is borne out of a desire to appeal to the public’s imagination in a cultural moment obsessed with its own currency and immediacy. But the pandemic has found a way of slowing things down, even for the methodologies of collecting.

Senior design curator at the V&A, Brendan Cormier, points to the fact that rapid response collecting was a term originally coined by the V&A to denote an elastic approach. “Rapid response collecting has been largely beneficial,” Cormier points out. “If you type ‘Spanish influenza’ into the collection, our search engine reveals zero objects… It goes back to that unwritten rule about not collecting until fifty years have passed.” At the time social history didn’t seem to fall within the remit of a design museum, which the V&A predominantly sees itself as.

“Being seen to be dynamic and part of the conversation is something that museums have increasingly embraced”

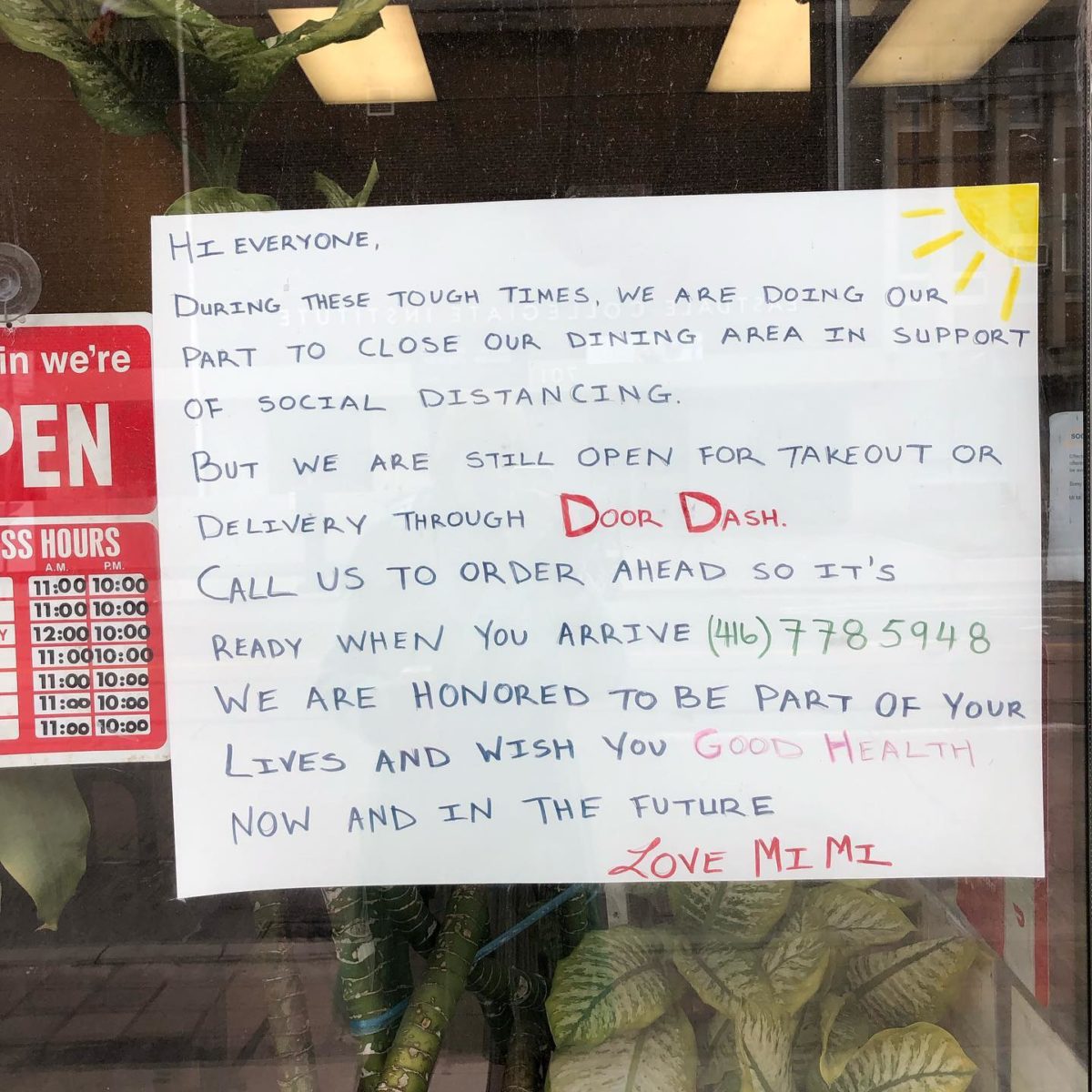

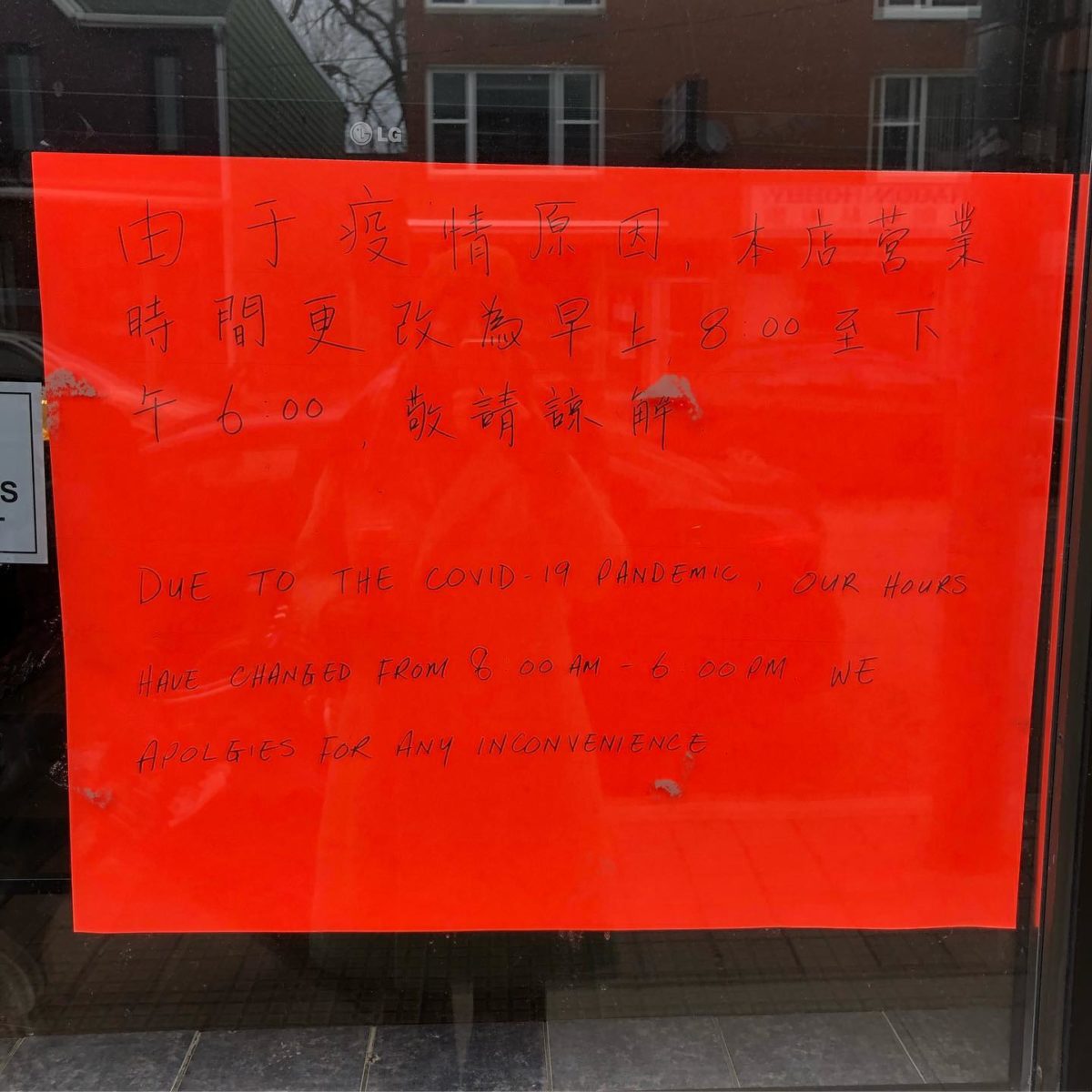

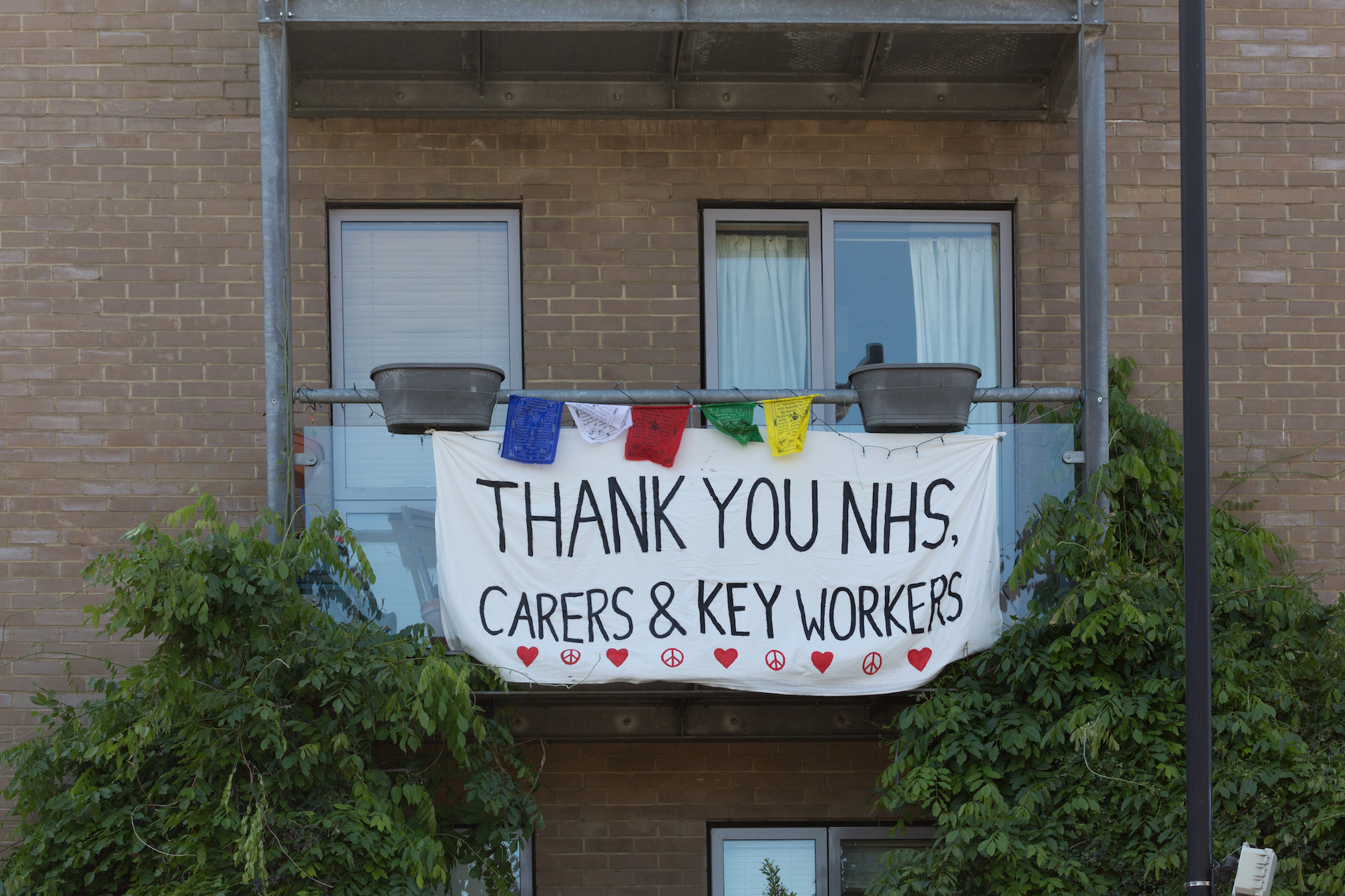

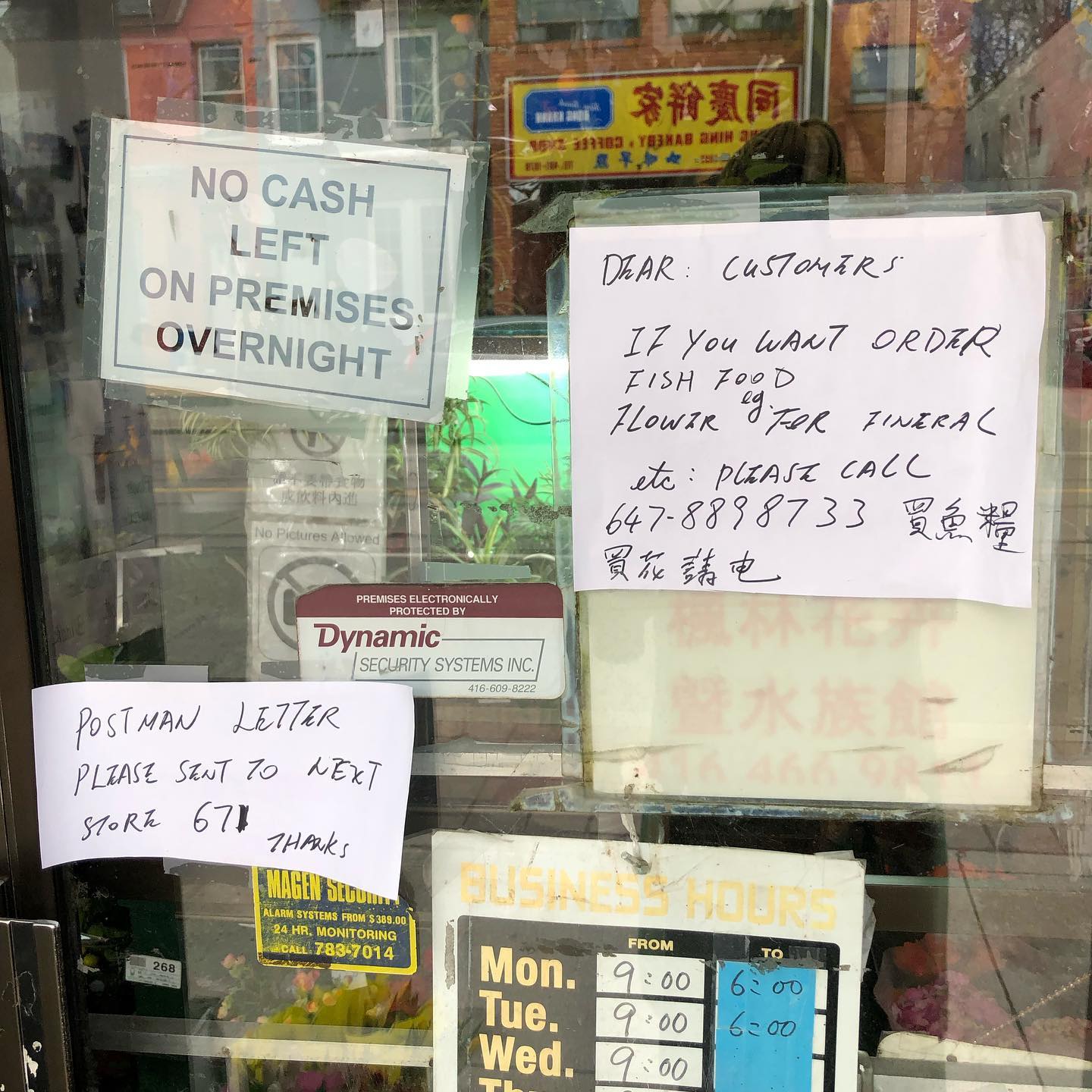

Cormier is currently overseeing the V&A’s Pandemic Objects blog, which invites writers to reinterpret day-to-day objects in light of the crisis, as well as an open-call for submissions of hand-drawn NHS signs. “In a weird way the pandemic has become this crystal clear lens which highlights a lot of the contradictions we’ve had already floating about in the world.” He also points to the voluminous quantities of digital and social media based objects that have been produced during lockdown, which present a further ethical and privacy quandary when it comes to cataloguing.

Cormier believes ethical toolkits are useful, but also acknowledges that public sentiment informs how things are collected. This, he explains, brings up the idea of “accessioning” objects. Accessioning an object is the process by which an object is added to (or, in some cases, removed from) a collection after its merits are re-interpreted during a consultation with the public and external consultants to the museum.

It is a process that falls under the “RC” or “Revisiting Collections” methodology, whose purpose is to democratise the process of collecting, acknowledge hidden histories, and carry out a process of redress in some cases. The process is largely seen as a positive, with institutions like Tate, which has the largest “Interpretations” team in the UK. The role of the interpreter, in this context, is to form a filter between the collector, curator and wider team. They assess the way in which an item might be perceived by the museum-goer, and how it sits within the cultural context of the day.

It is a thorny role that throws up numerous points of contention: the potential coddling of the public; the no-platforming of certain artworks or objects deemed offensive; the perceived rewriting of history; and the influence of fleeting but intense online outrage. However, for the most part, the process of revisiting and reinterpreting collections has had the effect of diversifying and contextualizing—both of undeniable benefit.

When references to Coronavirus employ the images and language of war, the museum’s role can feel elevated to that of keeper of truth or contested site of remembrance. “Political opinion is acutely divided, and many people will encounter media and consume culture quite separately to those with opposing views. Museums and museum collections are one place where visitors are witness to the same thing,” writes Jen Kavanagh, one of co-authors of the Contemporary Collecting toolkit. Kavanagh says that museums are feeling the pressure to respond rapidly to Covid 19, but that “not rushing into anything is probably the safest way to ensure that the collecting of this event is done ethically, sensitively and to the greatest effect.”

“Objects in a museum, by their inherent placement, transcend their day-to-day use and become substitutes of reality”

She believes that, given the politically divisive nature as well as the human cost of the crisis, “taking the pressure off the perceived need to have to collect in the now” would be beneficial. She points to a very recent acquisition, by the Museum of London, of an object pertaining to the 7/7 London Bombings. “The relevance of this and the importance of the object are no less significant just because it’s fifteen years later,” she says. “Perhaps it’s only now that the donor feels able to speak about it and wanted to ensure their story was captured.”

Objects in a museum, by their inherent placement, transcend their day-to-day use and become substitutes of reality. Whether they be tactile or digital, the objects catalogued around the Coronavirus crisis will become signposts in a narrative told to future generations about what is likely to be the biggest socio-political event of our lifetimes.

Museums and their teams have been conscientious about collecting with sensitivity at this time, and have avoided approaching members of the public too fast or sensationalizing the already sensational. They are faced with the difficult task of having to sift through the immense volumes of daily news and developments during the crisis, along with the incalculable number of personal stories of illness, and make a value judgment as to their relevance and import.

But perhaps collectors also have a duty to approach things in a slower fashion, drop the “rapid response” methodology that has been prevalent, and make considered choices that are neither swayed by public debate nor the need to produce. At a time when statistics are being fudged, blogs rewritten, and rules reinterpreted in self-serving ways by those who have the power to do so, collectors and museums can slowly and deliberately catalogue the things on which the reality of the present is constituted. In doing so they preserve them to history, not as an act of defiance, but as an act of truth-telling.