“Vatican S/S 21 collection is [fire emoji],” reads the Instagram caption beneath Portland-based artist Eric Long’s meme-ified Vatican gift shop souvenirs. Printed in elegant type onto baseball caps, T-shirts and tote bags are the words “God cannot bless sin”, quoting the official verdict given by the Vatican in March in response to whether the Catholic Church could bless gay unions. “Free rosary with purchase” promises a cheeky promo sticker.

Long’s caustic graphics visualise the cruel absurdity of the Vatican’s judgement, which is one of the latest flash points in institutionalised Catholicism’s longstanding apparent antagonism towards the LGBT+ community (the most recent being the Vatican’s opposition to an anti-homophobia bill).

But while the Holy See continues to seek to distance itself from queer culture, many artists are actively turning to the visual lexicon of religion as a tool for self-expression. In March 2021, openly gay rapper Lil Nas X outraged conservatives by pole-dancing down to hell as the devil in the music video to MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name).

The aesthetics of catholic shrines have proven fertile ground for bold stylistic and political statements. With their opulent designs, sensuous textures, and chromatic mix of multimedia elements, shrines sparkle with undeniable campiness.

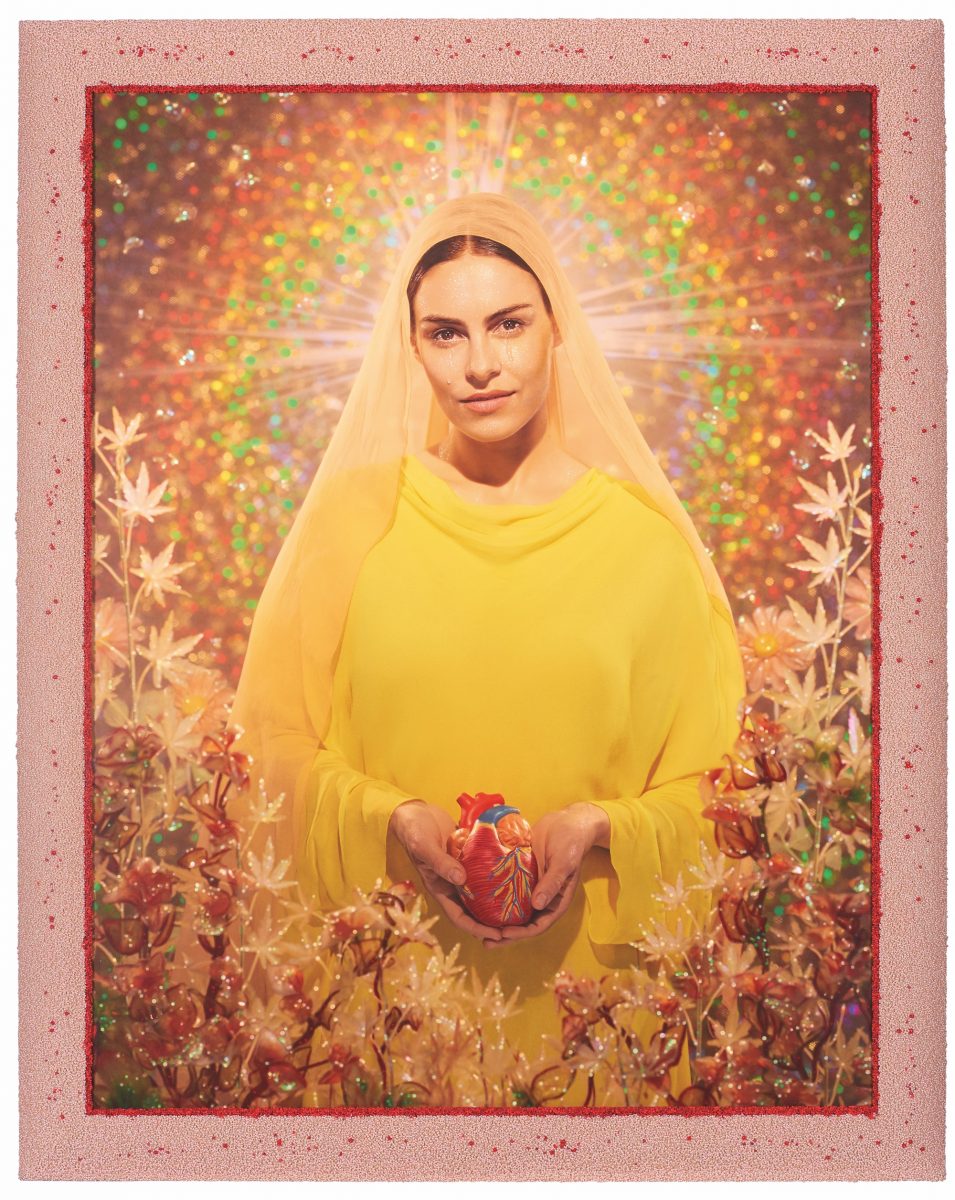

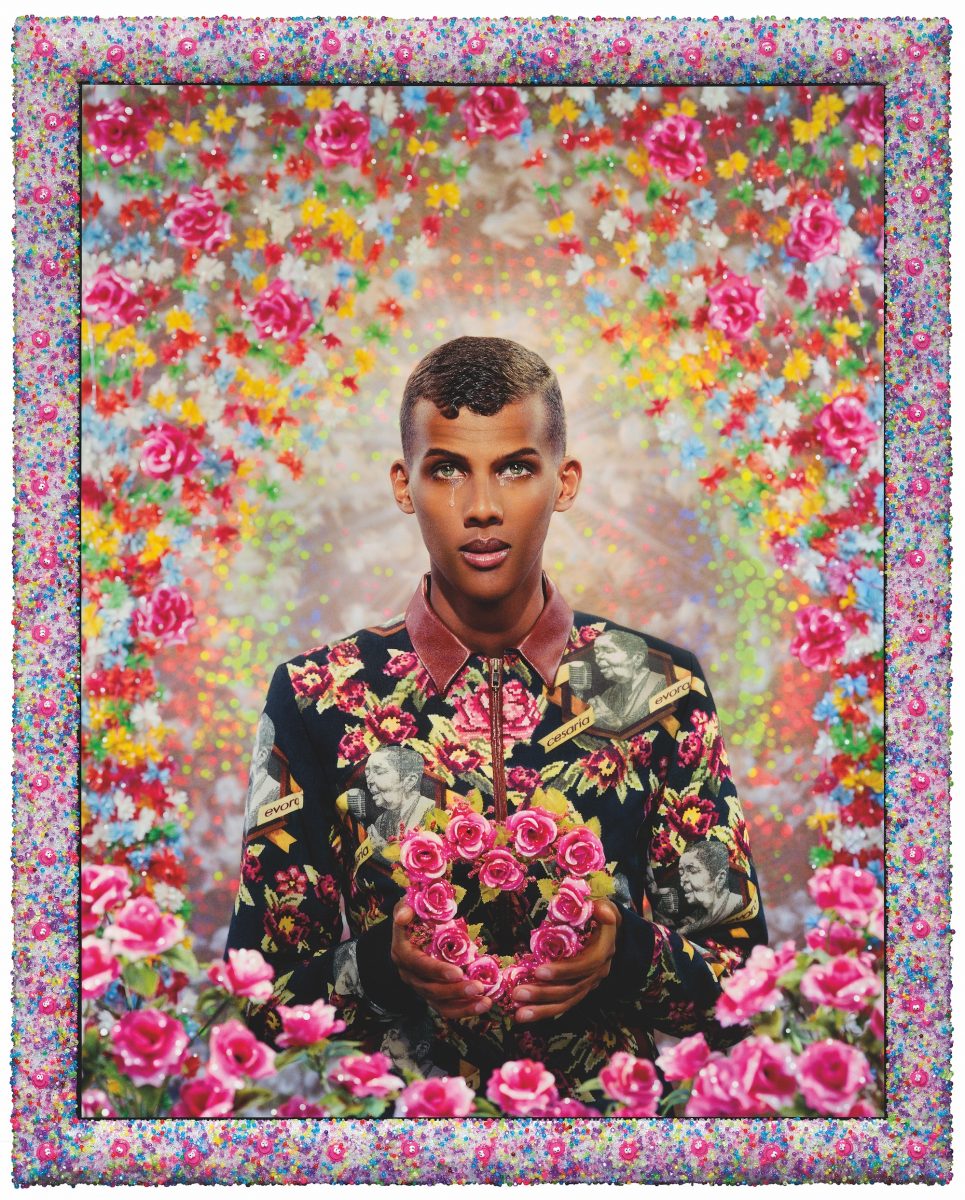

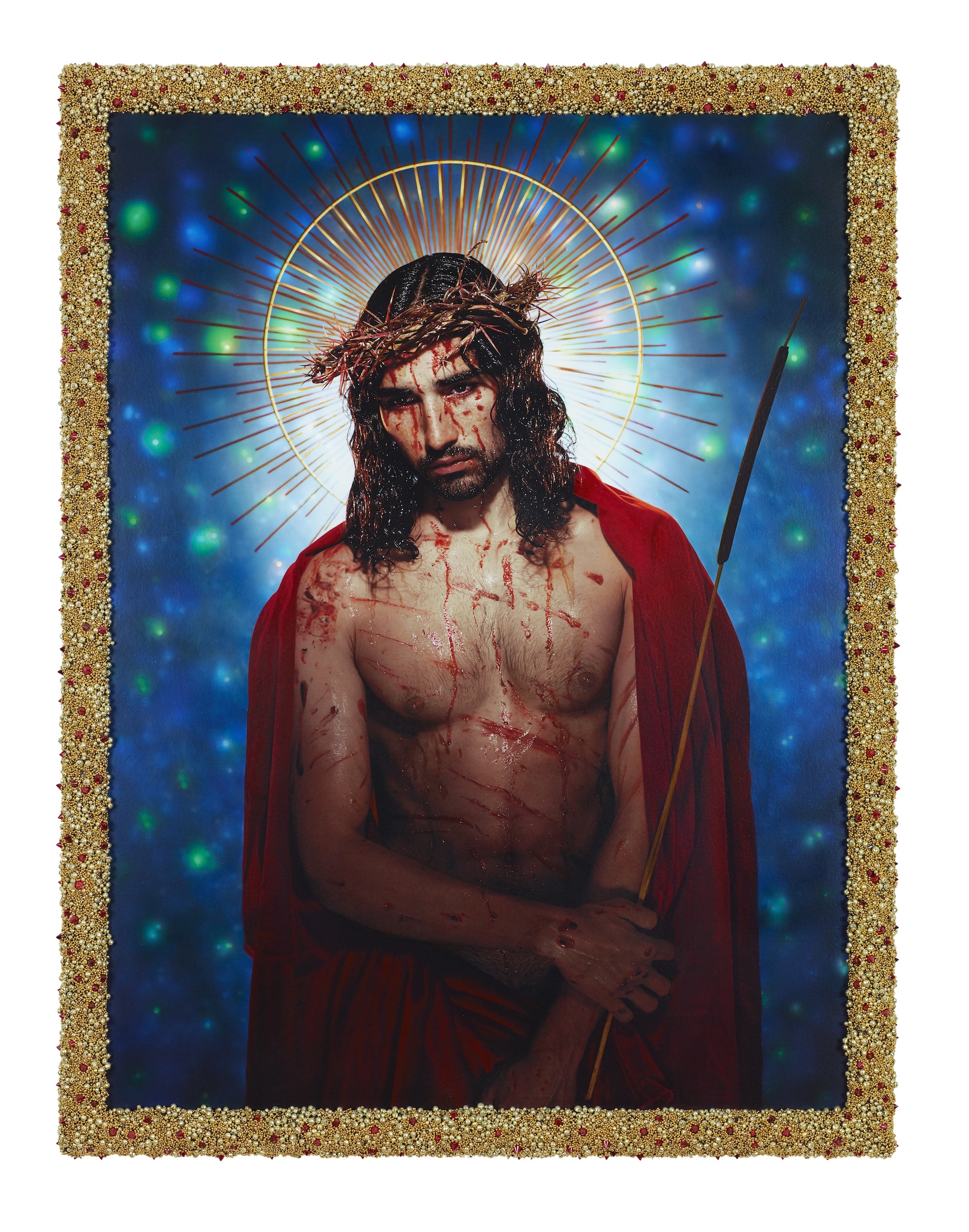

“Camp is the glorification of character… a person being one, very intense thing”, wrote Susan Sontag in Notes on Camp (1964). Few are more fluent in what Sontag terms “the spirit of extravagance” than French artistic duo Pierre et Gilles. High-fashion photography meets pop art and soft-core porn in their portraits, which transform celebrities into mythological or biblical characters.

Model Willy Cartier becomes Le Christ aux Outrages (Christ in Outrage) (2018); actress Hafsia Herzi is part of La Vierge à L’Enfant (Virgin and Child) (2009); and singer-songwriter Clara Luciani is La Madone aux Fleurs (Our Lady of the Flowers) (2019). The duo accentuate their subjects with layers of elaborate borders, emulating the structural framing of religious icons in tabernacles and niches.

Experimental artist duo McDermott & McGough are responsible for perhaps the most immersive queer shrine to date. The Oscar Wilde Temple, installed in a chapel in Manhattan in 2017 and then in London’s Studio Voltaire in 2018, paid homage to the Victorian poet and playwright who was imprisoned for his homosexuality. A statue of Wilde stood at the altar, decked out as a provocative substitute for Christ.

In a nod to the 12 apostles, the installation also honoured 12 recent individuals who suffered for their sexuality: Marsha P Johnson, Sakia Gunn and Justin Fashanu among them. A book of remembrance to the victims of the AIDS epidemic situated the Oscar Wilde Temple as a space of healing. Playing on the performative element of shrines as a destination of pilgrimage and prayer, viewers became worshippers of sorts, part of a collective ritual of mourning and celebration.

“Catholicism lends itself to drag perfectly: it’s rich, it’s decorated, it’s dramatic. It’s a whole fantasy”

For London-based artist Fipsi Seilern, creating a shrine to the drag queen Virgin X who impersonates the Virgin Mary onstage, was a personal process as much as a creative one. “I’m a lesbian with Catholicism running through my veins”, says Seilern, who was brought up in an Austrian Catholic household. When she began to understand her sexuality, she was burdened by “Catholic guilt”. Mostly known by her street art alias PANG, Seilern “hijacks” the materials of Catholicism to empower her own identity. She’s cut and pasted the Book of Revelation and re-ordered it into “coming out” poetry, and imitates the “restless anxiety” of the confessional in her frenzied, tapestry-style Confessions series.

Trained in classical painting, Seilern had intended to portray the Virgin X on canvas only, “painting them in the manner of the Renaissance Madonna (with a moustache)”. But she wasn’t satisfied with the result. “There’s something somewhat constraining about that method of painting, even if I am depicting a drag queen who hijacks the Virgin Mary,” she admits. “It needed more.”

Seilern looked back through holiday photos of the votive shrines that line the streets of Naples. “A lot of them have these funny at-odds elements in them: photographs of family members, little neon bands, fake flowers, and all these kitsch incongruous objects,” she says.

“While the Holy See distances itself from queer culture, many artists are turning to the visual lexicon of religion as a tool for self-expression”

Transfixed by “those intimate gestures of worship: the kneeling down, the lighting of a candle, lovingly laying down wreathes”, Seilern framed her portrait with a pink neon strip light (“the lesbian colour”), and laid down plastic flowers, candles and a lace doily for a shrine cloth. “Creating the shrine became in itself a ritual for me that cultivated a stronger sense of pride in my own queerness,” she reflects.

- The early Gothic statue of a standing Mother of God with the baby Jesus, c1330, Bavaria (left). Verge d'Itati Corrientes, Argentina, dab l'autorizacion de l'Arqibisbat (Arzobispado de Corrientes) (right).

Drew Caiden is the drag artist behind Virgin X. They grew up queer in a catholic community in small town America, an experience they describe as “interesting on the soft end of the scale, and very traumatising on the darker end of the scale.” But the Virgin Mary, pervasive in Catholic shrines, was always a source of comfort. “I gravitated towards Mary: I didn’t feel judged by her, I didn’t feel she thought I was an abomination,” they say.

“There was a lot in common between my queer experience and the experience of this woman, who was essentially silenced and othered in her own narrative,” they add. Caiden’s drag act is all about humanising Mary and giving her a voice. In response to allegations of blasphemy, Caiden asserts: “All I advocate for through the character of Virgin X is equality. The irony of the church is that despite this rule ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you’, they continue to advocate for discrimination. That’s blasphemous!”

“Catholicism and queerness don’t have to cancel each other out; one can amplify the other”, Seilern argues. Caiden agrees, loving appropriating the decadent trappings of the church. “Catholicism lends itself to drag perfectly: it’s rich, it’s decorated, it’s dramatic,” they explain. “It’s a whole fantasy.”

The extravagance of Catholic iconography is innately hierarchical, embroiled in power dynamics and focused on the diminishment of the self in the eyes of a higher authority. But these queer shrines do the opposite: they usurp the materials of an oppressive establishment to bring queer identities, desires and experiences to the fore. In doing so, they make saints of the living.