“I remember,” says Ian Schrager, creator of the legendary nightclub Studio 54, “when you would enter, you would go through a long hallway that acted like a decompression chamber, and only had a glimpse of the light fantastic.” Then: “the lights, music and kinetic energy exploded right on you and you got swept away by it. It was magical.” By dawn, says Studio regular Rod Stewart, “everyone left in a thick coating of glitter. At least I think it was glitter.” A memorial to the glamour of Studio 54, it is fitting that this book should be clad in highly tactile black satin, as though itching to slip out of your hands and sashay on to a disco-jumping dance-floor. (But if it does slip out of your hands, be sure to step out of the way, as it is a large and heavy tome.)

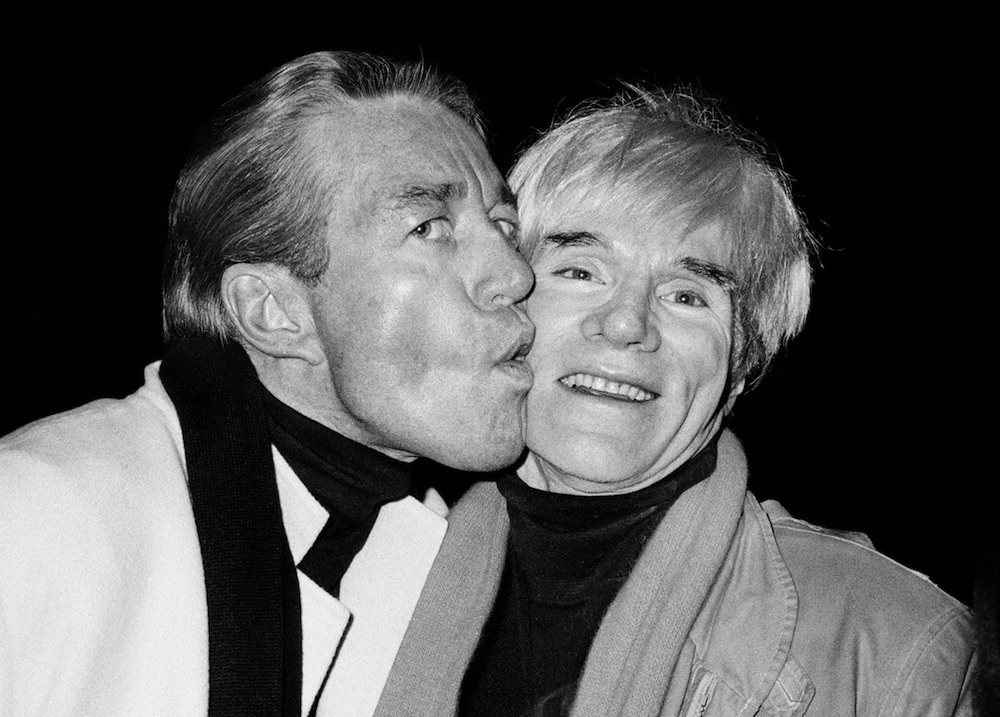

- Halton and Warhol, 1984 © Roxanne Lowit

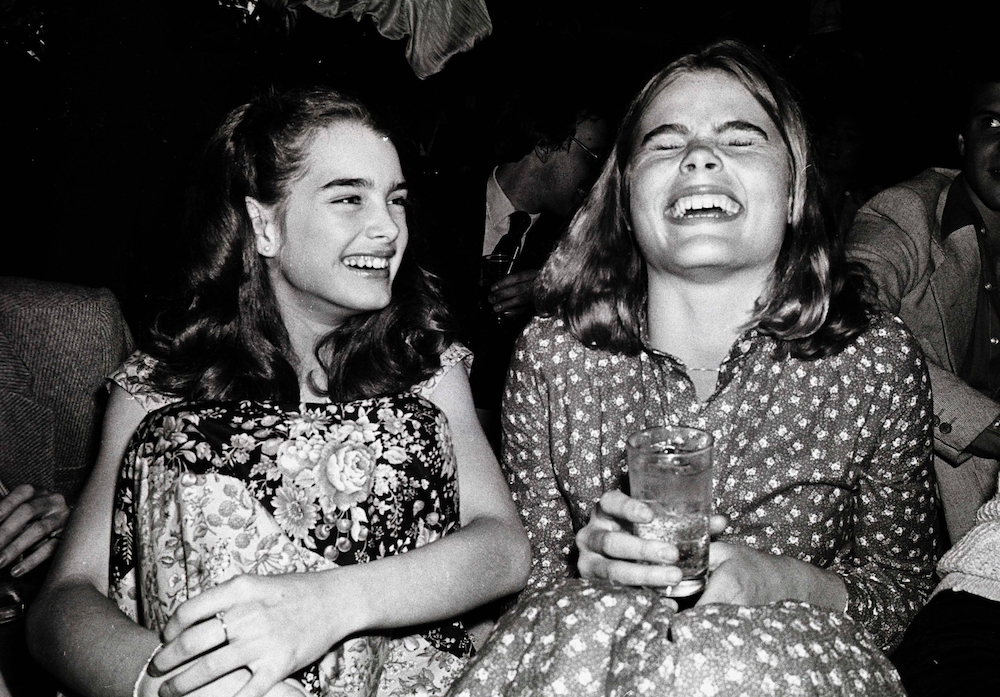

- Brooke Shields laughing with Mariel Hemingway, Studio 54 © Adam Scull Photolink Newscom

How on earth did Studio 54 come to flash and shimmer like a temple of multi-coloured glamour amid the dark grime and squalor of 1970s New York? Schrager’s appraisal of his groundbreaking venture provides an evocative historical context and suggests that it was precisely the broken down and bankrupt state of the city that, driving big businesses and companies to set up offices in Connecticut and New Jersey, created a space for the creativity and experimentation of outliers. Rents were cheap then, and there was, Schrager argues, far less of a pay gap between bankers and ordinary people, who could therefore afford to live and work in the city.

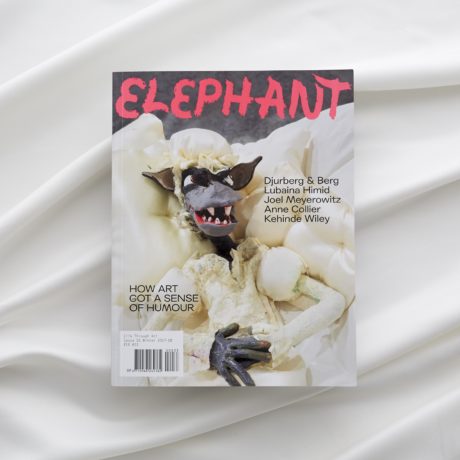

“A memorial to the glamour of Studio 54, it is fitting that this book should be clad in highly tactile black satin”

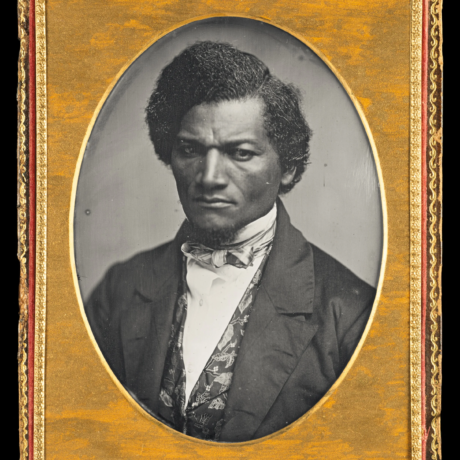

In those days New York was a place of no-go areas, where muggings were very frequent, but it felt edgy and stimulating. The book identifies a deep cultural continuity (of outsider culture moving into the mainstream) between, say, the emergence of fringe artists like Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe, on the one hand, and, on the other, the invention of the glittering scene at Studio 54, whose regulars included Liza Minnelli, John McEnroe, Diana Ross and Truman Capote.

The club lasted from 1977 to 1980, when it was closed down after Schrager’s business partner Steve Rubell said in interview, perhaps unwisely, that they were making more money than the mafia. But this book is less about Schrager’s financial downfall (followed by a spectacular recovery) than about Studio 54 as cultural object and sociological phenomenon, and as a bewitching window into pop culture.

“And yet the club was, Schrager explains, democratic once you made it past the door”

What was so special about Studio 54 was its theatricality. In the abandoned hulk of an opera house on 54th Street Schrager (who until this point had worked as a lawyer) and Rubell created an immersive environment that included 1,500 square feet of mirrors, 400 different lighting effects, and fog and snow machines. The existing theatrical fly rail, still in working order, was used to lower and raise theatrical backdrops (of volcanoes, galaxies, sunrises etc), creating rapid, surprising changes of scenery, “like a ride at Coney Island”. Meanwhile the furniture was designed to be moveable, so that the dancefloor could expand as the night went on. Such was the imaginative ambition of the project that, in a book that is so much taken up with pictures of celebrities having fun, it is perhaps those pages devoted to photographs of the building site and of the finished club lying glamorously empty, with its Deco-style enfilade of rooms, that are ultimately the most thrilling.

Nevertheless, the point of this richly immersive and detailed setting was, of course, that it would be animated by live performers—the crowd that would fill the dancefloor. And the club was wildly successful: “it went viral, as they say today,” Schrager declares. People queued around the block, hoping to make it past the velvet rope. Of his famously selective and subjective door policy, Steve Rubell said that it was, night after night, “like mixing a salad or casting a play” in order to produce the perfect mix of “gay and straight, black and white, rich and poor, uptown and downtown”, a sort of quintessence of New York.

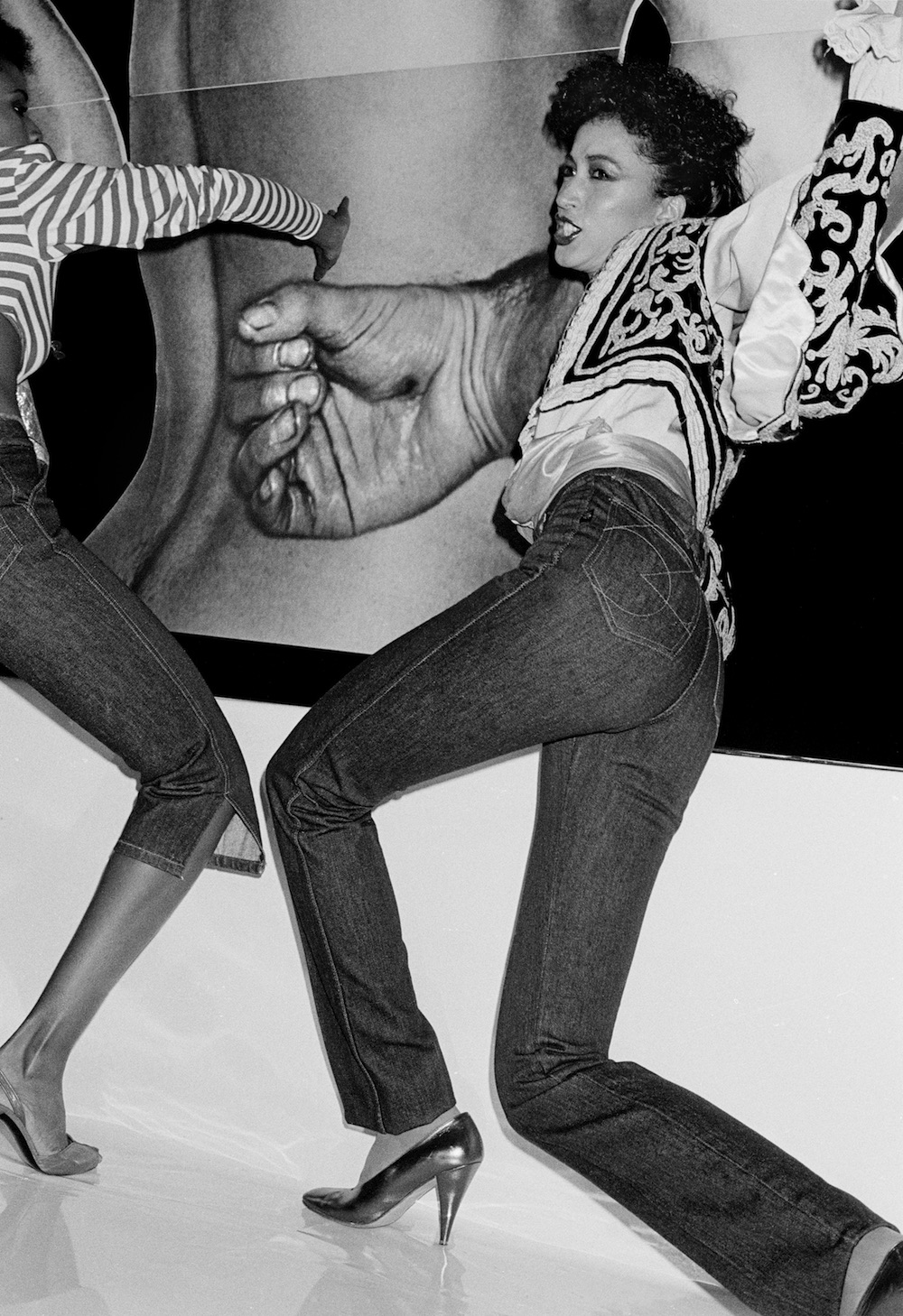

Inside, Schrager wanted to emulate the “non-stop, intense tribal-like dancing” he had seen in gay clubs where the dancefloor was like “some kind of living organism, rolling and pulsating up and down”, and create a space expressive of “wild abandonment”. (Tellingly, Schrager reproduces a stern letter from New York City’s Bureau of Animal Affairs complaining about the reported presence of a leopard and a panther at the club.) Upstairs, the infamous co-ed bathrooms and lounging banquettes encouraged all kinds of misdemeanours: Studio 54 came, crucially, after birth control and before Aids.

What is striking is how intimate most of the photographs of revellers feel, with many resembling a phonebooth challenge, as though trying to cram as many famous faces into as small a space as possible. And yet the club was, Schrager explains, democratic once you made it past the door. Those were the days before social media and before phones with cameras: rather than taking a celebrity selfie, a star-struck clubber might instead have asked Cher to dance.

This feature originally appeared in issue 33

BUY NOW