I first met Chantal Joffe while it was still winter in London. She was preparing for her solo exhibition at the Lowry in Salford, Personal Feeling Is the Main Thing. Invited up to her high-ceilinged studio, where little plug-in radiators kept us warm, our conversation was expansive and sprawling. We jumped rapidly to topics far beyond the art world, touching upon everything from the pleasures of train travel to the tender pains of teenagehood. I was surprised to find her so unguarded, so openly willing to share ideas, memories and observations, and I responded in kind. I became fully immersed in her world, surrounded by discarded paint tubes and canvases at various stages of completion. I’ve long admired Joffe’s deeply personal painting; many show herself and her daughter, Esme, in everyday moments that are as intimate as they are universal.

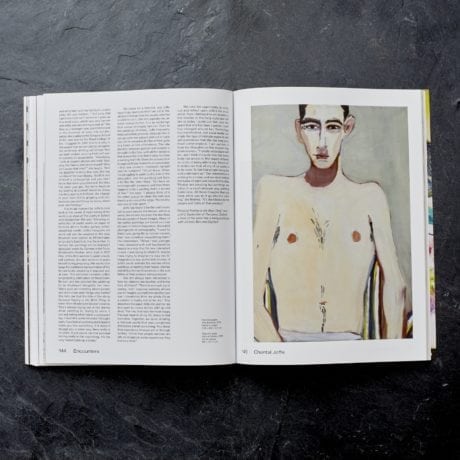

One painting sat opposite me on the floor as we spoke, leaning lazily against the wall, which stood out amidst the many figures and faces lining the large, light-filled room. A dark-haired boy looks straight ahead, his shoulders subtly raised, as if posing for a portrait has hunched them very slightly. He is fully alert, arms held a little away from the body, tense and yet imbued with the thrill of a new experience. After all, he has agreed to sit for Joffe and he is topless. Here is the compassionate honesty that characterizes Joffe’s mark-making, full with the psychological undercurrents to be found when looking—really looking—at another person. I wonder about his aspirations, his desires and his doubts. He is bare and yet concealed, with skin showing but eyes watchful. He guards his thoughts closely, I feel. A mauve shadow falls from his face across his neck and shoulder, a darker tone alongside the paler chest and arms, and he appears at once intensely present and momentarily absent from the picture.

Sitting in Joffe’s studio on that cold winter day, I ask about him, and she tells me that he is a friend’s son, just sixteen years old, and he is called Herb. I recall my own adolescence as I look at him, conjuring a time when excitement for the future is mixed with a certain nostalgia for the childhood that is slipping away. I longed for autonomy, but did not feel ready to accept the responsibility that would inevitably come with it. Joffe has the ability to capture these moments of change, most clearly in her many self-portraits that candidly show her through her own younger days, in the various stages of pregnancy and in the years following the birth of Esme. Sometimes, though, these pivots towards transition can be found in a single image—in the quietly reflective gaze of a teenage boy.

“I recall my own adolescence as I look at him, conjuring a time when excitement for the future is mixed with a certain nostalgia for the childhood that is slipping away”

The changes that the body undergoes during teenage years are some of the most dramatic in our lives, and it is curious to feel suddenly out of control as puberty takes hold. These changes are often felt most vividly not when looking in the mirror, but when perceiving the shift in how others view us. Joffe describes the moment when Herb looked over at the painting after it was complete: “He said ‘Oh, my ear does really stick out’, and you never mean to make a sixteen-year-old boy self-conscious. He’s so beautiful but it’s so heavy to have someone here and have them see what you do. Having a model has a big responsibility and a weight to it.”

The painting becomes a window into how someone else views us, and has the ability to offer an image that is so alien despite the familiar face that we can recognize as our own. It offers a moment to step outside of your body, and to reach towards a form of representation far beyond the mirror or the photograph. Joffe’s fluid brushstrokes convey these tensions, and the shared vulnerability in the relationship between artist and model. Herb at Sixteen, simultaneously shy and strong, makes me remember the self-consciousness of being looked at in teenagehood—as well as the power of looking straight back, and holding the watcher’s gaze.

Personal Feeling Is the Main Thing shows until 2 September at The Lowry, Salford. A book of the same name has been published by Elephant and Victoria Miro