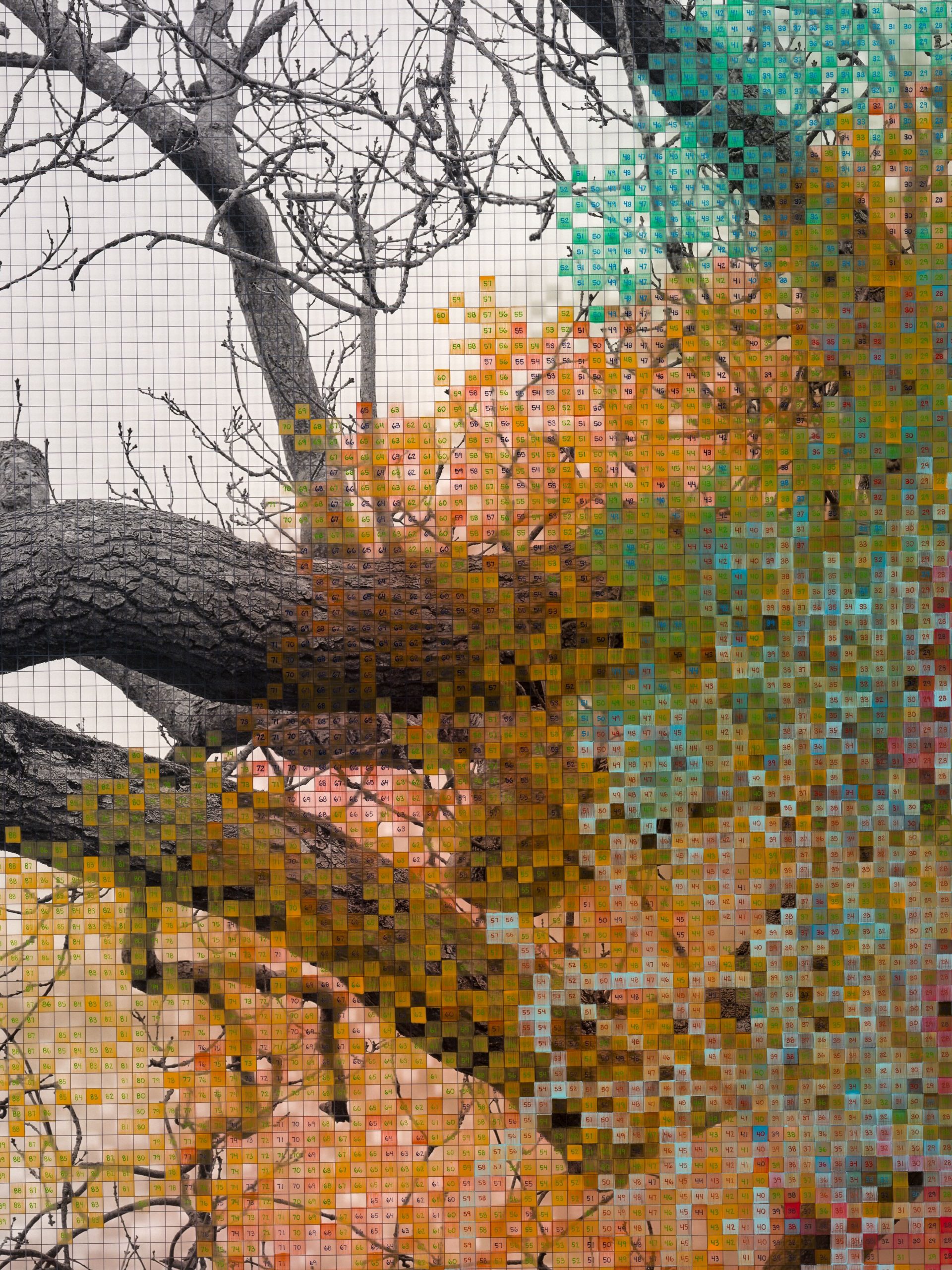

Charles Gaines has been shooting and incorporating trees into his mixed-media artworks for more than 50 years, from young walnuts in California’s San Joaquin Valley, to the Mexican fan palms that line streets along the south side of the state. The Numbers and Trees series began in 1986, but have their origins in Walnut Tree Orchard (1975), where Gaines sketched from photographs onto hand-gridded paper, a union of nature photography and geometry which has evolved throughout his career.

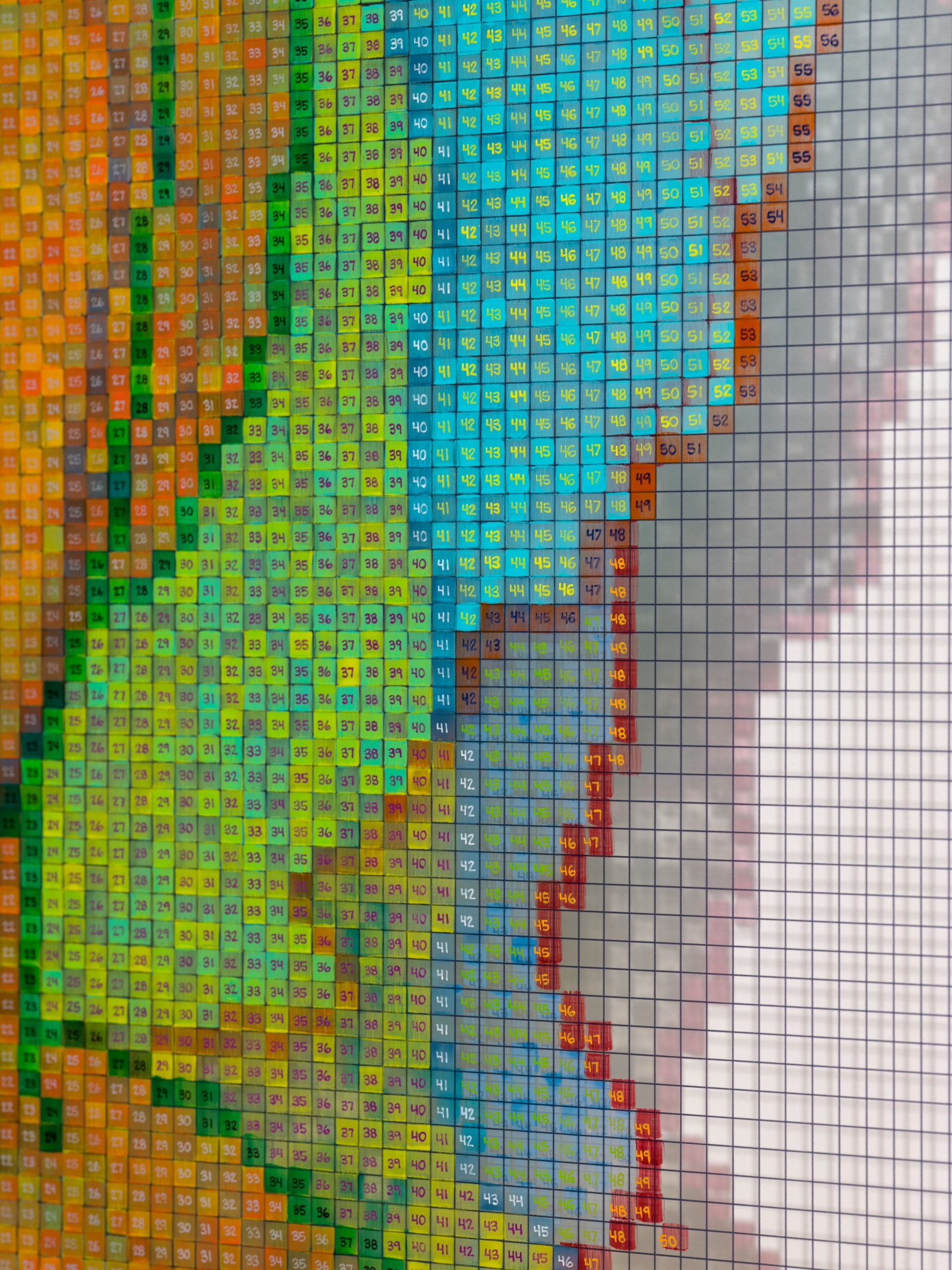

It was a curator at Hauser & Wirth in London, where the artist’s debut UK solo show is currently installed, who suggested he travel to Dorset to photograph for a new series. The resulting images form the basis of London Series 1. These large photographic works are overlaid with plexiglass grids that are meticulously painted according to Gaines’ unique numerical sequencing.

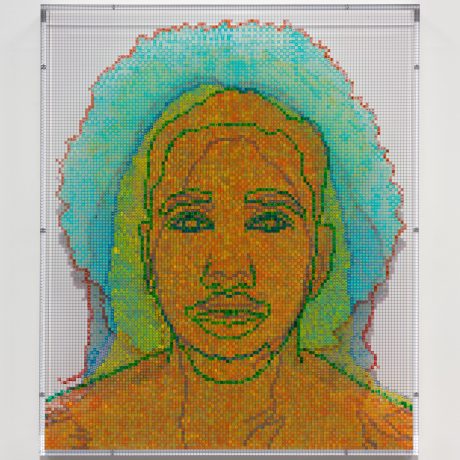

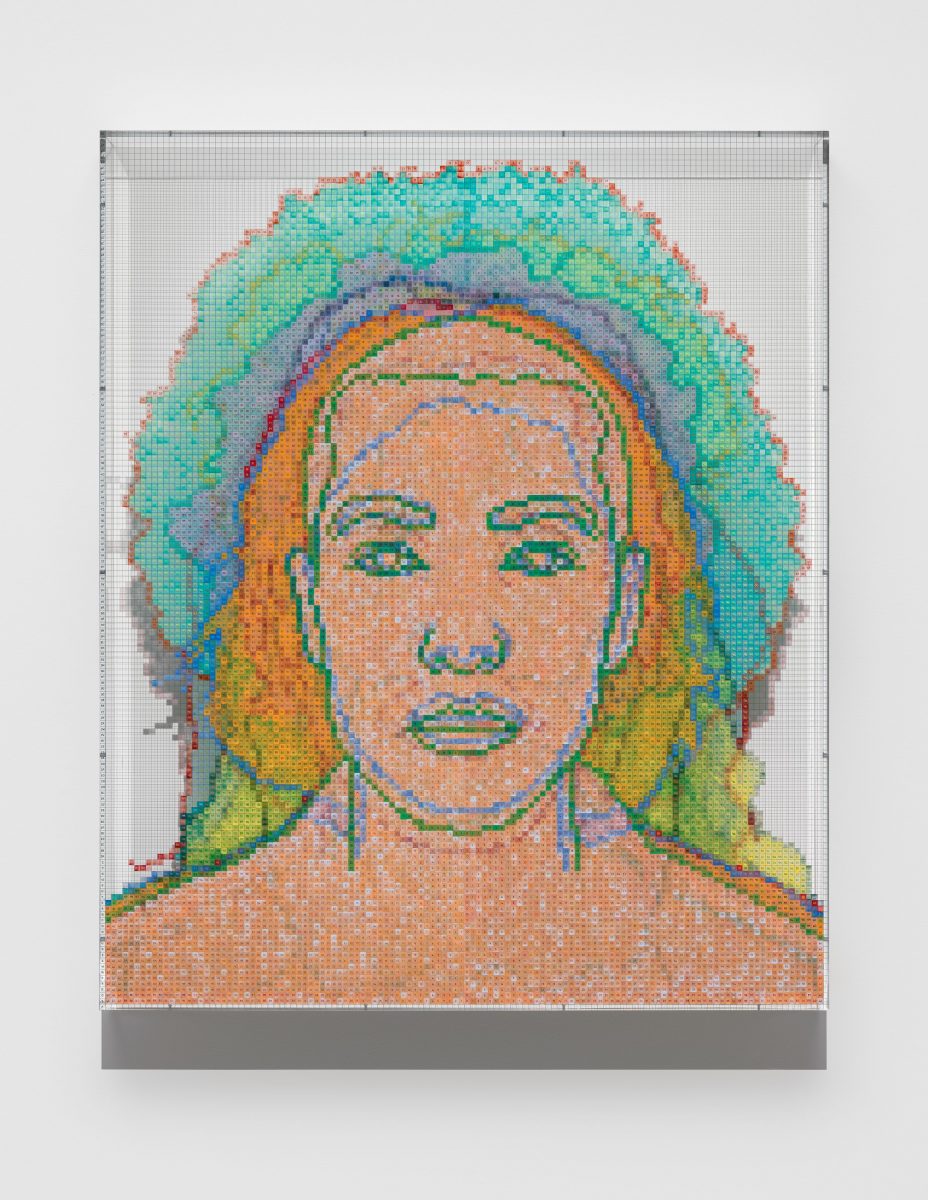

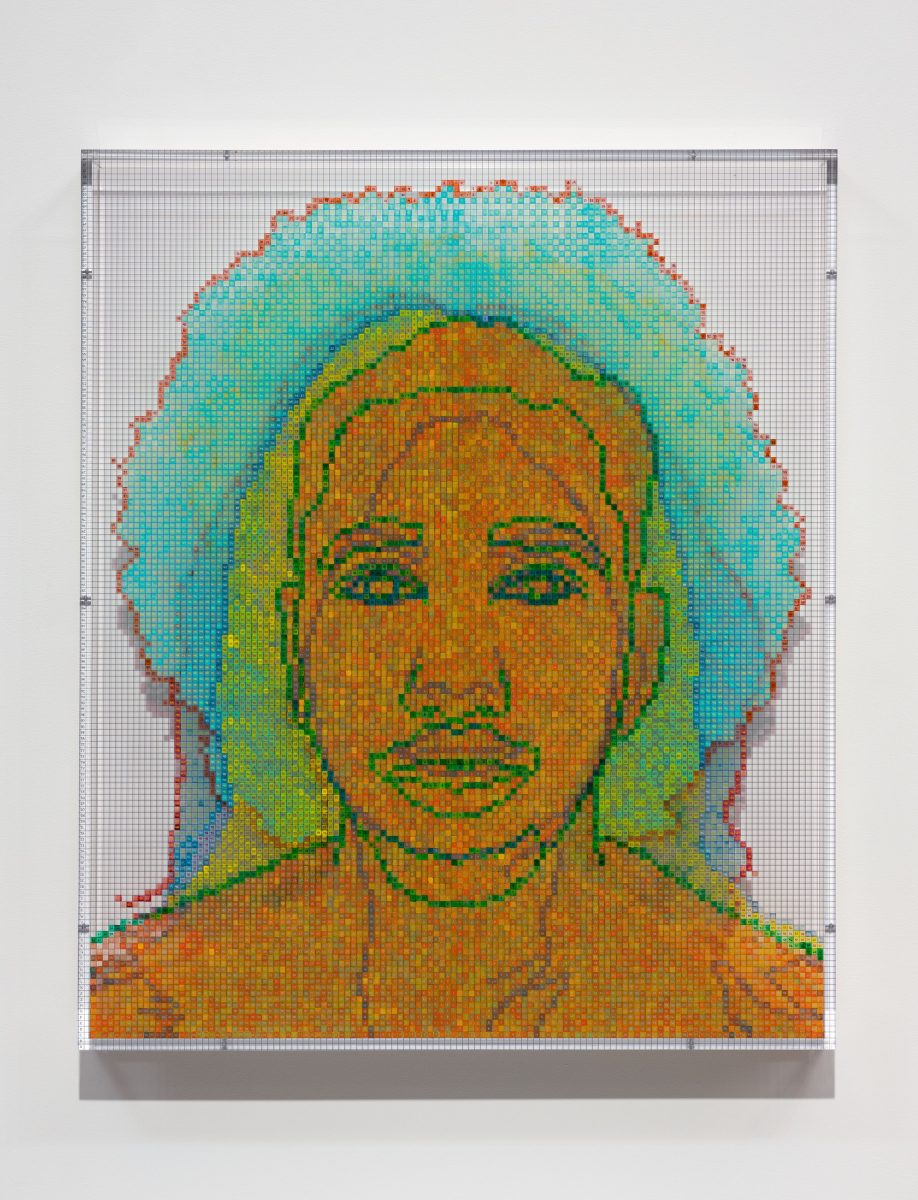

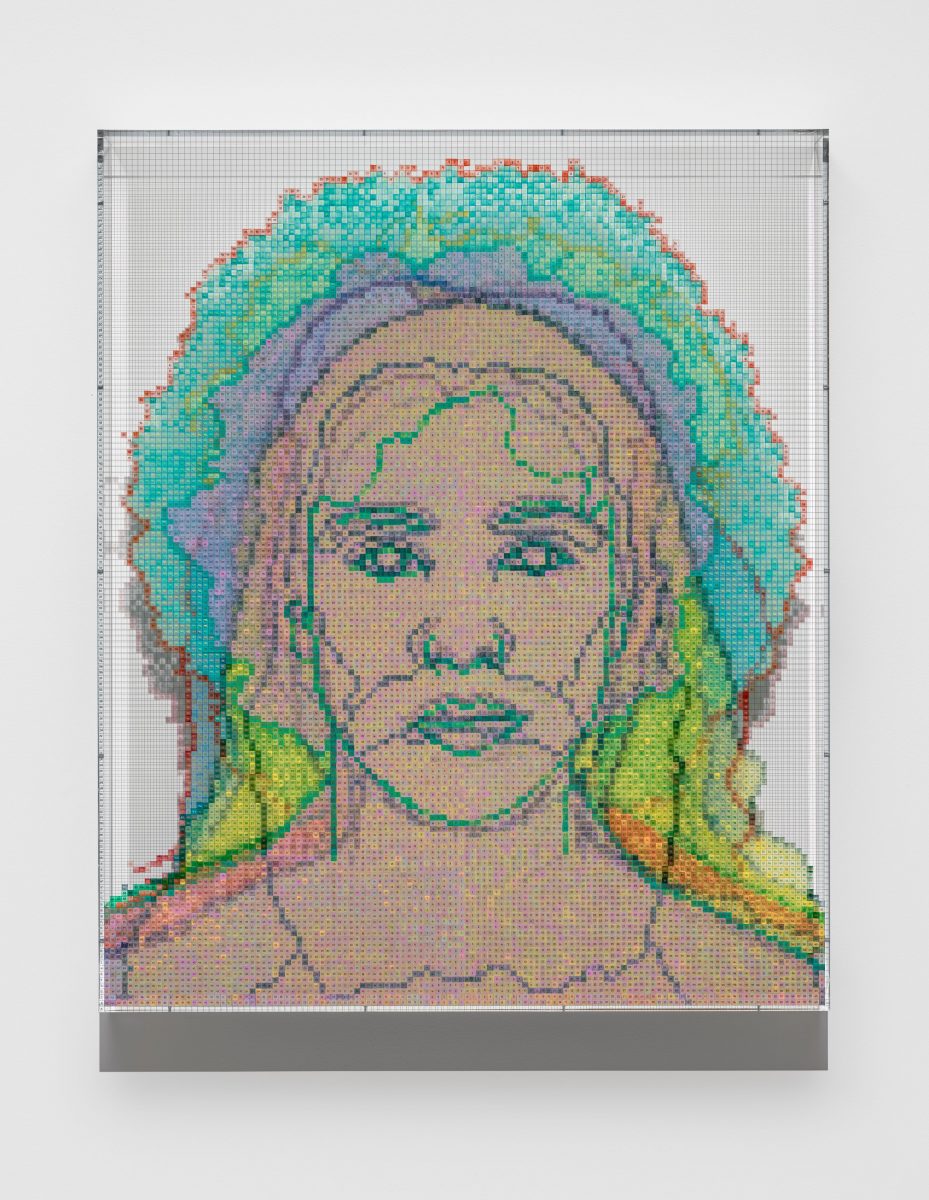

The same technique is used in the latest Faces series, which features photographs of mixed-raced people staring out from behind tinted windows. The works are hung like storyboards stretching across the walls of the gallery: each plexiglass front bears the painted pattern of its predecessors as well as that of its own photograph, creating a technicolour veneer while retaining each grid’s distinct pixelation.

The effect is “an analogy between mathematical layering and speciation” in both human and plants, Gaines explains. Building with colour means that in the later pieces the viewer must reposition along the work’s flank to see the photograph without its hovering palette. This space between subject and object is where meaning is constructed, says Gaines: the gap enclosed by two visual planes, like parallel lines which never meet.

“The grid is intended to keep the system present, so that you know that these decisions are not sentiments coming from me”

Gaines employs minor technical variations across different series. Although the positioning of his photographs (several inches behind the plexiglass) is consistent, his painted renderings differ in their relation to the background picture. For the oaks, for example, he developed a magnifying method in reverse, so the background photograph is an exploded image of the frontal painting. Despite these conscious variations, Gaines continues to describe the grid as a detached organising principle, which, along with strict colour selection, is “intended to keep the system present, so that you know that these decisions are not sentiments coming from me.”

Such formal discipline has come to define Gaines’ career, but his reluctance to wield creative agency offers a glimpse into a theoretical concern which goes far beyond his materials. His conceptual system becomes, he says, “a firewall between my subjectivity and the work,” alluding to a philosophical wrangling which manifests in, but is not resolved by, his art. The grid becomes a way of tracing Gaines’ theoretical development, absorbing and refracting his ideas on subjectivity and expression while retaining its internal order. Far from a firewall, it offers a rich insight into the artist’s process, and offers a wider comment on conceptual art’s ability to translate cultural and social themes.

Born in 1944 in segregated Charleston, South Carolina, the young Gaines’ frustrations found expression in philosophical, rather than political queries of American society. He began to question the belief systems and behavioural norms which allowed racial inequities to continue unchallenged. “I couldn’t understand why segregation existed,” he explains, “who made the rules and how and why those rules could survive and perpetuate, and how corrupt and immoral those rules were.”

Through this lens, he came to analyse the philosophical notion of universalism, the idea that there is a universal moral ethic which applies to all people, regardless of characteristic differences like race, gender or nationality, and which derives from the idea that universal truths exist. How could these beliefs be reconciled with the lived reality of segregation, with all its perverse ethnographic and social justifications?

“I couldn’t understand why segregation existed, who made the rules and how corrupt and immoral those rules were”

“Why do people think that the idea of subjectivity can be universal, when there’s such division and bifurcation in the world?” he asks. “I discovered that the notion of the universal was really a way for European theory to justify privileging some over others, and in an extended way to justify imperial and colonial practices.”

He was heavily influenced by the writings of Edward Said, particularly the Orientalism author’s use of Derridean theory to unpack cultural production and the postcolonial gaze. Instead of seeking to ‘deconstruct’ the idea of the subject within creative practice, Gaines followed Said in analysing structures of power as they existed in lived society, though he continued to position his work as critical rather than political.

As Gaines advanced his grid works and wider practice into the 1980s, his critique eventually came to address movements within contemporary art. His suspicion of the universality of subjectivity extended to Western modernism, whose treatment of representation he profoundly disagreed with. Developing his critique of universalism, he argued that the meaningfulness of an artwork is arbitrarily determined by what he describes as “the momentary terms and conditions of discourse: the movement of social and cultural ideas of a particular time,” rather than the artist’s vision or inherent truths. Creative decisions could be made without constituting a form of expression, a belief that deepened his commitment to systems in his own works.

It was around this time that Gaines underwent what he now terms his “awakening”, a realisation that his critique of subjectivity was motivated politically, rather than philosophically. “To be able to re-identify things as political was a huge awakening for me” he explains. “It went as far as me rethinking what I thought about myself as a human being: as a person and as a Black person.”

The grid system to which he had devoted so much philosophical attention began to speak to him as a political allegory, especially when overlaying his photography of faces. In reproducing the system for so long, Gaines had inadvertently endowed it with a neutralising function: whichever image sat behind the plexiglass (whether an oak tree or a non-white face), it would be translated and transcribed into the same rows of numbers and letters, irrespective of its original language.

“Why do people think that subjectivity can be universal when there’s such division in the world?”

In Multiples of Nature, Trees and Faces, differences between the photographs are flattened, reinforced by the inherent randomness of Gaines’ colour selection (despite the consistency throughout each series, there is no special reason why red is chosen for some portions of the face, and green others). When the painted patterns are placed on top of each other, the resulting hybrids become a comment on race, on the arbitrariness of racialisation and social stratification according to biological characteristics, and the implied instability of genealogy, hereditariness and mixed-race identity.

“If you’re layering the digital image, the analogy is that the cells of the digital image can be a corollary to biological cells,” Gaines says. “And if you embrace that reading, all of these theoretical models that frame the idea of arbitrariness are permitted. You can see how biological forms are themselves arbitrary in their production.”

His subjects for the latest iteration of Faces are mixed-race friends and acquaintances, a departure from an earlier series, Faces I: Identity Politics (2018), in which he used photographs of thinkers including Karl Marx, belle hooks, Karl Marx and Malcolm X. Gaines traced the lineage of an identity-based politics of the self, a defence against a resurgent American right intent on disempowering minorities by presenting identity politics as an attack on whiteness.

For someone initially resistant to politicising his grid works, the series was a significant intervention. Was it a one off, or can Multiples of Nature, Trees and Faces be seen as a newfound embrace of the political subject? Again, Gaines defers to the depersonalised nature of his system, a methodology which has, over time, come to direct the works more than he does. “I have no idea what the work is going to look like; how it’s going to work out,” he says. “I can’t just do a couple of sketches, I have to invest in work on some serious level and hope it works.”

Such conceptual faith speaks to the grid’s ability to evolve and reflect its surrounding conditions, an embodiment of Gaines’ belief that meaning is created by context, not decision. Its role is to reframe rather than transform the images behind it, and to complicate the perceptive codes around photographic representation, no matter if friends, philosophers, or plants are the chosen subject. “If you have an orchard, you have a cultural space that is driven by politics,” Gaines says. “Otherwise, you just have a forest.”

Charles Gaines, Multiples of Nature, Trees and Faces

At Hauser & Wirth London until 1 May

VISIT WEBSITE