Christian Boltanski sits in a sideroom of the Marian Goodman Gallery in Soho, sipping espresso and gesturing towards a work hanging on the opposite wall. “I love this painting, but we can say it is a painting […] because we are in a gallery.”

It is the afternoon before the opening of Éphémères, Boltanski’s first solo show in London for eight years, and the French artist is in irreverent form––simply creating objects to hang in galleries, you sense, leaves him cold. “I don’t like so much to show in a gallery,” he explains. “What I try to do is [make] people forget totally about that. They are somewhere, but they are no longer in a gallery or a museum.”

Entering Éphémères means passing through a veil––a sheet of fabric draped over the entrance, printed with a photograph from a 1950s family album, the figures now faded and indistinct. Beyond that point, the white-walled gallery has been transformed into a dreamlike space, the air thick with chiming bells and sharp with the scent of fresh hay. Navigating the exhibition––pushing through the hanging images that continue along the central corridor, ducking past the dim, low-hanging lightbulbs––is a strikingly physical experience.

“It sounds pretentious, but I try for l’art total,” says Boltanski. “When I made Personnes at the Grand Palais, I asked to cut the heat. It was January, and everybody had a coat because it was so cold. And there was something on the floor, so that people must walk like this”––he mimes a visitor treading carefully, as if stepping around broken glass––“and they were part of the piece. For me it is very different to be in front of a piece than to be inside it. And in my case, I’d rather people are inside.”

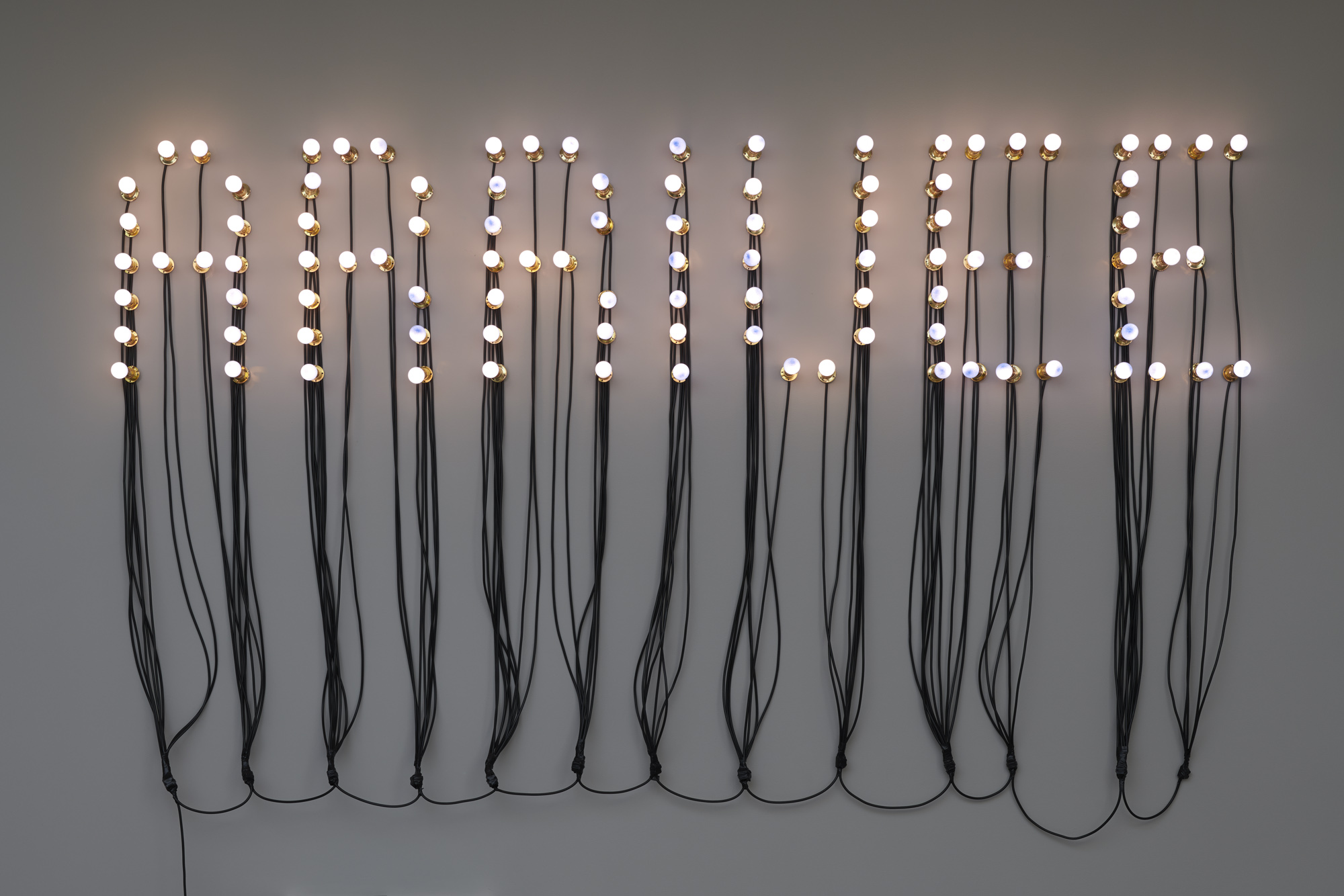

Bookending the central corridor are two pieces that have become a Boltanski trademark: above the entrance red lights spell out “départ” while, at the stairwell at the far side of the room, “arrivée” is illuminated in blue. The words are partly a tribute to the director Alain Resnais, a favourite of the artist, who had planned a film titled Départ Arrivée before his death. But more significantly within Boltanski’s art, departure and arrival are synonymous with birth and death. “Life is départ and arrivée. For me, a show must be a journey, and at the same time it is our life. There is départ, and we walk a little, and there is arrivée.”

While death continues to be a presence in the newer pieces that comprise Éphémères, the fatalistic outlook of Boltanski’s earlier works has been replaced by something more meditative. Where once he would have used a photograph or personal effects to represent the dead, here their presence is felt, rather than seen.“Some of my works are rather sad, but this one is more quiet. It is, in a way, after. Because it’s after the fact of dying.” As the seventy-three-year-old’s thoughts have turned to his own mortality, his practice has shifted away from documenting death and towards creating something that will transcend it. “At my age, it’s normal to think about my disappearance, my absence. These pieces are not to create something about me, but to create a mythology––to be present but also to be outside.”

“All my life I asked the big questions about life and nobody could answer me […] So, at the last minute I asked the whales.”

Here, Boltanski refers to the two works from his Animitas series that flank the exhibition’s main corridor. Taking its name fom the roadside memorials to the dead that line Chile’s roads, the series saw the artist travelling to deserted regions to install hundreds of small Japanese bells on long stems, arranged to reproduce a map of the constellations on the night the artist was born––a delicate act of self-mythologizing that binds his story to the landscape and the stars.

Films of the installations in Chile and Canada are projected onto the gallery walls, the sound of the wind blending with the ringing of the bells, each chime a departed soul. For Boltanski this is a space for contemplation, surrounded by the presence of the dead. “You have the little bells in the Atacama Desert and Quebec––the small souls. I believe there are a lot of small souls all around us. I’m not religious at all, but we can say this piece is… not a paradise or inferno, just somewhere a little lost. We are lost, and it is not sad––it is only a place to wait.”

Éphémères (Mayflies), 2018

Further through the gallery, a door opens to a sideroom hosting the installation that gives the exhibition its name: Éphémères. “They are these little insects that live only a few hours,”says Boltanski of the title. “And for me this is an image of us. They are for a long time in the water, and then they have three, four, five hours to live. And they die, they make sex, and that’s all. And that’s what we do in life.” Installed in a black room, unlit except for the footage of swarming mayflies projected against strips of fabric hanging ceiling to floor, it is typical of the artist’s late style: art as a physical space, embedded in nature, humanity implied but absent.

Boltanski speaks of his recent works exploring what comes after death and, continuing through the gallery beyond the arrivée that denotes the end of the exhibition and of life, there is a further piece. You hear it before you see it: a low, metallic moan reverberates intermittently.

Climbing the stairwell at the end of the central corridor, a triptych film installation comes into sight, filling three walls that meet at a shallow angle. On the right: an unbroken view of the Patagonian sea, the scene only disturbed by the occasional flight of a petrel. To the left: the skeleton of a whale, its ribs splayed over arid coastal ground. And in the center, the heart of the piece: three towering black forms mounted on poles atop a promontory overlooking the ocean, each bow-tie in profile and finned at one end.

The piece is Misterios––a 2017 installation that saw Boltanski install three monolithic trumpets in an uninhabited region on the Patagonian coast. Working with an acoustician, he tuned the instruments to mimic whale song when the wind passed through them. “All my life I asked the big questions about life and nobody could answer me. In Indian culture, whales are the animals who know the beginning of time. So, at the last minute I asked the whales.”

Like the bells of Animitas, the trumpets of Misterios will eventually be erased by the same wind that animates them; the guttural sound they create is closer to a death cry than whale song. But for Boltanski, the survival of the piece––and of his role in creating it––is less important than the myths he hopes to inspire.

“I believe that mythology is stronger than the art piece. I hope that in a few years the piece will be destroyed, and everybody is going to forget my name. But people will say there was a crazy guy who tried to speak with the whales.”