Just hearing the title of Christian Lagata’s new book, Up Around the Bend, may cause in some a sudden onset of earworm. It was just three years after the release of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s instant classic of the same name that Lagata’s family moved into the municipality of Rota in Cádiz, and into the passive influence of a US military base leaking its culture through its ubiquitous fences and barriers.

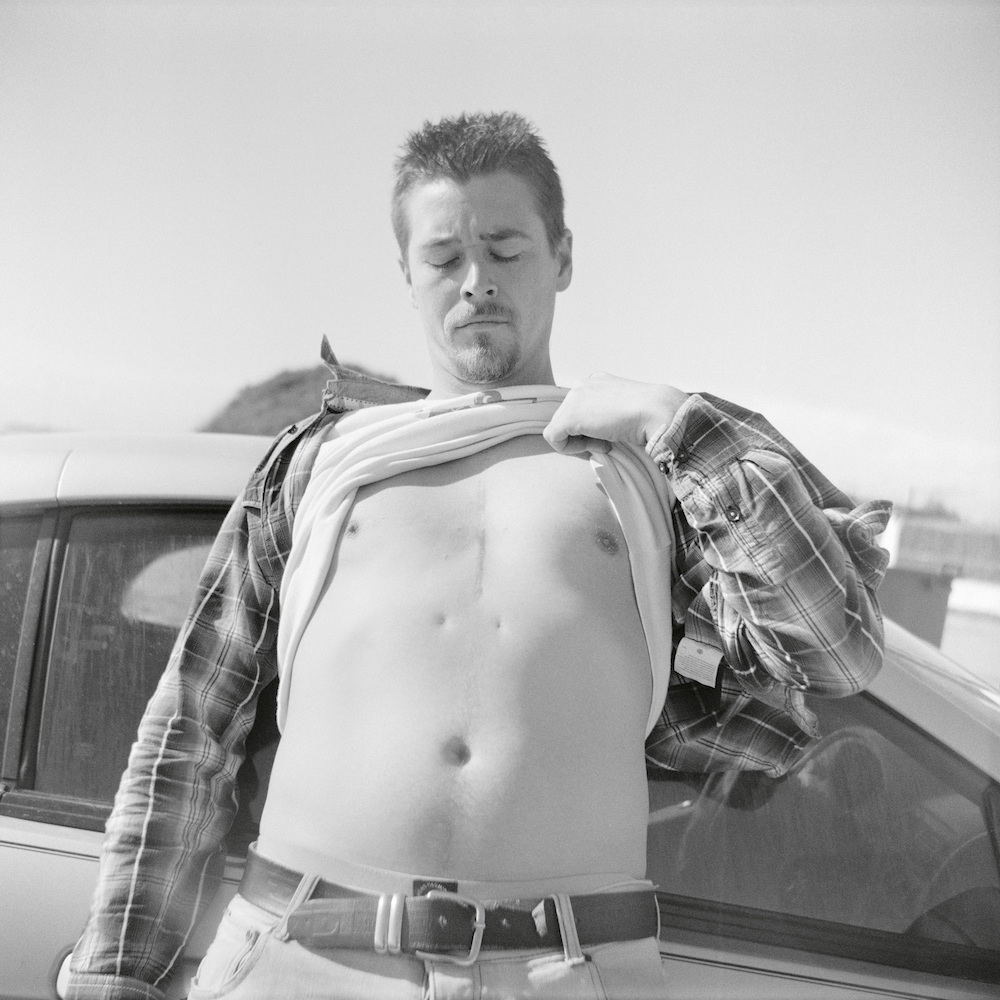

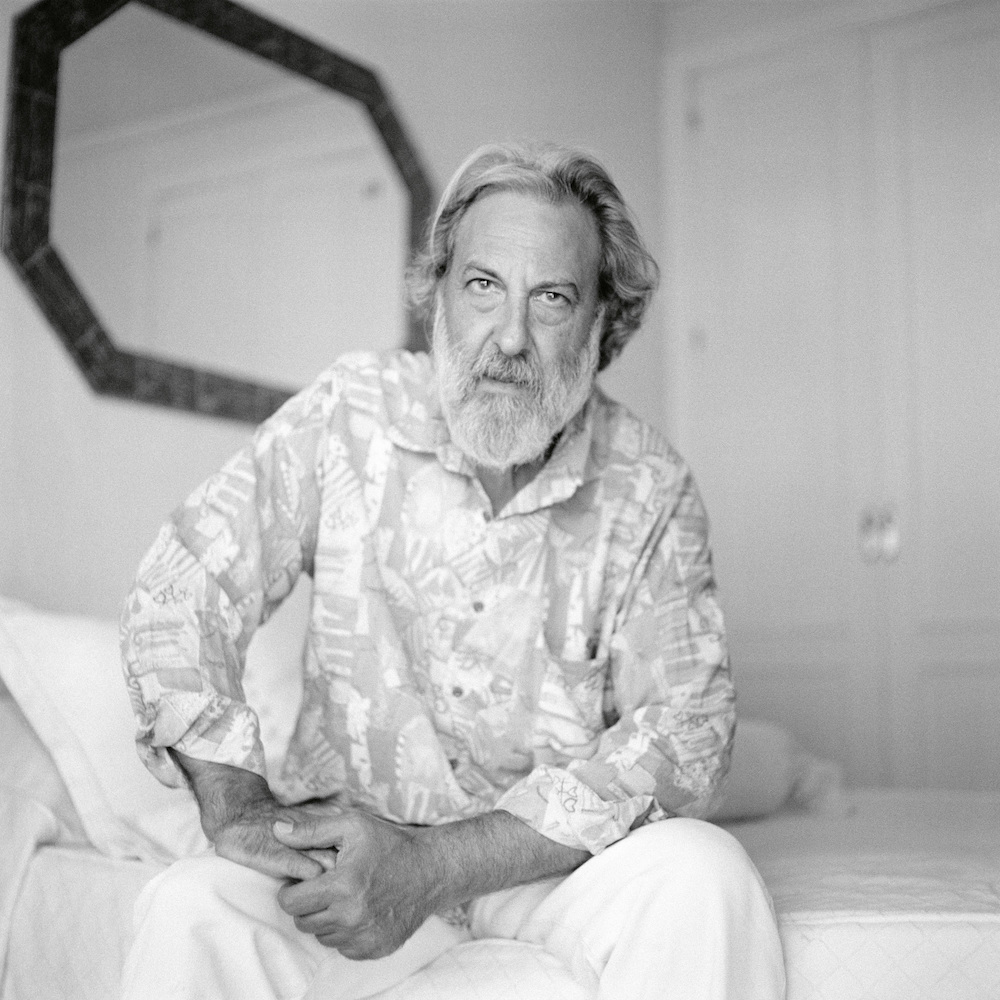

Some 38 years later Christian Lagata began ‘to observe and to look around the gaps of the fence, which let the North American culture and traditions spread across the communities, trying to make sense of his roots and his life’. The resulting book features quiet, observant black-and-white images from the communities Lagata himself identifies with, interrupted occasionally by low-resolution colour archival images of things like a tightrope walker and an elegiac man in a Ghillie suit; all scenes and ‘things’ contributory to Lagata’s thoughts and memories of the communities he grew up around.

‘[T]he images taken around the fence have this weight and this slowness that invite us to read them one by one, almost as milestones. Landscapes and above all portraits, are important to understand the whole project. They tell a story, they became signs and signals that solve, in a way, certain doubts of the project.’

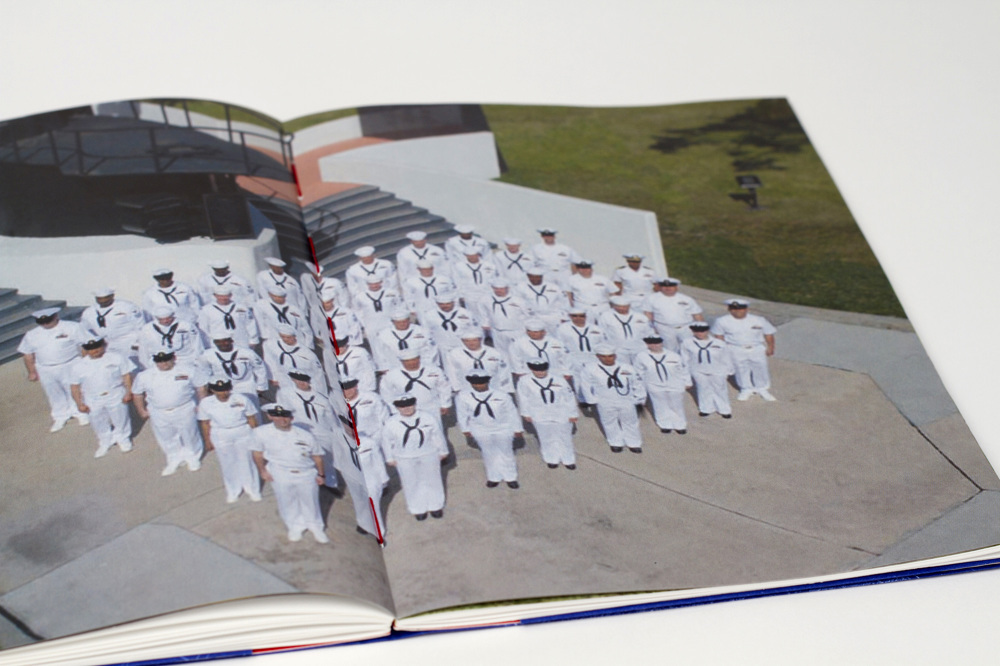

This sequence is then punctuated by a section of images gleaned from websites, both personal and official, of the inside of the military base. From a cluster of almost exclusively Caucasian hands to images of training drills to a pseudo-Iwo Jima flag raising, this kind of inner pamphlet of low-resolution, hazy and enigmatic images provide clues as to what may or may not be on the other side. The sense of pensive distrust is strong here, but not in the commonplace satirical critique style. It appears more as a genuine unease about the motivations of those behind the images.

‘I am fully aware that those pictures are carefully selected by American authorities, composed to sell some kind of unreal happiness and fake wellbeing. I try to take advantage of this fact by choosing images in which this duality is shown, and by repurposing them to speak about my own reality. I take their “happiness”, their dirtiness and the air of mistrust around them in order to close my own circle, my own design.’

The calm, orderly and precisely sequenced images are, with melodic repetition, cut in half by the bright red thread that binds the work together and bookended with bright red cover and end pages. This red and white book is then completed by its blueprint map of Rota, concreting the work as both topographical study and complex exploration of memory and identity.

Ollie Gapper talks to Christian Lagata.

OG: I’d like to ask about the title of the book. For someone from the UK, a country that has had massive cultural influence from the US, it brings to mind the lyrics and melody of the Creedence Clearwater Revival song of the same name. Was this a conscious effort to align the audience with your own perspective of being under the influence of North American culture?

CL: It´s just like that. The title is very important for me. People who know the band and the song are immediately aware of a context and a scene: the 70s, rock and roll, USA and all the things associated. The root of the project is showcasing a reality in which I don´t really belong, and it takes place in a town in the south of Spain heavily influenced from the beginning by a really strong foreign culture. My own travels start there, the travels with my American friends around the fence, listening to Creedence, starting to be aware of two realities at once. Understanding that these influences go back to my very beginning, thanks to my parents and their passion for the music and all of those things.

OG: It’s interesting here that you give thanks to your parents’ passion for music, even though you feel the influence of North American culture has confused your sense of cultural identity. Would you say, on the whole, you are happy to have grown up in Rota or do you feel you were short-changed in some way by the presence of the base?

CL: It´s not easy to answer that question without contradicting myself. I feel proud to have been raised in the south of Spain, in a wonderful place that’s home to many rich traditions, such as flamenco. The base is a military base, and that aspect is one I´m not very fond of, but on the other hand, the constant influx of American people, some parts of their culture like the music and all the great bands, are definitely positive for me. This particular mix of influences is awesome and unique.

OG: What was your motivation for using other people’s images of the interior of the base? Was it purely due to access limitations or to help better convey a sense of dislocation and distrust?

CL: From early on, I realized that the cell phone of my American friend could be some kind of ‘key’ for entering the base. Using images from the net, especially those that could have a double reading while speaking of my close environment and dialoguing with my own pictures, is very powerful and it helps with the concept of the whole project. I am very interested in post-photography, its friction with classical photography, the importance of the net as a double-edged sword and the new ideas that are rising as a consequence.

OG: The images you have taken yourself seem to be quiet, calm, deadpan. The other imagery is pretty antithetical to this, being loud, close and unsettling—together I think they constitute perfect examples of the ‘time exposure’ and ‘snapshot’ as proposed by Thierry de Duve, who describes the time exposure as typified in the funerary portrait: ‘It protracts onstage a life that has stopped offstage.’ The snapshot, by contrast, ‘freezes onstage the course of life that goes on outside’. Would you say the images you have taken of the wall and communities surrounding the base are ‘funerary’? Equally, do you see the base as a kind of ongoing event?

CL: It´s true, the images taken around the fence have this weight and this slowness that invite us to read them one by one, almost as milestones. Landscapes, and above all portraits, are important to understand the whole project. They tell a story: they became signs and signals that solve, in a way, certain doubts of the project. The archival imagery has another rhythm and another texture, and it uses completely opposite codes. Two different languages that put together enrich the whole plot. I am always thinking as a songwriter: the black-and-white images are a slow tune, well produced like a folk song and the colour images add the rhythm and the noise that make you move, making the final mix greater than the sum of the separate parts.

OG: Could this then be seen as two different attitudes to the two spaces portrayed? Linking back to Creedence, one might consider songs like ‘Travellin’ Band’ and ‘Fortunate Son’ as the rhythm and noise that agitate and call for action, whereas songs like ‘Have You Ever Seen the Rain?’ and ‘Long As I Can See The Light’ are the slow tunes, the black-and-white images that invite reflection rather than action.

CL: The black-and-white images have been created from silence, by seeking inside me, trying to stop time and choosing images that I find helpful to understand what is beneath the surface. These images are a mirror of myself and hopefully also a mirror of other people. In order to help to create the work, I usually use music to create a specific mood, to help me understand what I am trying to tell. In this particular case I listened to people like Karen Dalton, Jackson C. Frank and Jason Molina. I feel they work in that blurry line that separates cry, lament and whisper.

OG: It was Steve Edwards who wrote: ‘we doubt less the images than the motivations of the persons who put this into place.’ I feel a genuine sense of distrust towards the images of American military bases. The section appears as selective moments from public events aimed at gaining favour in the eyes of those attending; selective moments typifying the happiness and wellbeing of all those portrayed. You have quite distinctly used lower-resolution files for this section, covering the images in a net of technical imperfection—making ‘things’ of them, as Bill Brown might say. Is this sense of distrust intended to echo a more general one felt about the base?

CL: I am fully aware that those pictures are carefully selected by the American authorities, composed to sell some kind of unreal happiness and fake wellbeing. I try to take advantage of this fact by choosing images in which this duality is shown, and by repurposing them to speak about my own reality. I take their ‘happiness’, their dirtiness and the air of mistrust around them in order to close my own circle, my own design. The whole project is full of that lack of clarity and of that struggle between two conflicting realities, with myself right at the centre of it.

It´s funny that you mention Bill Brown. Up Around the Bend is a photobook but also an installation. In the installation there is an audiovisual piece in which I circle the whole base with my car. In a way, I feel that the piece and the rest of the project are related to great authors like Bill, Jim Jarmusch and Wim Wenders, and that dirtiness binds the whole project together.

OG: What were your influences/motivations in the physical design of your book?

CL: From the beginning the importance of the interplay generated between the dust jacket and the subsequent revelation of the title in the cover was very clear to me. I always thought of it like something akin to a child’s game, like a map where you had to find something.

The design of the title was intended to evoke a danger sign and a music poster at the same time. Working with a designer was really important to iron out this kind of detail: finally we decided on the aesthetic of the danger sign combined with a map that brought to mind the blueprints of the 50s, giving a nod to the base’s origins.