“I am in paradise. Paradise is unbearable.” Christopher Williams nears the end of his exhibition at Corbett vs. Dempsey and is soon to open a solo show at David Zwirner, London.

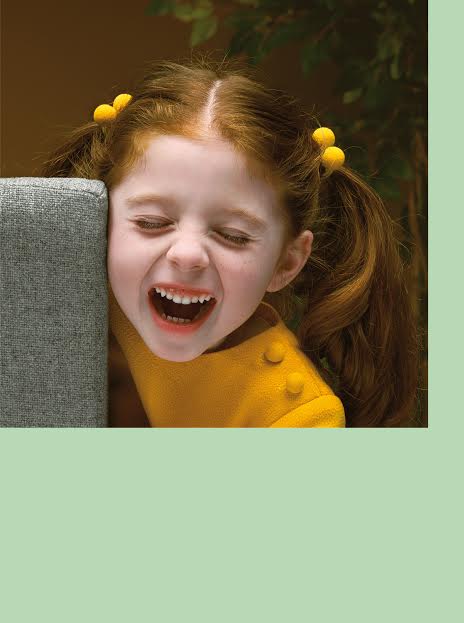

Girl: Age 5-6. Skin: milk white, pale rose flush. Naturally stained lips (the edges are a soft coral tint), copper hair, split in the middle to reveal a white parted line, pulled into pigtails, each fastened by a set of bright golden bobbles that match the two circular buttons on her pollen yellow shirt (6 round objects in total). Baby teeth, perfectly spaced, frame the hollow opening of her mouth, which shares the same dark tone as the blurred backdrop. Her cheek kisses the edge of a neatly upholstered grey, modernist piece of furniture. Laughter without sound, an inaudible wincing grin. She shutters her eyes from you.

The action: she shutters her eyes from you.

The instant: the camera shutters, and so do her eyes.

This image is placed upon the margins of a field of pastel green, the hue of stock printing paper—an impartial backdrop, though the filmic quality of the photograph suggests the modular potential of its placement. The green screen, as if it were keyed into the final composition. Any emotional description of the image registers as effusive and incorrect; the outset of terms such as ‘innocence,’ ‘joy,’ or ‘giddiness’ miscalculate the contempt toward the boundless perversion of the modern image. The false pursuit for the immobile tenderness of girlhood slips away—we can read the image as the child, green and golden—to expose the propaganda of purity that accompanies commercial photography overall. In its place arises a distortion, the unattainable emerald city. The insistence that the illusion of twentieth century stylistic nostalgia has been defeated by familiarity is so quietly proposed, it risks being mistaken for the thing itself. It is with this sentiment we encounter the girl, Untitled (2017), suspended within the same faint serpent green that envelops Christopher Williams’ current exhibition, Supplements, Models, Prototypes, on view at Corbett vs. Dempsey.

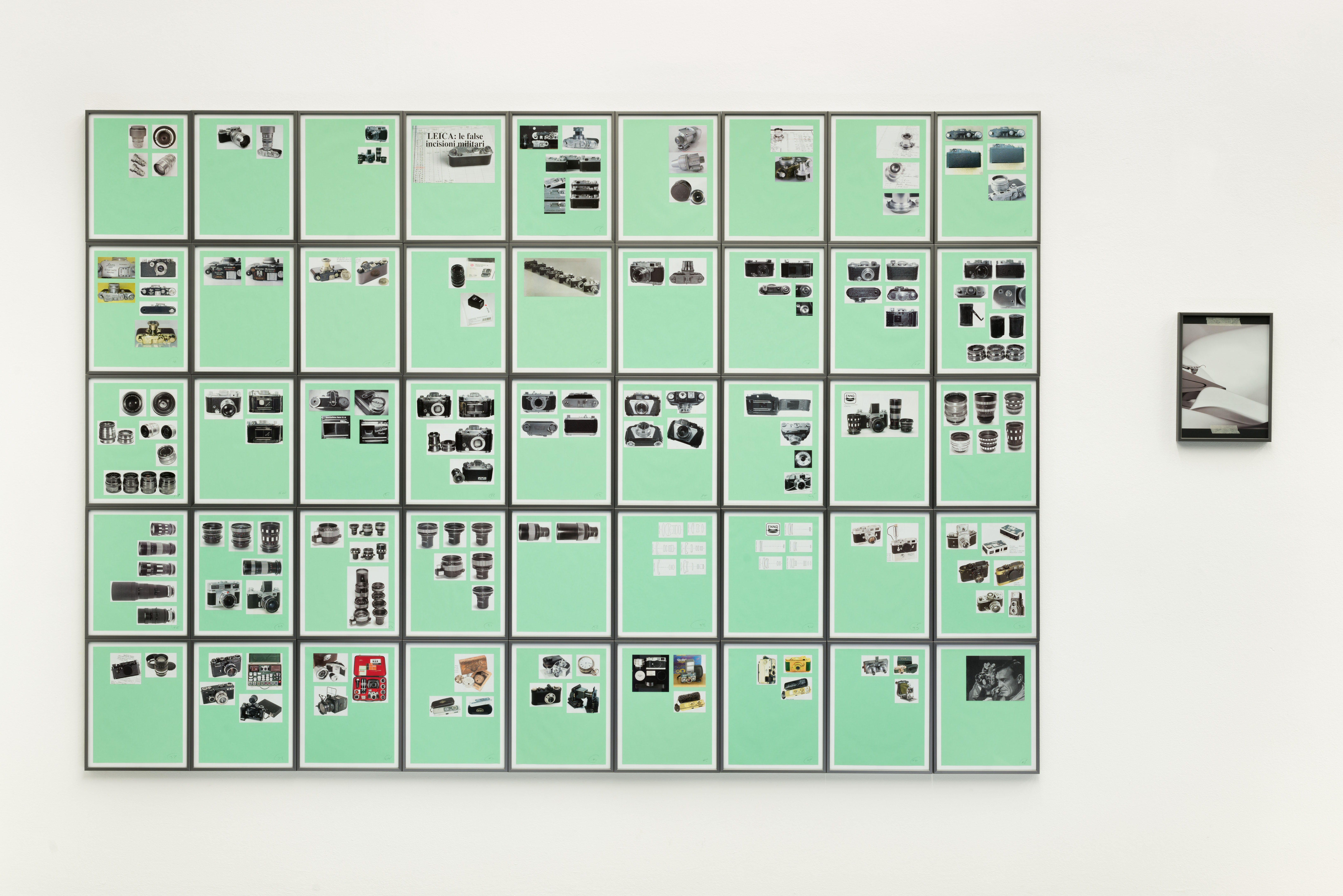

The girl is installed at the edge of the ceiling, one of six images in a succession of aluminum frames—next to her is a historical Linhof camera 13 x 18 film holder, a free-standing wall structure on a low pedestal base, a bright white chicken profiled against a baby blue backdrop, a shallow pot submerged halfway in transparent water, and a dissected camera, sliced down the centre. Each of the compositions echo Williams’s ability to capture the ‘action’ and the ‘instant’ of the image—the dual register of the photograph, and the technical apparatus that created it. This double identification extends to the exhibition design—the large-scale prints are obscured by the structure of a transposed wall, which functions as the central support in the gallery. Slightly battered and purposefully incomplete, the open and partially unfinished edges of the two-tiered barrier reveal the wooden struts holding it together. On one face of the divider, a series of collage works are installed in a grid, each adhering to the same basic principle: cut-out catalogue reproductions of cameras pasted onto the surface of framed 8.5 x 11-inch sheets of acid-free bond paper (the original source of the green tone, replicated as a formal motif in the larger prints). The collages, a central component of the exhibition, have remained an unchanging part of Williams’s practice since the 1980s, though this is the first time the full series has been exhibited in the United States.

In all bodies of work—the large poster prints, structural wall intervention, and collaged grids—the colour green is transformed into a symbol of elsewhere. The gallery space itself is not immune to this tactic, as the repetitive hue subtly engulfs the entire exhibition apparatus into its fracture. Like an overgrown species, the colour crops up on often hidden or unnoticeable edges of the gallery walls, just as the supporting promotional texts for the show are printed on the same stock as the collage works, which is also bound in the primarily blank pages of the catalogue. Its reappearance as a device resists immersion of the viewer, forming instead the impossibility of falling into a frameless plane—or, as Williams writes in an open letter text accompanying the exhibition: “To create a place that, like the present, does not exist.” While the works themselves carry an otherwise anachronistic aesthetic, approaching the status of a nostalgic replica, the tenacity of Williams’s mid-century style is matched only by the resistance of its descriptive placement—not because the image is uncertain or undecided, but because it is so precise that to describe the image is to destroy it. As the first line of the open letter for Supplements, Models, Prototypes asks: “How is it that we turn to the studio now?” For Williams, staging the death of the image has been professionalized. After all, what more is death than a marketable cycle of expiry, exhaustion, and renewal?

If the modern image is the agent of the spectacle, then Williams, its silent Director, casts twenty-first-century photography in a supporting role—not as the singular trained actor, but the plural stunt doubles, fill-ins, fringe extras. The lead characters of mid-century archetypes recede into the stage wings; Williams captures the understudies performing their isolated and fragmentary actions to the camera. As the continuum of the modern image approaches exhaustion, Williams questions what more, in its counterfeit state, is left to forfeit. While the purity of mid-century representation may have ever only existed as myth—its own green promise not unlike the ideal of the emerald city—who will concede its image now that illusion has become the material of the message? Remember that Surrender Dorothy was written in the clouds without a comma—to address society, not the individual.

‘Christopher Williams: Supplements, Models, Prototypes’ runs until 11 March at Corbett vs. Dempsey. Christopher Williams. ‘Open Letter: The Family Drama Refunctioned? (From the Point of View of Production)’ runs from 17 March until 20 May at David Zwirner, London. Images: Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne. Photos by EPW Studio/Maris Hutchinson, 2017.