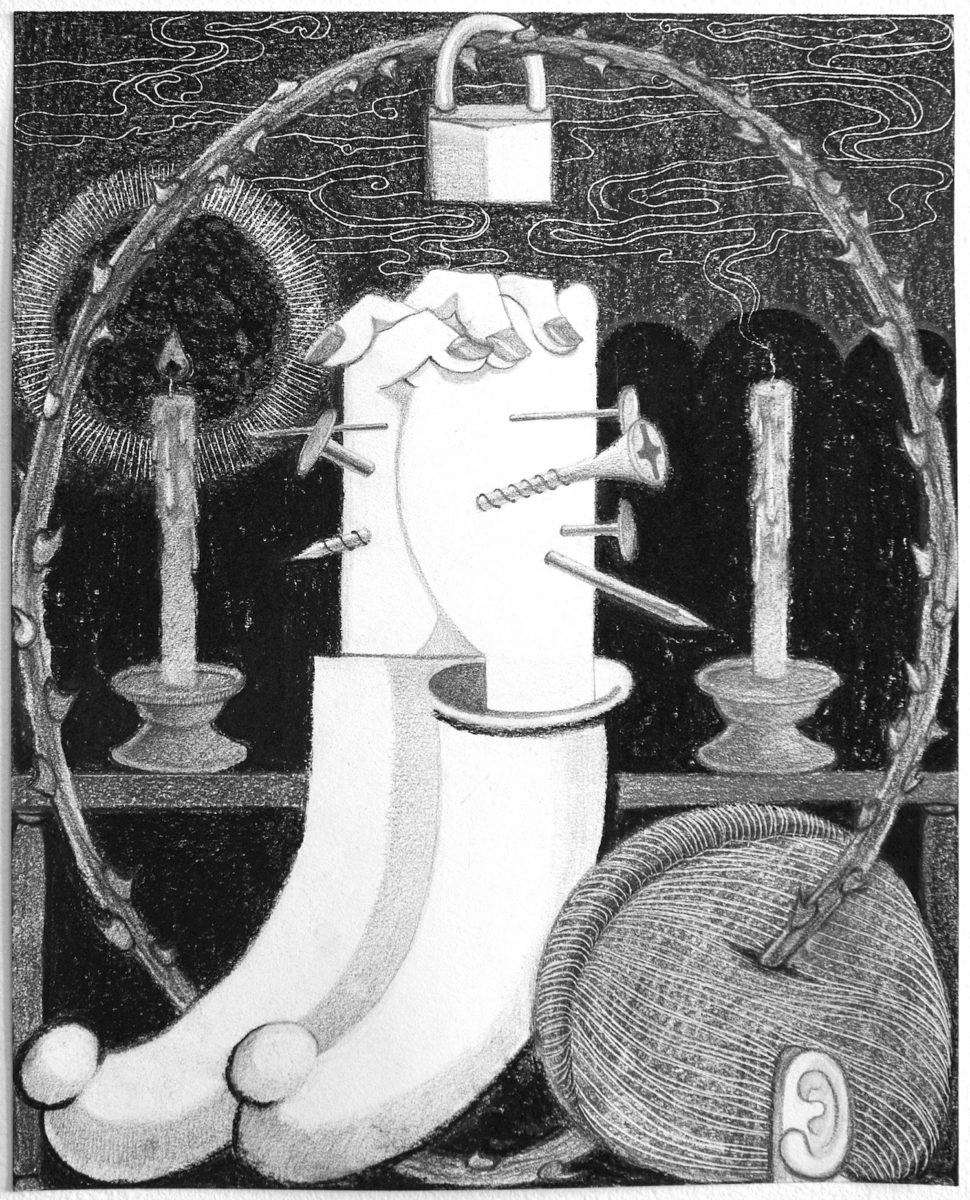

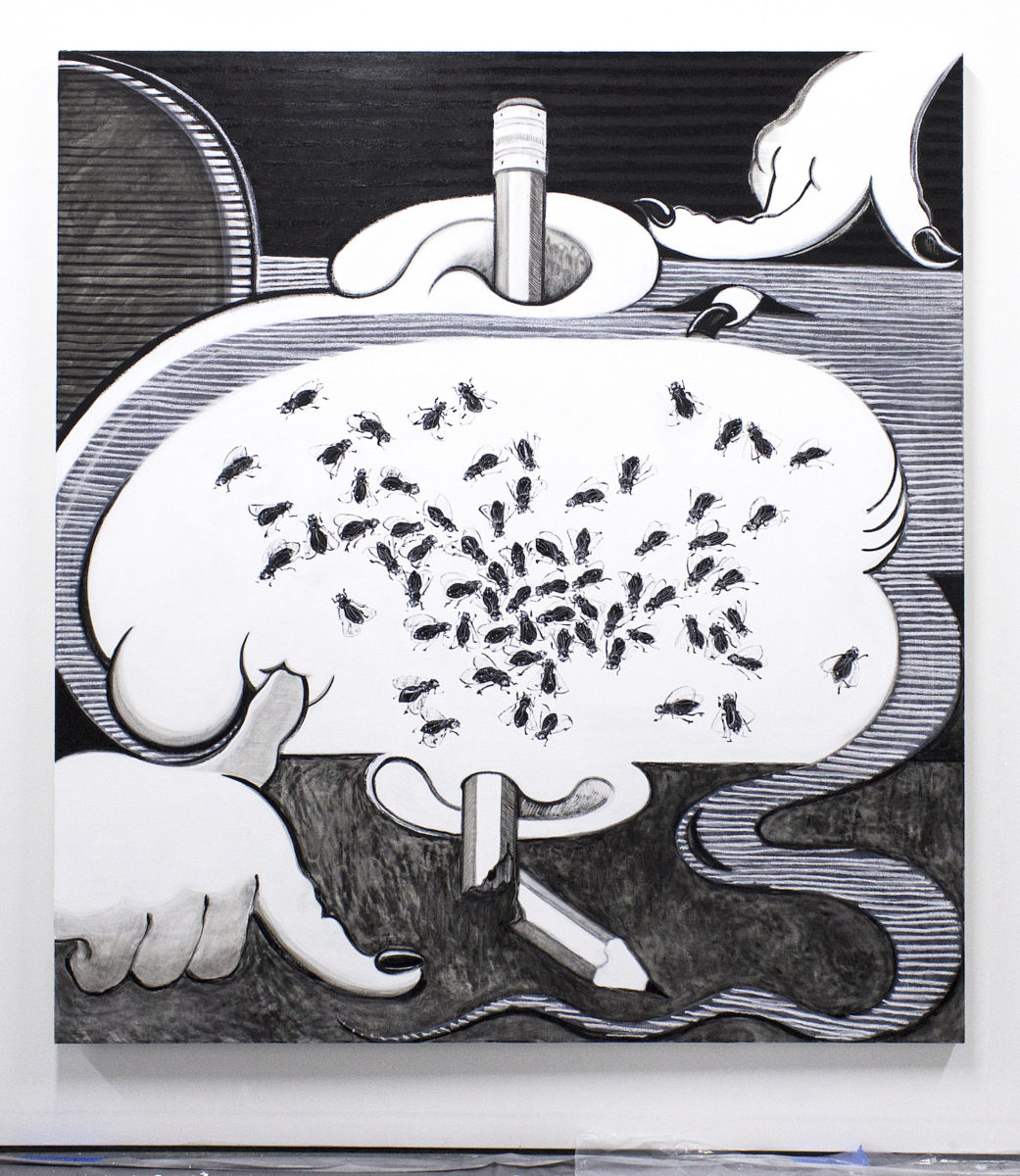

You encounter a gruesome scene, perhaps a part-decomposed body alive with flies, rats and other rodents; a knife lies to the side. You’re not meant to be there, but you can’t stop looking. How long before you avert your eyes? Canadian-Korean artist Cindy Ji Hye Kim explores the surprising extremes of our tolerance for shock and disgust in paintings that place us as voyeurs in an unknown narrative. These are images that feel closer to snapshots of an ongoing scene, a single frame within her own distinctive horror movie.

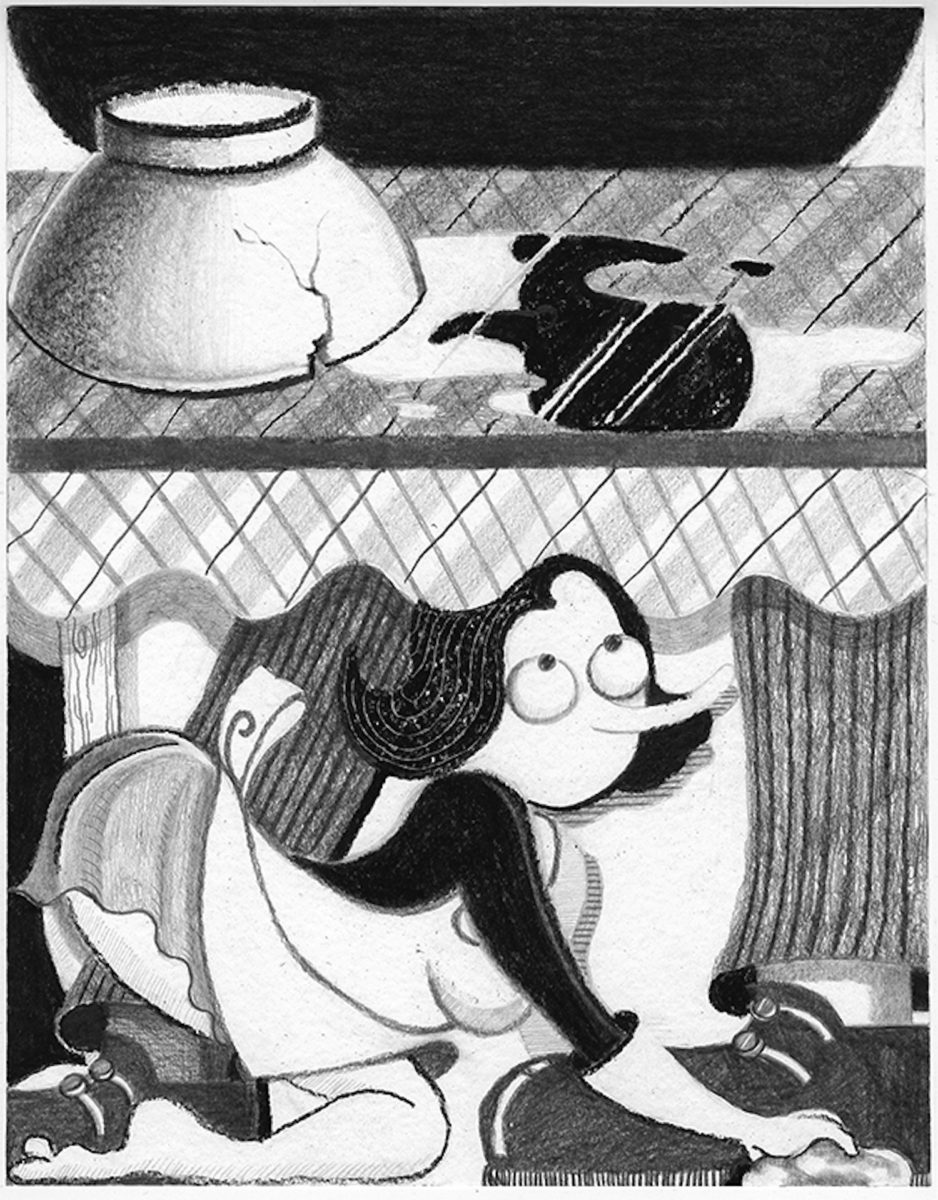

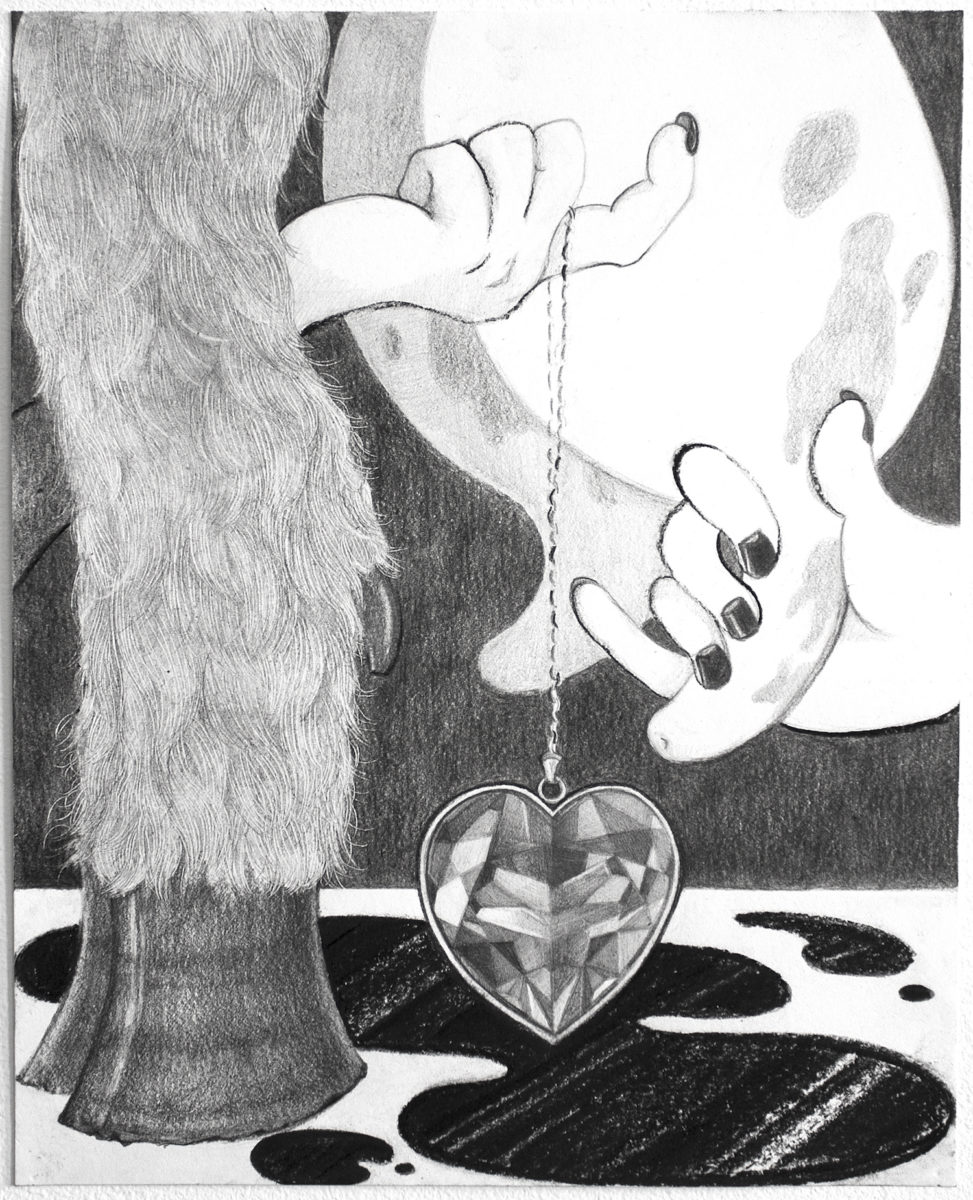

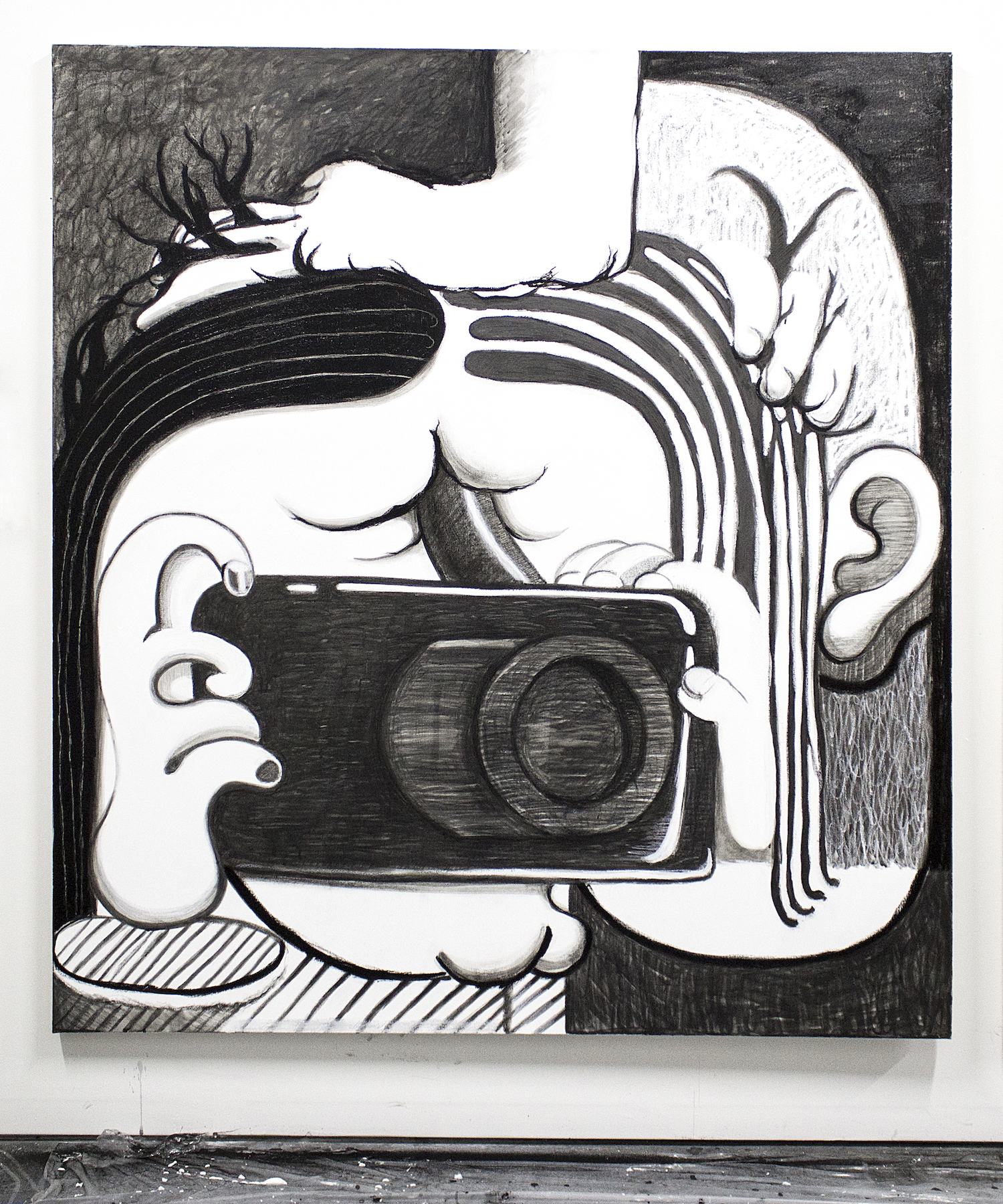

Look closer, and familiar household items come into view. Kitchen scissors, rubber gloves, a mop… turned into instruments of violence, they take on new significance. The home might be where the heart is, but here the heart is staked out and stabbed to death. Female bodies are dominated by their tools of domesticity, sexualized even as they are subsumed. And yet, the scenes that Kim dreams up remain palatable, even playful, rendered in graphic black and white. It is a style rooted in the legacy of cartooning, whereby even the most horrifying of occurrences can be made digestible, holding your gaze just when you think you can’t take any more…

The female body is a recurring subject in your work, with often only a section revealed. Cut up or disembodied, the body is put to both humorous and violent effect. What does the female body mean to you in the context of your work, and how do you approach it?

Overall I’m always attracted to the generic and the ubiquitous—the less specific the better. When it comes to the female form, it’s about playing with the existing archetypes that I find are most efficient. These are often overtly pornographic or helpless: the two forms of femininity that in mass media or even in novels or films I find to be generally ubiquitous. There’s this duality that governs femininity in our culture which I find really interesting to work with. I see myself as an image-maker, and I become almost the police officer who regulates how the female body should be depicted because—as much as I say I like the generic—I am constantly adding and subtracting.

The female form is such a politicized subject. I recently had a show in Toronto, and at the reception there was a guy who came up to me and told me that I was “brave”. This is the typical experience of working as a female painter—instead of looking at the form, he looks at me. I’m more interested in thinking that a bra is a fascist instrument, or that there is no such thing as fake boobs. I like thinking around the body itself rather than using it as a social element to represent women as a whole. I’m thinking about what makes me normalized, what creates violence, but in order to construct the image I’m thinking about the conditions around the body rather than my own experience.

“I’m more interested in thinking that a bra is a fascist instrument, or that there is no such thing as fake boobs”

Your visual style, particularly in your black-and-white paintings, bears some similarity to cartoons and illustration. What appeals to you about this type of graphic stylization, and what are the rewards and challenges of working with it in a fine art context?

Going back to my attraction to the generic, I actually studied illustration as an undergraduate. My day job is in this industry—I’m a freelance illustrator and I work for an animation agency. In that field, I still use my hands and my own sensibility comes through. What matters in that context is efficiency; how efficiently can you communicate with the viewer? I find this fascinating and extremely helpful.

In the fine art context, illustration is often seen as a stylistic treatment. People use phrases like “that’s so illustrative” in a really pejorative context, as if it’s shallow or too literal, but the mechanisms of cartooning or illustration can be quite horrifying when used within the fine art form. They make their subject look digestible or understandable, no matter how awful or unexplainable the thing you’re trying to convey is. The job of illustration is to kill any kind of mystery, because it’s so closely aligned to the language of advertising and consumption.

In some of your recent paintings, tins of Spam feature prominently—the archetypal mass-produced product, which connects to a curious type of hybrid Western-Asian cuisine. What are your intentions with Spam, and how much does your own Korean heritage play into your work?

I was born in Korea, and my parents and brother and I moved to Canada in 2003, when I was twelve. I went to middle school in Canada, and my family are all still there. The first time I used Spam was in a site-specific work I did for NADA in Miami last year. In the most simplistic terms, I wanted to make the Spam seem really out of place in the painting. But at the same time, a tin of Spam is the most direct, recognizable, specific object to viewers. Using it definitely brought an ethnic label to my work. It’s such an American product but it brings a larger political and historical context. It’s this jokey thing but also contains a lot of history.

“Spam is such an American product but it brings a larger political and historical context. It’s this jokey thing but also contains a lot of history”

There is something intensely voyeuristic about your work, as if we have just interrupted an ongoing scene. How deliberate is this heightened sensation of looking, and how do you view your own role within it as creator and observer?

For the longest time I found it hard to grasp the term visual art; art that is only meant for looking; art that is only accessible through looking. Growing up and watching cartoons, the visual experience was never really separated from sound, movement and language. When I work with paintings, I am continually reminded that I am working with a single frame.

I love the sensation of seeing something that you’re not meant to see, that is forbidden; it’s thrilling because that is when I am most aware that I am looking. When I am just going about my day I am just receiving images and visual stimulus: actively and not actively looking at something. I think that is what seeps into this heightened sensation of looking in my work. It’s a hundred percent fictitious, it’s like a little play to me—totally imaginary—and I think that’s the fun of it.

- Demonstration / Illustrations, 2017

- Birthday Wishes, 2017

Violence runs through your painted scenes, often set within domestic spaces or with household objects. What interests you about this particular combination of menace and familiarity?

A lot of the time I use flies, rodents and rats, which I started painting because I kept seeing them in my apartment. I wanted to kill them so much, and I realized how bizarre that is. It’s not even rage, it’s an automatic reflex of wanting to impose violence on them. I was scared to see that in myself—my inner violence—and I’m interested in how depictions of violence become digestible and even attractive just by using the language of mass appeal and stereotypes.

The tropes of the cartoon form—the reasons why it’s kind of horrifying—is that it can reside between harmless, cute, innocent, funny and docile. That is why it’s specific to advertising and children’s books. This style of total powerlessness—and I gravitate towards the power of playing dumb. There is power in that, and you can subvert these somewhat simplistic forms by pointing out the mechanism of them. I don’t think that I’m attracted to shocking depictions of violence; it is the parts that I am able to tolerate that are the most interesting to me.