You couldn’t just go out and find Lee Godie, she had to find you. That’s how one of Lee’s closest friends, Michael Thompson, remembers it. Michael first met Chicago’s most collected artist by chance, when he was fresh to the city as a naïve nineteen-year old in 1968. Lee appeared, dressed in her patchwork fur coat with orange rounds of rouge painted on to her cheeks straight from her watercolour palette. In her best silver screen voice, Lee asked Michael if he wanted to buy a painting, and though Michael was too flustered to adequately reply, that fleeting encounter left a lifelong impression on him. Lee seemed to have that effect on people. “There was some kind of great beauty about her. She was dishevelled, often dirty, and wearing rags—but she wore them incredibly beautifully.”

As it turns out, beauty was important to Lee Godie. The homeless artist considered herself to be Chicago’s home-grown French Impressionist, and was often heard to say, holding court on the steps of the Chicago Art Institute, that her paintings were better than Cezanne’s. With her portfolio (or “muriel” case, as she called it) at her side, and dressed in handmade clothes of layered skirts fashioned from bolt ends and fastened with cameo pins, Lee would stand at one of her regular hangs on Michigan Avenue with a half-unfurled canvas held up under her nose. If she liked the look of you, she would uncurl the canvas more, inviting you to buy, but if something about you rubbed her the wrong way, she would roll up her canvas and gruffly see you off. Her work has an undeniable intensity, and some of it was sufficiently compelling to warrant serious attention, even then.

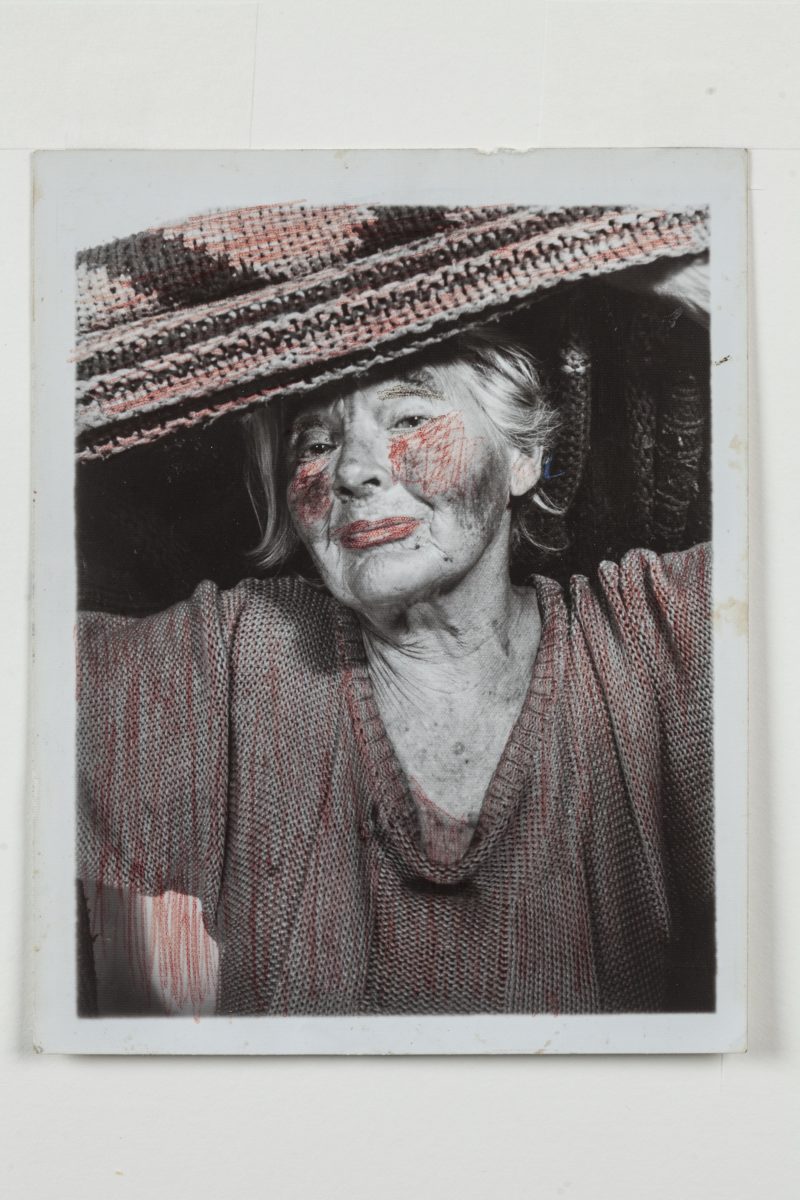

- Both images: Lee Godie, untitled, n.d. Collection of Scott H. Lang, IL.

“Lee appeared, dressed in her patchwork fur coat with orange rounds of rouge painted on to her cheeks straight from her watercolour palette”

Where Lee came from and how she ended up on the streets of Chicago will always partly remain a mystery. She was a very private woman and didn’t offer up personal details easily, or would offer up stories so fantastical they couldn’t possibly be believed. From the facts that I can be sure of, Lee was born in 1908 as Jamot Emily Godee, one of eleven children raised in a middle-class Christian Scientist household. A free and confident girl, she left school after the eighth grade with aspirations to become a singer, but her marriage to steamfitter George Hathaway at the age of twenty-five seems to have frustrated those ambitions.

In 1934, Lee had a son, Sheldon, who died from pneumonia just a year and a half later. Though the couple went on to have two more children (daughters Jamot and Bonnie) some believe that Lee’s husband blamed her, and her Christian Scientist belief in healing through prayer, for the death of their little boy. Whatever the reason, Lee walked out of that marriage, taking four-year old Jamot with her and leaving the baby behind. A few years later, Jamot—who Lee remembered being “as beautiful as Shirley Temple”—died from diphtheria at just six years old.

At this point, Lee seemed to untether herself from her surviving daughter, Bonnie. She went on to marry again in 1948, moving to Tacoma, Washington, where she gave birth to another daughter, but it wasn’t long before she walked out of that family, too, when her youngest was just a baby. Nobody seems to know where she went after that. She just disappeared, resurfacing again some fifteen years later as the beguiling “bag lady artist” of Michigan Avenue.

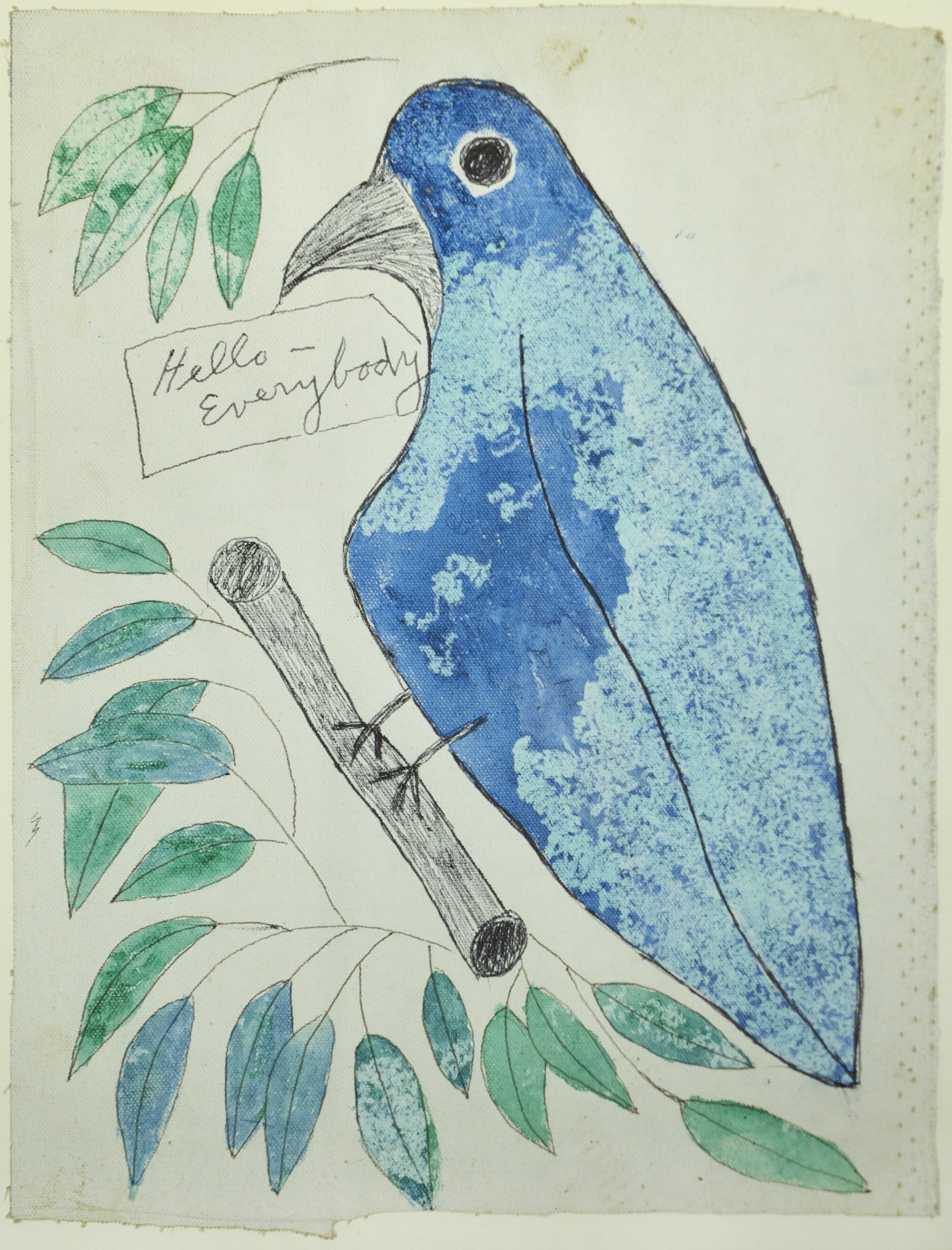

Over the twenty-odd years Lee lived on the street she made thousands of paintings, portraits mostly, but also variations of favourite themes such as birds, hands, leaves and even mushrooms. Her early works are intimate, intense. Glamorous women with huge eyes curtained in impossibly thick eyelashes, rosy-cheeks and red-lips, wearing fancy clothes and fashionable hairstyles or opulent hats. Lee’s women are all beautiful. “I always try to paint beauty, but some people say my paintings aren’t beautiful. Well I have beauty in my mind, but it isn’t always easy to make paintings beautiful.”

With titles like Flaming Youth, Sweet Sixteen, Glamour Girl and Gibbson Girl, it’s clear that Lee’s references were the part-emancipated, hyper-feminine female idols of her youth. She worked from photos in magazines, often choosing Joan Crawford or Princess Margaret as models, careful to alter their likenesses sufficiently so she wouldn’t be sued. She also invited friends, particularly the attractive ones, to sit for her.

Lee had a lot of friends, and even more admirers. She became part of the fabric of the Chicago art scene. People heard about the legend of Lee before they saw her, and an encounter with the artist was always a thrill—one way or the other. It wasn’t enough to buy a work by Lee Godie; people wanted to buy a work from Lee Godie. The transaction was a performance, part of the work itself. In her best moods, Lee put on a show, orating her whimsical musings on life and art in a rising, captivating voice that Michael describes as what a silent movie star might have sounded like with the volume turned up.

“People heard about the legend of Lee before they saw her, and an encounter with the artist was always a thrill”

In her bad moods, she might not acknowledge you, or worse, she might swing at you with her “muriel” case. It’s no surprise Lee had a tough side; life on the streets was hard. She was often beaten up and robbed. During Chicago’s iciest winter nights Lee would check herself into a cheap hotel, though she soon wore out her welcome as she would get paint all over the sheets, try to flush tin cans down the toilet and leave infestations in her wake. She refused to let chambermaids clean her room, and was particularly hostile to those of African American descent.

I learned in writing this article that Lee Godie was racist, which cannot be explained away, excused or ignored; it just has to be known. As someone who prioritised beauty above all else, it’s plain to see that Lee Godie’s understanding of beauty was overwhelmingly white. Her ideas about femininity were based on a white ideal, borrowed from the same movies and magazines on which she modelled her life and work.

Despite being as far from aristocratic as it was possible to be, Lee held herself to her partial understanding of high-society values. The suggestion of a handout would send her into a rage. By many accounts she was actually pretty well-off, selling several works a day for up to $100 a piece. She dressed carefully, draped in scarves and jewellery, and would invite friends to soirees in the park where she would lay on snacks of chocolate or roast chicken, drinking instant iced tea from a silver goblet. In these high times, her conversation was theatrical, almost as if she was performing in character—though the character was always herself.

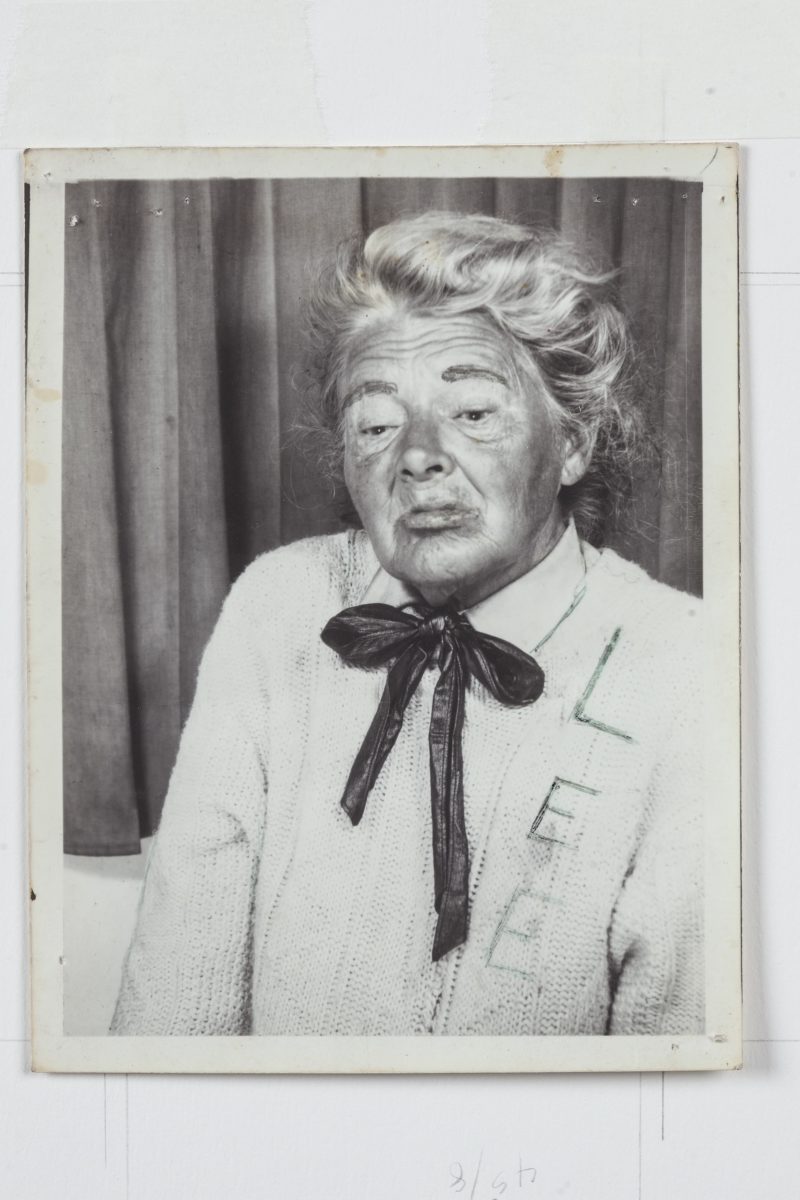

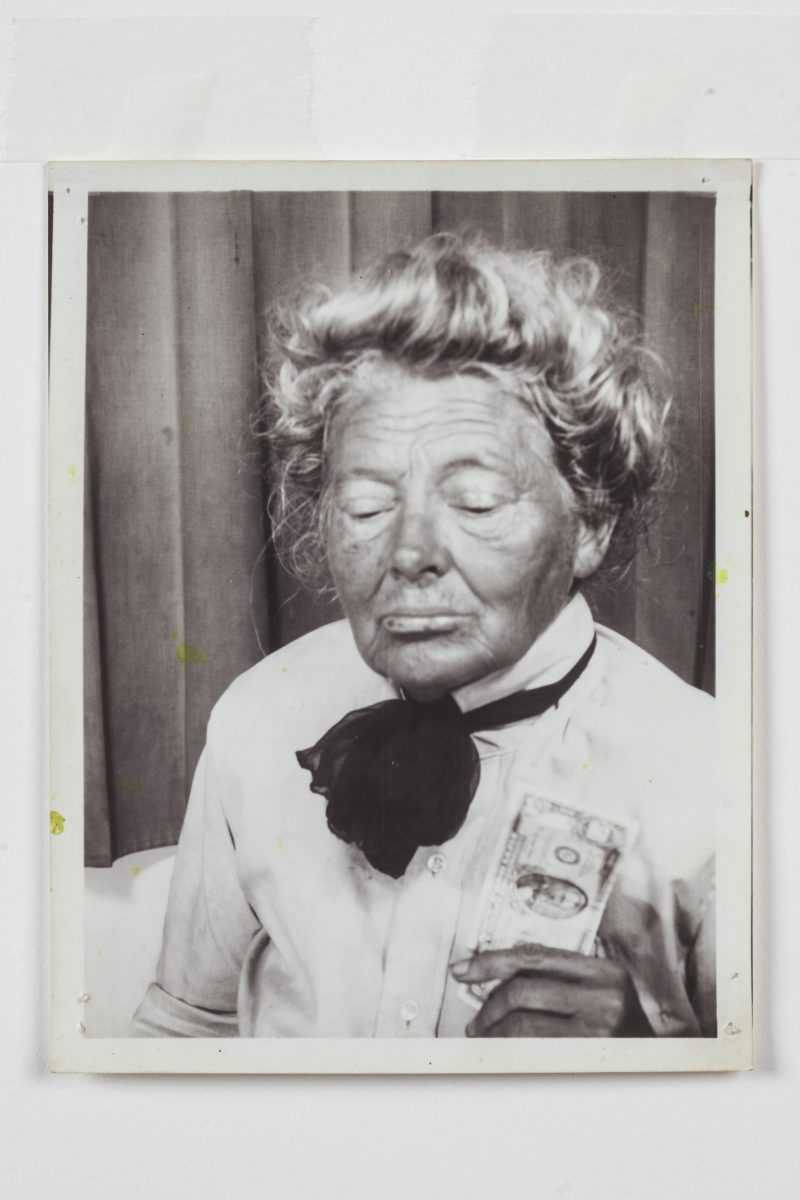

- Both images: Lee Godie, untitled, n.d. Collection of Scott H. Lang, IL.

“There was one place Lee could be guaranteed privacy, if only for a few minutes: the photo booth at the Greyhound bus station downtown”

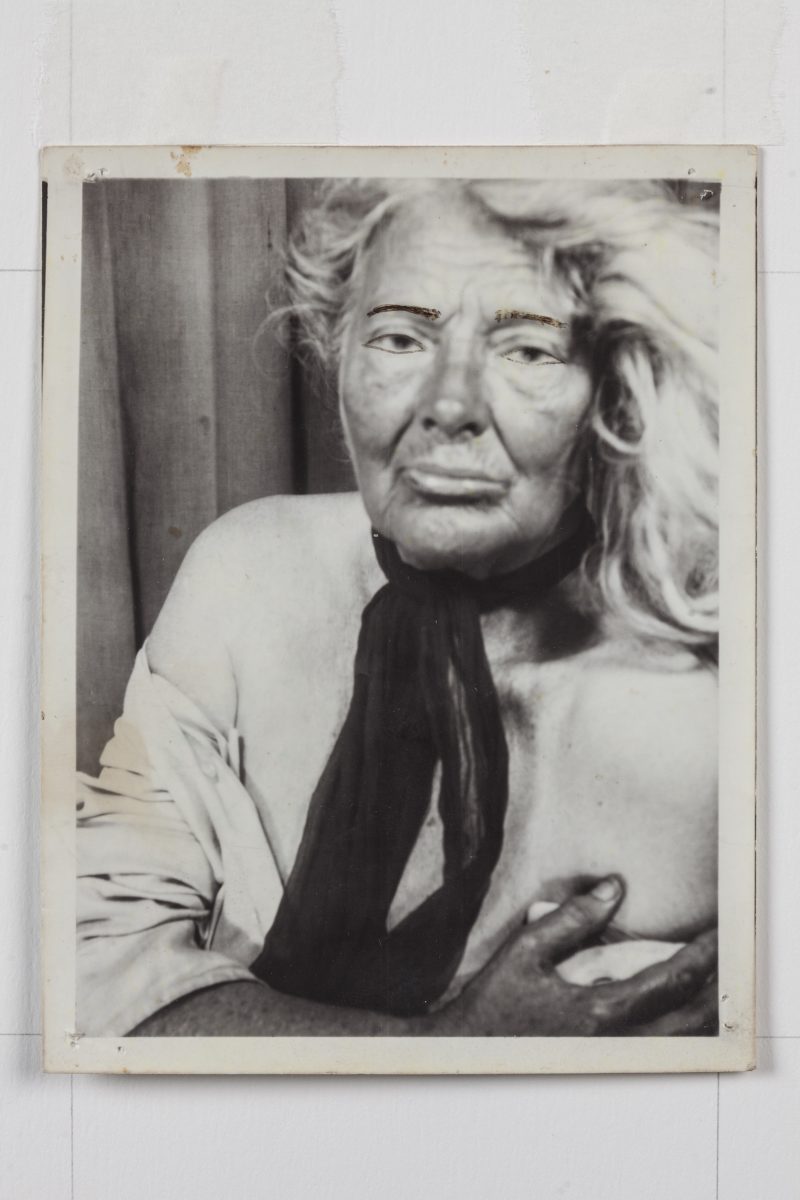

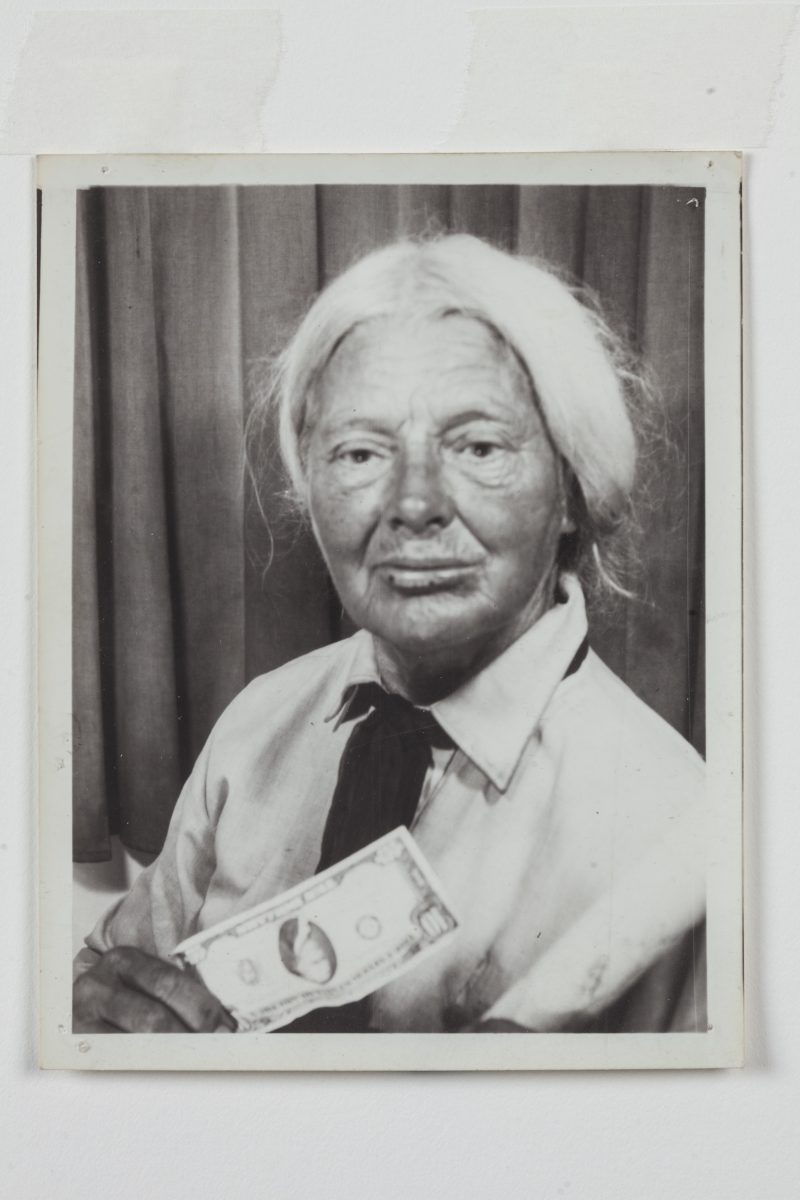

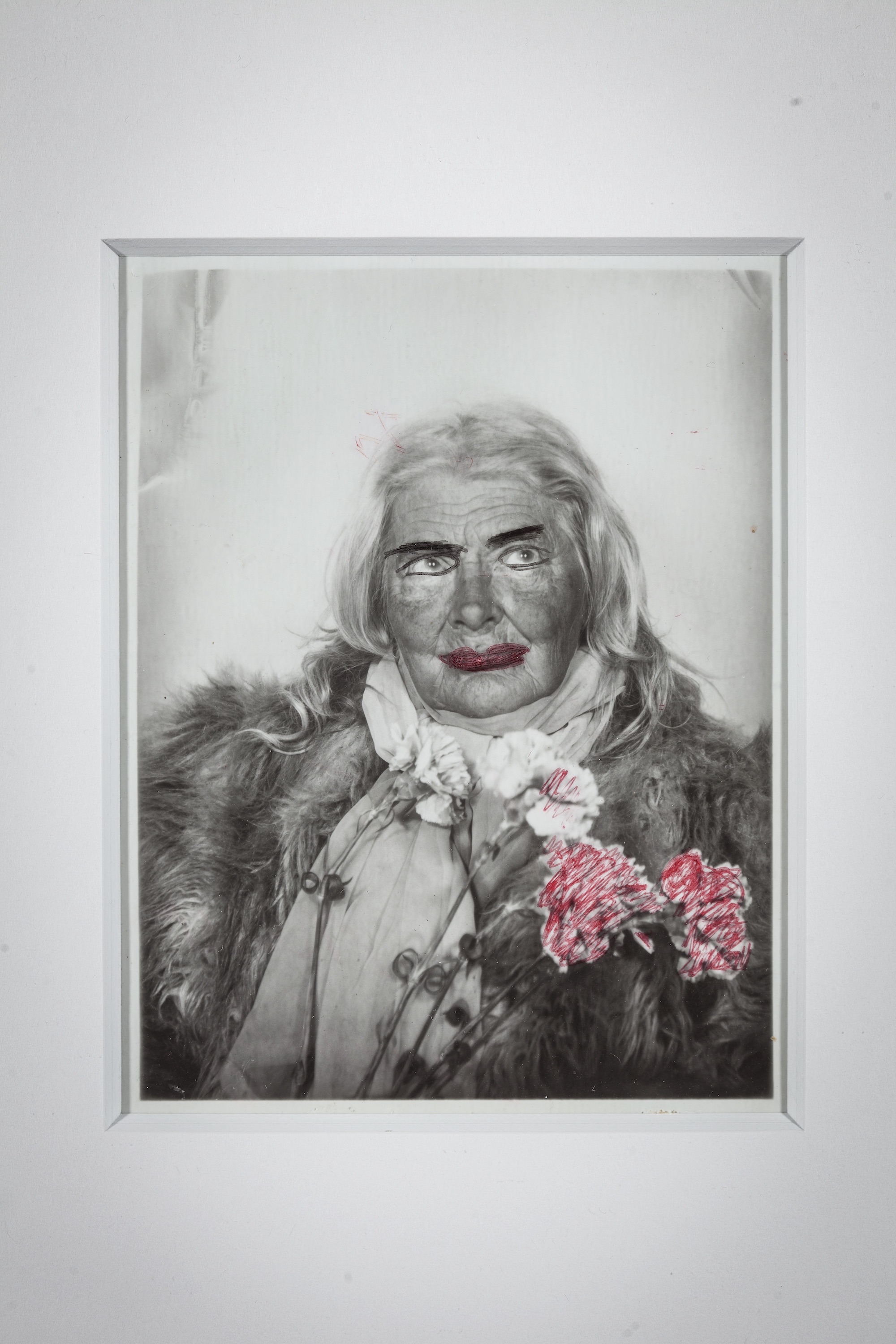

In her life outside, there was one place Lee could be guaranteed privacy, if only for a few minutes: the photo booth at the Greyhound bus station downtown. This was the site of Lee’s most compelling work. Through the use of props, make-up, costume and expression, Lee would transform herself into different iterations of her identity: Lee the shrewd businesswoman, looking down her nose at a fan of $20 bills; Lee the glamour girl, arching her neck alluringly at the viewer; Lee the socialite, dressed for a night on the town with her brilliant silver hair piled high on top of her head. She performed every version of woman going—except “mother” or “wife”, roles that Lee couldn’t bring herself to play in art or life, for reasons only known to herself.

She would alter the 5 x 7 gelatin silver black and white prints with red paint or ball point pen, darkening her eyebrows and eyelashes, adding pink cheeks, red lips or nail polish to emphasise her feminine traits. She inserted text (“The girl who never puts herself to bed…. Lee Godie”), fill in the background with a pleasing colour, enhance her features or obliterate them altogether. Lee would often sew these photographs to her paintings (sometimes using her own hair) as a sort of signature, or give them away as promotions with a sale.

These works anticipate the seminal series Untitled Film Stills 1977–80 by Cindy Sherman—but where Sherman seeks to disrupt an understanding of femininity, Lee Godie embodies femininity in all its haywire multiplicity. Both bodies of work make clear that gender is a performance, that it can be signalled and manipulated using just a few simple devices. The difference is that Sherman is clear that her photographs are not self-portraits, but whether Lee remakes herself in the style of Clara Bow or Katherine Hepburn, the result is always who Lee understands herself to be. The boundary between art and life, representation and reality, just didn’t exist.

Those who knew Lee well held her in the highest esteem, and still speak about her with a hushed reverence. She was courted and collected by major artists of the time, a favourite of the Chicago Imagists, and critics and historians such as Dennis Adrian and Whitney Halstead—one of very few so-called “outsider” artists to receive recognition while still alive. As her reputation grew, so did the media attention, with profiles published in major newspapers in the early eighties. It was the 1985 Wall Street Journal cover feature that put Lee Godie in the national media’s sights, and camera crews arrived from all over the country the next day to hunt down the enigmatic artist. As her friends remember it, Lee handled the onslaught quite well, and why wouldn’t she? To her mind, the attention was only natural.

- Both images: Lee Godie, untitled, n.d. Collection of Scott H. Lang, IL.

“For Lee, the boundary between art and life, representation and reality, just didn’t exist”

It was around this time that Lee’s daughter, Bonnie, went searching for her birth certificate in order to get a passport, and started the search for her real mother. Bonnie finally found Lee in 1988, when she was eighty years old. The baby that Lee had left more than forty-five years earlier was now a middle-aged woman with grown children of her own. Bonnie followed Lee around for months, sometimes seen trailing ten paces behind carrying her things, to the bemusement and suspicion of Lee’s friends. She would draw with Lee in the park, and even spent a night sleeping rough beside her. Eventually Bonnie revealed her identity to her mother. As gallerist Carl Hammer recalls, Bonnie said, “You know I am your daughter, don’t you?” to which Lee replied, ‘Yeah I know who you are, now pick up those bags and let’s get down the street.”

Bonnie remained devoted to her mother, despite the ambivalence. After Lee was hospitalized by a particularly brutal attack in the early nineties, her daughter became her legal guardian, taking care of Lee until her death in 1994. For the funeral, Bonnie made up her mother in fitting tribute. Donned in a grand floppy hat and a fancy dress, just like the ones Lee painted on her women, with circles of orange rouge drawn on her cheeks—Lee appeared to have been plucked out of one of her own paintings.

Whatever else Lee Godie was, she was a woman with undeniable talent, and she was determined to express that talent on her own terms. What might have begun as delusion was eventually made real through white-hot self-belief. Lee lived to be celebrated as the great artist she always knew she was. Her work has appeared in solo and group exhibitions all over the world and is held in permanent collections at the Milwaukee Art Museum, The Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art in her beloved Chicago. Lee’s photographs remain the most arresting of her work, “Have your photo taken when you’re wearing something new, like a new hat, it will make you look special and feel special. There is only one thing wrong with photographs. People can still see you after you’re dead.”