Tombstone Freeway, staged in Camden – at the heart of what artist Claire Barrow calls the ‘graveyard’ of London’s Punk scene – presents an emo phantasmagoria haunted by the ghosts of online subculture. Amidst shredded Laura Ashley wallpaper and Western Ikebana flower arrangements that seem lifted straight from the Beetlejuice (1988) dining-room table, we discuss fear, Scene culture, adolescent self-fashioning and the Whitby Dracula Experience.

Barrow’s previous solo exhibition, Victim of Cosmetics (2023) at Fieldworks, London, was a meditation on the viscous anxiety and dopamine-driven pleasure of being a consumer participant in an all-pervasive beauty industry pushed by algorithms. Tombstone Freeway, currently on view at The Koppel Project, is underpinned by a comparable feeling of horror mixed up with joy; while Barrow approaches the commodification of alternative identities with a critical streak, she refuses to condemn the impulse to anchor the self in protean combinations of clothing, images and media, no matter how transitory or manufactured the impetus for doing so may be.

Before reorienting her creative approach towards visual art, Barrow garnered critical and commercial acclaim as a designer; she made her London Fashion Week debut in 2012 as part of Fashion East, the same year she graduated from the Fashion program at the University of Westminster. Though her design vocabulary – hand-painted leather, hallucinatory line drawings employed as textile prints and a rapacious appetite for historical references – was always entangled with art-making, Barrow remarks upon the pitfalls and benefits of bridging the perceived gap between the two industries. She describes weathering fears about the validity of her position within the art world: as an artist with a background in fashion, as a Northerner, and as someone without an art school pedigree. Nonetheless, for Barrow, the creative flexibility afforded by opting out of the brutal cycle of ‘churning out’ collections every six months is worth these concerns: of her practice, she says, ‘I like to kind of reinvent it every time; my medium will be dictated by the kind of concepts I’m addressing…so having that freedom now to use different mediums and change the systems that I’m working within has been a really freeing thing – and kind of changed my life.’

As her move toward self-defining as an artist gained traction, Barrow held solo exhibitions at Dinner Party Gallery, London (Pipe 2021), The New St Ives School (The Birth of Another Individual, 2020) and Soft Opening’s space in Piccadilly Circus (Pig Latin Library, 2018). Each of these revolved around paintings and spray-paint sketches, which merge a saccharine faux-naivety with something darker – mutant fairytale creatures, the strangeness of a lucid dream. The sculptures at the centre of Victim of Cosmetics retain some of the language of these earlier works, calcified and thickened into glutinous pastel monoliths that resemble mirror reflections gone rogue, coated in the innards of mashed-up makeup bags.

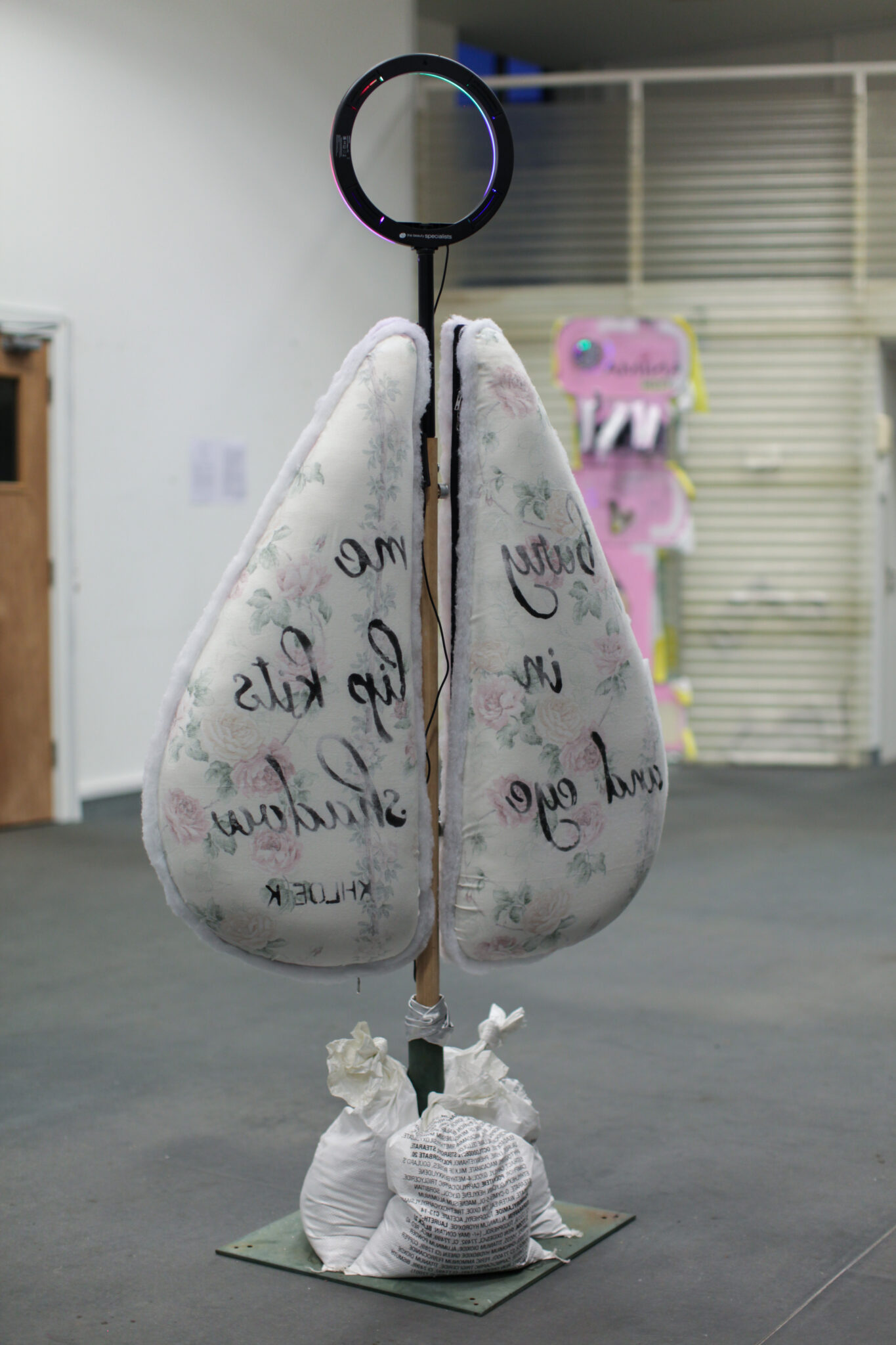

At The Koppel Project, Barrow returns to the concrete, found fabric and wadding that gave these earlier, more abstract sculptures such bodily heft, this time using them to articulate humanoid forms. Medusa (2024) reclines in a parody of the pose favoured by painted courtesans; her mottled grey form is regaled in plastic pearls, polyester satin and a synthetic purple up-do, a Halloween-shop Miss Havisham. In Whitby Gothic (2024), Barrow sets doll eyes and a pierced tongue within a hand-cast silicon mask; she tells me, ‘I wanted to create this Gothic sculpture…Gothic to me is the damsel in distress, the preyed upon woman in the novel.’

The work’s name references the Goth Weekend that takes place each year in Whitby, not far from where Barrow grew up; she cites the Whitby Dracula Experience as an inspiration for the ‘scare-ride waiting room’ feeling of Tombstone Freeway. The experience is a walk-through of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, with references to the Francis Ford Coppola film and the appearance of Whitby in the novel, featuring mangled dummies, plastic gravestones and a baroque approach to LED lighting. Barrow describes going around the experience with her phone torch on to get a better view of ‘the dirt on the floor’, the constituent parts of each spooky vignette – ‘there’s a woman in a coffin, and it’s just a mannequin with a wig on and this blue light on her’ – the places where the seams of the experience’s construction show. There’s a sense of revelry in the kitsch as an opportunity for real fears to be rehearsed through theatricality, exaggeration and humour, compounded by the audio piece that emanates from Whitby Gothic’s mouth and Medusa’s rectum, in which an AI voice reads a script created from a list of crowd-sourced fears, anonymously submitted through her website.

This confessional outpouring of fears into an online platform is an encapsulation of what the internet has always been, but the moment singled out by Barrow is that of 2000s ‘scene’ culture – of MySpace, emo bands, Blingee artworks and a public-facing emotional vulnerability paired with protective hair and clothing. Chris, Luke, Alex (2024) presents a ghoulish reimagining of Chris Dakota, who Barrow describes as being a ‘historical figure at this point,’ infamous for his ‘spiky hair…kind of like a weapon’ and illustrious MySpace profile. Barrow, a self-professed ‘MySpace addict’ as a teenager, describes it as a place for early conversations around mental health, saying ‘you would share content that was maybe dark, about feeling like an outsider in school, and you’d finally find a tribe of people that you could connect with.’

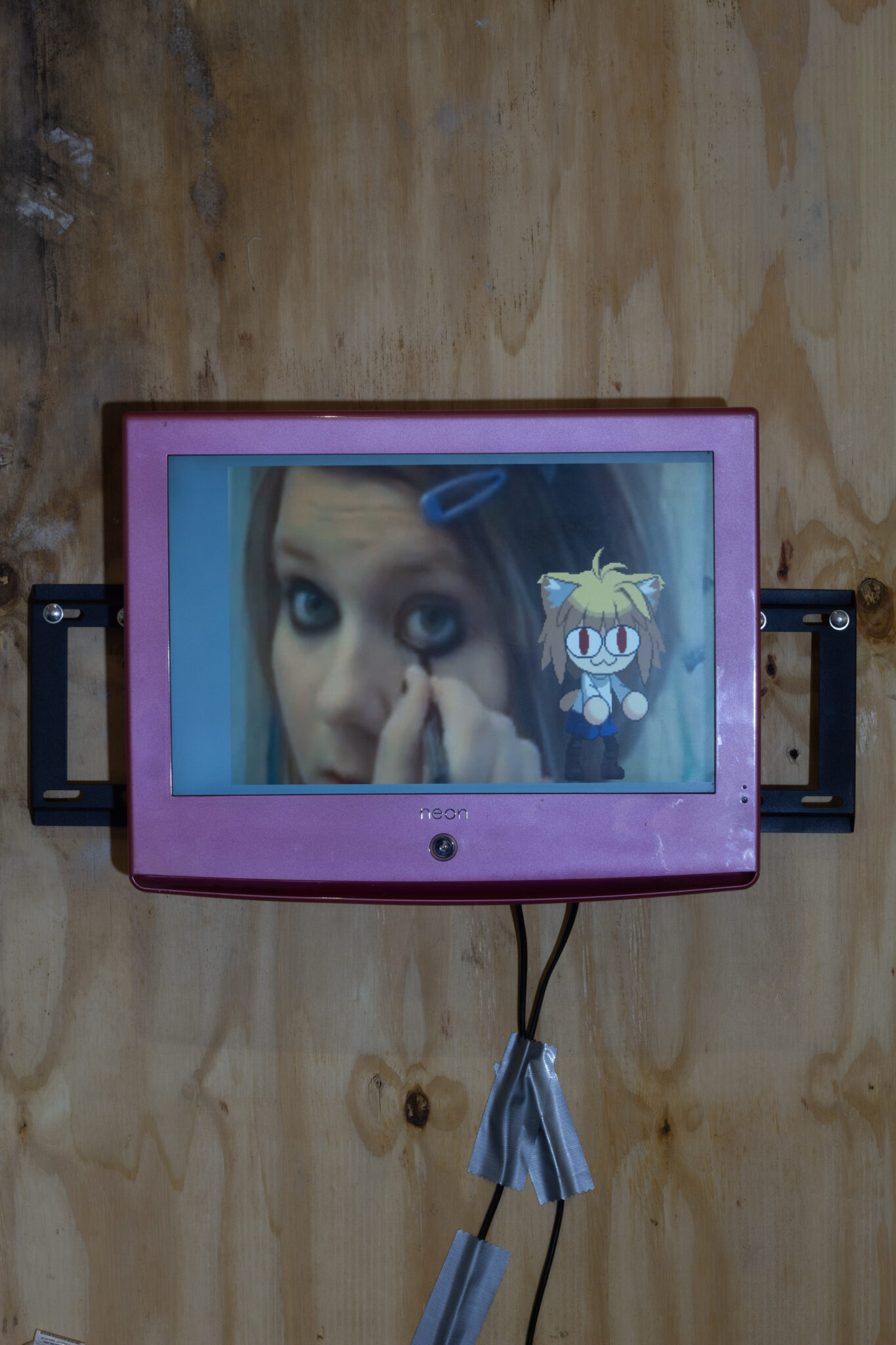

A specially commissioned video work by archivist and documentarian Daisy Davidson (behind the Instagram account @hysteric.fashion), A Visual History of Online Subculture & Cursed Images (2023) provides some contextual background for this moment through a series of found photographs. Featuring anime girls, boxy desktop computers, grainy eye-makeup tutorials beneath side-swept fringes and amateur photo shoots set in graveyards, teenage bedrooms, and spaces resembling malls or convention centres, the visual essay acts as a taxonomy of signifiers linked by a specific visual sensibility that is remarkable in its dislocation from any discernible sense of place.

Notable in this taxonomy is the recurrence of branded products and mascots: Demonia platforms; Hello Kitty speakers and Kuromi shoes from the Sanrio family; Nintendo’s Kirby; Nokia mobiles and Monster energy drinks. It feels like a truism to state that the imperative to digitally share a self-constituted through phasic allegiances to a particular range of products or aesthetics is now naturalised and unavoidable. What Davidson and Barrow capture is a moment that feels suspended between the de-localised, widespread accessibility and dissemination of subcultural signifiers and a time where these signifiers were attached to a definable community. Barrow summarises this transitional phase adroitly: ‘I’m not saying subculture doesn’t exist anymore, but that was the last true subculture that was invented and the first one that happened on the internet.’ In her observation that ‘every subculture merges now; I feel like subculture has taken on a new [status] where it’s still a means to connect, but it’s an aesthetic thing above all else,’ it is tempting to search for a note of pessimism, but this would erase the nuance and generosity in Barrow’s embrace of cultural bricolage.

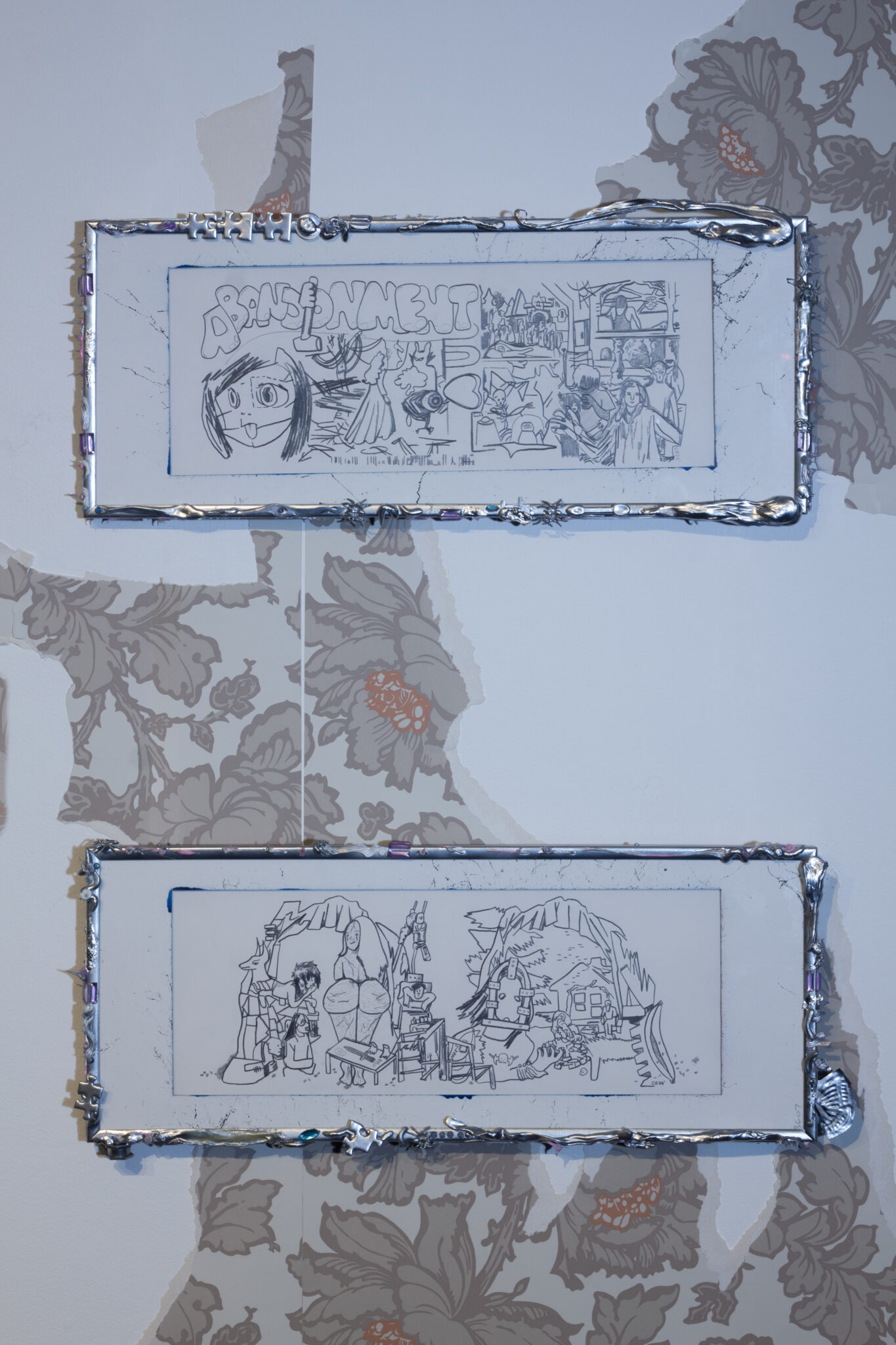

Referencing back to her Victim of Cosmetics show, she notes that ‘I was addressing the consumerism of beauty and the marketing techniques and packaging of that industry – but as a consumer and contributor of it – and I’m doing the same thing here.’ The ten drawings that feature in Tombstone Freeway are set in frames that look like molten silver jewellery; they are made up of collaged objects Barrow has found or kept over the years, including ear stretchers she no longer wears. Poised at the point of transformation between ornament and weapon, comprised of artefacts delineating facets of identities past and present, the drawings act as a materialisation of Barrow’s creative ability to evolve and acquire versions of herself without leaving the old ones behind. ‘I was very ‘scene’ at the time, and then I really embraced the punk scene and the hardcore scene… So yeah, remixing all these different references together is a big part of who I am and the fashion I used to make. So I’m just continuing on from that, but self-assessing along the way, I guess, about the state of things right now.’

Written by Sybilla Griffin